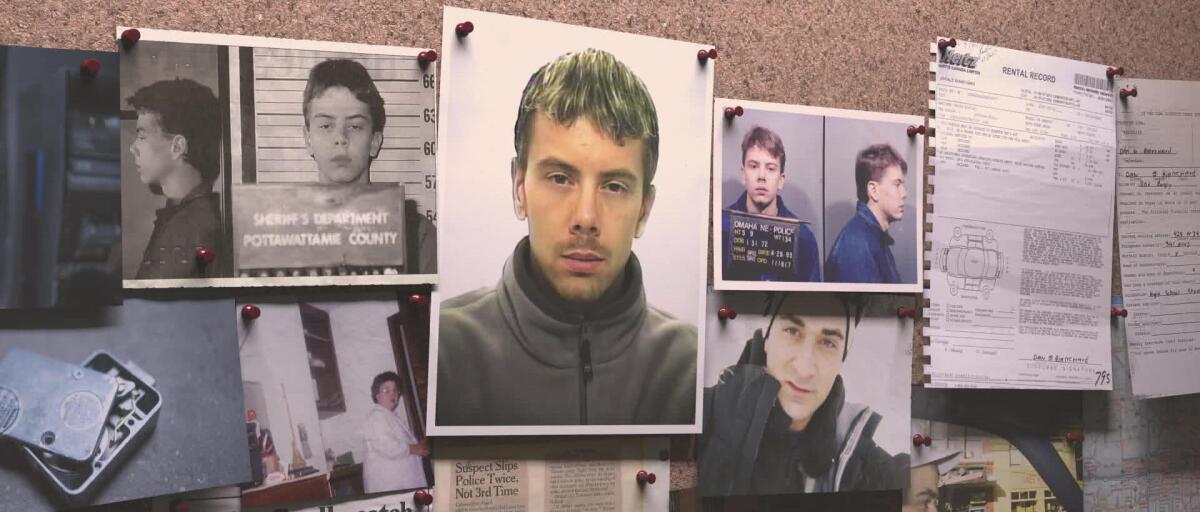

‘The Jewel Thief’ is a close look at serial criminal Gerald Blanchard

As a Canadian-born teenager growing up in Omaha, Neb., Gerald Blanchard reveled in shoplifting and petty thievery with his friends, capturing the high jinks on video. He quickly graduated to more ambitious crimes, and getting arrested did nothing to alter his belief that he was a criminal mastermind who was smarter than everyone around him.

During the ’90s and aughts, Blanchard made that stand up — his meticulous and ingenious planning enabled him to slide past security systems, stealing sums as large as $500,000 from ATMs and banks across Canada and, allegedly, to swipe the diamond-and-pearl Star of Empress Sisi from a secure case inside Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace.

Blanchard’s story, now recounted in Landon Van Soest’s documentary on Hulu, “The Jewel Thief,” is a wild ride. (Warning: Spoilers ahead!) He escapes from the authorities once by hiding in the ductwork at a police station and another time by stealing a police car while still in handcuffs; he falls in with crime syndicates and arms dealers; and, in varying versions, he pulls off the extraordinary Sisi Star heist by parachuting out of a plane or scaling a roof.

He is ultimately caught by two relentless police officers in Winnipeg, Manitoba, thanks in part to a mistake that can only be called blatantly careless and stupid.

TV critic and true-crime buff Lorraine Ali selects the 50 best true-crime documentaries you can stream on Netflix, HBO Max, Hulu, Prime Video and more.

“I’ve been obsessed with the story for a decade,” Van Soest says in a video interview. “I grew fascinated by the layers of his character. He can be kind and polite, but we’re dealing with a criminal with a lot of antisocial behavior. As far as I know, no one was ever hurt in his crimes, but he clearly has a dark side.”

In the film, Blanchard — who styled himself as a Moriarty-like supervillain toying with the cops — offers a small, tight smile at best and often turns cold. But now, seeking to rehab his image and in his own video interview, Blanchard stakes out a noble Robin Hood role for himself, saying he participated in the documentary because “I want people to see I’m not just a common thief that robbed from people.”

“I targeted institutions because when I was a child, banks took away our house,” he adds. “Some people don’t trust me, thinking I’d steal from them, but I’m totally against stealing from [individual people]. I also wanted people to see my nicer side and how I donated money to charities.”

But Blanchard’s answers don’t always add up. Though he speaks about never robbing or harming individuals, when I asked about a petty robbery arrest that came after his prison time for his more heralded crimes, he relates a convoluted story that involves helping a friend break into a car to steal $4,000 worth of goods, allegedly in lieu of money owed.

When I note that he speaks on camera about his willingness to hurt anyone who has betrayed him, he defends his retribution policy. “My mind-set is if I’m being intimidated or hurt or pushed into the corner, I’m going to fight,” he says. “If someone’s going to rat me out, I feel they deserve pain. I’m just being honest.”

Van Soest says a lot of people wouldn’t talk to him for the film because they feared retaliation from Blanchard.

The filmmaker also notes that while Blanchard’s escapades may have started out as “a response to poverty or an issue with authority,” those motivations quickly faded. “There’s something else driving him. It was an obsession — he calls it an addiction. He had this incredible ambition to pull off these crimes and to achieve some level of notoriety,” Van Soest says.

Blanchard would devote months to carefully casing a bank, as we see in the documentary, but almost immediately after successfully walking off with a huge sum, he’d risk detection with a more brazen crime like sawing open an ATM on the street. “He clearly got a thrill from seeing how close he could fly to the sun,” the director says. “He wanted the pursuit; someone who wants to fly under the radar doesn’t strap smoke bombs across their chest.”

Though Van Soest’s film plays into Blanchard’s desire for fame, the director says he worried about glamorizing his subject too much and admits it was a tricky balancing act. “It’s easy to glorify him, because the genius of the crimes is head-spinning, and the preparation and work is to marvel at.”

Beyond the question of character, there’s no denying Blanchard’s brains and commitment. Detectives and prosecutors refer to him as a “genius.”

“He’s quite bright, and I’ll give him an A-plus for commitment,” says Larry Levasseur, a former Winnipeg police officer who with Mitch McCormick, another officer, led the team that caught Blanchard. “He put on an adult diaper and stayed in a building’s ductwork for 12 hours just in the hope of an opportunity.”

They chose to participate in the film because Van Soest was interested not only in telling Blanchard’s story but also in their determination to take him down. “To speak on what Blanchard did is to glorify it, and I worry about him being a celebrity,” McCormick says, “but we didn’t create that. We pushed and worked hard enough that he got caught. “

McCormick notes, “You can draw some comparisons with us and him — we’re both driven and spent long hours at work, and it was about the challenge and the thrill of the chase.”

Blanchard’s desire for notoriety may have led him to embellish his actions for dramatic purposes, Van Soest says. Although Blanchard would sometimes exaggerate, the director said he “decided to lean into the mythology around him and let the viewers make up their minds.”

“Some of the more fantastical elements make the story fun,” Van Soest says.

The director adds that police often confirmed the most outlandish acts — like when Blanchard lifted a badge and gun while escaping a police station or running over an officer with a stolen squad car. They happened almost exactly the way Blanchard claimed.

Peacock’s fast-paced and highly entertaining thriller pokes fun at true-crime culture, the pursuit of fame and the shallow excess of Los Angeles.

The stories around the Sisi Star jewel heist are the wildest, but Blanchard is mum about that, telling me that because he pleaded guilty only to possession of the jewel in Canada and not to stealing it, any admission could lead to his extradition to Austria.

McCormick and Levasseur speculate that Blanchard studied the sensors and cameras at Schönbrunn and hid out there overnight, stealing the jewel, replacing it with a fake (the switch wasn’t discovered for weeks) and then hiding again until the palace opened. “He did his homework and would have worked out compromising their system,” Levasseur says. “That’s his style.”

In the film, Blanchard looks like the proverbial cat with a belly full of canary, but in our interview, he mixed his pride with some efforts at remorse.

“At the time, I didn’t think I was hurting anybody else, but now I realize these weren’t victimless crimes,” he says, pointing out that people at banks or construction companies often came under suspicion because he would call in false tips, adding that they were transferred or lost their jobs. “There were other people involved, and I feel bad about it. Hopefully, people can learn from this.”

McCormick and Levasseur, however, are not buying the rueful tone. “We don’t really know him, and I think there are probably some good sides to him, but I don’t think there’s any remorse,” McCormick says. Levasseur agrees.

In the end, did Blanchard win? He lived large and served a short sentence (Canada’s penalties for nonviolent crimes are lenient). “I look back and say, ‘Yes, I won,’ but I did end up in prison,” Blanchard says. “I did lose a lot of friends — people don’t trust me — and it was harder to get employment.”

It was reported in 2017 by the Canadian newspaper the Globe and Mail that he was using an alias and working as a drone operator, among other jobs; he told me that he has been a consultant for a private detective in Vancouver, British Columbia, helping figure out how crimes were being committed.

As for his own life of crime, he says firmly, “That’s the past.”

McCormick and Levasseur scoff at that idea. McCormick says that when he retired from the force, he had a hard time adjusting to being just “Mitch,” and he suspects Blanchard would find it harder to shed his former life. “He can’t turn it off.”

“You have to take anything he says with a couple of grains of salt,” Levasseur says. He believes viewers “have good common sense and can weigh out what they hear and see and make their own decisions.”

Van Soest doesn’t take a stand. “I don’t have any evidence he’s involved in anything larger or nefarious,” he says. “So I liked leaving the question of whether he is still committing crimes open.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.