Every great story needs a villain — and for the Los Angeles Lakers, the biggest bad of all has always been the Boston Celtics.

In Episode 2 of “Binge Sesh,” hosts Matt Brennan and Kareem Maddox explore the most storied rivalry in NBA history. From Larry Bird to the “Beat L.A.” chant, we examine how the Celtics — embodied in HBO’s “Winning Time” by the legendary coach and general manager Red Auerbach — came to be the Lakers’ quintessential opponent, for reasons that went way beyond the basketball court. Warning: This episode contains profanity.

Listen now

Or check out Episode 1: How Jerry Buss, Magic Johnson and the Showtime Lakers created the modern NBA

Jeff Pearlman: It’s a cold day in Boston.

Kareem Maddox: You’re the Lakers, and you’re the visiting team.

Pearlman: The visiting locker room is going to be freezing. The heat won’t work.

Maddox: That’s the worst when you’re trying to change or when you’re already sweaty.

Pearlman: You’re staying at whatever hotel. Amazingly, that name of the hotel shows up in the newspaper.

Maddox: Now you have Celtics die-hards knowing where you’re sleeping.

Pearlman: And just by coincidence, at 3 in the morning, a fire alarm is being pulled in that hotel and everyone has to leave, and then they go back to the room and, oh, it’s 5 o’clock and it’s pulled again.

Maddox: Now you’re exhausted. And when you do eventually show up at the Boston Garden ...

Pearlman: ... there’s dead spots in the parquet floor that the Celtics knew but the visiting players didn’t know. You’re dribbling the ball. The ball all of a sudden hits a flat spot.

Maddox: Welcome to basketball hell.

READ MORE >>> There’s no place that can compare with Boston Garden

Maddox: I’m Kareem Maddox, basketball-playing podcast host.

Matt Brennan: And I’m Matt Brennan, Irish Catholic boy from Boston, Mass., and TV editor of the Los Angeles Times.

Maddox: And this is “Binge Sesh.” This week we’re checking out Episode 2 of “Winning Time,” in which we got to meet some of the Lakers’ forever rivals, the Boston Celtics. So Matt and I are talking rivalries: what makes them, and what made up one of the most notorious ones from the 1980s.

Brennan: So, Kareem, you went to Princeton, right?

Maddox: Yes, I did.

Brennan: So who’s your rival?

Maddox: We call them “those guys down in Philly.”

Brennan: Wait, really?

Maddox: Yeah, we don’t say the name.

Brennan: Um, for those of us who are not intimately familiar with “those guys down in Philly,” who does that refer to?

Maddox: The University of Pennsylvania.

Brennan: What’s your most vivid memory of that rivalry?

Maddox: Being made to run by my coach, who was also a Princeton alumni.

Brennan: OK, describe to me, I don’t even know what you’re talking about. Describe to me what the running is, where you’re running, how you’re running, what the purpose of the running is.

Maddox: Where we’re going?

Brennan: Yeah.

Maddox: Yeah. So, nowhere. We had to run suicides. So it’s like, basically, start on the baseline, so, underneath the hoop. You run to the free throw line and then back; and then to half court and then back; and then the other free throw line, back; full court, back.

Brennan: That sounds horrible.

Maddox: They’re not fun. And we had to do those because our coach didn’t like thinking about those guys down in Philly, but that was the week of the game against those guys down in Philly.

Brennan: What you’re telling me is that your coach punished your team before the game against your biggest rival — just because they exist.

Maddox: Yes, that’s exactly what happened.

Brennan: This is very much like a Lauren Conrad versus Heidi Montag situation.

Maddox: Who’s that?

Brennan: OK. I’m making a mental note to introduce you to “The Hills.” But what I meant by that is that rivalries don’t just apply in sports, but we’re going to focus on how they operate in sports today and specifically how they operate for the Lakers and their archrivals, the Celtics. But before we get to that: I actually got to talk to a couple of professors who study rivalries.

Joe Cobbs: I’m Dr. Joe Cobbs and I’m co-founder of the Know Rivalry Project with Dr. David Tyler, who’s at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Brennan: That’s the K.N.O.W. project. So, their project looks at a lot of different sports rivalries.

Cobbs: The ingredients that go into them and some of the outcomes or the results. What are the differences? And how do those contribute to fans’ reactions?

Brennan: So the first obvious question I had was simply: How do you define rivalry?

Cobbs: An opponent or an out-group that poses an acute threat to your in-group. That could be a threat to esteem, or it could be a realistic threat to your in-group’s accomplishment. The greater the threat, the more opportunity there is also for enhancement of self-esteem if you can overcome that threat.

Maddox: So in a way, being a part of a rivalry as a fan is sort of like gambling with happiness. The more heated the rivalry, the bigger the payoff if your team wins. But if they lose —

Brennan: Exactly. And for a long time, Lakers fans lost that gamble a lot.

So we saw in the first episode of “Winning Time” that the lopsidedness of this rivalry pretty much drove Lakers great Jerry West crazy.

[“Winning Time” clip: Jerry Buss character: When he retired, they made his silhouette the logo of the league. Jerry West character: You think that made me f— happy? Well, it didn’t!]

Maddox: Lakers legend Jerry West was sick of his Lakers losing. In the ‘60s and ’70s, the Lakers went to the finals nine times — nine times! — but only won one of those championships. And six of the eight times they lost, it was to the Celtics.

Brennan: Beat L.A., baby!

Maddox: Don’t say that.

Brennan: But that history is part of what makes rivalries tick, according to the guys from the Know Rivalry Project.

Cobbs: That’s really kind of what the rivalries are, is they’re a narrative that takes place over time, that builds up the meaning of that opponent more than other opponents. And the narrative of Lakers-Celtics is just so deep with different layers. And so one of those layers is certainly those superstars of the ’80s and ’90s. But the superstars go back in this rivalry even before Bird and Magic.

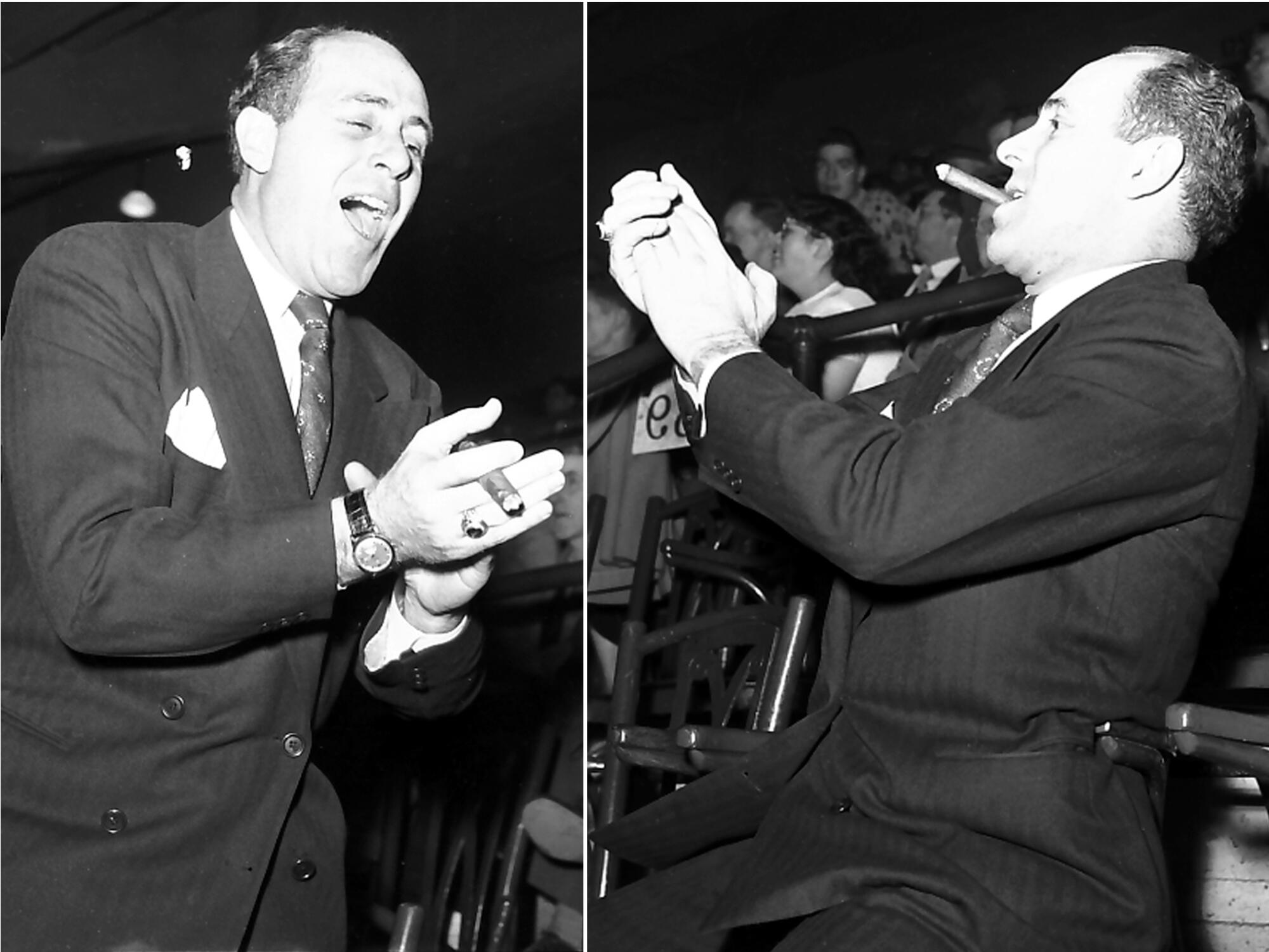

Maddox: In Episode 2 of “Winning Time,” we meet one of the superstars that cemented this rivalry into the book of rivalries: Red Auerbach.

[“Winning Time” clip: Jerry Buss character: But I’d still like to meet the past. Where’s this Auerbach? David Stern character: Oh, you mean the Pope? Follow the white smoke.]

Brennan: My perception of Red Auerbach, who was before my time, has always been as this red-faced, cigar-chomping cartoon villain, except since he was affiliated with my hometown team, he was the hero. And my idea of him, I think, lines up quite a bit with the caricature that we’re introduced to in “Winning Time.”

[“Winning Time” clip: Jerry Buss character: Red Auerbach. Winner of 13 rings, seven of them against our club, no losses. If you’re a Laker, he’s the devil incarnate. If you’re from Boston, chances are you’re Catholic, but you’d sell your soul for him.]

Maddox: It seems like he really leaned into this reputation as a villain. For example, he once punched the owner of another team because he thought their team had messed with the height of the hoops. Then there was that other time when he ran onto the court to challenge Moses Malone, a giant of a human, to a fight.

Brennan: Michael Chiklis, who plays Red in the show — his version of the character does not dispel that image. He’s not just depicted as arrogant, aggressive and ruthless. He describes himself that way.

[“Winning Time” clip: Red Auerbach character: Championships aren’t won, they’re taken. By men like me, who cut your heart out and still sleep like a baby for one more banner in the rafters. Because I don’t want to win, I need to. And it doesn’t make me happy, it makes me a miserable f— bastard.]

Maddox: He does seem like the Penguin from the old Batman movies, but there is another side to his legacy: When Red entered the league, it was 100% white. He became the Celtics coach in 1950. And that team selected the first Black player to be drafted into the NBA. He was the first coach to start five Black players in a game. He traded away two good white players to be able to draft Bill Russell, who of course would go on to win 11 rings with the Celtics and become a Hall of Famer. And then when Red Auerbach became the general manager, he made Bill Russell the NBA’s first Black head coach.

Brennan: So I’ve been doing a little Red Auerbach googling ’cause I was curious about this.

Maddox: I bet you have.

Brennan: I’m a nerd. What can I say? Um, I came upon this quote from Celtics great Bob Cousy, who actually once said of Auerbach, “He was certainly no leader of civil rights. He was completely one-dimensional. His entire life was win.”

READ MORE >>> No one beat L.A. like Auerbach did

Maddox: Yeah, exactly. So we can’t really know what motivated Red. We don’t know how and if he was supporting Bill Russell when he faced some serious acts of racism in Boston. Rachel Laws Myers is the author of “Race and Sports” and an expert in the area. She told us about the most infamous example.

Rachel Laws Myers: When Bill Russell was with the Celtics, you know, this man had somebody break into his own home and defecate on his bed. When you think about that personal violation, to play on the national stage, to win national championships, to be lauded and praised, but then to come home to your sanctuary and know that somebody broke in, all types of racial slurs on his walls. And to literally defecate on your bed. I mean, that’s hatred to the highest degree.

Maddox: What Russell faced in Boston spilled over from politics into professional sports. And not just the NBA. That’s what Jeff Pearlman, who wrote the book that “Winning Time” is based on, told us was happening on the eve of the “Showtime” era.

Pearlman: I feel like at that time period, people weren’t willing to embrace the quote unquote Blackness of a sport league. I mean, at the same time period, the NFL was basically not allowing Black quarterbacks. So, like, you turn on an NFL game, your star is going to be a white guy. Major League Baseball, most of the stars are white guys. You go to the NBA, it’s a quote unquote Black league, you know, and and it just wasn’t really embraced.

Brennan: And at this time, Boston in particular was associated with racism in the public imagination. Which, though it breaks my heart to say it, makes sense.

Maddox: Why does that make sense?

Brennan: The Boston busing crisis.

So I talked to the team behind a podcast called “Fiasco.” They did a whole season that explained what the Boston busing crisis was really about. Because it was about a lot more than busing. Sam Graham-Felsen was a producer on the series.

Sam Graham-Felsen: I think a lot of people have heard of busing in Boston but don’t know much about it. And the rest was history. We made a seven-part podcast about it.

Brennan: And it became obvious to Sam that this was all really a fight over school desegregation still going on 20 years after Brown vs. Board of Education. The host of “Fiasco,” Leon Neyfakh, explained the situation:

Leon Neyfakh: Boston is a Northern city where people thought of themselves as progressive on race and there’s sort of a pride in being not the South. But in fact, the schools in Boston were utterly segregated, and in the schools where the Black students went were much, much worse, much, much poorer because they didn’t have the same resources.

And busing was an attempt to fix that.

Brennan: The situation came to a head in Boston in 1976, America’s bicentennial year.

Graham-Felsen: You had an overwhelmingly Black neighborhood called Roxbury and you had an overwhelmingly white neighborhood called South Boston. These neighborhoods were not terribly far away from each other, but they were far enough that you couldn’t walk from one neighborhood to the other if you were a high school kid. So the only way to desegregate was to use buses.

Louise Day Hicks, who was one of the central characters, she just really latched on to this idea of, of busing. She would always say, like, “I’m not against, you know, Black kids. I’m not for segregation. Diversity is a nice thing, but I I hate busing, I don’t want to put my kids on a bus and make them drive for hours to some scary neighborhood far away.” So they made it all about the tactic of busing to obfuscate from the fact that they didn’t really want to mix white kids and Black kids.

Brennan: There’s a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph from 1976 shot in Boston’s City Hall Plaza. It’s called “The Soiling of Old Glory,” and it condenses all the forces at play here. Leon Neyfakh described it like this:

Leon Neyfakh: What you see when you look at the photo is a white guy. He’s young, but he’s not a kid. He’s got kind of long hair. He kind of almost looks like a hippie, which I think makes it a little even a more a little more sinister. He looks like he’s holding a massive spear and the flag is dangling at the end.

As your eye sort of follows this flag, what you see is that the person on the receiving end of this spearing is a Black man wearing a suit who is sort of crumpled almost. He’s been destabilized, and he’s being sort of held by other white people. You can’t really tell if he’s getting up or if he’s falling. And it looks, you know, as you look at it, like he’s being restrained and this guy with the spear is trying to lunge at him with the flag, using the flag as a weapon.

Graham-Felsen: Yeah, I mean, it looks like he’s trying to stab the guy to death with the American flag. We quoted from a letter that somebody wrote to the Boston Globe where the writer says something like, “If these people really were anti-busing, then why didn’t they go attack a bus? Instead they attacked a black lawyer. What does that have to do with a bus?”

Neyfakh: Yeah.

Graham-Felsen: So that said everything to us.

Brennan: So I want to be clear here that the point of saying all this is not to suggest that Boston was uniquely racist. School desegregation was fought tooth and nail by white parents and public officials in city after city, North and South, over the course of decades. In many ways, it still is. But for several reasons — because the so-called busing crisis was so recent, because “The Soiling of Old Glory” was disseminated so widely — Boston became the symbol of the white backlash against civil rights.

We’ll be right back.

::

Maddox: All right. I’m going to describe an NBA legend, and you have to guess who it is.

Brennan: Oh, OK.

Maddox: OK. Not your strong suit, but we’ll see how this goes. So 6-foot-9, about 220 pounds. Great athlete. Grew up poor in college, led their team to the NCAA championship and is an all-time great.

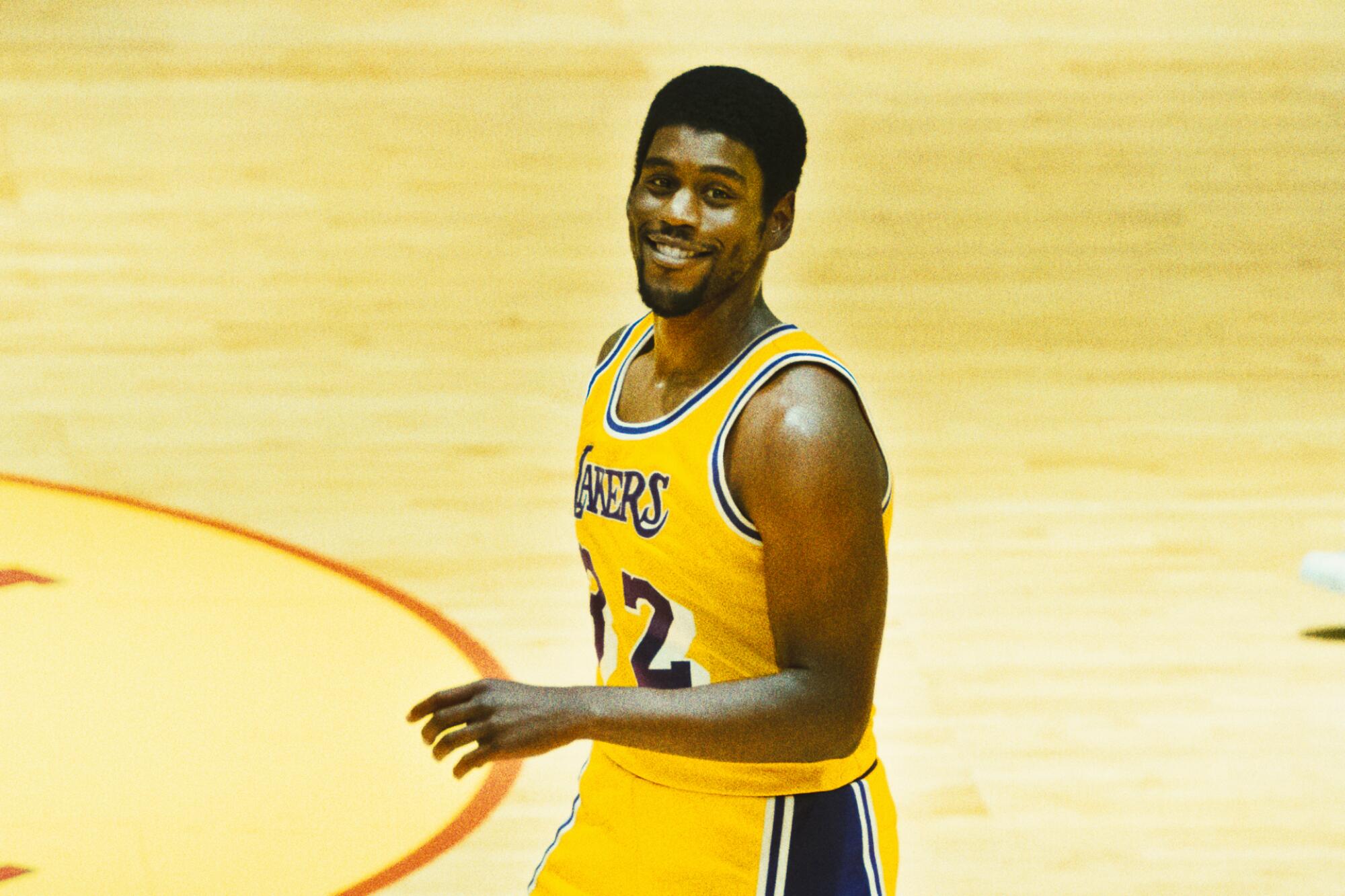

Brennan: OK, we did it, we covered this in Episode 1, and I did my homework. Magic Johnson.

Maddox: Wrong. It’s Larry Bird.

Brennan: Wait, they’re the same height?

Maddox: Same height, roughly the same weight, yeah. Larry had that mustache, though.

Brennan: I think what I want to say is that with that mustache, you’re not going to get a reputation for being glamorous.

Maddox: No, you’re not. No, it was.

Brennan: Sorry, Larry.

Maddox: It was. It was a tough, tough ‘stache.

Brennan: A tough ‘stache.

Maddox: Maybe the mustache was an ‘80s thing.

Brennan: One of the things that distinguishes Larry Bird and Magic Johnson is that Magic Johnson has this like megawatt smile and he walks into a room and everyone’s eyes turn to him and he loves the attention. And my read on Larry Bird was always that he hated the attention. He’s notoriously press averse.

Maddox: Right, he’s kind of unassuming. Which is interesting, too, because one of the things Larry Bird is known for is being an all-time s— talker.

Brennan: Wait, s— talking on the court? Like during a game?

Maddox: Oh yeah.

Brennan: How does that work? Like, you go up when you’re, like, close to the guy and you, like, whisper in his ear?

Maddox: I mean, it could be a gentle whisper.

Brennan: OK, sorry, I didn’t mean to sound romantic, but like, what do you say? What is s— talking?

Maddox: Yeah. So Larry Bird would just — he had this kind of untouchable attitude where he would just tell you how he was going to beat you. And then he would go and do it, and he was skilled enough to be able to do it.

He’s one of the most creative players in NBA history. If you see some of the things he did — I mean, a lot of people would argue, and they’re probably all from Boston, that he was as creative and as flashy as Magic Johnson, but just in a different package.

So, Brad Turner is a staff writer for the L.A. Times who covers the Lakers, and he told us this story from his experience about how much respect there was for Larry Bird’s skills.

Brad Turner: You go to the Black barbershop. And again, he comes on and it’s like, “I hate Larry Bird. I can’t stand Larry Bird, but damn, he’s good.” And the joke would be amongst my Black friends that he was not Larry Bird because he was so damn good. They would call him Larry Abdullah. Because there’s no way this white kid, this white man, could be that damn good. Yet he was.

Brennan: These narratives were all fueling the Lakers-Celtics rivalry at this time. What was happening in Boston, the racial aspect of Larry and Magic’s on-court battles — people took all of that material and ran with it.

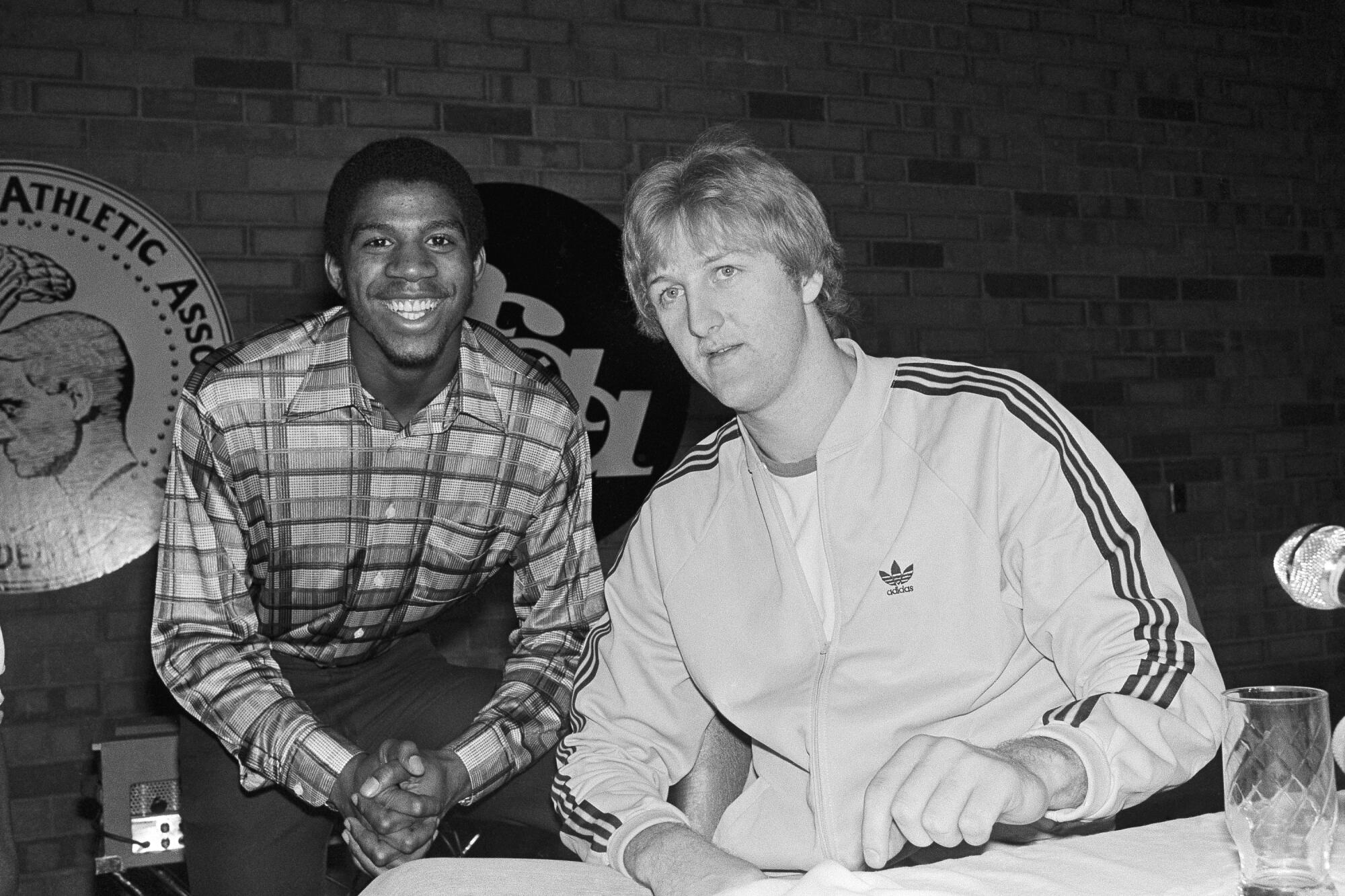

Cobbs: The media sometimes — this is speaking specifically about the Bird-Magic era. The media sort of creates one narrative, which in this case I would say is about sort of the cultural differences, the differences between the teams, the differences between the cities, the differences in appearance, you know, white, Black. But when you really dig into it and you listen to interviews by Bird and Magic and you read things that they said about each other, I think what drove the rivalry between them is really the similarity between the two of them. I think that’s where the competitiveness between the two of them came from.

Maddox: And they do have similar backgrounds. They both grew up poor. Magic, as we’ve already seen in the show, is from Michigan, the Detroit area. Bird was from French Lick, Ind. You know his nickname, right?

Brennan: The Hick from French Lick.

Maddox: That’s the one. They famously played each other in the NCAA Championship in 1979 — Larry Bird at Indiana State and Magic Johnson at Michigan State. (Magic won.)

Brennan: It’s sort of like at the pinnacle of every stage of their career, they ran into each other.

Maddox: Exactly. And you would think that would make them hate each other. But that’s not the case. Here’s Magic in an interview with the L.A. Times from a few years back.

Magic Johnson: Well, Bill, I like him now. You know, coming up in college when we met for the 1979 NCAA championship, you know, I had a real dislike for Larry.

Maddox: According to Magic, it all goes back to that classic “us versus them.”

Johnson: I just hate anybody in green. It was Larry. It was Kevin McHale. Because you had to hate the Celtics to beat them. Because when I got here, we were 0 for, I think, 8, and so you had a real dislike for them. But now, Larry and I are friends.

Brennan: As Jeff Pearlman told us, though, Americans seemed to take whatever priors they had and project it onto what was happening on court.

Pearlman: Boston was just, you know, it’s all a little cliche, but they were like the gritty, hard-nosed team and L.A. was the freestyling, high flying. And it was really in a way a lot of it’s really lazy. Larry Bird was a great athlete — not a good athlete, a great athlete. Kevin McHale was a great athlete. Magic Johnson worked his ass off, you know? James Worthy worked his ass off. The whole stereotype trope of it all just always was a little lazy, but it made for great drama.

Maddox: Matt, you know what else is great for drama?

Brennan: Suspense.

Maddox: Dun dun dun.

Brennan: Oh, I have a good story for you — when we come back.

::

Brennan: We established earlier in the episode that you know the “Beat L.A.” chant pretty well.

Maddox: Yes, I’m familiar with the haters.

Brennan: So you won’t be surprised that the chant first started in Boston.

Maddox: Sounds about right.

Brennan: What you might not know — I didn’t — is that when the chant originated, there wasn’t an L.A. Laker within 3,000 miles.

I actually came across the origin story in a 2018 piece by the Times sports columnist Bill Plaschke. So I decided to ask him about it.

Bill Plaschke: It started at a game that L.A. didn’t play.

It was in the Boston Garden during Game 7, the Celtics’ Game 7 playoff loss to the 76ers. This local attorney, Joel Semuels, was like, “If we can’t get in, if we can’t win it, L.A. sure as hell can’t win it.”

And he started screaming, “Beat L.A., beat L.A., beat L.A.,” and everyone was chanting it.

And you should know just for background that the “Beat L.A.” chant is the most universal, one of the most universal chants of all sports in any city. Anytime an L.A. team — you know an L.A. team’s arrived when you hear somebody’s chanting, “Beat L.A.”

Brennan: This game where the “Beat L.A.” chant originated was in 1982. The Celtics and Lakers had not played for an NBA championship for 13 years at that point. And they wouldn’t meet in the championship again until 1984. So what we think of as the ’80s heyday of this rivalry hadn’t even really started yet. And the terms of that rivalry were still so crystallized that a Celtics fan was worried about beating L.A. when there were no Lakers in sight.

To me, that shows just how important the narrative behind this rivalry was. It was that story that gave the rivalry shape, and in the ’80s, the long-suffering Lakers would finally begin to surge ahead.

Maddox: Well, there was just one problem.

Matt: Wait, what’s that?

Kareem: The Lakers need a coach.

::

Brennan: OK, I want you to give me your best s— talk. Like, I want you to s— talk me.

Maddox: OK.

Brennan: Pretend that I’m a foot taller and would actually be in competition. OK.

Maddox: All right. So what I would say is. Matt, you can’t guard me if I were you. I would if I were you, I would go home, take a look in the mirror and ask yourself why you think you’re capable of being on the same court as me. Like, seriously, what’s what gives?

Brennan: I love this. OK. You can get meaner. Like I have a thick skin. OK? You don’t have to hold back.

Maddox: This is a basketball. We’re playing basketball.

Brennan: Yeah, we’re playing basketball. I mean, you got to think of me as someone who you actually, like.... Pretend I’m — what are they called? — one of those guys from up in Philly.

Maddox: Hey, come get your son. Come get your son. He’s not. He can’t guard me. Come on. Somebody help someone who needs help right now.

Brennan: Mom, come pick me up.

Maddox: You’re not doing well, man.

Brennan: Kareem was mean.

Maddox: Now I feel bad. I’m sorry.

Additional resources

Larry Bird and Earvin “Magic” Johnson with Jackie MacMullan, “When the Game Was Ours” (2009)

John Feinstein and Red Auerbach, “Let Me Tell You a Story: A Lifetime in the Game” (2007)

Rachel Laws Myers, “Race and Sports: A Reference Handbook” (2021)

Leon Neyfakh, “Fiasco: The Battle for Boston” (2020)

Jeff Pearlman, “Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s” (2013)

Bill Russell with Taylor Branch, “Second Wind: The Memoirs of an Opinionated Man” (1979)

Bill Russell with Bill McSweeney, “Go Up for Glory” (1966)

Bill Russell with Alan Steinberg, “Red and Me: My Coach, My Lifelong Friend” (2009)

Dan Shaughnessy, “Wish It Lasted Forever: Life With the Larry Bird Celtics” (2021)

More to Read

The team

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.