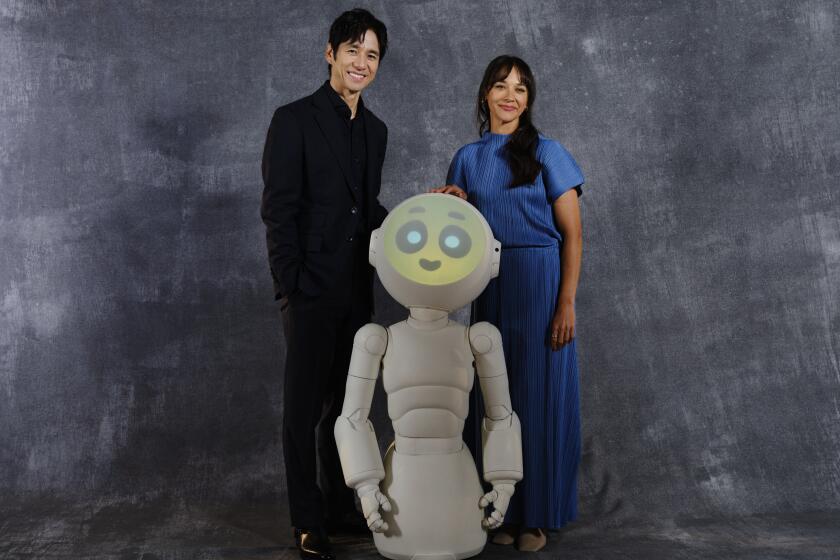

‘Sunny,’ led by a powerful Rashida Jones, is best when focused on personal relationships

In “Sunny,” premiering Wednesday on Apple TV+, Rashida Jones plays Suzie Sakamoto, an American living in a near-future Kyoto who has apparently lost her Japanese husband and 8-year-old son in the crash of a commercial airliner — although the possibility that things might be otherwise is raised early in the season. As in most mysteries, much is not as it seems.

Grieving and refusing to publicly grieve, Suzie finds herself the unwilling recipient of Sunny (Joanna Sotomura) an Apple-white domestic robot whose adorable, Sanrio-style expressions display on a video screen. This is, she’s told, supposed to make her feel less lonely. (“I’m a hugger,” says Sunny, much to Suzie’s horror. “Bring it in.”) She has no actual friends.

It’s at this point that Suzie learns that Masa (Hidetoshi Nishijima, “Drive My Car”), her husband, was not a refrigerator engineer, as she believed across their decade-long relationship, but was an important person in cutting-edge robotics; he had personally programmed Sunny for Suzie out of, I can only suppose, some prescient apprehension of his eventual absence. Nothing else makes sense, anyway.

(I’m going to call Sunny “she,” because the robot reads as female — in Colin O’Sullivan’s original novel, “The Dark Manual,” since re-titled to match the series, it’s called Sonny — and because all the other main characters, including the primary antagonist, are women. It’s their world we’re in, not accidentally.)

Her initial attempts to divest herself of Sunny entwine with her desire to learn just who her husband was; there will be skulking and unpleasant if incomplete discoveries. Drowning her sorrows in the bar where she and Masa were regulars, Suzie meets lively, motley haired Mixxy (Annie the Clumsy), a new bartender, who tells her of the Dark Manual, an illegal underground guide to homebot hacking that might allow her to turn Suzie completely off rather than just unreliably put her to sleep.

It has apparently less benign applications, as well, and every step leads her further into the coils of an overly complicated plot; dangerous situations follow upon dangerous situations, with Suzie and Sunny operating as bickering, bantering buddy cops and Mixxy tagging along out of interest — or is it self-interest? We also see early on that Suzie is under surveillance — by whom? For what? Yakuza are eventually knitted into the story, which is, frankly, a bit of a disappointment; even exotic organized crime is, ultimately, mundane.

It’s easy to resist Sunny at first, because Suzie does, and especially as it’s impossible to tell whether she might cause her owner harm. There is a suggestion in the series’ opening that homebots can go dangerously haywire, and Suzie remains suspicious of Sunny even as she comes slowly to accept and rely on her. But one warms to the robot eventually and, indeed, my main concern through the season was whether it would treat her well.

The Apple TV+ series ‘Sunny,’ premiering Wednesday, highlights questions about the humanity of robots and artificial intelligence.

Like animals, in a drama or social media video, sentient machines excite our sympathies. As soon as you give a robot a face or a voice, or even a vocabulary of beeps, clicks and whirs, they become indistinguishable emotionally from human characters, no matter how many times someone will assert, “It’s just a machine.” If anything, they’re more sympathetic for not being us. Astro Boy. Data. C-3P0. Replicants. The death of HAL 9000 is the one heartbreaking moment in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” With her big eyes and soft voice, her attitudes of hope and worry, her capacity to dream and to get “drunk” on visual feedback loops, Sunny is as much a protagonist as Suzie. (The series is named for her, after all.)

Among a smorgasbord of secrets, it’s suggested that Suzie also is hiding something — she won’t answer when Masa, in a long flashback to their meeting, asks her “the real reason” she moved to Japan. Her desire to disappear introduces the real-world concept of hikikomori, an extreme form of social avoidance in which people sequester in their room, sometimes for years — Masa having been one. (“It’s not a meditation retreat,” he says, when Suzie expresses interest. “When people looked at me, it hurt.”)

Some plot points feel mechanical, like a Rube Goldberg gadget where the interaction of a boiling tea kettle, a bursting balloon, a scared cat and a falling bowling ball are all required in order to, say, ring a bell — when the logical thing is just to take a stick and strike it; there is a lot of extra energy expended in getting from A to B — I won’t say “wasted,” but there’s a degree of nonsense you’ll need to accept.

The series, created by Katie Robbins, is much more successful when it concentrates on personal relationships — I’m including Sunny here, obviously — than on the mystery and conspiracy elements, which are no more compelling or even the point of the journey than a villain’s plans in your average Bond movie. Human mysteries are always more interesting. The prickly relationship between Suzie and her prickly, passive-aggressive mother-in-law, Noriko (actor, singer, woodcut artist Judy Ongg, quite wonderful) is intentionally frustrating and beautifully played.

There are detours in the home stretch, which leads to a twist or a cliffhanger, depending on whether a second season is coming. (There certainly seems more to discuss.) An antepenultimate episode — following the now-common strategy among streaming serials of backing up into the past before finishing in the present — gives Nishijima’s Masa a welcome wealth of screen time; the episode that follows goes, surreally, inside Sunny’s head, for more backstory and context, while Jones remains almost entirely offscreen.

Wayward plotting aside, it’s easy to watch — very nicely made, handsomely designed and photographed, with colorful minor characters and striking performances by the major ones. Best known for “The Office,” “Parks and Recreation” and “Angie Tribeca,” Jones — though she spends much of the time depressed — is powerful even in her inwardness. There’s not a lot of vanity in her performance and less comedy than usual. (The series has a certain comic lightness, from the bright Saul Bass-style opening credits onward, but it is rarely funny.)

Finally, she’ll become a sort of slow-moving action hero — think of Doris Day in the climax of “The Man Who Knew Too Much.” The creators may have.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.