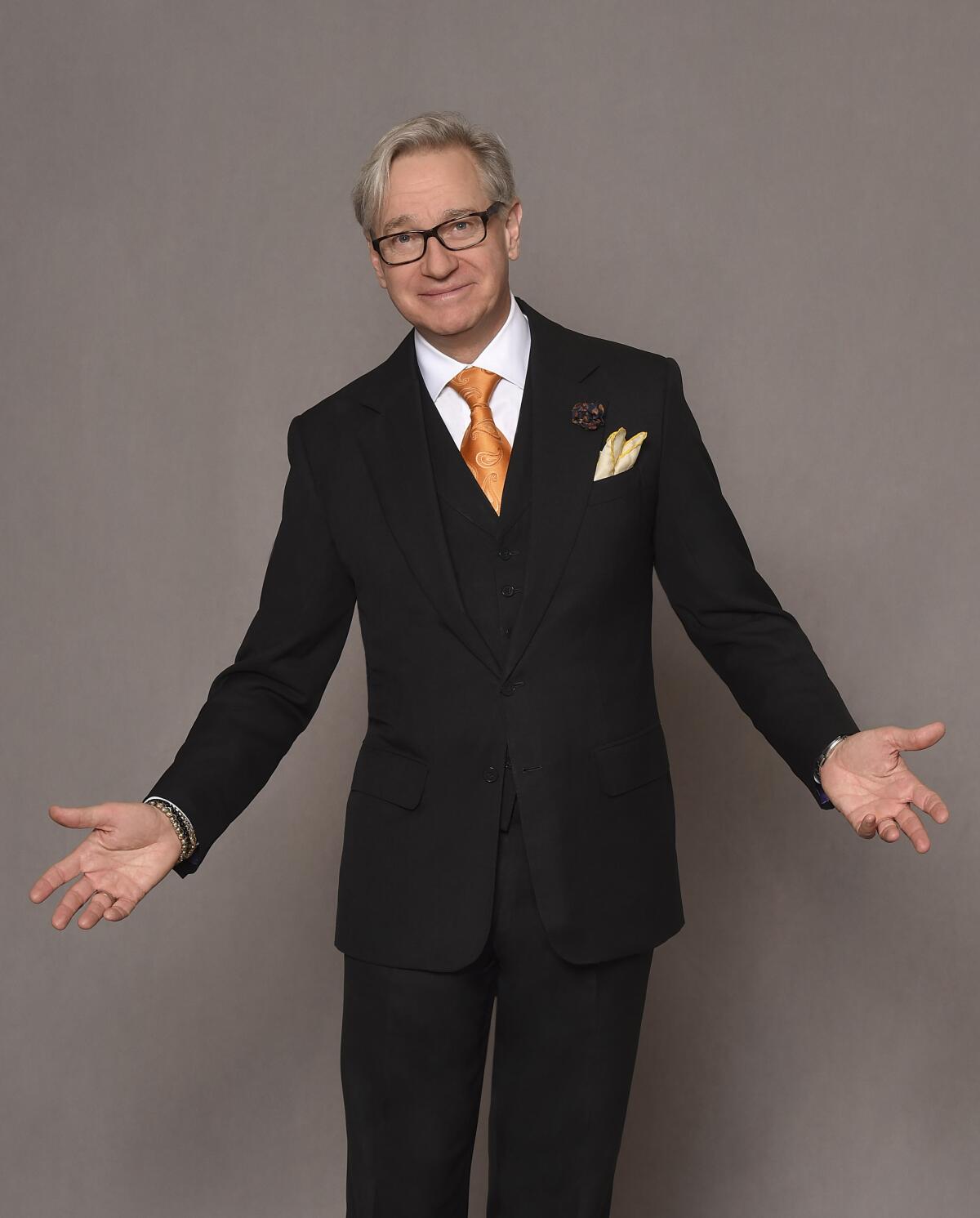

Producer Paul Feig has an ‘unheard of’ hit rate. Here are his secrets to success

Some will remember Paul Feig as biology teacher Mr. Pool on “Sabrina the Teenage Witch,” but his real adventures in pop culture began with the creation of “Freaks and Geeks,” which launched his career behind the camera. Afterward better known as a director of film (“A Simple Favor,” “Bridesmaids,” “Spy,” the gender-flipped “Ghostbusters”) and television (notably “The Office,” “Arrested Development” and “Nurse Jackie”), he has been recently busy as a producer of both, through his FeigCo, and of digital content, via Powderkeg, an “incubator” he co-founded with Laura Fischer, “dedicated to elevating female and LGBTQ creators and filmmakers of color.”

Though he has not had a show of his own creation since the 2015 sci-fi comedy “Other Space,” Feig’s production company, which was also behind “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” and “Love Life,” recently had two series premiere on the same day. Fox’s faux documentary “Welcome to Flatch,” developed by Jenny Bicks (“Sex in the City,” “Men in Trees”) from the BBC’s “This Country,” stars Sam Straley and Holmes as cousins, immature yet striving, proudly critical residents of an eccentric Ohio small town. “Minx,” on HBO Max, is a period aspirational workplace comedy from Ellen Rapoport, about the first erotic magazine for women, sort of like “The Deuce” crossed with “Good Girls Revolt” crossed with “GLOW.”

It’s worth exploring the Powderkeg productions as well. These include the short films produced under the banner Powderkeg: Fuse and set among less-represented communities of Los Angeles, among them Talia Osteen’s “Shabbos Goy,” Thembi Banks’ “Baldwin Beauty” and Lizzy Sanford’s “Freckle and the Shih Tzu.” The company also has produced the Snapchat series “Everything’s Fine,” about a young woman with bipolar disease trying to make it in the music business; and “East of La Brea,” which can be seen on Powderkeg TV’s Instagram account, about the friendship of two young Muslim women, one Black, one Bangladeshi. Powderkeg also is producing “The Doctor Is in,” a comedic drama in podcast form, starring Alison Pill as a veterinarian dealing with supernatural creatures.

I recently spoke with Feig about his approach to producing.

We surveyed The Times TV team to come up with a list of the 75 best TV shows you can watch on Max (formerly HBO Max). And yes, your disagreement is duly noted.

It seems natural to begin talking about your producing career by talking about Judd Apatow, who produced “Freaks and Geeks.” What did you learn from him?

What I learned with Judd is that a good producer has creative thoughts, helps dig you out of holes that may occur either through feedback from the network or when you get tied up in something you can’t figure out. They’re good protectors of your vision, willing to fight the battles on the front line so you as the creator can do your thing and not get overwhelmed by politics; they’re supportive and keep the train moving. As a producer you want to balance your ideas with the creator’s and not just dictate a different voice to the show.

A good producer teaches you the realities of the business, and is good at tamping down the natural instinct of someone who’s a first-time showrunner or creator — or is just on fire about their ideas — to explode at any moment. Someone gives you a note: “How dare they!” And a good producer’s like, “All right, calm down. There’s something in that note, let’s listen.” It’s not to compromise your vision, but you’re in a business. If you’re just a person that says no no no to the people in charge, you’re not going to work anymore. I tell students or anybody I work with, “Look for the germ of truth in the note.” If it’s, “We don’t understand this, we think it could be stronger,” that’s a valid note, usually. Sometimes it’s not, but let them have a few victories.

Were you and Judd ever at odds?

We were really in sync on the whole thing. We cruised through the selling process — I wrote the script, on spec, and sent it to Judd and he had a couple of small notes, but that was it. And when NBC got it they were like, “Don’t change a word.” And who ever hears that in this business? It’s every writer’s dream. The eye-opening moment for me was when we were moving towards production, Judd was, like, “OK, let’s tear the script apart.” And I was like, ”Wait, what?” And it was really this two weeks of growing up. His whole thing, and he learned it from Garry Shandling, was, “You’ve got the script, it’s in great shape, if you’re hard on it and try different things all you can do is make it better, and if you don’t you’ve got the original script.”

Was “Freaks and Geeks” different from what you experienced with producers afterward?

Well, after “Freaks and Geeks” I couldn’t sell many shows, so I was working more as a director on other people’s shows. But I’ve been pretty lucky to get to produce a lot of the stuff I’ve done in my career, or work with a producing partner of my choosing, or another producer who’s on an equal footing with us, so they’re giving input but not dictating to us.

When you’re producing your own projects, do you find it necessary to have some kind of outside critical voice?

I do; I just want to make sure it’s always of our own choosing. It sounds a little like stacking the deck. But my producing partner in movies for seven years was Jessie Henderson, and now it’s Laura Fischer, and they’re both super-smart, realistic, tough-on-material people who are never going to go, “Oh sure! Whatever!” I deputize everyone around me — just call me on stuff. And that was really something I learned when I worked under Greg Daniels on “The Office.” He deputized all the way to the catering people; he would grab the security guy from the parking lot and pull him into the editing room and ask, “What do you think of this?” And he would listen, because everybody’s a valid member of the audience. If you go into it that way, you’re not just in your own head and up your own ass, which is the easiest thing to have happen.

One legacy of “Freaks and Geeks” was the mentoring of the young cast. With Powderkeg, especially, you’re still working with younger generations.

In this business you never have, like, power power. You have things you can get made if you play your cards right; you have a better chance if you have a track record. But you are still at the mercy of the industry, and they can change their mind on you at any point. That said, if you have any kind of ability to help people through the power you currently have, to get their voices out there the way you were able to when somebody protected you, you do have to pay it forward. I am a strong believer in using every bit of clout we have to do that. I get tired of the old voices; I get very tired of my voice. And so when I produce something, most of my effort goes into putting it together, finding the right people, making sure they’ve got the best people around them, and once something has proven it works, I want to get out of the way.

You have a well-deserved reputation for promoting women in film and films about women. The Athena Film Festival gave you its first “Leading Man” award.

They’re the only stories I’m interested in telling, really, at the moment — and I feel like it’s been most of my life. Maybe it’s just that growing up I didn’t see that many done, except for old movies, I’ve always been friends with women and enjoy their senses of humor and the way they interact and tell stories. But now with Powderkeg, it includes filmmakers of color and LGBTQ people. I’ve seen enough stories about white men.

What’s your ratio of pitches to what gets made?

It’s getting better. I went through a very frustrating period when I started my TV company, like four or five years ago, when we couldn’t sell anything. We were out pitching — you always leave these pitches like, “Oh my God, we’re going to have a bidding war,” and then it’s like no, no, no. I’d call my agent sometimes: “I’m closing my TV division, TV hates me for some reason. From ‘Freaks and Geeks’ on, I can’t keep a show on the air to save my life.” But then it just started clicking in. We started pitching more commercial projects and with the streamers there was more content that was needed. Our hit-to-miss ratio, I would dare say we’re above 50% at the moment, which for us is unheard of.

Do you think there’s a Paul Feig brand, that when people see your name they expect anything in particular?

I’d hope they’d first say, “Oh, it’s going to be really fun, even if it’s dark, it’ll be good-natured and be uplifting ultimately.” I hope they’d expect an underdog story, ’cause those are the stories I’m really interested in telling. I want to be a mark of quality but I don’t want to be a mark of boring quality; If my career were summed up in one word and that one word was fun, I’d be really, really happy.

Let’s talk about your new shows. There’s “Minx.”

Ellen Rapoport pitched the idea to us, which is basically a fictional retelling of the birth of Playgirl magazine. What I liked about it is it’s not a story about porn, it’s not about sex, it’s just about nudie magazines — there’s such a nice innocence about that now, in the day of the Internet. But it was really the way that Ellen pitched it. The characters were just so funny and so well realized, and again it was a total underdog story. A scrappy young feminist is trying to start a scrappy young magazine and she starts up with a scrappy adult-magazine publisher who’s trying to get respected, and it all spoke to me as this beautiful way to show the American Dream at its scrappiest, if I may use that word one more time.

That first episode features more full frontal male nudity than possibly the entire history of television combined. How does that fit with the Paul Feig brand?

Well, the funny thing is you watch my movies, there’s hardly any sex scenes and there’s never any nudity. If there’s a sex scene it starts wide and pushes in on somebody’s face. It’s just like, “Can we please get through this because I’m so uncomfortable.” But what I love about the show is, we immediately make it not titillating; the moment Joyce walks into Bottom Dollar [the publishing company], you go, “Oh, it’s just a factory.” It could not be less sexy. You’re not coming here to get turned on, you’re coming to watch a bunch of people trying to run a business that just happens to be about naked people.

On “Welcome to Flatch,” you directed three episodes and wrote two. What inspired you to get more involved?

I love to write those kind of small characters in a small town; it’s what “Freaks and Geeks” was, really. The fun thing about that show is, a lot of weird things you did when you were younger you can write episodes about; Kelly and Shrub are so developmentally arrested, anything I did as a kid I could make them do. Like the third episode, when Kelly starts her own dance school, my next-door neighbors and I did that, we opened a dance school when we were like 12 years old, and I invented these really crappy dances and charged kids in the neighborhood. And everybody complained and wanted their money back because the dances were so dumb.

The mockumentary is such a familiar form, a certain sameness can set in. But “Flatch” gets past that.

I feel that the mockumentary — I don’t like to say mockumentary anymore because it sounds like it’s making fun of the people in it — but docucomedy is my favorite way to do television comedy, having done “The Office” and “Arrested Development.” I know how fast you can go, and how immediate it can be. Every time you do a take you get the whole scene. A show like this, you’ve got to stock it perfectly with actors who can be natural, be hilarious, have improv skills, but also are good actors so they can do what we write.

I’ll tell you one interesting story about the pilot. We were getting ready to do it right when the pandemic was starting, and shows were just shutting down all over the country, but we were in North Carolina and there was a kind of feeling like, “Maybe we can keep going, it hasn’t hit here yet.” And we got halfway through the first day trying to be as safe as we could with what we knew, and there was one scene in this little room with two actors watching TV and I had a freak-out moment: “We’ve got to shut down, we don’t know what’s going on and we’re in this little room breathing each other’s air.” But we had the foresight to pile everybody out to this park and shoot a few hours documentary-style, just really loose, and that’s what we edited together for the presentation. And that’s how we sold the pilot off a one-day shoot.

‘Minx’

Where: HBO Max

When: Anytime

Rating: TV-MA (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 17)

‘Welcome to Flatch’

Where: Fox

When: 9:30 p.m. Thursday

Rating: TV-14-DL (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 14, with advisories for suggestive dialogue and coarse language)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.