‘Star Trek’ is the greatest sci-fi franchise of all. Why it’s stood the test of time

Of all the science fiction franchises in the known universe, the one I would take to a desert island — or planet, I guess — is “Star Trek.”

I am not a Trekkie by any means (not that there’s anything wrong with that). I have never dressed as a Vulcan. I can’t speak a word of Klingon or identify the starships by their silhouettes or tell you how many tribbles it takes to make trouble. But a lot of general knowledge has seeped into my brain over the years: “Beam me up, Scotty.” “Fascinating.” “He’s dead, Jim.” “I’m a doctor, not a [insert any other profession].” “Make it so.” “Engage.” I’m au fait with all those catchphrases. I’ve watched every series, if not in their entirety, and all of the movies. (I do not count the J.J. Abrams big screen reboots, which operate on another timeline, though I’ve seen those too.) And I have greeted each new iteration with interest and a certain “Hello, old friend, what are you up to now?” affection.

This year marks the centenary of creator Gene Roddenberry’s birth and 55 years since the premiere of what is now officially referred to as “The Original Series” or “TOS,” and there are various home video remasterings and reboxings available. Thursday sees the premiere of the excellent “Star Trek: Prodigy,” streaming on Paramount+, where the franchise is star-based. This new CGI series is about a bunch of misfit teenagers escaping a slave-labor camp in a stolen Federation starship, on the run from a very bad guy — but kind of joyriding too. (It’s being advertised as the first “Trek” series aimed at young audiences, somehow forgetting or reclassifying the early 1970s “Star Trek: The Animated Series,” which featured William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy and DeForest Kelley in their original roles as Kirk, Spock and McCoy, aired Saturday mornings, and won a Daytime Emmy as a “children’s series” in 1975.) None of the characters is human or in some cases even humanoid, apart from the hologram of Capt. Janeway (Kate Mulgrew), employed here as a kind of interactive help-bot. It is quite lively in terms of action, and funny where it’s supposed to be, but as in all “Star Trek” series and films, character is what counts most.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

From the name forward, the franchise bears comparison with “Star Wars,” with its spaceships and aliens and interplanetary scope, not to mention the range of storytelling platforms — movies and TV, cartoons and comics, novels and fan fiction.

I wouldn’t deny that there’s fun to be had from George Lucas’ baby, now bouncing for Disney, but “Star Wars” is not science fiction. It’s a fantasy set in space, where wizards do magic and heroes fight with swords and prophesied chosen ones take up their lightsabers; a special effects western cum samurai film cum collection of war movies in which, a few defections notwithstanding, good fights bad until one obliterates the other; and an expensive homage to the cheap Saturday serials of the 1930s. Its one endlessly repeated theme is bad parenting — or, in the case of “The Mandalorian,” the first “Star Wars” live-action television series, good (surrogate) parenting. But “Star Wars” on the whole has no real interest in ideas, in asking “Why?” or “What if?” The droids are comic relief, and slaves. Joseph Campbell’s the Hero with a Thousand Faces has often been cited, by Lucas and others, to connect these characters to a deeper storytelling tradition; the problem with a thousand-faced hero, however, is that you have seen that shtick a thousand times.

“Star Trek” is a different animal. From the beginning it had a mission, not just to explore strange new worlds, seek out new life and new civilizations, and boldly go where no earthlings had gone before, but to model a future for its audience that was a little ahead of its time. Where “Star Wars” was slow off the mark with diversity — the only Black actor in “A New Hope,” James Earl Jones, supplied the voice of a white character, and even now has only managed one same-sex kiss between minor characters — “Star Trek” made diversity a point from the beginning, with George Takei’s Sulu and Nichelle Nichols’ Uhura on the bridge. (Whether the 1968 kiss between Kirk and Uhura was the first interracial kiss on television is a subject of debate and semantics, but it was in any case ahead of its time.) The third series, “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine,” put a Black man (Avery Brooks’ Sisko) in charge; the next, “Star Trek: Voyager,” a woman (Mulgrew’s Janeway). Throughout the various series, and in the sci-fi tradition, contemporary earthly issues — racism, Cold War politics, environmental degradation, despotism, sexism — are seen through the lens of future, extraterrestrial exploits. The presence of aliens (also ethnically diverse), on the crew or just passing through, offered writers a chance to comment with distance on the puzzlements of human behavior.

Nichelle Nichols, the beloved Lt. Uhura on ‘Star Trek,’ is living with dementia and struggling financially. Three parties fight to control her fate.

That “Star Trek,” which originally ran from from 1966 to 1969, returned to television in the first place — there was a nearly 20-year break before “Star Trek: The Next Generation” — owes something to “Star Wars,” of course, which made space operas eminently bankable. But it had plenty of firepower of its own, charged by the the post-cancellation success of the original series, which flourished in syndication. A 1975 “Star Trek” convention in New York City, two years before “Star Wars” premiered, reportedly drew a crowd of 15,000 and turned thousands more away at the door; by 1986, the year before “The Next Generation” premiered, it was the most successful syndicated series going. A big-screen franchise, eventually numbering six films with the original crew, was up and running by 1979, followed by four “Next Generation” films — the first of which paired Shatner’s Kirk and Patrick Stewart’s Picard in a timeless corner of space.

To be sure, the revival of the brand may also be seen as a bottom-line event, designed to bring subscribers to what was then known as CBS All Access and is now called Paramount+, much as “The Mandalorian” was a boon to Disney+.

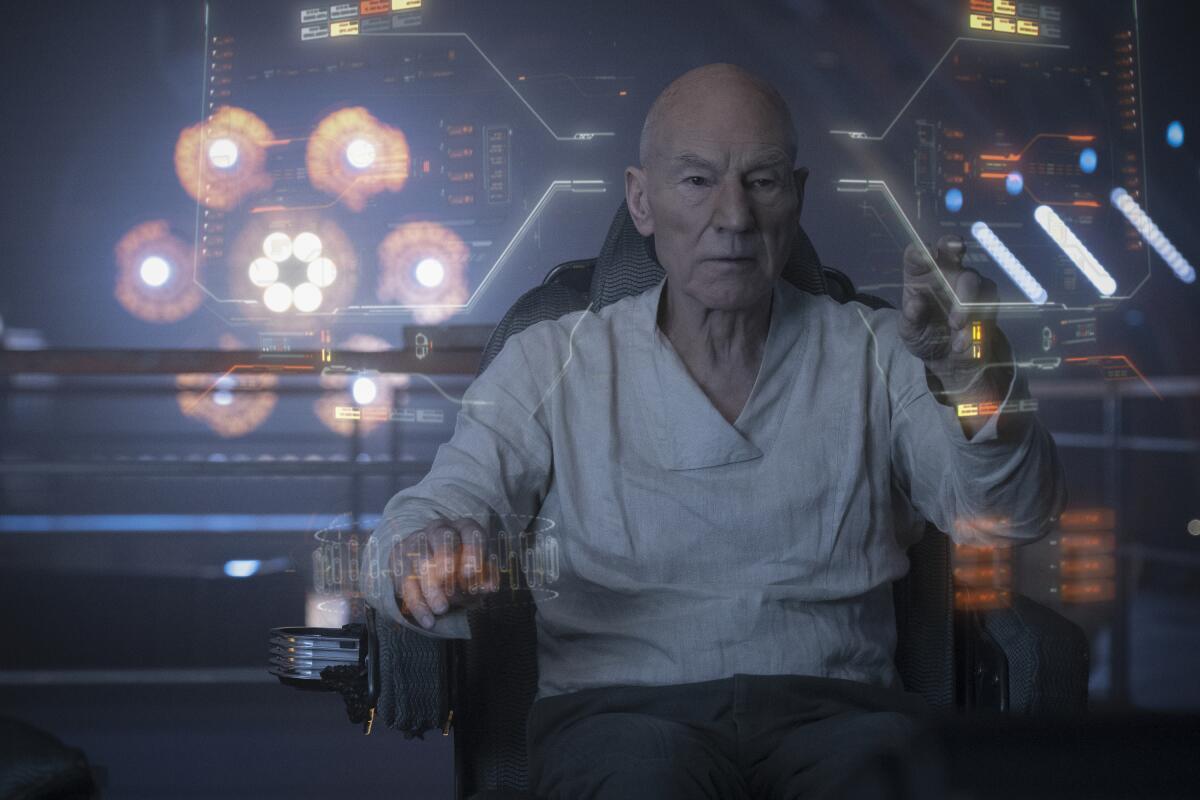

But it has produced excellent results. I’m a fan of all these shows: “Star Trek: Discovery,” especially in its adventuresome second and third seasons, with a fourth season premiering Nov. 18; the deep and thoughtful “Star Trek: Picard,” with Stewart back in the saddle (though going rogue); “Star Trek: Lower Decks,” an adult cartoon about service workers on a “second contact” vessel, that both parodies and celebrates the spirit and story conventions of the live-action shows while adding quotidian context and details. (We see how the ordinary crew lives; I can’t tell if it’s canonical, but it should be.) And there are more “Treks” arriving: the aforementioned “Prodigy”; “Star Trek: Strange New Worlds,” a spinoff at once from the second season of “Discovery” and the original “Star Trek” pilot, with Ethan Peck as a well-cast young Spock, Anson Mount as Capt. Christopher Pike and Rebecca Romijn as his Number One; and when one of the current series departs and other stars align, “Star Trek: Section 31,” another “Discovery” spinoff, with Michelle Yeoh reprising her role as Philippa Georgiou.

Because it was born and grew up on television, in an age when special effects were a luxury and not a given, the franchise has been devoted less to action than talk, and to philosophical questions — what it means to be human, or Vulcan, or Klingon, an android or noncorporeal. The fact that there are many, many, many hours of “Star Trek” content — which are, to some extent, preserved in the new series, with their intersecting plotlines — means that “Star Trek” has had the space to tell many sorts of stories: mystery stories, love stories (and impossible-love stories), funny stories, family stories, spy stories, horror stories, workplace stories. Much of the charm in the original series derives from the double act Shatner and Nimoy developed, based in a kind of affectionate mutual incompatibility, and subsequent “Treks” developed bonds between characters it is easy to invest in, and which in some cases (as with Capt. Picard and Data) became their very foundation.

It’s an emotional show, and not infrequently a show about having emotions — giving in to them, repressing them, making use of them. On the one hand you’ve got Spock, and all the Vulcans who came after, pumping for logic; on the other, there’s Data the android, a logical being who dearly wants to know what it is to be human, like his friends. It’s significant that the second series, “The Next Generation,” added a therapist to the crew — Marina Sirtis’ Deanna Troi — and eventually a bartender (Whoopi Goldberg as Guinan), which is to say, another sort of therapist.

The original series could be incredibly silly, unwittingly (and sometimes wittingly) self-parodying. The lack of money, one might say, was on the screen. One could practically smell the gray paint and plywood on the Enterprise sets. The series’ celebrated technobabble is just a kind of reformulated abracadabra; human characters get the hang of alien gear faster than you could look up how to reset your car’s clock in the owner’s manual. Everything happens in the nick of time. Kirk’s occasional romantic interludes might have seemed kind of hilarious even at the time, but certainly are risible now; and although there were strong roles written for women from the beginning, they were often stuck in some sort of minidress.

It was 50 years ago that “Star Trek” died.

And despite their hopeful tenor, these shows’ creation was not always peaceable. Roddenberry, whose involvement was lesser and greater over the years for reasons of health or business, could be critical of “Trek” made under others’ watch if he felt they weren’t staying true to his big themes. (Wikipedia will give you a pretty good idea of the rough roads some series and films have taken on the way to launch, and after.) But taken as a whole over time, “Star Trek” has remained remarkably true to a vision: Peace is better than war; violence is dramatically less interesting than discussion; difference is not merely respected but portrayed as a positive good.

There is the convention of the disposable crewman (“redshirts,” referring to the color of their uniform, has become a generic term for an anonymous character who dies early in a scene to indicate danger), but death even of the nameless is not usually paid back with death; revenge, while it is a motivating factor for characters in many stories, is regarded in the “Trek” universe as a dish best not served at all.

Mighty heroes mowing down hordes of literally faceless enemies, crowds cheering military victories — that is not the “Star Trek” style. There is relief when a foe is sent packing, but rarely glee. Phasers are usually set to stun. Spock’s Vulcan nerve pinch can send an opponent to the floor, but the Vulcan death grip (“The Enterprise Incident,” Season 3) is a fiction, a subterfuge. Current custom and affordable, high-quality modern SFX technology does mean that there is more space battling in the new “Treks” and more martial arts-style fighting (you are not going to leave Yeoh sitting in a chair, after all), but diplomacy remains the goal, and it is only when that fails that big things are blown up. “Get us out of here” is a thing Capt. Kirk would regularly say.

“Star Trek” envisions an Earth in which, as in John Lennon’s “Imagine,” the old dividing lines — ethnic, political, religious — have all disappeared; there is no war, no poverty, no pollution, and technology finally works for us rather than against us. Though these things seemed possible in the progressive era when “Star Trek” was born, I’ve grown increasingly doubtful about humanity’s ability to intelligently regulate its most local affairs, let alone join with alien species in a project of interplanetary goodwill.

Which may be why I love the “Star Trek” universe, and why I melt when, at the end of the third season of “Discovery” — a season very much about coming to terms with one’s nature and needs, limits and abilities — Sonequa Martin-Green’s (newly promoted) Capt. Burnham says, “The need to connect is at our core as sentient beings. It takes time effort and understanding … but if we work at it a miracle can happen.”

And who knows? The future is a long road.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.