How two Hollywood stars plan to save a team, and a town, ‘desperate for a lifeline’

Coal and steel built Wrexham, a market town wedged between the Welsh mountains and the lower Dee Valley in northern Wales. But soccer has long sustained it.

The city’s team was formed in 1864, at the height of the Industrial Revolution, making it the third oldest in soccer history. And the fortunes of team and town have risen and fallen together ever since.

Both have been in steep decline lately.

Wrexham’s Queensway neighborhood, two miles north of the soccer ground, was recently ranked by the Welsh government as the third-most impoverished area in the country, making the bronze statue in the city center — a tribute to the area’s long-shuttered mines and steelworks — a taunting reminder of better days gone by. The team, which has dropped to the bottom rungs of British soccer, nearly folded a decade ago before supporters raised $120,000 in seven hours to save the club’s place in the lowly National League.

Now, the town and the team are waging a comeback. And if that sounds like a Hollywood script to you, you’re too late.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

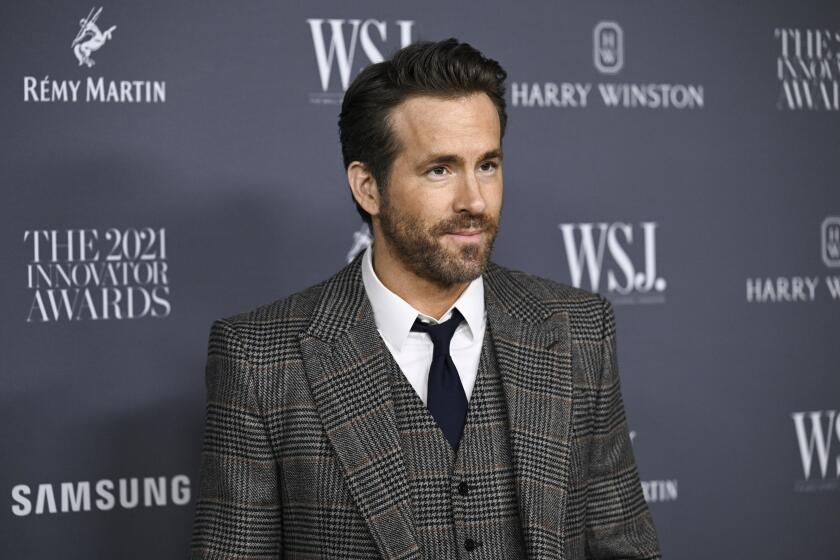

Nearly two years ago, actors Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney bought the team in hopes of turning it around and, not coincidentally, documenting on camera how they did it. That transformation remains a work in progress — the club is fifth in the league standings in its third season under the new owners — but the docuseries it inspired, “Welcome to Wrexham,” premieres Wednesday on FX.

“I thought it was a wind-up,” Wayne Jones, who grew up less than 100 yards from the city’s stadium and now runs a pub that is even closer, said of the Reynolds-McElhenney rescue. “When I went to discover there wasn’t a wind-up, I just thought we’d hit the jackpot. Wrexham has been through the doldrums over the last two decades, and we were desperate for a lifeline.”

How desperate? The Supporters Trust, a fan-run coalition that had managed the team for the last decade, voted 98.6% in favor of the actors’ approximately $2.4-million takeover bid in February 2021.

“Deep down, people were just excited,” Jones said. “They couldn’t quite believe two Hollywood A-listers were prepared to take over a fifth-division football club.”

European soccer has long had a love-hate relationship with U.S. owners, who are valued for their money and business acumen but reviled for their ignorance of the game’s history and tradition.

Nine of the 20 teams in the Premier League, the top level of professional soccer in the U.K., are run by Americans — among them Red Sox owner John Henry, who owns Liverpool; the Rams’ Stan Kroenke, who owns Arsenal; and Dodger co-owners Mark Walter and Todd Boehly, who recently bought Chelsea. Former Dodgers owner Frank McCourt owns iconic French club Marseille, and eight first-division clubs in Italy also have U.S. bosses.

They aren’t always greeted warmly.

“There is a tendency at first to say, ‘What’s the agenda of that person coming in?’” said Boston billionaire James Pallotta, a former co-owner of Italy’s A.S. Roma.

“There’s an off-the-bat skepticism, like, ‘Well, you guys live in the U.S.A., how can you run a club from so far away?’,” agreed Stuart Holden, who played for the U.S. in the 2010 World Cup and is now a part-owner of Spanish club Mallorca.

Nor does it always go well. In 2016, when former Dodgers catcher Mike Piazza bought A.C. Reggiana, a troubled third-tier Italian club, he was regarded as a hero. Two years later, the club was bankrupt, its offices closed, and Piazza had lost millions.

Freaked out by Ryan Reynolds’ break from making movies? The actor explained the ‘why’ and ‘for how long’ at an event this week.

Reynolds, the actor behind Deadpool, and McElhenney, creator and star of the long-running FX comedy “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” were well aware of that history. They knew they hadn’t bought a soccer team as much as they had purchased a part of the city’s soul. And that required special handling.

“We’re putting the community first at every turn,” McElhenney said. “So every time we make a decision or try to make an adjustment or pick a direction, we’re always seeking the counsel of people who are there on the ground. ‘Is this the right thing for the community? Do we believe that this is what’s going to create a winning formula in the short term, and in the long term?’

“We definitely approached this with a tremendous amount of respect and reverence.”

Like many good ideas, Wrexham’s soccer club came to life in a pub, when members of the city’s cricket team settled on the sport as a way to stay fit during the long winter months. That watering hole, the Turf, is now run by Jones, who has been a fan since the night he snuck out of his parents’ house and into the Racecourse Ground, the team’s ancient stadium, as a 10-year-old.

And like many of the 65,000 people who live in greater Wrexham — pronounced “Rek-sm,” with a silent W — he believes the town and the team are two sides of the same coin.

“The football club absolutely bonded the community. People live and breathe football in this town and have dug it out of many trenches, financially and emotionally, over the years,” said Jones.

“It’s literally everything, you know? I don’t even want to think or comprehend what would happen to Wrexham as a community and economy if the football club were to fold. It would be catastrophic.”

Yet that seemed inevitable before Reynolds and McElhenney took over.

The British soccer pyramid is a tiered structure with the top four levels, the league system, consisting of 92 professional clubs. And though Wrexham never made it to the top-tier Premier League, it spent 87 consecutive seasons in the league system, winning a record 23 Welsh Cups, before poor ownership and financial troubles — including a debt of nearly $5 million — saw the team fall to the fifth-tier National League in 2008.

It was as if a Triple A baseball team had suddenly dropped to the lowest rungs of the minor-league ladder.

Series creator and actor notes a key distinction between the shows: ‘Mythic Quest’ characters feel real, ‘Sunny’ ‘seems to take place on Mars.’

Attendance, a major source of revenue in a league without a TV deal, plummeted. The fans took over the team, but they lacked the money to upgrade the roster or keep up the historic Racecourse Ground, which dates to 1807 — older than the sport it now hosts.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which closed the stadium to fans altogether, should have been its death knell. But in fall 2020, Reynolds and McElhenney called. For their docuseries, they needed a distressed European soccer club that had history, a supportive community and a reason to think it could claw its way back.

Wrexham fit the profile.

“They’re playing for their lives,” Reynolds said of the players, some of whom were delivering pizza on the side to make ends meet when the actors came on board. “They don’t have multimillion-dollar contracts to kind of rest on their laurels. You can see the passion. They’re playing with every last drop of their blood.”

Buying the club was just the opening act. In European soccer, teams can be promoted to a higher league or relegated to a lower one depending on their performance. For Wrexham to be promoted back into the league system, it would either have to win the 24-team National League or finish in the top seven, then win a three-round playoff.

In the actors’ first season as owners, Wrexham missed the playoffs by a point. To correct that, they hired a new coach, Phil Parkinson, and a chief executive, Fleur Robinson, both of whom had extensive experience in the upper levels of the league system.

Robinson said Reynolds and McElhenney, who admit their knowledge of soccer is limited, haven’t interfered with her work.

“They’re invested. They want the best. They come up with ideas,” she said. “But at the same time, allowing the relevant people within the club to get on with their roles. They’re very open in terms of the knowledge that they have. It’s a bit of a learning process for them.”

In rebuilding Wrexham’s roster, Robinson spent a reported $236,000 — an unheard-of figure in a league where salaries average less than $50,000 — to sign free-agent striker Paul Mullin, then reportedly invested more than $350,000 combined on center backs Ben Tozer and Aaron Hayden. And while that got the team into the playoffs, Wrexham lost in the semifinals.

Along the way, global brands TikTok and Expedia replaced a local trailer manufacturer as the team’s main sponsors, and the club spent millions to replace the field and renovate the 10,500-seat Racecourse Ground. The community responded in kind, with season-ticket sales tripling and average attendance soaring to nearly 10,000 this season.

Meet the cast, go behind the scenes on key episodes and read our analysis of the inspirational sports comedy that TV fans can’t stop talking about.

Three weeks ago, Mullin, who scored 30 goals in his first season at Wrexham, signed a contract extension.

“We’ve grown significantly in the 18 months since they’ve taken over,” the Turf’s Jones said of Reynolds and McElhenney. “They’ve been brilliant. They carry on the way they’re going, the sky’s the limit.”

The city has bounced back too. An economy once dependent on heavy industry and coal mining has transformed into one centered on high tech, manufacturing and technology. The unemployment rate of 3.9% is more than a third lower than it was a decade ago.

But the team remains in the fifth-tier National League, and despite the actors’ investment, it’s 2-1-1 four games into the new season. So while “Welcome to Wrexham’s” freshman run is in the can, Reynolds and McElhenney aren’t done yet.

Promotion, if it comes, will have to wait until Season 2. In the meantime, they’ve delivered hope, and that may be even more important.

“We’ve gone through so much heartache over the last 20 years, and we’ve had some really bad owners and some really bad luck and some really bad calls against us,” Jones said. “I just feel that we bottled all that up over the last few decades.

“It’s our turn to have a bit of time in the sun.”

###

‘Welcome to Wrexham’

Where: FX

When: 10 and 10:38 p.m. Wednesday

Rating: Unrated

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.