Why press-averse Naomi Osaka agreed to let Netflix make a docuseries about her life

It was Naomi Osaka’s idea to have cameras trail her and make a documentary series about her life.

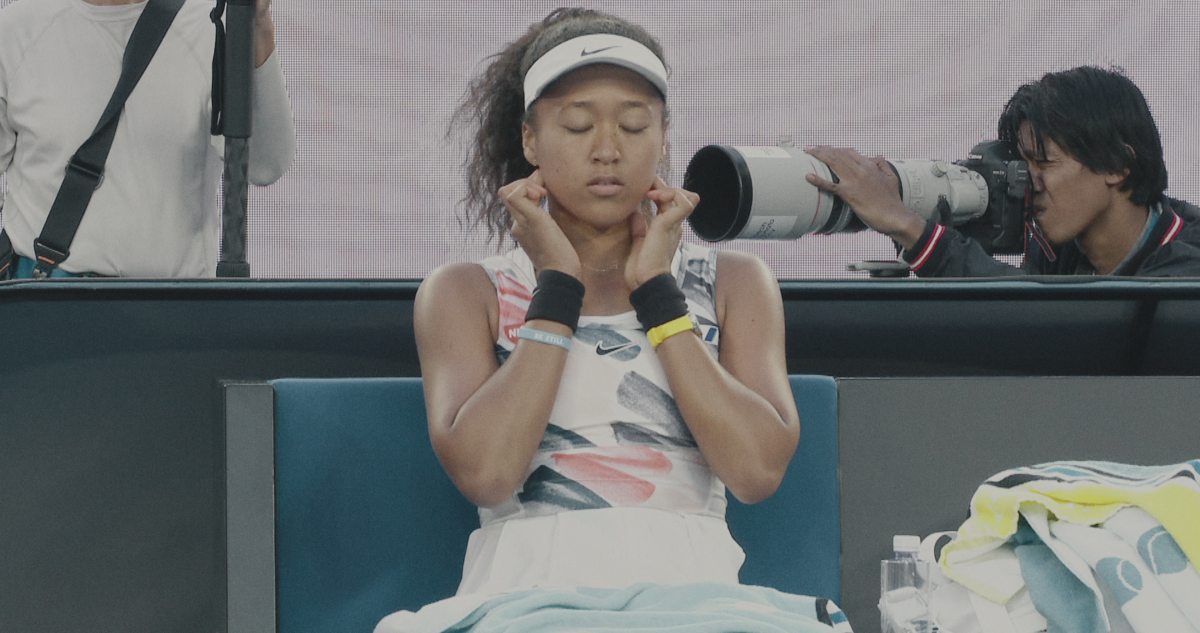

That may come as a surprise to anyone who has been following sports headlines of late. In May, the 23-year-old tennis star was fined $15,000 by French Open officials after she pulled out of post-match press conferences. She said the experience of being asked repetitive questions, or ones that brought “doubt” into her mind, was taking a toll on her mental health. When the tournament responded by threatening her with further financial penalties or suspension if she continued to “ignore her media obligations,” she withdrew from the competition altogether. In June, she nixed plans to play at Wimbledon as well.

But “she was the one who wanted to tell her story” in the new three-part Netflix series, insisted Jamal Henderson, one of the project’s executive producers. (Osaka and her family are not doing press to promote the project.)

The newsworthy tennis phenom is the subject of an atmospheric Netflix docuseries. It will leave you feeling as though you’ve gotten to know her.

Per Henderson, Osaka and her team began discussions about creating a documentary or podcast with the SpringHill Company — LeBron James’ development and production enterprise — back in 2019.

“She was still very much on the come-up — she’d won a couple of majors, but wasn’t where she is now where you can get a Sweetgreen bowl with her name on it,” said Henderson, who serves as chief content officer at the Lakers player’s company. “We all decided that the best idea was to make something that documented her life and what it feels like to be the contender who beats Serena [Williams] and has all this pressure about being the next up.”

When Henderson floated the idea of an Osaka doc to Netflix, which had a preexisting relationship with SpringHill, he said the streamer suggested the athlete take a meeting with Garrett Bradley. Even though the young filmmaker had yet to earn an Oscar nomination for her documentary “Time,” “Netflix had been tracking her like everybody else and knew she was obviously on the rise,” Henderson recalled.

Like with “Time” — the story of a mother trying to free her husband from a 60-year prison sentence — the idea with “Naomi Osaka,” which premiered on Friday, was to avoid sit-down interviews with its subject or other talking heads. SpringHill helped Bradley secure access to roam with her camera around prestigious tournaments like the U.S. Open. Osaka’s parents — the Haitian Leonard Francois and Japanese Tamaki Osaka — handed over years’ worth of footage from their home video archive to the documentarian. And Naomi Osaka never established any restrictive ground rules, allowing Bradley to film until she felt the project reached its natural conclusion — a process that ultimately spanned two years.

The athlete and the filmmaker first met at the 2019 U.S. Open. Bradley had never made a movie with someone she didn’t have a prior relationship with, and said she was initially “out of [her] comfort zone” working with someone she didn’t know. But over the course of a day together in Queens, New York, Bradley shared her vision with Osaka. Because the tennis player was barely an adult, Bradley said she was wary of attempting to create a definitive portrait of her. Instead, she wanted the series to be a coming-of-age story without a linear structure — taking a verite approach and avoiding “recapping a chronology we could just read on Wikipedia.”

That day, Bradley “just went with [Osaka] wherever she needed to go”: press junkets, car rides, dinners. Her intention was to get a sense of how the athlete moved through her space, but she also quickly realized how much a tennis player’s headspace informs her play.

“Tennis is a mental sport, so it’s a sport of solitude, in a sense,” said Bradley. “That was something I needed to be aware of — that I’d have to be around her without demanding a lot of conversation. It was a lot of energy work.”

In conversation with The Times, Bradley spoke about a journey that took her and the athlete to New York Fashion Week, a Black Lives Matter protest, the Australian Open and Haiti, where Osaka’s father was raised.

L.A. Times columnists Helene Elliott, LZ Granderson, Dylan Hernández and Bill Plaschke discuss Naomi Osaka, the role of media, athletes’ mental health and more.

Why do you think Naomi was open to making a docuseries when she’s generally reluctant to share herself with the media?

I think that part of making a film with somebody, regardless of who they are, is that you’re really with them. And the role of press, in her world, is not there to be with her. They’re there to look at her and, in the worst scenarios, project on her. I tried to reinforce that I wasn’t press as much as possible, even in terms of physically where I was. It was important that I was seeing what she was seeing — to show her looking at the press, for instance. In many ways, I think this shows the building blocks to the current moment of where we’re at. She was in contemplation, figuring things out, but she has a very clear perspective at this point.

Did she tell you that there were going to be moments before big tournaments where she was going to need time away from the cameras?

We didn’t create any ground rules, per se, and I actually didn’t overthink it too much. ... There’s a balance you play in making a documentary of what’s really worth it. Is it more worth it to capture something, or to support a person? First and foremost, I care about the people I’m working with, so I make decisions based on my own empathy and instinct at any given moment. I think that might be a controversial thing to say as a director, but it’s always the way I work. There were moments where being there without a camera was important. And also why having her own camera was important to what she needed in her own journey.

Yes, in some of her most personal moments in the series, like in the wake of her mentor Kobe Bryant’s death, Naomi is filming herself.

A lot of it certainly had to do with the pandemic, but I also had just finished a film that was really centered around a woman who had been self-recording for 21 years. Something I really took away from that process was that the narrative will be created for you if you are not in charge of your own. What does that have to do with the Black family archive? I wanted to give Naomi something for herself that hopefully she can carry on. It’s totally for her, and it will continue to gain meaning as she moves through the world.

There is a lot of footage of her at tennis press conferences. Did you pick up on the fact that she was not enjoying those experiences at the time?

When I was sitting in those rooms with her filming the press themselves, I could completely empathize with what she was going through. But I also thought that she has always been very strong in those circumstances. When she does speak, she’s incredibly clear and incredibly to the point. She speaks profoundly with fewer words than most of us are able to. I think anxiety is something she has identified for herself in the past few weeks. ... I’m not sure she would have articulated it as anxiety at that moment. It takes time to get to that place. And it also takes time to build strength and decide how to use your voice.

Naomi has gained a reputation for being shy or soft-spoken. Do you think that’s fair?

I think we have different perceptions and a different set of projections that we put on women — and Black women — in the public sphere. She is an incredible leader of her generation in that she is really choosing how and when she wants to use her voice. I think that’s a sign of power, more than vulnerability. It doesn’t mean she doesn’t have anything to say, or that she doesn’t ever smile. It means she’s choosing when she wants to.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.