800 video feeds. 64 set designs. How the DNC pulled off a ratings win in a pandemic

Glenn Weiss has been a part of many unprecedented moments of live TV. He was directing the Oscars when “La La Land” was mistakenly named best picture over the real winner, “Moonlight.” The next year, he proposed to his girlfriend on stage at the Emmys.

But never in the course of his accomplished career has the 14-time Emmy winner had the opportunity to steer the course of American democracy while barefoot in his living room.

That is, until the Democratic National Convention this month.

Weiss was one of the key players who helped pull off the party’s four-night virtual gathering amid a pandemic, a mix of live and pre-recorded material that made the case for the Biden-Harris ticket, injected new life into a hidebound political tradition and — in contrast to the Republican National Convention last week — did so while adhering to public health guidelines.

“A really big part of our planning was not just how do you execute the thing and get the message out right, but how do we do this safely for everybody involved?” said Weiss, who has been part of every Democratic convention since 2000.

The virtual Democratic National Convention was designed for the COVID-19 pandemic. It ended up reinventing a fusty tradition — hopefully forever.

In a Facebook post that went viral, Weiss’ fiancee shared a picture of him directing the show via a wall of monitors in their Westside home.

Weiss’ makeshift control room was just one part of a most unusual broadcast. As it became clear that the coronavirus crisis would preclude holding a traditional, in-person convention this year, Democratic Party operatives and a team of seasoned TV professionals moved swiftly to reimagine the quadrennial gathering to nominate their party’s standard-bearer and, perhaps more critically, present him to millions of voters on TV.

The effort shattered norms about how such events are configured and will likely change how future conventions are held when people are allowed to attend large social gatherings in the future. And at least in showbiz terms, it appears to have been a success, drawing more viewers than this week’s Republican National Convention, according to Nielsen — a fact which the ratings-fixated president denounced Saturday on Twitter as fake news.

‘Our home base was the country’

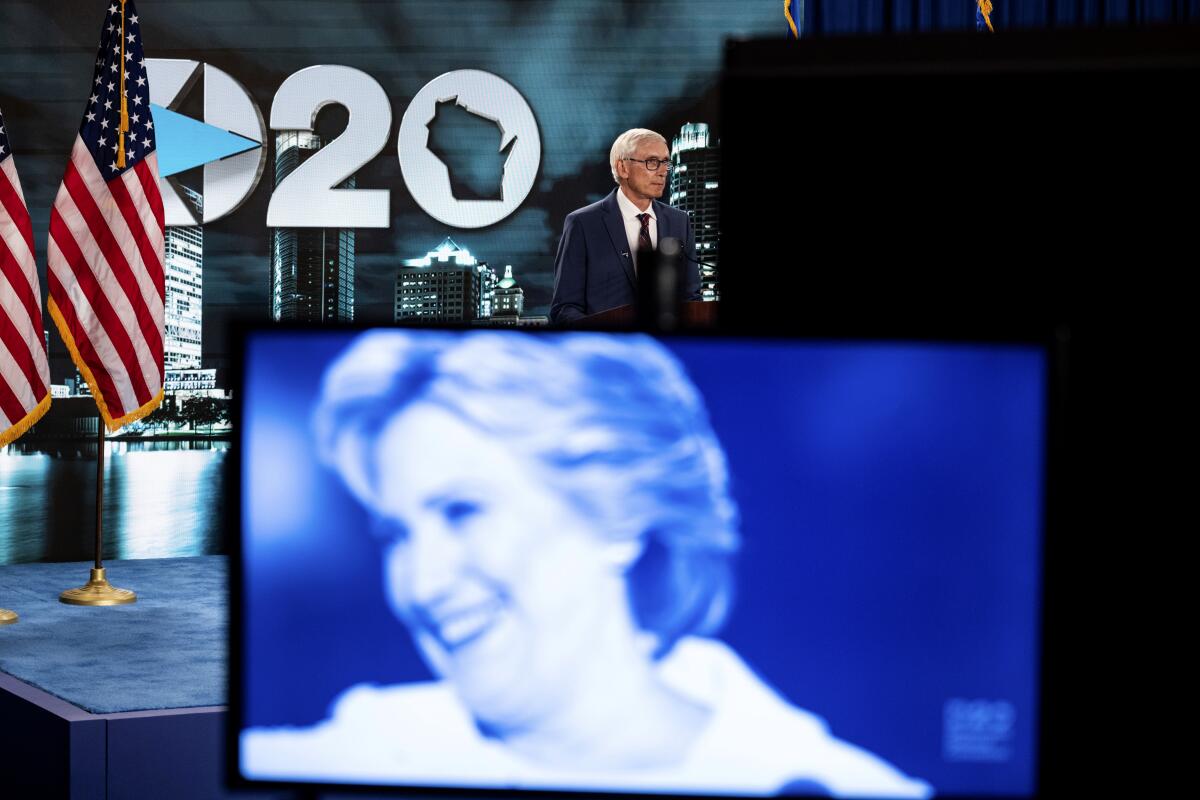

This spring, as the coronavirus surged in the nation and major events such as the Olympics were postponed, planners postponed the convention from July to August and moved from Milwaukee’s Fiserv Arena to the smaller Wisconsin Center. But they also recognized there was a growing chance that the gathering would have to be held entirely virtually, and began conceiving what such an effort would look like.

“I just started researching how people were producing engaging television in the age of COVID, where you can’t film in person or have people in the same room,” said Stephanie Cutter, the convention’s program executive and President Obama’s 2012 deputy campaign manager. “I’m not a TV producer. I know how to produce a typical convention. I had a good idea of the story I wanted to tell.”

She said they sought advice on “putting those pieces together in an engaging way to keep someone’s attention over the course of two hours when you don’t have a cheering crowd or a balloon drop, starting from ground zero.”

“We knew that we had to reach out to America as opposed to the delegates coming to us,” said executive producer Ricky Kirshner, who has produced numerous high-stakes live-TV events including the Super Bowl halftime show.

The volatile nature of the pandemic made the event a moving target. Kirshner says the convention’s art director drew up 64 different versions of the set. Weiss planned to be in Milwaukee, then Delaware, then Burbank before deciding that working from home was the best bet.

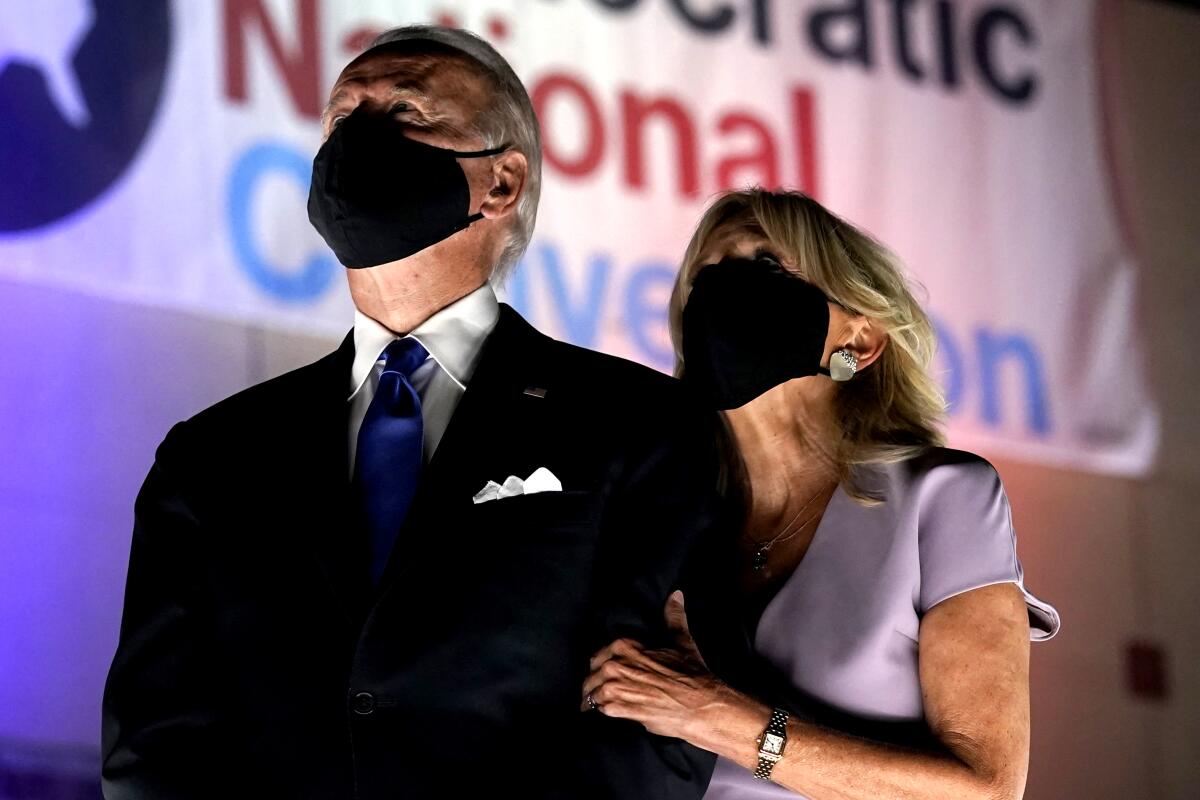

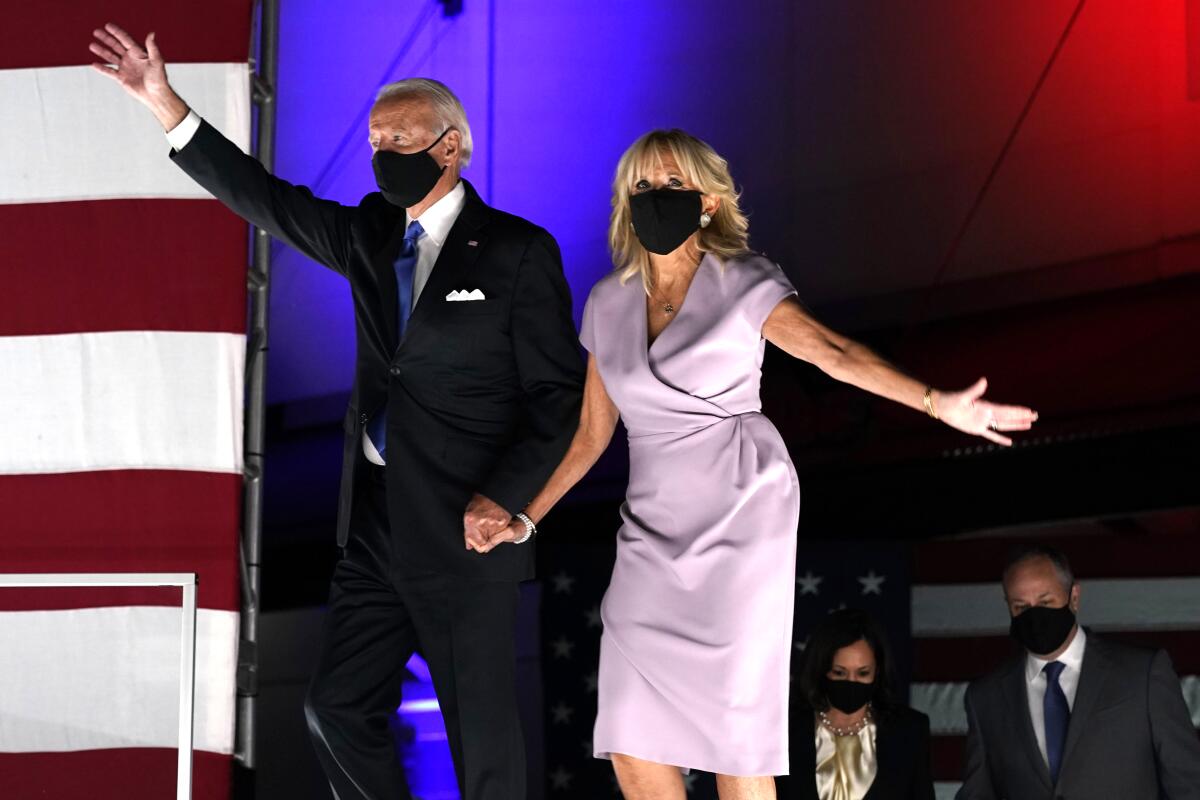

Safety was paramount. Aside from a handful of journalists and crew members who were tested daily, there was no audience at the Chase Center in Wilmington, Del., where Biden and Harris delivered their acceptance speeches. Instead of gathering in the venue, supporters parked their cars six feet apart outside to watch fireworks and cheer Biden after he formally accepted the nomination.

“We didn’t have a home base like [the Republicans],” Cutter said. “They are shooting everything at Mellon — or on federal property. We didn’t think it was safe to bring people together in that way. We produced this from wherever people were, and that’s where you got the diversity in settings. We followed the science and didn’t want to be responsible for getting anybody sick. Our home base was the country.”

In contrast, a tightly packed, largely maskless crowd of 1,500 people gathered on the South Lawn of the White House on Thursday to hear President Trump deliver his lengthy acceptance speech. As of Friday, four people who attended the in-person portion of the event in Charlotte, N.C., have tested positive for the coronavirus.

‘Your credential was your story’

As Democrats began to sketch out what the convention would look like, they decided to trim the traditional five or six hours of programming per day down to two hours. That meant some parts of normal conventions would be overhauled, if not dispensed with altogether.

They opted to keep some formalities: the gaveling in and gaveling out, the benediction, the roll call. “Beyond that, we kind of threw out all the norms and took a fresh look. How do we create engaging television and draw more people in?” Cutter said.

Producers quickly determined that an audience-free convention needed to be much faster-paced. “Not being in a room where people were cheering gave us the ability to say the attention span is only going to be two to three minutes. There is only one camera, not 10 or 12. We can’t cut away and go to a crowd shot,” said Kirshner.

This meant shorter speeches, and fewer of them. Biden’s former rivals for the nomination appeared in two multi-candidate panels, on Monday and Thursday. Normally, most would have received a speaking slot.

The change that received the most attention was the roll call — traditionally a somewhat tedious 90-minute affair in which each state and territory officially allocates its delegates from the convention floor.

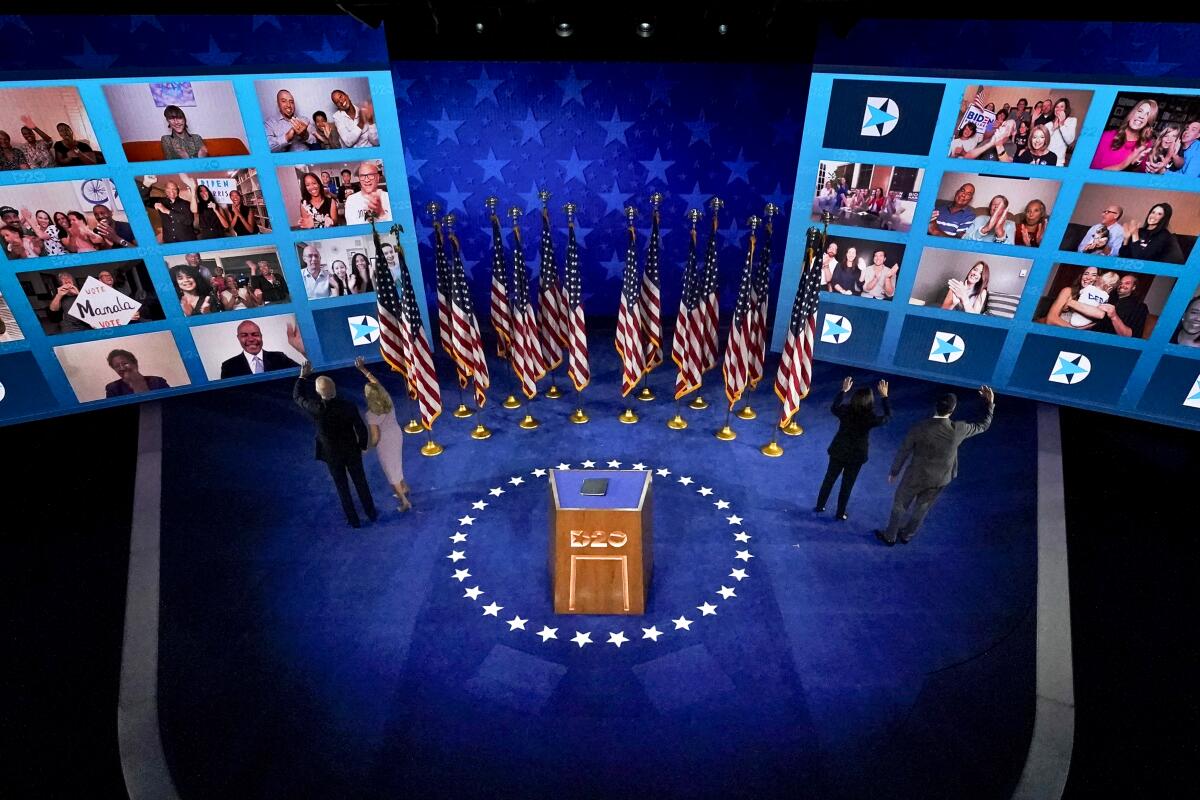

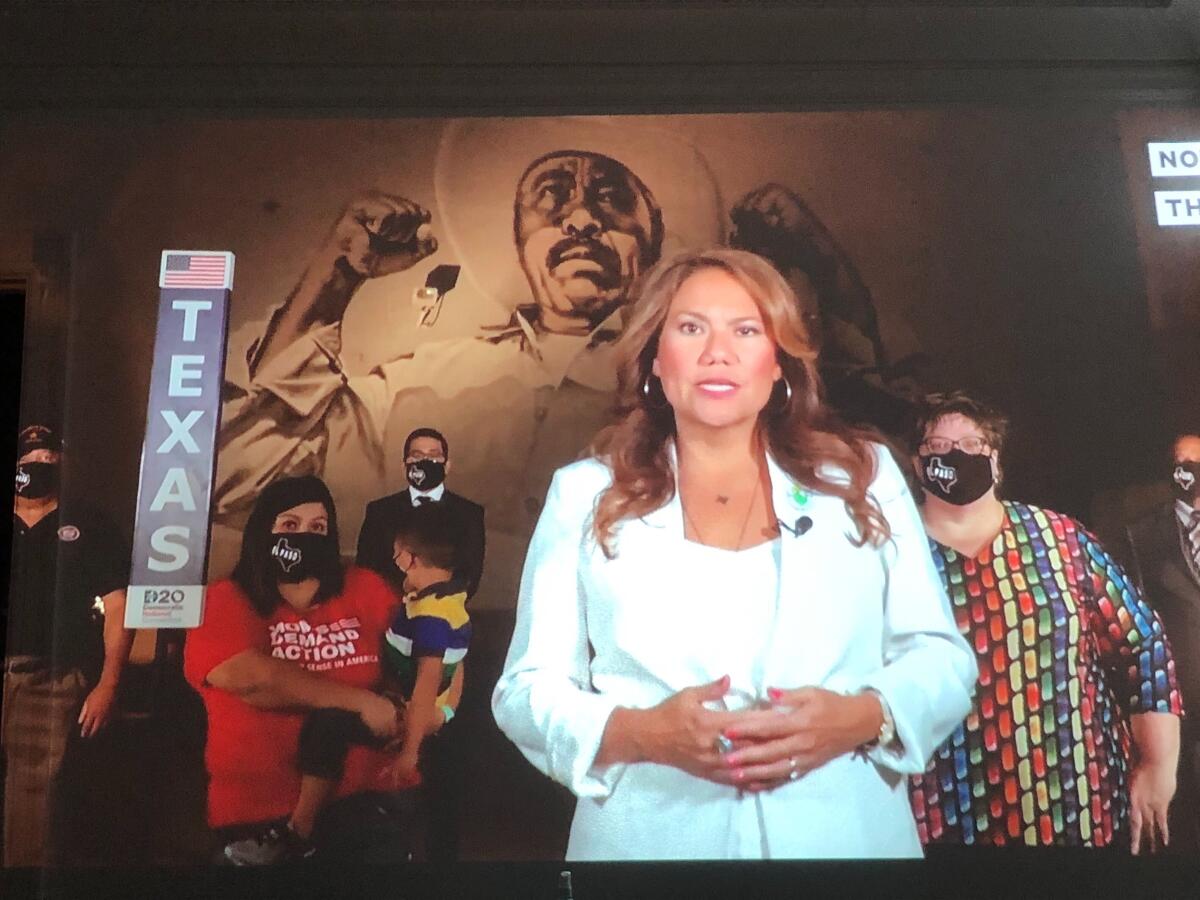

The Democrats instead deployed a montage of live and pre-taped video postcards from picturesque and historically significant locales in each of the 57 states and territories. Settings included the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., Cabrillo Beach in San Pedro and the red rocks of Colorado.

“This is a beautiful country, with scenically stunning places and places that have significant meaning for the moment and time we’re in right now,” said Rod O’Connor, senior advisor, who devised the concept. “What if we went to those places and invited people to participate in the roll call who wouldn’t normally do that, who aren’t party leaders who needed a credential to get into the building? You didn’t need a credential to participate in the roll call. Your credential was your story.”

The end result was a 30-minute travelogue that received rave reviews.

Fred Guttenberg, a gun safety activist whose 14-year-old daughter, Jaime, was killed in the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, delivered the virtual roll call for Florida from the banks of the New River in Fort Lauderdale. In remarks he wrote himself, Guttenberg recalled how Biden had called to offer sympathy after his daughter’s death.

The 70-minute Republican convention speech was down significantly from 2016.

Guttenberg was ready to go live last Tuesday when, he says, “Florida decided to be Florida. Five minutes before I was scheduled to go, it started to pour.” Luckily, he’d already taped a back-up appearance that was used in the broadcast. Guttenberg notes that all the members of the film crew he worked with were masked and maintaining social distance.

“Some of them were out in the sun all day in the Florida heat. I give everyone credit. This is not like the other convention: these are people who are taking the health of those around them seriously.”

“For the last six months, we’ve all been living in our living rooms and home offices,” Cutter said. “Being able to get a snapshot of what the country looks like right now was invaluable, showing the enormous unity across the country and wanting a better way forward.”

‘Live TV doesn’t always go as planned’

About half of the eight-hour convention was live, featuring remarks from 49 people. Only Biden and Harris spoke from a lectern in auditorium; the rest chose the settings for their remarks.

The remainder of the show was pre-taped. Some major speeches, such as former First Lady Michelle Obama’s, were shot by a professional crew. But most were shot using do-it-yourself at-home video kits containing a camera, ring light, microphone and Wi-Fi booster that convention planners mailed to participants all around the country.

Convention staffers joined voters and politicians via Google hangout to coordinate the production and troubleshoot problems as they pre-taped segments. More than 800 video feeds were uploaded and ultimately nearly 300 individual speakers’ remarks aired during the convention.

Beyond footage recorded with the kits, the convention came together with an additional 312 camera shots and about 500 crowd reaction feeds from across the country where people logged into the system with their phones.

The show had at least four production hubs.

Weiss, who normally works from an onsite truck, had a backup generator in case of a power outage at home. The celebrity hosts anchored the broadcast from the Switch, a Burbank studio. Kirshner was on the ground in Wilmington to ensure the candidates’ speeches went off hitch-free. And a skeleton crew managed technical infrastructure in Milwaukee.

Despite the extreme social distance, the production team was able to communicate as they normally do. “When we do the Tonys I’m backstage, Glenn’s in the truck,” Kirshner said. “We don’t really see each other. ... So as long as our headset worked during the show, we were OK.”

“The weird part with this is, you get done Monday night, you read a couple of nice emails,” he added. “Then you go, ‘Oh we have to do this three more times.’”

Planners were frequently up against a time crunch. Delegate tallies for the roll call, for example, could not be finalized until the Saturday before the convention started, and had to air Tuesday evening.

Developing news also impacted their plans. California Gov. Gavin Newsom scrapped plans to address the convention in a pre-taped segment because of the wildfires decimating the state. But on the final day of the event, as he was surveying fire damage, he filmed a short message on his phone that aired hours later.

Once organizers realized how much programming they were fitting into two hours every night — short, fast-moving segments on a number of issues — they knew they needed transitions so it wouldn’t feel disjointed. So they recruited Eva Longoria, Tracee Ellis Ross, Kerry Washington and Julia Louis-Dreyfus, all Hollywood actresses known for their political activism, to host one night apiece. They also put together crowd-sourced voter videos that played to Bruce Springsteen’s “My City of Ruins,” from his 2002 album “The Rising.”

“It wasn’t just a list of speakers to us, it was telling a story every night. There needed to be some connective tissue,” Cutter said.

In addition to lending some star power to the event, the celebrity moderators were also an insurance policy in case something went wrong during the live broadcast. They could step in and explain what was happening, or provide a segue into the next segment.

“Live TV doesn’t always go as planned,” said O’Connor. But aside from a few bobbles when a speaker started a beat too early or paused a moment too long before beginning, there were few obvious glitches.

All those involved predicted that while conventions would one day return to in-person gatherings with the traditional frills, this year’s experience will have an indelible impact on future conventions.

“You saw the diversity of the country reflected in the people who participated. You saw the beauty of the country and you saw a more inclusive convention and more accessible convention than we’ve ever had,” said convention CEO Joe Solmonese. “Those are things I don’t think will change.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.