‘McMillions’ isn’t your usual true crime docuseries. Here’s how they made it

Late one night in 2012, James Lee Hernandez was scrolling through a subgroup on Reddit where users share curious factoids and bizarre trivia, when a headline caught his eye: “Today I Learned Nobody Really Won the McDonald’s Monopoly Game.”

His interest piqued, Hernandez clicked on the post, which linked to a story in a Jacksonville, Fla., newspaper about a small circle of scammers who swindled McDonald’s for more than a decade. “I needed to know more and kept looking,” recalled the filmmaker, whose first job as a teenager was at a McDonald’s in the ’90s, the height of Monopoly-mania. “But couldn’t really find a lot.”

After initial reports about arrests made by the FBI in 2001, the online trail grew cold, so he filed a Freedom of Information (FOIA) request. And waited. And made follow-up calls. And waited some more.

“McMillions” on HBO, about the McDonald’s Monopoly scam uses the delayed gratification of weekly episodes to build anticipation.

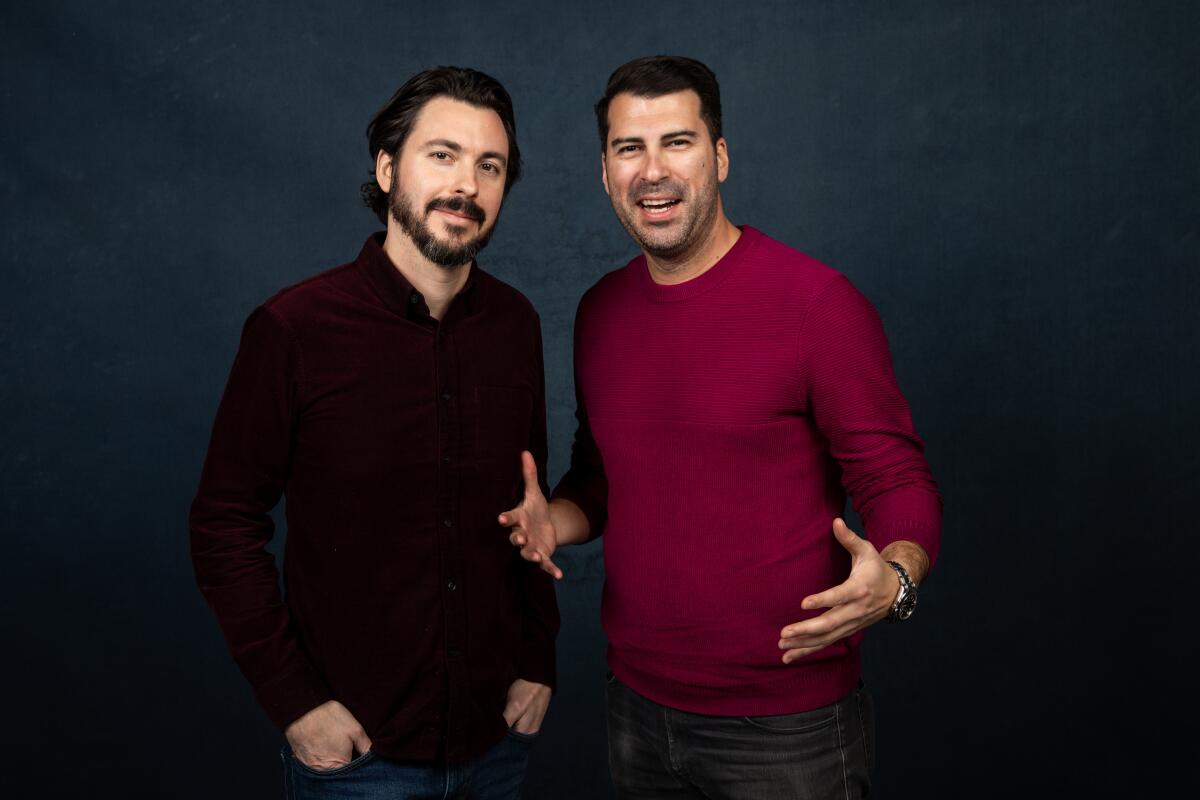

Hernandez’s journey down the rabbit hole eventually led to a six-part documentary, “McMillions,” codirected with Brian Lazarte. Using re-creations, archival footage and contemporary interviews, the series, now running on HBO, tells the story of a former cop named Jerry Jacobson who defrauded McDonald’s of $24 million by stealing the biggest winning tickets from the popular (and lucrative) promotional sweepstakes. It also details the unconventional FBI investigation — complete with a fake documentary crew — that led to his downfall.

Spurred by an anonymous tip, the FBI probe resulted in a round of arrests and a brief media frenzy in September 2001, but the 9/11 attacks pushed the news off the front page. Even though it involved one of the most ubiquitous brands in the world, the scam was all but forgotten until recently.

“McMillions” puts an often humorous twist on a flourishing TV subgenre, the serialized true crime documentary. What at first sounds like a low-tech scam — sketchy guy steals winning game pieces — unfolds as a complicated conspiracy full of absurd, tragicomic twists and colorful characters out of a Coen brothers caper. The collaborators include not only small-time mafiosos and career grifters but also a struggling single mom and a wayward Mormon — regular folks in decidedly over their heads.

“This story has a quirkiness to it. It’s not about a mass murderer or someone who is wrongfully jailed for 35 years,” said Hernandez. “It was always tough to explain our vision for this. All true crime documentaries are varying degrees of depressing, and this has very serious stakes but, like in real life, there’s an ability to be funny and tragic in the same instance. We wanted to ride that line.”

About three years after filing the FOIA request, Hernandez finally received a trove of court documents related to the case. Figuring he was onto a big story, he met with his friend Lazarte, a documentary editor (“Katy Perry: Part of Me 3D”) for lunch. (No, not at McDonald’s.)

The directors found that many people on the law enforcement side were not just willing but also eager to talk with them, including FBI agent Doug Mathews, an attention-seeking ham who defies the buttoned-up bureau stereotype.

“They said this was one of their favorite cases, but no one had ever contacted them about it before,” Hernandez recalled.

The series opens in 2001, when the FBI office in Jacksonville receives an anonymous tip about an alleged fraud being orchestrated by a mysterious figure known as “Uncle Jerry,” and the first episode is told from the agency’s perspective.

This was a strategic decision, said Hernandez: “A lot of times in a movie or TV show, the FBI is like this almost omniscient, all-knowing entity that can make two phone calls and solve a crime. We wanted to have it play out somewhat like a thriller where you’re learning the things as the FBI actually learned them.”

Hernandez and Lazarte received boxes of additional material from the FBI and the Department of Justice that hadn’t been opened since 2004 — “It was seriously like finding the golden ticket,” says Hernandez. In one of the case’s wilder twists, the FBI conducted an undercover operation, posing as a film crew making a documentary, to glean information from the supposed winners. (Mathews eagerly played the role of director.)

Hernandez and Lazarte say they ultimately uncovered far more material than they could possibly fit into six hours, so they’ve also created a tie-in podcast.

There appears to be plenty of interest in the subject. Ben Affleck is attached to direct a feature film about the fraud, based on a Daily Beast article that sparked a Hollywood bidding war when it was published in 2018 — when Lazarte and Hernandez were already years-deep into making “McMillions.”

They confess to having a momentary meltdown when they first learned about the rival project, but ultimately feel that it “validated how hungry people were for the story,” said Lazarte.

It also helped that they were able to secure the participation of many of the key players involved in the scam, though most of the people Lazarte and Hernandez asked initially said no.

“For most of them, this was, if not the worst, one of the worst things that ever happened to them and caused them to be federal criminals. So at first there was this knee-jerk reaction of, ‘I just want to avoid this and it’ll go away,’” Hernandez said.

One of the most colorful co-conspirators is chain-smoking mob wife Robin Colombo, whose husband, Gennaro — a.k.a. Jerry — was a member of the Colombo crime family and served as one of Jerry Jacobson’s main accomplices.

“When we first met Robin, she walked out of her back room wearing all red and we’re sitting in her all-red living room. We’re like, ‘Yes. This is going to be amazing,’” Hernandez recalled.

Jerry Colombo helped recruit friends and family members, who’d cash in winning tickets and then give him a cut of the money. Many of the winners had been Italian Americans, so at Robin’s suggestion, Jerry enlisted her friend Gloria Brown, who is black, to become a winner.

Monday night’s third episode introduces viewers to Brown, whose harrowing story illustrates how vulnerable people were roped into the scam.

“So often, people assume that this was a victimless crime,” said Lazarte. “Stealing from McDonald’s? So what? They have billions of dollars. They’re not hurting anybody. But that was one of the things that we really wanted to make sure you realize — that there were a lot of victims. It is so easy to convince yourself that something is OK if you’re searching for a miracle.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.