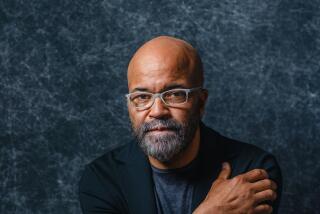

Making a TV show about slavery could undo you. Unless the director steps up like this

Barry Jenkins vividly recalls the moment he first heard about the Underground Railroad.

“I was around 5 or 6, and when I first heard those words, it wasn’t even imagined — I saw Black people on trains that were underground,” he recalled. “My grandfather was a longshoreman, and he would go to work with his hard hat and tool belt. I imagined someone like him building the Underground Railroad. The feeling was beautiful because it was purely about Black people, this idea of building things.”

The youngster would eventually learn that “Underground Railroad” was actually a colorful term for a network of safe houses and routes utilized by slaves to escape their oppressive masters in the antebellum South. But the image stayed with him into adulthood as his films, including the Oscar-winning “Moonlight” and the romantic drama “If Beale Street Could Talk,” made him one of Hollywood’s most respected filmmakers.

Jenkins brings his childhood vision of the railroad full circle with the highly anticipated “The Underground Railroad,” Amazon’s limited series based on Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning historical novel about a runway slave named Cora (Thuso Mbedu) and her desperate, often hellish quest for freedom as she flees the shackles of bondage.

“Them,” about a Black family fighting racism and supernatural forces in the 1950s, includes warnings about its graphic depictions of racist violence.

Whitehead reimagines the Underground Railroad as a boxcar powered by a steam locomotive transporting slaves to free states through subterranean tunnels. The author is an executive producer on the adaptation, which premieres Friday on the streaming service.

The drama marks another high-profile touchstone for Jenkins, who won an adapted screenplay Oscar along with Tarell Alvin McCraney for “Moonlight.” He was nominated for best director for the 2016 gay coming-of-age drama, which won the Oscar for best picture.

Buzz about the project has been building for months. But while Jenkins is obviously proud about his achievement, he also realizes “The Underground Railroad” represents the biggest risk of his career. It’s a series his friends warned him not to make.

The filmmaker is bracing for what he anticipates will be a heightened emotional response to the troubling material, particularly from Black viewers. Early positive reviews have brought him little comfort.

“That’s not what it’s about,” he said in an interview from his house, conducted via video conference, in which he was both energetic and quietly thoughtful. “I know that people are going to encounter these images of my ancestors. This has been the work of the last 4½ years of my life. That responsibility, that weight is still with me. I don’t know how to process that. I used to think that creating the work exorcised those demons or that weight. With this one, it’s not the case. It’s just too much.”

On one hand, Jenkins sees the project as his destiny. Whitehead’s novel affected him deeply, especially when he came across the railroad description: “That gut feeling that I had as a child hit me again when I read the book. Right away I saw it. I said, ‘I have to do this.’”

And he got to see the physical realization of his early vision with the building of an underground set at the Georgia State Railroad Museum in Savannah, Ga.

“I didn’t want CGI for the trains and tunnels,” said Jenkins. “It has to be real. I want the audience to see what I saw as a child. It’s so important that the actors can walk into a tunnel and they can get down on their knees and touch the rails. Can you imagine what my ancestors would have felt if they walked into one of these tunnels and they saw the track and the light approaching and a Black conductor shouting, ‘All aboard!’ It would have been mind-shattering. I wanted to create that.”

But while his poetic and lyrical style in dealing with racial themes in “Moonlight” and “If Beale Street Could Talk” was embraced by critics and audiences, “The Underground Railroad” explores more explosive terrain, diving headfirst into the fiery issue of race and the resulting tensions that have sparked volatile protests across the country and spirited discourse within popular culture.

In Barry Jenkins’ hands, the enslaved emerge as the ancestors they are: We can sit with their pain because he is invested in them. And so are we.

The series is the latest in the stream of noteworthy projects that have mashed up America’s horrific history of race relations with genre elements.

HBO’s “Watchmen” and “Lovecraft Country,” Hulu’s “Antebellum,” Amazon’s anthology series “Them” and the recent live-action short Oscar winner “Two Distant Strangers” all feature explicitly violent scenes of Black people being killed, tortured and brutalized by whites. “Them” and “Two Distant Strangers” in particular have been criticized by Black viewers who label the upsetting images “Black trauma porn.” They claim the scenarios are especially disturbing due to their resonances with real-life police brutality against Black people and the troubling resurgence of white supremacist groups.

The first episode of “The Underground Railroad” is likely to add more fuel to the debate. The installment contains a scene in which a runaway slave who has been captured is viciously whipped in front of horrified slaves and entertained whites before being set on fire.

Black viewers were already weighing in weeks before the premiere, Jenkins says. “When the trailer of the show was released, man alive, a lot of people came after me. The question was, ‘Do we need more images of this?’”

He was cautioned early on that he was stepping into a minefield.

“In the polling of my friends, they said, ‘I don’t think you should make this show. I don’t think the world is ready for this,’” Jenkins said. “But I don’t think the country will ever be ready to look at images from this time. And yet, all you’ve heard for four years was ‘Make America Great Again.’ In hearing that, there has got to be some element of willful ignorance or erasure of all of the things that America has done, particularly when it comes to people who look like me. So if not now, when?”

Jenkins is encouraging viewers to see beyond the depictions of violence to recognize his true objective: to put a spotlight on the triumph of slaves rather than focusing on their trauma. “I have to show the truth of what they went through,” he says, but he also wants to concentrate on the sacrifices the enslaved made as part of “the choice to live.”

“We’ve been shirking the responsibility of honoring these folks for so long, and it’s time for people who work with visual images to honor their sacrifice in living, not dying,” he said. “It’s the sole reason that someone like me is here today. If I can take these images and recontextualize them, it makes the representation of the images worthwhile.”

Amazon’s ‘Them’ and Oscar nominee ‘Two Distant Strangers,’ which mix racist violence and genre elements, have ignited a debate over ‘trauma porn.’

He noted the heavy presence of children in Whitehead’s novel, and said he wanted to mirror that presence in the series.

“Here’s one wonderful thing that Colson did,” he said. “There are authors who struggle with the moral and ethical dilemma of the re-creation of images from that time period. But there is a lot also that has to do with parenting. There are children everywhere in the book. So in our show, children are always around. It came to me [that] two decades after the events of the novel, there are Black men in the halls of Congress. Forty years later, W.E.B. Dubois start[ed] [the Crisis] magazine and the NAACP.”

He paused for emphasis. “I realized that this was one of the greatest acts of collective parenting the world has ever seen. They protected the children. So in the book there is the root of recontextualizing my ancestors. We hear that Black families have always been fractured, and that Black fathers have always been absentee. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

During the shooting of the series, Jenkins gave the cast and crew a clear directive: “I told them, ‘We’re not going to levitate but we are going to find a way to make magic, the same way our ancestors did.’”

In order to ensure a safe and open environment for the handling of the difficult, often visceral subject matter, he recruited Kim Whyte, a mental health counselor based in Georgia. Whyte has provided counseling services and support for the military, schools and community groups.

Said Jenkins of Whyte’s involvement, “I didn’t want these images, even as we were unpacking them, to unpack us.”

Whyte said she was grateful for the trust Jenkins gave her: “I couldn’t find a model before me in terms of being a mental health counselor on a set. Barry allowed me to interact with everyone on the set. He didn’t put up any barriers and he encouraged everyone to utilize me. He allowed me to interact with them after takes, in between takes.”

She said her experience was enlightening. “They were dealing with this emotionally challenging subject matter, and everyone was processing it. Each person had their own unique way that they were dealing with the material. But they all had lives. There were babies being born, they had deaths in their families, they had relationships. But they were also reacting to the material.

“It was just them, trusting us, trusting Barry, trusting themselves, trusting me, trusting each other. We were a family, all working together.”

There were instances where some of the actors who were playing racists had difficulty dealing with their characters.

Said Whyte: “It’s a shared stain against humanity. People would come up to me and say, ‘I have to portray this. How do I explain this to my mom? I don’t like this character.’ Sometimes they would have to unpack those feelings they would have to portray. A couple of people felt they shouldn’t feel a certain way, that the feeling belonged to the Black crew and the Black actors, that they shouldn’t be upset. As we worked through it, I said, ‘Yes, you have every right to be upset about this. It was a crime against Black people, yes, but it was a crime against humanity. And you are human.’ They had to understand it wasn’t their anger.”

When the show premieres, Jenkins is planning to get out of town and detach “in a cabin in the woods for a few days. Then I’ll come back and face the tidal wave.” He added with a smile that working on “The Underground Railroad” “probably took 6½ months off my life. I really think my obit will come out six months earlier than it should.

“But it was worth it.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.