Thanking your therapist in a virtual Emmys speech amid a pandemic? That’s peak 2020

The 72nd Emmy Awards on Sunday captured the spirit of 2020 in two key moments: Jennifer Aniston’s literal dumpster fire onstage and “Watchmen” writer Cord Jefferson‘s shout-out to his therapist in his acceptance speech.

“Thank you to my therapist, Ian,” Jefferson said. “I am a different man than I was two years ago. I love you. You have changed my life in many ways. Therapy should be free in this country.”

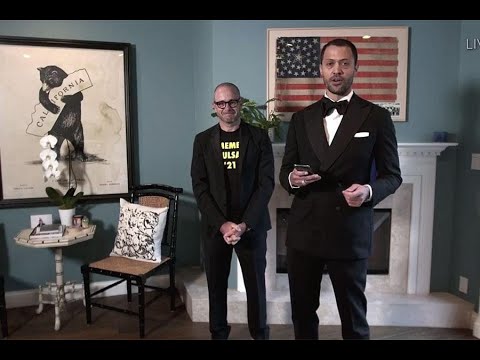

Jefferson won the Emmy for writing for a limited series, alongside “Watchmen” creator Damon Lindelof. The duo wrote the HBO show’s sixth episode, “This Extraordinary Being,” which tells the origin story of superhero Hooded Justice, dating to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

“I think I would be remiss if we didn’t recognize all the men and women who died in the Tulsa Massacre in 1921, the original sin of our show,” Jefferson said. “This country neglects and forgets its own history, at its own peril, often. And I think that we should never forget that.”

Jefferson talked with The Times on Monday about the importance of therapy, intergenerational trauma and the false pretense of nostalgia.

Congratulations on your win Sunday night. We saw the TV version of your reaction, but how were you feeling when that happened?

Thank you so much. … I was incredibly nervous. David [Lindelof] had told me before we won that he wanted me to do all the talking. He said that he wasn’t gonna say anything. So I felt like it was all on my shoulders. And I don’t consider myself a great public speaker, so I was terrified.

Did an Emmy presenter in a tuxedo hazmat suit really show up?

No, no. So, for whatever reason, some of the awards were delivered and others were not. … We did not receive one yet. I don’t know where it is, actually. It’s somewhere in the world, but it’s not with me yet.

TV writers Damon Lindelof and Cord Jefferson won an Emmy Monday night for their work on “Watchmen.” Watch their acceptance speech.

Riffing on your speech, who were you two years ago, and how did therapy change that?

Oh, man. … I’ve struggled with anger issues my whole life. And I think that for a long time, I let anger ruin my life in many ways. And I was unkind to people who loved me and who I loved, and I lashed out and I self-immolated a lot of the time. And through working with [my therapist], I feel not not angry, but just the things that I’m able to do with that anger and the ways that I’m able to channel it are just so much healthier and better.

“Watchmen” dealt a lot with anger. I really feel blessed and honored to have worked on something that allowed me to channel that anger into an artistic pursuit, as opposed to affecting my personal life. I loved it, and I think that working with Ian has really changed my perspective a lot.

Did Ian reach out last night? Did he see your speech?

He did not. We have an appointment tomorrow. My therapy appointments are Tuesdays at 9 a.m. So we’ll see. I have no idea if he saw [it], but I’m gonna let him know. Or he may see it in your newspaper.

You recently told “Fresh Air” host Terry Gross that therapy helped you understand intergenerational trauma from your dad’s service in Vietnam. Your dad was also your date to the show Sunday night. Have you talked to him about that at all?

Another thing therapy has helped me with is he and I have talked a lot about those things. I’ve talked a lot about the ways in which his anger and his trauma [have] been passed on to me. And I think that it has been actually very, very healthy for our relationship. He and I disagree about a lot, but we’re finding ways to discuss things and talk about things, which — it’s a cliche, but communication is key. And he and I are all the better for the ways that we’ve worked to discuss these things.

Which came first: The discussion in therapy about intergenerational trauma or the writing of that into the show?

The writing of the show came first. We started writing that show in September 2017. I had been to therapy before, but not as intensive as the therapy that I’ve been doing. Once we were in [the show] and writing it, I started to really see the parallels between what we were writing and my own life. And I think that helped me break through. It’s great to be able to work through some of your own issues through something you’re creating. I started realizing it, once we started writing it, that there were parallels to my [own life.]

In your speech, you also mentioned that the U.S. neglects and forgets its own history, which reminded me of Trump’s recent comments about the 1619 Project. How can we better remember our history?

I think that’s something that’s important to us, and in my episode in particular: The drug that Angela takes in the episode is called Nostalgia. I think the thing that we were trying to subtly get at is: … Really, the only people who can be very nostalgic for the past in America are straight white men. Because for everybody else, the past was painful in so many ways. The idea of being nostalgic for the ’40s and ’50s in this country is not a privilege that’s given to women or Black people or Asians or Latino people or queer people.

I think that the idea of “Make America Great Again” is just all about nostalgia. It’s all about the idea of “the past was great.” But the past wasn’t great for a lot of people in this country, and a lot of people in this world. And so I think that the thing that we were trying to get across is the idea of … this “incredible place” in history that we’d like to get back to, it’s just not the case for millions and millions of people.

Really the only people who can be very nostalgic for the past in America are straight, white men.

— Cord Jefferson

From a fictional perspective, watching the show, I stepped back and thought: Nostalgia is intended for happy memories, and clearly this is not that.

Every time I hear “Make America Great,” I think, “When was America great? Was it when there was slavery? Was it when we were putting Japanese people in internment camps? Was it when women couldn’t vote? Was it when gay people didn’t get married?” Every time I think about being nostalgic for the past, I can’t help but think [that]. Was it when we put Native Americans on reservations and the genocide campaign against them? The idea of looking longingly to the past is just something that I can’t do as a Black person in America.

What would you say to someone who’s thinking about therapy? For a long time, especially for Black men, it’s been something you couldn’t discuss freely.

I would just say absolutely go for it. There’s nothing to lose. I think that the problem is that therapy is expensive, and so I really do wish it [were] free. I think that therapy should be free. I think that all healthcare should be free, and I think that people should think of therapy as healthcare. If you can afford it, there’s absolutely nothing to lose. It has been truly transformational in my life. I think, particularly, Black people in America have been burdened by this idea that stoicism is the key. That you need to be strong and you need to face the world with a stiff upper lip, and that’s going to get everybody to … treat you with respect that you deserve.

Something that I’ve talked about with my dad recently is that he came back from Vietnam, and he didn’t go to therapy, he didn’t work with anybody about the mental anguish that he was going through. He just felt like he needed to approach the world with a stiff upper lip and stoicism. I think that that really hurt him for a long time. And so I would say that understanding yourself and really looking inward is a gift. I think that people don’t do it a lot of the time because it’s hard. It’s hard work. But when you do that, the reward is transformational.

Find out the winners of the 2020 Emmys with our complete list, updating live during Sunday night’s ceremony.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.