Where ‘one wrong move’ means disaster: Inside the fragile art of ‘Domino Masters’

DeMond Nason discovered domino art after getting his heart broken.

“I was going through YouTube clips trying to find something to comfort a broken soul,” recalled Nason, a San Diego native now based in Brooklyn, N.Y. “I came across these domino drops and there was something just so tranquil about them.”

After expressing his interest in trying dominoes himself on social media, a friend and veteran domino artist reached out to invite Nason to join him.

“There’s a beautiful release to the art form that’s a big pull for me,” said Nason, who has experience performing in Broadway national tours and off-Broadway shows. “Part of [domino] art is the fall, that’s what I love about it. You’re building something, and then you [topple] it over and you move to your next canvas. … I really use the art as a form of mental health, as a form of meditating and releasing the stress.”

“Lego Masters” is Fox’s new competition show about building Lego. But what does being a Lego Master mean?

Now, however, Nason is adding the stress of competition to his dominoes — he’s among the domino artists vying for the top prize in Fox’s “Domino Masters,” a reality competition series premiering Wednesday. Hosted by “Modern Family” alum Eric Stonestreet, the show will see 16 teams of three compete in a tournament for a $100,000 cash prize as well as the title of Domino Masters.

Similar to other creative competitions, each week four teams will be presented with a theme and given a set time to complete their domino builds. Their goal is to use the 16 hours to construct a massive piece to impress the judges: actor and mathematician Danica McKellar, former NFL player and art enthusiast Vernon Davis and professional domino and chain-reaction artist Steve Price.

Unlike most other art forms that are shown in competition shows, dominoes are kinetic. The art is not just in the completed structures that are built but also in the way they topple, or the sequence as the bricks tumble down.

“The difference between dominoes from any other building hobby is that in the end, it moves,” said Michael Fantauzzo, who is competing on the show with his cousin Matt VanVleck and friend Doug Pieschel as team Back Breakers. “It does something completely on its own, relying both on physics and artistry, to make something that’s really unique. There’s just nothing that’s quite like it.”

Both the creative possibilities and the thrill of a successful topple are among the signature elements of the medium that appeals to these domino artists.

“I love the idea that this art isn’t a still frame,” said Emma Renner, a systems engineer who is part of team Brains and Brawn. “The art is in the full journey and process of it. The art starts when you put that first domino down, and then every domino — sometimes it’s 50, sometimes it’s hundreds, sometimes it’s tens of thousands of dominoes you’re putting down for one project — every domino is purposeful.”

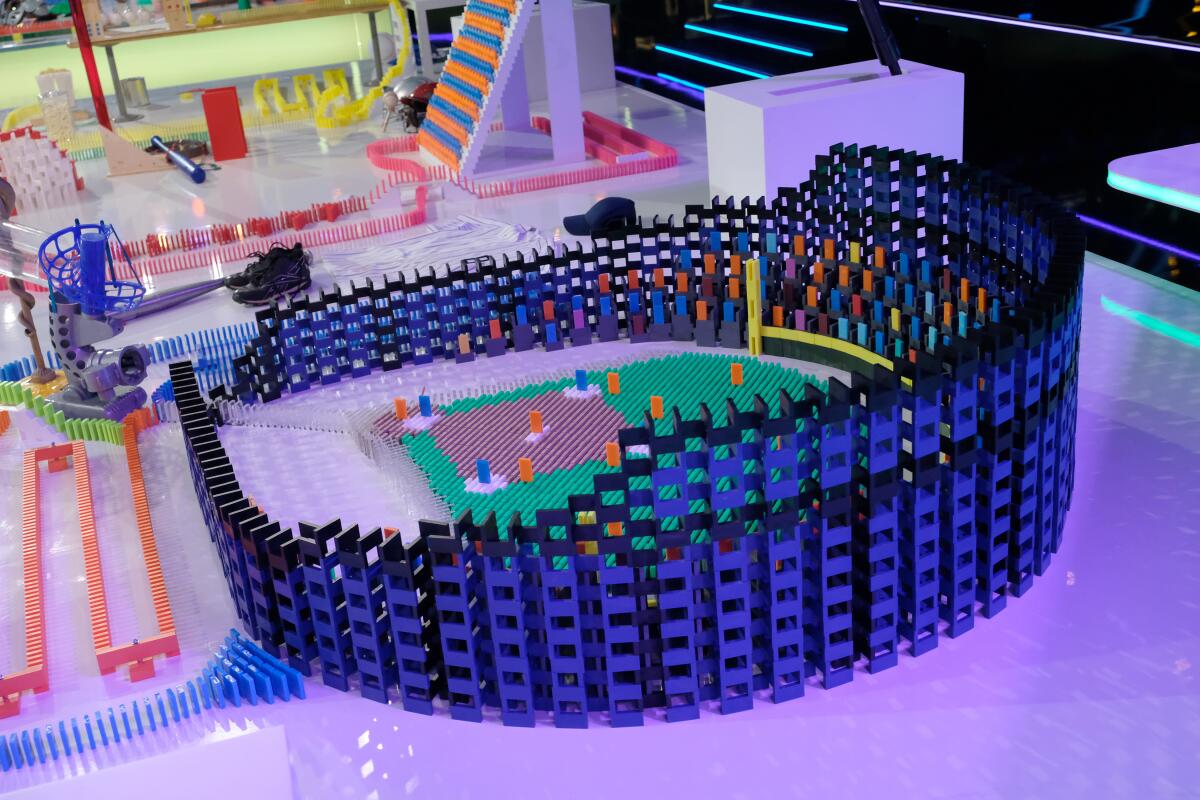

These bigger domino projects are more than just a long line of single-row bricks tumbling over. Complex domino projects, like those showcased in the competition, incorporate techniques like domino fields and walls — which are two-dimensional domino planes created by aligning bricks horizontally on the ground or stacking them vertically, respectively — as well as 3-D structures built from dominoes and other creative chain-reaction tricks.

“Every domino artist has a different style,” said Scott Suko, a veteran domino artist competing with a team named the OG Topplers. “Some people like to do beautiful painting-like patterns on the floor. Other people like to do more Rube Goldberg elements.”

Suko, who first became interested in domino art after watching a world-record-breaking domino topple in 1979, considers himself “an old-school domino toppler” who usually uses mostly wooden dominoes in his projects. (Dominoes made from other materials like plastic are more commonly favored by newer domino artists.)

“I like to connect them to classic wooden toys,” said Suko, whose friend and teammate, Paul Nelson, is the domino artist who invited Nason to his first topple. “I work all sorts of toys and games into [pieces] and make them move under the control of the dominoes. … I really like the back and forth between dominoes falling, old classic wooden toy moving, dominoes going up staircases, something sliding down a zipline, dominoes launching balloons. It’s just one thing after another. It makes it sort of goofy and fun working those types of things into it.”

In addition to different tricks and techniques, however, the judges on the show are looking for stories told through each team’s topples.

“Storytelling was a thing really pushed by the judges,” said Renner. “Not only when it’s just standing, when your creation is done before you’ve toppled it, does it need to be a story, but as it’s falling, the topple of it should add more elements to the story. The sequence should be a story.”

“What’s so great about dominos is you literally have a throughline,” said Nason. “There’s always a beginning, a middle and end. … The dominoes don’t just drop in one big fall. It’s on a path. You’re able to create these wonderful stories through the lines of the dominoes.”

On top of the storytelling elements, resident domino and chain-reaction expert Price said as a judge he “was there to make sure that [the teams] challenged themselves” by using more difficult techniques.

“I was looking for the variety of different types of domino and chain-reaction techniques used, the variety of different sizes,” said Price. He also was on the lookout “for really good combinations of chain-reaction tricks that were directly incorporated into the domino techniques [and] how well [the teams] can mash the two worlds together.”

A domino novice, for example, could be equally impressed by the pixel art of a massive domino field as by a structure built vertically. But as Price explained, “Even though it may contain fewer dominoes total, it’s way more difficult to build because with 3-D structures, if you make one wrong move, the whole thing will fall.”

Price also was looking for ways that teams may have gotten different objects to behave in surprising ways.

Fantauzzo, who first became interested in dominoes when he was 12, also is drawn to the different movements that can be created in the topples.

“Even if you create tons of different pictures, tons of different-looking structures, they’re usually going to fall down the same way,” said Fantauzzo. “But if you’re clever enough with your dominoes, you can make them fall in insane patterns. You [can] have a circle of structures, and then they all fall inward at the exact same time. That creates a very satisfying motion for me.”

Fantauzzo also enjoys crossover fields, in which the art is revealed when the piece’s rows fall in alternating directions.

From “Lego Masters” to “The Great Pottery Throwdown,” the niche reality competition is on the rise. We asked the experts to explain why.

Dominoes are a fragile medium, and although experienced domino artists have tested various reactions and are familiar with different design principles and best practices, a completely successful topple is not guaranteed.

Because the teams are building in close quarters, “When someone’s [project] accidentally topples, it affects everyone in the room,” said Renner. “It’s awful. If you’re testing something and it’s going to sound like a bunch of dominoes falling, you have to yell ‘test’ to everyone so if they hear that noise they don’t automatically freak out and mess up what they’re doing.”

Failures and accidents are part of the learning process for artists like Fantauzzo.

“I film everything,” said Fantauzzo. “I can look back at the scenario and see, ‘OK, why didn’t this work?’ … Paying attention to those fails has made me a better domino artist.”

Even when things don’t go as planned, “It’s just dominoes,” stressed Nason. “The cool thing is that we have more dominoes. We can rebuild it.”

‘Domino Masters’

Where: Fox

When: 9 p.m. Wednesday

Rating: TV-PG-L (may be unsuitable for young children with an advisory for coarse language)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.