Remembering Chris Burden: ‘Testing the limits of everything,’ friends say

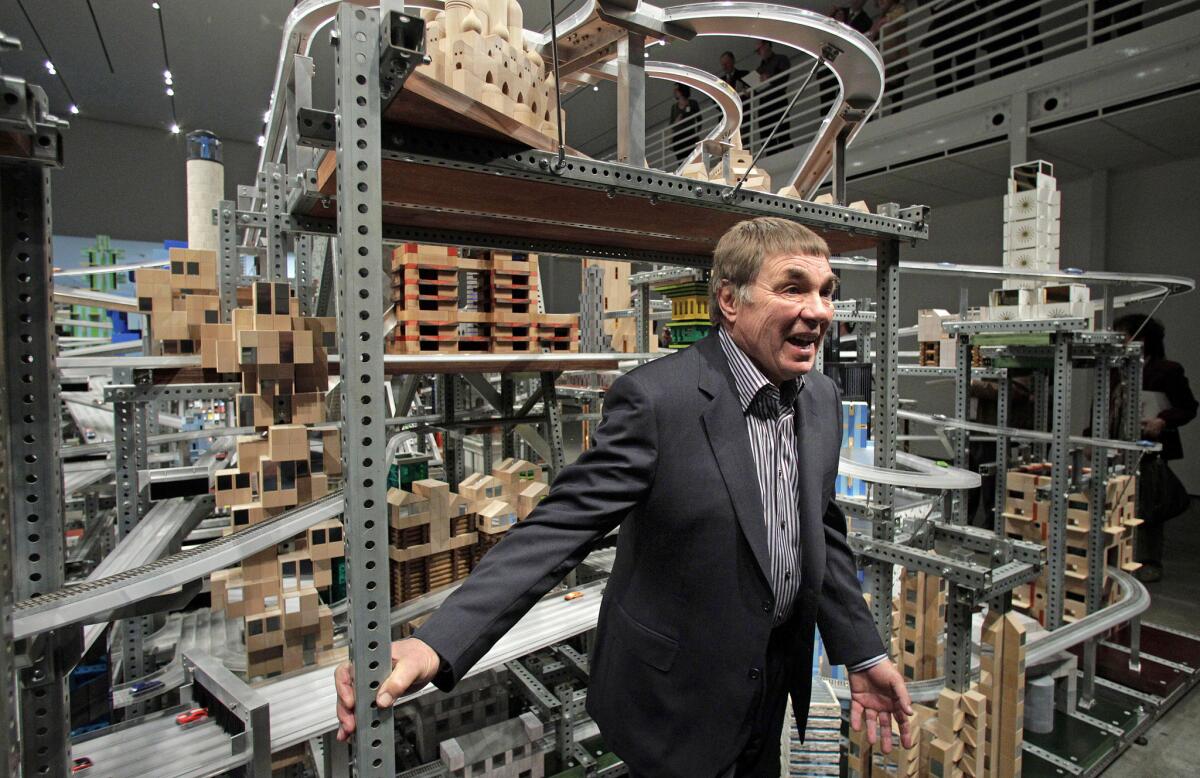

In this 2012 photo, Chris Burden stands in front of his kinetic sculpture “Metropolis II” at the

Chris Burden’s dear friend, the painter Ed Moses, called Burden “the most magnificent person to ever appear in California as what we call an ‘artist.’”

On Monday, a day after Burden died in his Topanga Canyon home from cancer, Moses and others who knew and admired the artist recalled what made him one of L.A.’s greats, first in performance art and later in sculpture.

Burden’s friends cited the artist’s drive to challenge his own mortality through his art, including an early performance work in which he had himself shot in the arm and another in which he remained in a school locker for days on end. Moses recalled one performance in which Burden strung himself upside down, naked, with a rope around his ankles.

“People thought he was nuts and some art critics put him down for doing these pieces,” Moses said. “But he was a real magical man.”

Burden didn’t just challenge himself in art, Moses said. He did the same in everyday life. At Burden’s Topanga Canyon compound, Moses once found Burden with his hand gnawed by a coyote. Coyotes had tracked and cornered one of Burden’s dogs.

“Chris didn’t like that, so he grabbed one of them one day and held it down with his hand and tried to stuff sand in the coyote’s mouth, and the coyote got loose and bit his hand really bad,” Moses said.

Burden’s unpredictable passions and imagination made him the kind of artist that he was, said friends including Ed Ruscha.

“Chris was always a wild hair of an artist. He occupied an outermost spot in the universe and we envied him for it,” Ruscha wrote in an email.

Another friend, painter Billy Al Bengston, called Burden “a force, but a force that I didn’t understand.

“His aesthetic was so far removed from mine. His art was all about reference to the world, mine is all about reference to myself.”

Burden proved his integrity as an artist and demanded respect from his peers, Bengston said.

Artist Charles Christopher Hill attended UC Irvine with Burden in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Hill occasionally filmed or photographed Burden while he performed. Hill said he once kicked Burden down the concrete steps at the Art Basel show.

“There were a lot of onlookers -- it was a featured item of the day,” Hill said. “But I never heard any feedback. We just did it, and at the end of the day that was it.”

And that’s pretty much how things went in Burden’s early years, Hill said. He would perform, and sometimes nobody would be there. One of Burden’s performances consisted of him lying for hours on a shelf.

“He did a piece at Robert Irwin’s studio in Venice and you’d go in and say, ‘Hey, what are you doing?’ And no one was there, but he’d be up on a shelf,” Hill said. “A lot of it was well documented but not well attended.”

It was Hill’s impression that Burden planned his work to maximize the possibility of publicity -- or rather, to perpetuate his notoriety. Though much of his work appeared to be dangerous, Hill said, he thought Burden was careful not get too hurt.

His creativity was boundless, said photographer Judy Fiskin, who attended Pomona College with Burden.

“He was irreplaceable. He had an imagination that was like no other artist of his generation,” she wrote in an email. “So many of his pieces were both witty and scary, designed to destroy the decorum of the museum, and in the case of Samson (my favorite), the museum building itself.”

Fiskin wrote that she saw and heard the Big Wheel (a performance sculpture featuring a three-ton, cast-iron flywheel eight feet in diameter and powered by a motorcycle) in action a few times and its noise and speed thrilled and frightened her.

“I remember once at MOCA that when the roaring of the engine started, virtually everyone who was in the museum came from the other galleries to see it, and stayed for a long time, watching,” she recalled. “It always made me feel that it was on the verge of launching the wheel into the onlookers, and some small part of me always wanted to see it. Even the tiny cars in Metropolis II at LACMA are menacing, once you know they’re going 240 mph.”

Los Angeles artist Catherine Opie recalled Burden’s impact at UCLA, where she teaches and where Burden was on the art faculty from 1978 to 2005. Opie said that one of Burden’s key contributions to training young artists was launching a program at UCLA called New Genres that focused on performance art, video and other less traditional art forms at a time when they had yet to join the mainstream.

“He inspired students to stretch the definition of what art-making was. He allowed them a sense of freedom,” Opie said. “There’s a huge generation of people out there who were completely influenced by Chris.”

Opie said one of her favorite encounters with Burden’s art came at the Tate Modern museum in London, where he had set up a combination sculpture and machine that was supposed to fold paper airplanes, then launch them into an adjoining gallery.

It wasn’t working, but Opie carries with her the memory of seeing “engineers in lab coats, with clipboards, trying to make this thing work” -- and how that captured Burden’s love of mixing art and technology and attempting things that weren’t guaranteed to succeed. “He was one of those artists that you really wanted to see what he was going to make next.”

Jennifer Bolande took over from Burden as head of the New Genres program after he retired in 2005.

“He kind of redesigned the way we understand video and performance art and the way they interact,” Bolande said, adding: “Everything he did had far-reaching implications, a sociopolitical critique, and he was constantly testing the limits of everything. Visiting his studio was always an event. These engineering and technological feats taking place in there were sort of beyond belief, and heroic in a way. ”

Burden also had a playful and humorous streak, said Bolande, who was scrounging on Monday to find a photograph of him smiling so she could post it on the New Genres website. “There are hardly any,” she said, “but he was just really funny.”

Burden kept news of his illness to a close circle, but a number of his friends said Monday they knew that Burden’s wife, Nancy Rubins, had discovered advanced melanoma on the back of his head while cutting his hair.

“It didn’t make its pain known,” Moses said.

Ann Philbin, director of the Hammer Museum in Westwood, summed up the feelings of many when she wrote via email: “Chris was pure, brilliant, and uncompromising -- the quintessential rebel. He was an L.A. treasure and I can’t believe we have just lost another one.”

Times staff writer Deborah Vankin contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.