How ‘Painkiller’ turned legal disclaimers into moving tributes to opioid victims

The legal disclaimers that often appear in TV shows inspired by real events tend to use the same dull, boilerplate language to notify viewers about the license the series has taken with historical fact. These carefully vetted caveats exist to prevent costly lawsuits and public backlash. They are rarely memorable — much less capable of making viewers weep.

But “Painkiller,” a Netflix limited series about the opioid epidemic and the people caught up in it, turns this staid convention on its head. Each of the drama’s six episodes opens with a formulaic statement: “This program is based on real events. However, certain characters, names, incidents, location and dialogue have been fictionalized for dramatic purposes.”

Rather than showing up as an easily ignored onscreen caption, the disclaimers are read by the bereaved parents of young people who died as a result of OxyContin addiction. The parents appear on camera, clutching photos of their son or daughter. Once they dutifully recite the pro-forma legalese about the show’s fictionalized elements, the parents pivot to talking about what isn’t fiction: the beloved child whose once-promising life was cut short by opioids.

Episode 1 opens with Jennifer Trejo-Adams, who wears a T-shirt bearing the name of her son, Christopher Trejo, and a blurry photo of his face. Her eyes cast downward and clearly scanning a script, she dispassionately reads the disclaimer. Then she pauses, exhales deliberately, and looks directly at the camera before continuing: “What wasn’t fictionalized is that my son, at the age of 15, was prescribed OxyContin.”

Holding a picture of a beaming Christopher playing baseball as a teenager, she recalls how he battled addiction for years, and died at 32 — “all alone in the freezing cold in a gas station parking lot. And we miss him,” she says, wiping away tears with a manicured hand.

OxyContin is a dying business in America.

Created by Micah Fitzerman-Blue and Noah Harpster, the multipronged drama stars Matthew Broderick as Richard Sackler, the Purdue Pharma executive and family scion who played a key role in developing and marketing OxyContin, a powerful narcotic, to the American public. He is the most prominent real-life figure portrayed in the series, which also follows fictional characters who stand in for actual players in the crisis, including Uzo Aduba as Edie Flowers, a U.S. attorney investigating the drug’s terrifying spread across the country; Taylor Kitsch as Glen Kryger, a tire shop owner who becomes hooked on painkillers after a workplace accident; and West Duchovny as Shannon Schaeffer, a recent college graduate recruited to peddle OxyContin for Purdue.

“Painkiller” is based on two acclaimed journalistic accounts of the opioid epidemic — the 2003 book “Pain Killer: A ‘Wonder’ Drug’s Trail of Addiction and Death“ by Barry Meier, one of the earliest exposés on the subject, and “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain,” a New Yorker article about the Sackler dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe. Though the series is a necessarily fictionalized retelling of events that relies on imagined conversations and composite characters, it is, broadly speaking, a true story, one that accurately captures a vast American tragedy that continues to unfold. Studies by the National Institutes of Health have shown that prescription opioid addiction can lead to illicit drug addiction. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, in 2021, 71,000 Americans died from overdosestied to synthetic opioids. The problem has grown especially acute in L.A. County, where fentanyl deaths surged more than 1200% from 2016 to 2021.

The idea for the testimonials came to director and executive producer Peter Berg during a videoconference with lawyers at Netflix, who told the “Painkiller” creative team they needed to include a disclaimer — something you might expect in a series that deals with an extraordinarily wealthy and once-influential family, the Sacklers, who’ve been tied up in billion-dollar lawsuits and complex bankruptcy proceedings for years.

“It didn’t sit particularly well with me,” recalled the filmmaker (“Deepwater Horizon,” “Patriots Day”), who has experience with stories about tragic real events in recent American history. “So I asked whether it would be an option to have parents whose children who had died because of OxyContin reading that disclaimer, and then saying, ‘What is not fiction is that my child died of an OxyContin overdose.’”

The original disclaimer “felt like we were letting them off the hook, like we were giving them the ammunition that made it very easy to say, ‘Hey, this is all made up,’” said executive producer Eric Newman, in a separate interview. “Netflix legal was very supportive of our efforts to find some way to mitigate that.”

Now, instead of than undermining the message of the series, the disclaimers-cum-testimonials in fact make it more compelling, said Newman: “A lot of the things that we do [in ‘Painkiller] have a legitimacy that they might not have had if we just warned viewers ‘what you’re about to see is not entirely true.’”

Berg thought it was apt — perhaps even cathartic — for the survivors to deploy the kind of carefully vetted jargon that is more typically used to protect powerful corporate interests for their own cause. “You could feel [that] these folks were fed up with lawyers and legal speak,” he said. “So when they were able to say, no, forget about the lawyers, forget about the settlements — what is real is my son died at 18. My daughter died at 23. You could tell that every one of them was extremely passionate, emotional and angry still.”

Through Berg’s documentary production company, Film 45, the filmmakers began searching for people in Southern California with loved ones who died as a result of opioid addiction.

It was easy — heartbreakingly so — to find people who fit the bill.

“We had at least 80 [families] instantly that all wanted to tell their stories,” said Berg. “That was something that just reinforced the grotesque nature of this epidemic.”

“I wish I could say that we had to search far and wide for people who lost a child to opioid addiction, but unfortunately, it was really easy,” said Newman, who interviewed the families and directed the disclaimer sequences. (Like millions of Americans, Newman also has a personal connection to the subject matter: his stepbrother died recently from an overdose following a long fight with addiction. “By the time it killed him, it had already taken everything from him,” he said.)

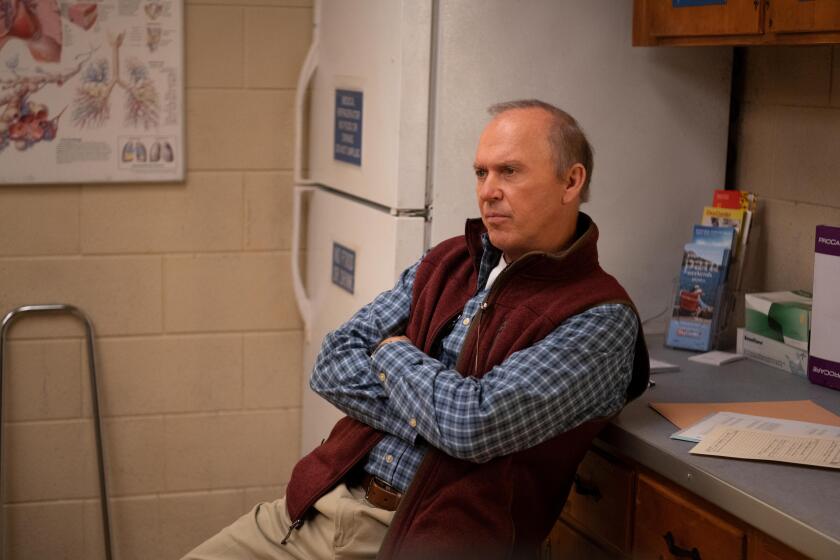

A ‘Spotlight’ for the opioid crisis, starring Michael Keaton as a small-town doctor ensnared in the epidemic, ‘Dopesick’ is schematic but effective.

Because there were so many families affected by the epidemic in a relatively concentrated geographical area, Newman was able to film all the testimonials in two emotionally and physically exhausting days. “I was driving from place to place with this incredible respect and gratitude for people who were able to have something like this happen to them and somehow endure,” he said. While the crew was setting up the camera and lights, he would often start by talking to the surviving family members about their loved one, asking what they were like and whether they appeared in their dreams. (They all did.)

It was often hard for the parents to reduce their child’s story to a few sentences, so Newman offered some guidance. “My direction to them was that this is what you want people to know about your child and less about the people who did this to him,” he said. The goal was to convey the humanity of the individuals and reject the stigma, which portrays addiction as a moral failing (an idea that was promoted by Richard Sackler, who once described people addicted to OxyContin as “reckless criminals” and wrote an email in 2001 suggesting that Purdue should “hammer on the abusers in every way possible” in response to growing concerns about the drug).

“I also told them how I felt about the disclaimer, and that it was perfectly OK to read it with an eye roll if they wanted,” added Newman. “They have all, unfortunately, become activists in this battle. And I think they saw this as an opportunity to get this message even further out there.”

Trejo-Adams, who lives in La Crescenta, was eager to share the story of her son, Christopher.

“We need to share our stories so that maybe someone else won’t be ashamed of theirs,” she wrote in an email. “I’m not ashamed of my son. What happened to him wasn’t his choice. It wasn’t his fault ... or mine [now if someone could just tell my heart that].”

Trejo-Adams also said she was also motivated by a desire to fight the stigma associated with addiction. “People walk around in judgment every day, looking down at every addict and homeless person that they see. They look down at them like they are trash. I know because that’s how they looked at my child. My hope is that after watching ‘Painkiller,’ maybe they will look at them a little differently.”

Episode 6 features Rodger and Kim Ward, whose son, Riley, was also prescribed OxyContin, and died at 28. “He tried his hardest to get right and get straight again and get sober and he just couldn’t do it,” says Rodger in the scene, holding a framed picture of a smiling Riley. “He was a wonderful kid. He had the biggest heart you ever saw, and our lives will never be the same.” As Rodger breaks down in tears, Kim lovingly rubs his shoulder.

The Wards, who live in Lake Forest, were equally keen to participate in the series. In an email to The Times, they recalled their son Riley as an athlete who rarely drank or did drugs until he broke his back riding an ATV in the desert. He underwent spinal surgery and was prescribed OxyContin, but his dosage crept ever upward.

“His medication wasn’t helping after a while so they kept upping his dosage,” they wrote. “We trusted the doctors and the fact they said it was not addictive. The rest is a long sad story — arrests, incarceration — and ended with his death.”

After struggling through cycles of shock, anger, guilt and disbelief, the Wards eventually found a grief support group filled with parents like them, where they came to understand “that it could happen to anyone, anywhere,” they said. “We both found that the one thing we could do to help our own grief was to help others cope with it,” particularly by sharing their family’s painful journey. “It hurts every time we talk about the worst thing that could ever happen, but it helps us deal with the never-ending grief and we believe [know] it helps others.”

The Wards believe that “Painkiller” will help viewers understand the damage caused by corporate greed and see that “addiction is a disease like any other disease,” they wrote. “We hope that the stigma attached to this can be removed and that money will be spent where it belongs — in education and treatment.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.