How ‘The Real Housewives’ glam arms race gets its cast into hot water

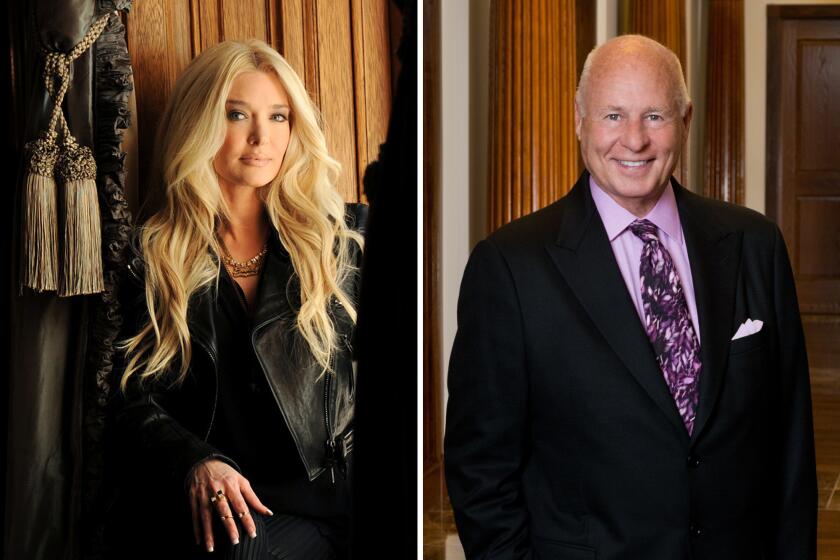

If you know anything about Erika Girardi, the “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star who performs dance music under the name Erika Jayne, it’s probably that she likes to spend money.

In case you missed the pair of private planes or the team of stylists that travel with her around the world, there’s the music video where she sings, “It’s expensive to be me/ Looking this good don’t come for free” while frolicking on a bed piled with cash.

She always had reason to brag, or so it seemed: She was married to Tom Girardi, a renowned trial lawyer who made millions by suing corporate behemoths on behalf of regular people. If she used some of his vast fortune to fund her music career and finagle a starring role on Broadway, so what?

But during a recent episode of “Beverly Hills,” Erika Girardi may have finally given up the game, telling a castmate: “My whole life is smoke and mirrors.”

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

The comments were recorded last fall, days before Girardi, 49, abruptly filed for divorce from her much older husband after two decades of marriage. Bravo fans were shocked, but as The Times reported, Tom Girardi’s storied career was in ruins amid allegations that he’d embezzled millions of dollars from bereaved clients and used it to maintain an extravagant lifestyle.

Erika Girardi now faces scrutiny over her possible involvement in the scandal and the impression that money intended for “orphans and widows” was frittered away on her celebrity ambitions. So far, the singer seems undaunted by the criticism, posting defiant memes and glamorous red carpet shots on her Instagram account.

The saga, the heavily hyped focal point of the current season of “Beverly Hills,” makes Girardi the latest of the “Real Housewives” to contend with legal and financial difficulties connected to the fabulous persona they convey on TV. In March, “Salt Lake City” housewife Jen Shah was arrested on suspicion of running a vast telemarketing scheme targeting the elderly. “New Jersey’s” Teresa Giudice spent nearly a year in prison on multiple fraud charges.

And although only a few “Housewives” have been implicated in such brazen white-collar crimes, the list of bankruptcies, foreclosures, tax liens and lawsuits involving cast members runs longer than Girardi’s hair extensions.

Since the inception of “Real Housewives,” the sort of “smoke and mirrors” Girardi described have been central to the show — and, arguably, one of the keys to its success.

Bankruptcy trustees have accused the reality star of concealing assets for her husband and are dispatching investigators to comb through her belongings and accounts.

‘At least I’m not going to jail’

The franchise’s first property, “The Real Housewives of Orange County,” premiered in 2006, at the height of the real estate bubble — then exploded into a pop culture phenomenon during the Great Recession, morphing along the way into an orgy of competitive consumption. Women on the show are implicitly encouraged to overextend themselves by producers who reward ostentatious and frequently irresponsible behavior with screen time and juicy story arcs.

Sometimes the investment pays off. “New York’s” Bethenny Frankel parlayed reality TV stardom into a $100-million cocktail brand. “Atlanta’s” NeNe Leakes charmed her way into an acting career. Those who live the largest and spend the most lavishly — whether on a new house, a new purse or a new nose — often amass a following, which in the world of reality TV is a form of power: greater leverage when negotiating contracts between seasons and free publicity for whatever low-calorie cocktail or handbag line they are, inevitably, hawking on the side.

“Real Housewives’” prime location in the attention economy cuts both ways, though: At some point, viewers — and law enforcement — may begin to wonder, “Just where is all this money coming from?”

“These women are thinking of themselves as cast members with a storyline,” says Racquel Gates, associate professor of media and cinema studies at the CUNY College of Staten Island and an avid “Housewives” viewer from Day 1. “If your life is not interesting enough in all the ways the show defines interesting, you lose your paycheck. You get fired. That’s a very real pressure.”

Gates cites “Beverly Hills” housewife Taylor Armstrong, who threw a widely mocked $60,000 birthday party for her 4-year-old daughter in the show’s first season. Yes, it was ridiculous, but, Gates says, “Taylor isn’t just throwing a birthday party, Taylor is throwing a birthday party that is going to be a filmed event.”

From the beginning, “Real Housewives” has called attention to these lavish expenditures with sly editing and on-screen graphics listing the cost of various purchases — all part of the “Bravo wink,” the house style designed to stir both envy and disdain in the audience.

In the early years, though, “Orange County” was about more than just our Bush-era fascination with the region’s Hummer-driving nouveau riche. Set in the affluent planned community of Coto de Caza, the series followed a group of loosely acquainted women — some haves, some have-nots — as they balanced work, family and the pressure to conform to the O.C.’s blond, surgically enhanced beauty standard. One, Lauri Waring, was a single mom who moved out of a Coto McMansion and into a cramped town house after a bitter divorce.

But the pressure to deliver a compelling storyline ultimately contributed to financial ruin: Lynne Curtin joined “Orange County” in its fourth season with a mostly forgettable arc about her embellished cuff business. Then she and one of her teenage daughters decided to get plastic surgery on the show. “I don’t put a price tag on my wife and children’s happiness,” said her husband, Frank.

A few episodes later, Curtin’s daughters were at home alone when the family was served with an eviction notice. (One of the girls called her parents to break the news, shielding her face with an extended middle finger pointed at the Bravo cameras.)

“The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City” adds a novel ingredient — Mormonism — to the usual pettiness, plastic surgery and conspicuous consumption.

When the global economic crisis arrived, though, the “Real Housewives” bubble only inflated: Between March 2008 and May 2009 — a period when the unemployment rate nearly doubled — the franchise expanded to three new locations (New York, Atlanta and New Jersey). A short-lived D.C. version debuted in mid-2010 but was canceled after two financially troubled cast members crashed a White House dinner, their social ambitions triggering a national security freakout. A Beverly Hills edition, featuring the most eye-popping real estate to date, followed later that year.

As millions of Americans were mired in economic despair, investigating the “Housewives’” perilous finances became a cherished cultural pastime, the subject of countless blog posts with headlines like, “4 out of 5 Real Housewives of Atlanta are Actually Broke.”

Viewers enjoy watching these women get into trouble, says Nicole B. Cox, an associate professor of mass media at Valdosta State University in Georgia who has conducted scholarly research on “The Real Housewives.” “We’re disgusted by them, and we feel superior, because it’s like, ‘I might not be able to buy those Chanel earrings, but at least I’m not going to jail.’”

‘I hear the economy’s crashing, so that’s why I pay cash’

The schadenfreude that marks the “Real Housewives” fandom occasionally comes up against real tragedy. When Armstrong’s estranged husband, Russell, died by suicide in 2011, reports emerged that he was deeply in debt. “He was living month to month to support his lifestyle for Taylor,” claimed his lawyer. Bravo ignored calls to cancel the series, and Armstrong remained in the cast for two additional seasons.

More frequently, as in the case of “New Jersey’s” Teresa Giudice, the conspicuous consumption crucial to the franchise’s formula casts a very public spotlight on the family finances.

Few “Housewives” have aroused suspicion as immediately or intensely as Giudice: Minutes into the very first episode of “New Jersey,” she spent $120,000 on furniture. “I hear the economy’s crashing, so that’s why I pay cash,” she said of the purchase, meant for the 10,000-square-foot faux French Chateau outfitted in marble, granite and onyx that she and her husband, Joe, spent three years building. The source of all this cash was murky: Joe, supposedly a successful entrepreneur, ran a construction company out of a modest storefront.

“Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” stars Kyle Richards, Erika Girardi, Lisa Rinna, Denise Richards, Dorit Kemsley and more talk quarantine and Season 10 drama.

The show was an instant sensation when it debuted that year, thanks largely to Teresa’s attention-grabbing shopping sprees and now-legendary table-flipping tantrums. But the ruse came to an end in 2013, when the Giudices were indicted on 39 counts of fraud. According to the U.S. attorney, the couple had lied to lenders about their income to obtain mortgage loans: In 2009, the year of that furniture-buying binge, they’d filed for bankruptcy, intentionally concealing income earned from the TV show and other deals capitalizing on their sudden celebrity.

After striking a plea deal, Joe went to jail for 41 months and was deported to Italy, the country of his birth. Now divorced, Teresa leveraged her prison stint into multiple memoirs and a spinoff, and continues to downplay her role in the fraud. If anything, her brush with the law has cemented her status in the Bravo firmament: She is the only original cast member remaining on “New Jersey” and will soon star in a “Real Housewives All-Stars” series for Peacock, NBCUniversal’s streaming service.

‘Nefarious pleasure’

Girardi’s arrival on “Beverly Hills” in the show’s sixth season marked the beginning of what could only be described as a “glam” arms race. The women of “Beverly Hills” — never exactly low-maintenance — scrambled to keep up with Girardi, who turned up to film in increasingly theatrical couture looks and boasted of dropping $40,000 a month on hair, makeup and clothing. The pressure to keep pace with Girardi has inspired petty arguments and such relentless one-upmanship that beaded, floor-length gowns are now considered reasonable barbecue attire.

In similar fashion, “The Real Housewives of Atlanta” — a show about “bourgeoisie housing anxiety,” as critic Niela Orr wrote for Buzzfeed — was consumed by the cold war between Kenya Moore and Sheree Whitfield as they built rival McMansions. “Salt Lake City’s” Shah emerged as the breakout star of the series, which premiered in November, after ordering her team of eight assistants around during preparations for an extravagant party at the (probably rented) home in Park City, Utah, she dubbed the “Shah Ski Chalet.” Like Girardi, she had stylists perpetually on call. Sure, no one understood what she actually did for a living, but that merely added to the head-scratching spectacle.

That authorities are paying close attention to what the rest of us might wave off as a guilty pleasure is evident from the U.S. attorney’s statement detailing charges against Shah — “who portrays herself as a wealthy and successful businessperson on ‘reality’ television” — and her TV assistant, Stuart Smith. “Shah and Smith flaunted their lavish lifestyle to the public as a symbol of their ‘success,’” it read. “In reality, they allegedly built their opulent lifestyle at the expense of vulnerable, often elderly, working-class people.” (The role Girardi’s TV stardom may have played in her husband’s downfall remains unclear, but at least one lender has accused the Girardis of inappropriately using money “to maintain their glamorous public image.”)

Shah’s legal trouble has done little to harm her standing at Bravo. Cameras were reportedly rolling when she was arrested in March because, as one source told US Weekly, “Production sees this as a great story line.”

Of course, our ideas about wealth — who has it, who deserves it, whose displays of it are tasteful and whose are gauche — are inextricable from gender and race. The “nefarious pleasure” we take in participants’ rise and fall isn’t neutral, Gates says: Women like Shah, a Muslim convert of Tongan and Hawaiian descent married to a Black man; Giudice, a brash Italian American; and Girardi, a former exotic dancer, receive more scrutiny because they defy the WASP-y ideal of a wealthy person.

In the end, though, Gates doesn’t blame Bravo for our obsession with the lifestyles of the (supposedly) rich and famous, or reality stars deluded into thinking they can fake it ’til they make it. She blames American capitalism. “That’s why we read ‘The Great Gatsby’ in high school. That’s why Elon Musk just hosted ‘Saturday Night Live.’ And that’s why we had the president we just had,” she says. “America has an obsession with wealth and not often enough of an obsession with how one gets that wealth.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.