Review: A shipshape ‘Billy Budd’ caps Britten 100/LA

A bellicose anti-war opera, Benjamin Britten’s “Billy Budd” is a stifling shipboard drama with only strong male voices, a theater of testosterone. Manhood stands trial. In 1951, the year of its premiere, “Billy Budd” bravely evoked homoeroticism on the British lyric stage when homosexuality was outlawed. Britten further bravely insinuated disapproval of the military code when his country was recovering from World War II.

Praise comes easily to “Billy Budd.” It is consummate music theater. Britten makes the oppressive lyrical and ambiguity accessible. Sophisticated musical structure and sophisticated subject matter, especially for the time, do not violate the mainstream, even middlebrow, needs of grand opera. Do not be afraid of “Billy Budd.”

Obviously some have been. When Los Angeles Opera mounted “Billy Budd” in 2000, that was the first major L.A. production of the opera. Saturday night, the production finally returned to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion as the culmination of the “Britten 100/LA” festival, last year having been the centenary of the composer’s birth.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

This has been a strong season for L.A. Opera, and “Billy Budd” continues the trend. Liam Bonner’s engaging Billy is a standout. A lot of other guys are on stage — 20 named characters, plus a chorus of sailors and boys — and all come through. James Conlon, the force behind L.A.’s Britten celebrations, conducts with unerring conviction.

At least the director and the designer are women. Francesca Zambello’s production, with sets and costumes by Alison Chitty, was originally created for the Royal Opera and Paris Opera nearly two decades ago. When it was first seen here, The Times was bombarded with letters (all from men) of outrage at the directorial license of the production and for stylizing a late 18th century British warship not accommodating the ship’s hierarchy.

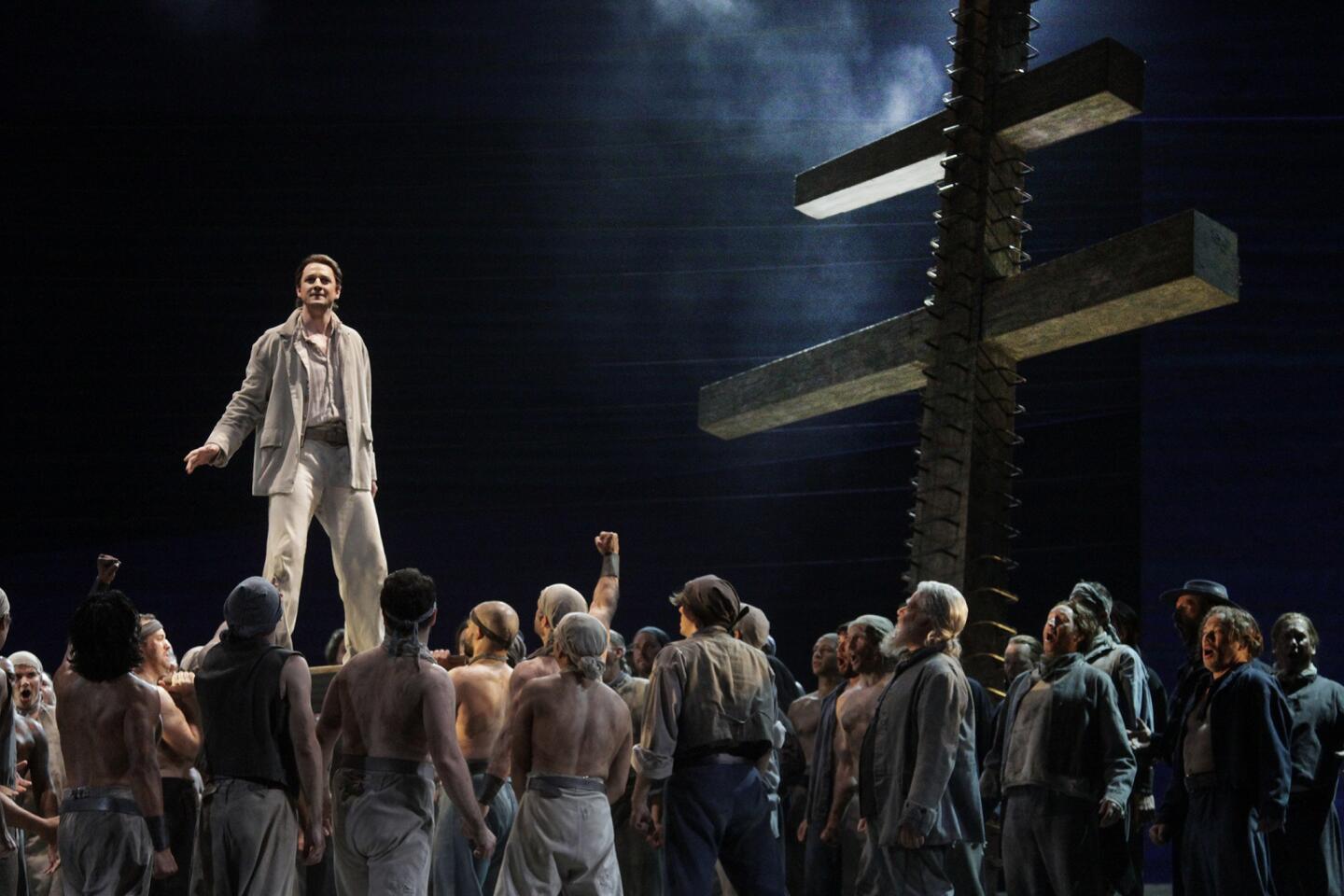

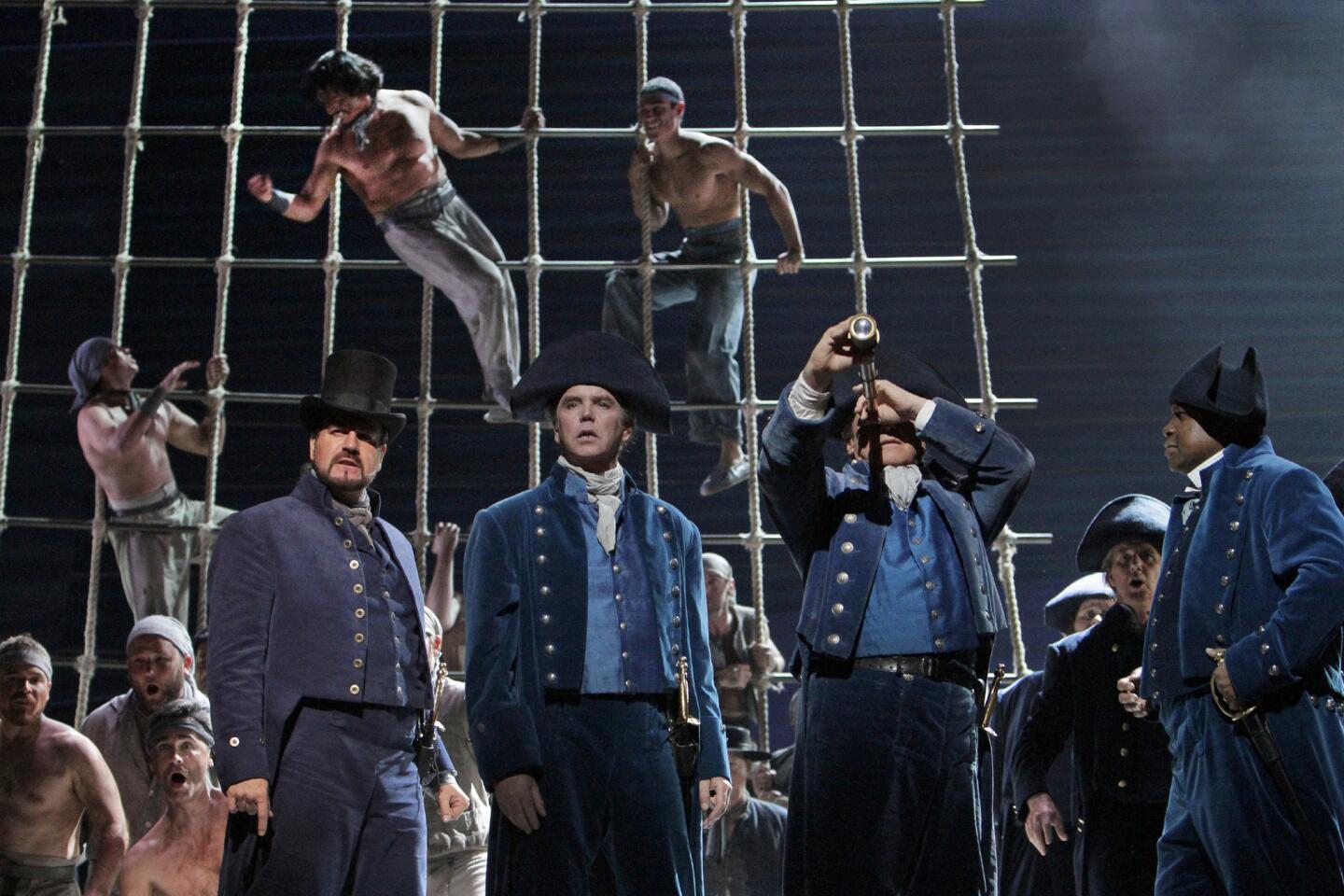

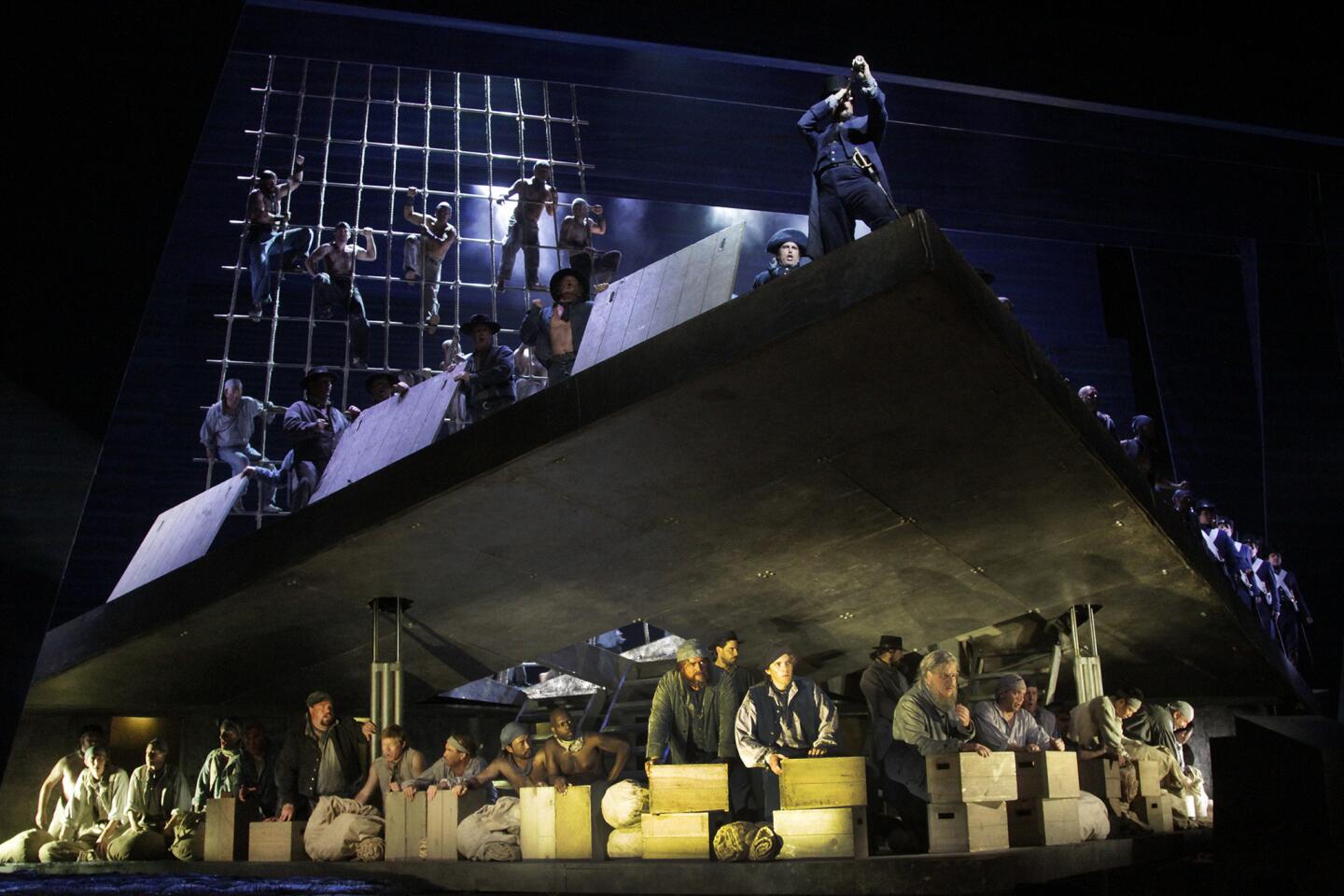

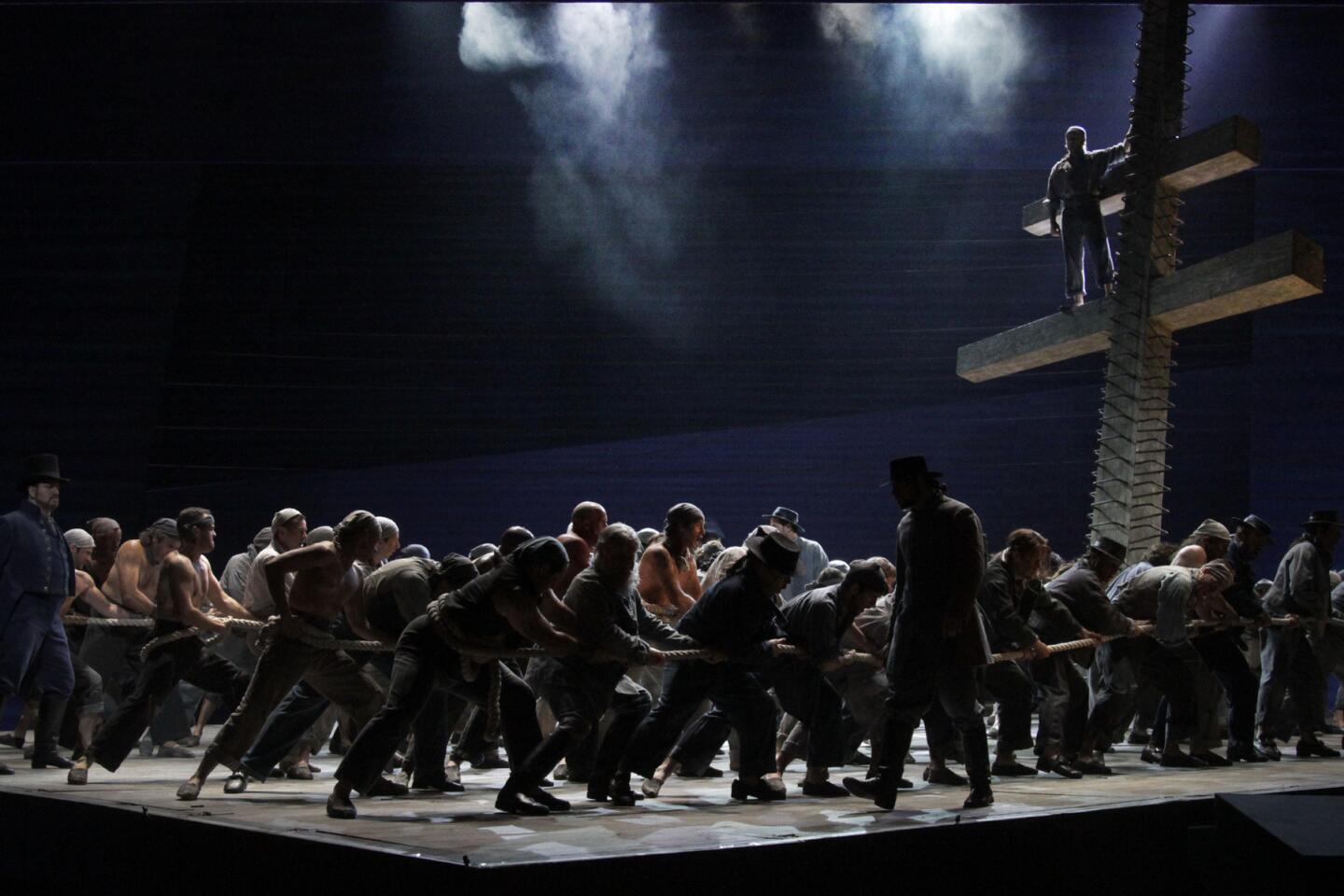

Although Zambello has brought a feminist point of view to some of her other productions, here she mainly let the opera speak for itself. Compared with the directorial license common and expected these days, her “Billy Budd” is in fact straightforward. The set is a bare platform jutting out at an angle as the ship’s deck, which rises to reveal quarters below. There are various trap doors, a mast and rigging, but little else. The staging (now directed by Julia Pevzner) focuses entirely on the sailors, letting boys be boys and giving them enough rope to hang themselves.

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

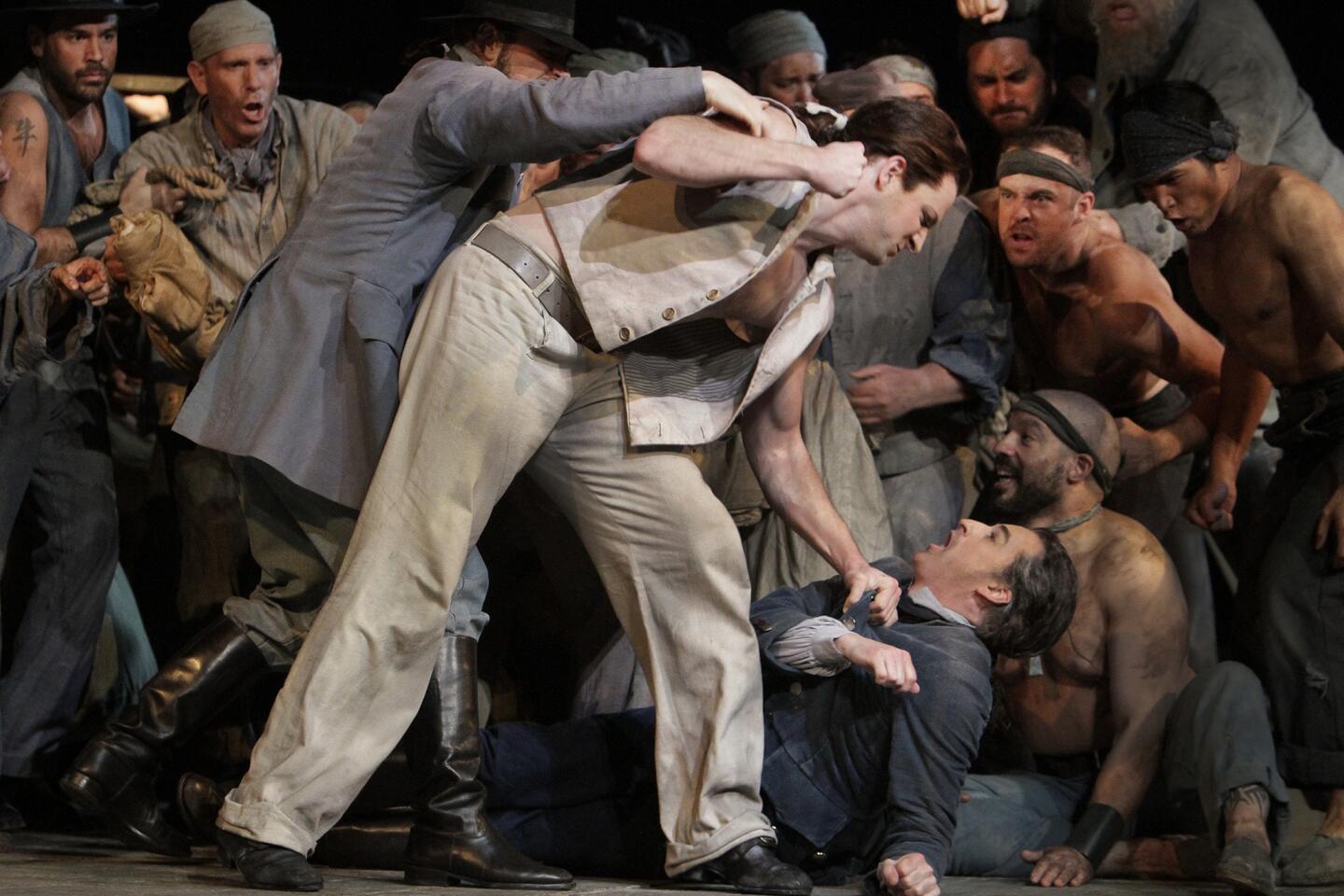

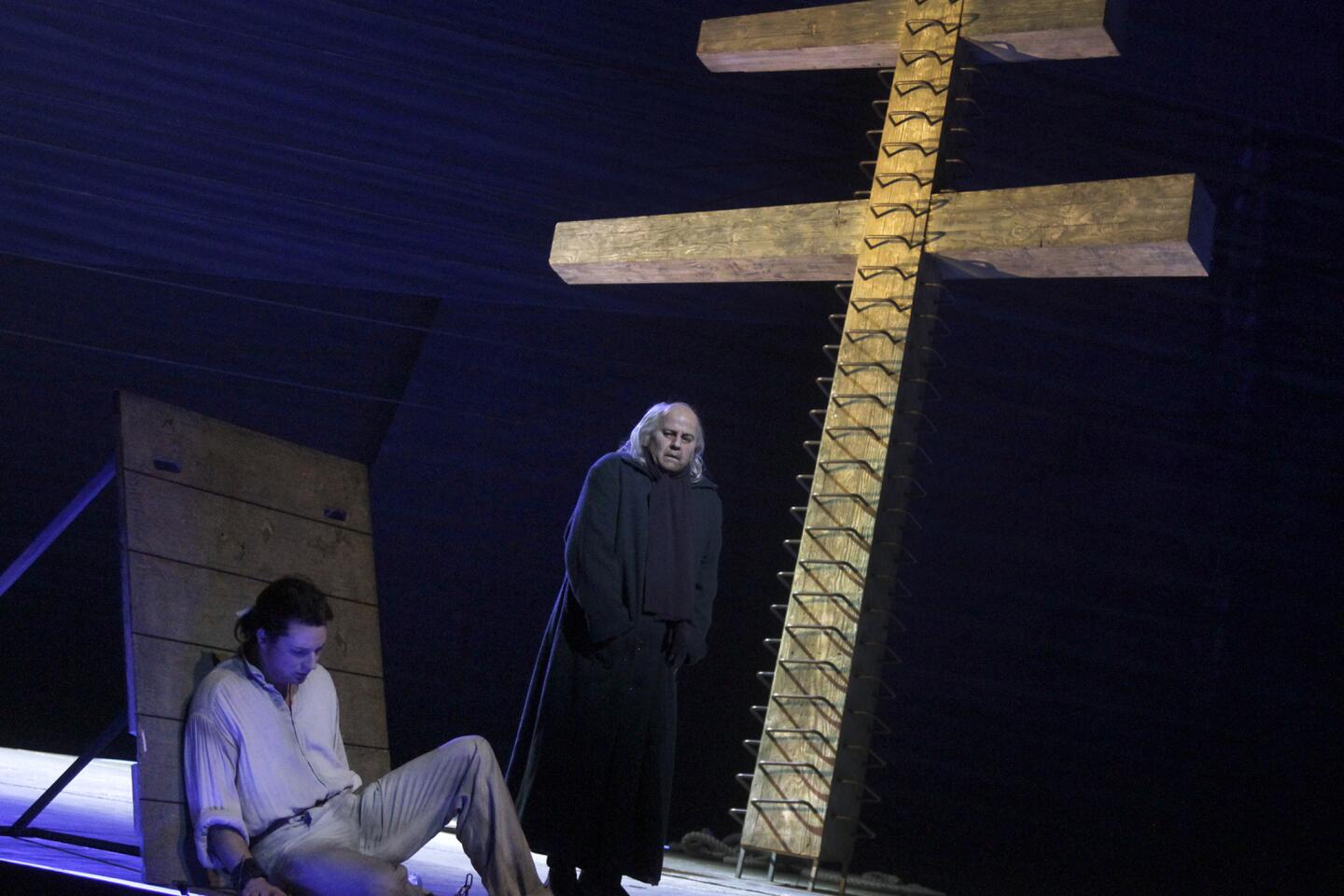

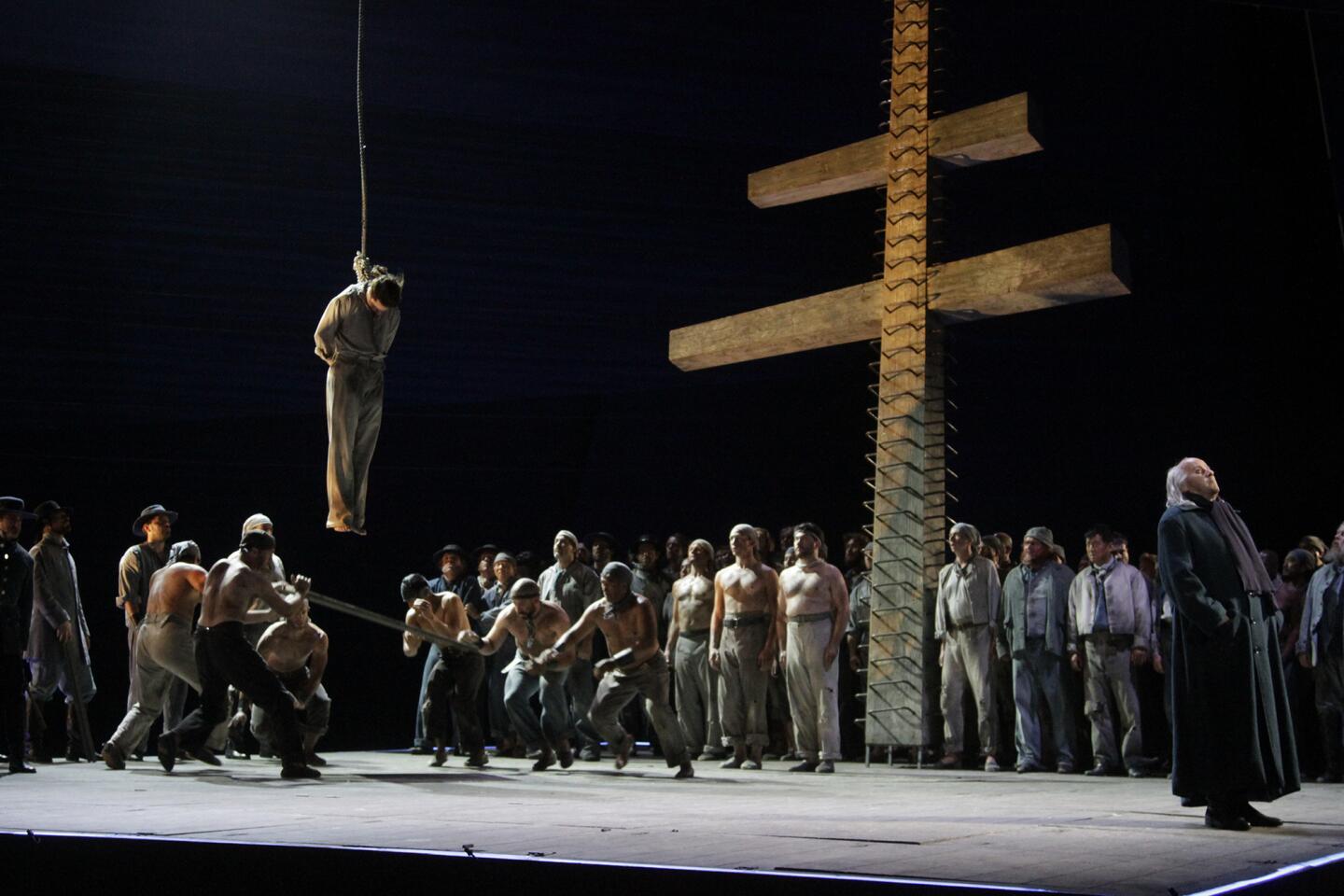

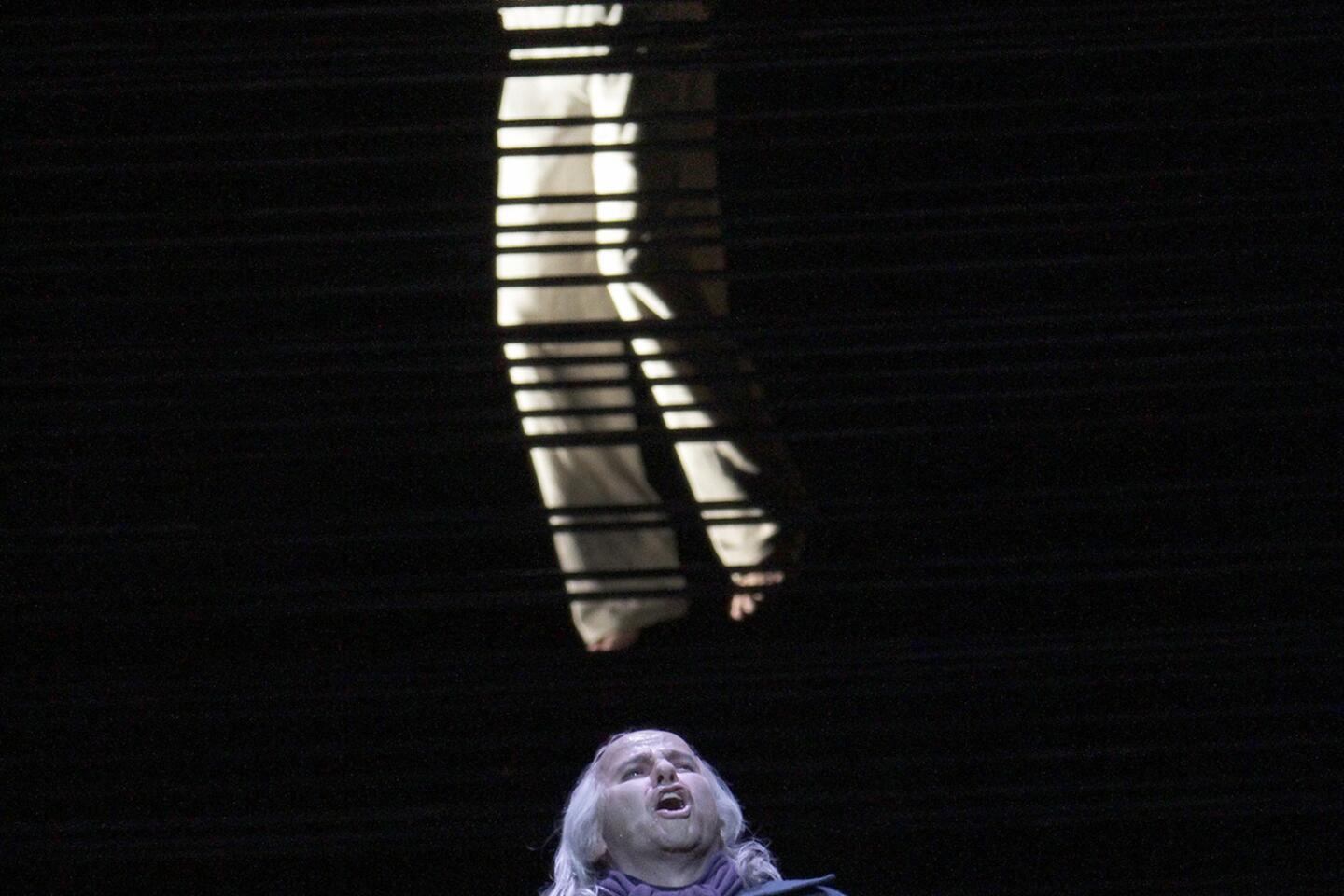

The opera follows Melville’s late novella closely. In a prologue and epilogue, Captain Vere is haunted after allowing Billy to be executed, as the law, literally interpreted, required. Billy’s beauty and charisma makes him the target of the master-at-arms, John Claggart, who desires Billy. Instead, he frames Billy, killing what he can’t have. When falsely charged with fomenting mutiny, Billy, who stammers, is unable to speak and, in frustration, strikes his accuser and accidentally kills him.

“Billy Budd” takes its strength from the claustrophobia, not of the ship but of operatic tradition. Claggart is Iago all over again, and Britten’s model here is Verdi’s “Otello.” Billy is Christ-like, and Chitty’s mast has the quality of a cross.

For an opera about moral and sexual ambiguity, everything is spelled out. A spooky composer with a talent for creating auras, Britten finds an unerring orchestral color or a chord or an evocative phrase for everyone and everything. From the very opening, in the orchestra, you can practically smell the salt air of the sea, sense that something will go terribly wrong and feel the unease of Vere’s ethical vacillations. And so it goes. Britten’s suggestiveness, even his apt musical expression of ambiguity, tells you exactly what to think and how to feel.

Still, the drama is ever immediate, and L.A. Opera missed few tricks. This was Bonner’s first Billy, but the baritone takes to it with an aw-shucks ease, more American than British, more Melville than E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier (Britten’s librettists). Tenor Richard Croft’s Vere is manly in ways that aren’t always the case but should be. Greer Grimsley’s Claggart parades nastiness in voice and manner.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

Among the ship’s curious personalities are Greg Fedderly’s Red Whiskers, James Creswell’s Dansker and Anthony Michaels-Moore’s deferential Mr. Redburn. But Britten is as accomplished in creating a sense of larger purpose in ensemble numbers as he is in creating dramatic interaction, and those weird big choruses of heaving sailors or reminiscences of sea shanties could be even more moving than soliloquies Saturday.

But really, it’s the orchestra. This is where Britten makes the theater happen, it is where he grabs you by the lapels, where he is his most brilliant, and, if you don’t like being manipulated, his most insidious.

There were times when I simply wanted to push that big band away. But that was me. Let it also serve as a strong compliment to Conlon, who emphasizes clarity, directness, strong color, mood and everything else needed to make the performance work and, love it or not, hard to ignore.

--------------------------------------

‘Billy Budd’

Who: Los Angeles Opera

Where: Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles

When: 2 p.m Sunday and March 16; 8 p.m. March 5, 8 and 13

Running time: 2 hours, 55 minutes

Cost: $19 to $306

Info: (213) 972-8001 or https://www.laopera.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.