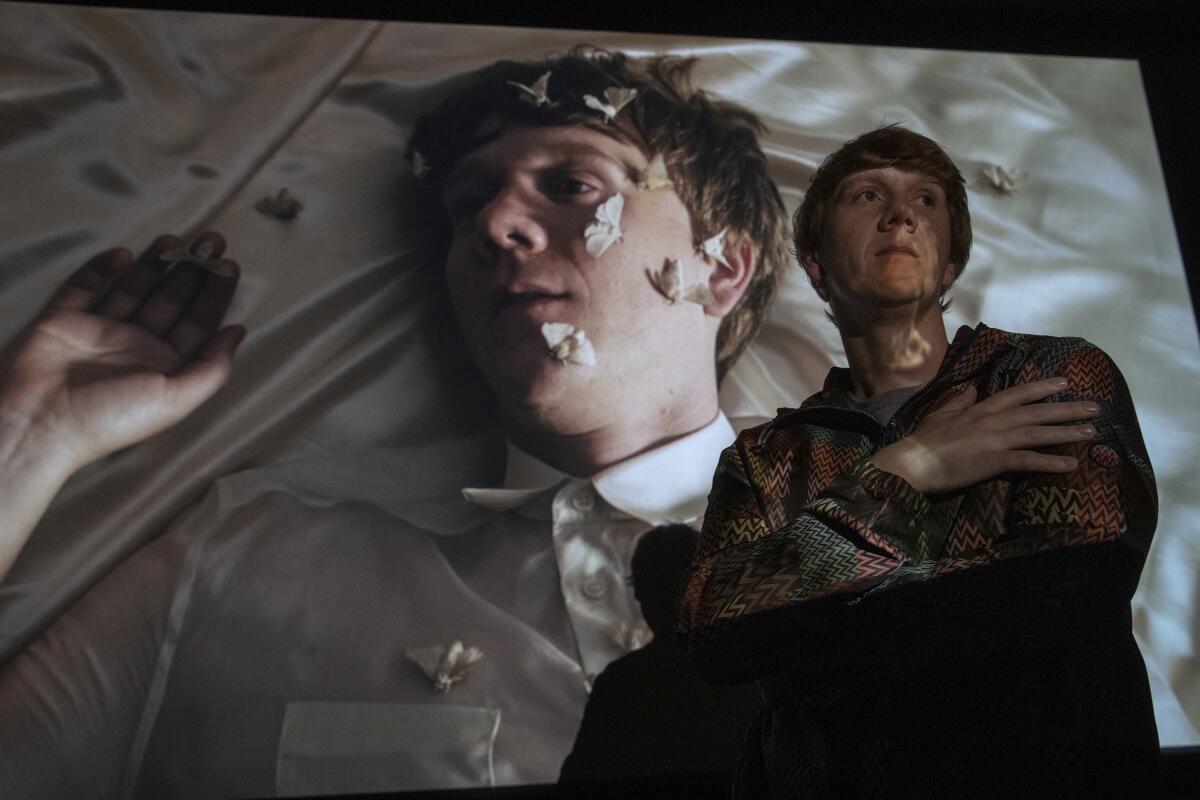

TV phenom Josh Thomas deserves your attention. This time, he’s ready for it

Josh Thomas has to see about a dog.

No, not John, his constant companion and former “Please Like Me” costar, the part-spaniel, part-poodle whose snoring during the sound mix for Thomas’ new Freeform series, “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay,” repeatedly sends the room into fits of laughter. It’s another canine in his charge that has Thomas in distress — to the point that, as we await dinner later in the evening, I offer to cut short our interview so he can check on the pup in person.

“My friend’s mum died and now I have her dog for a bit,” he whispers while fielding a call about the separation anxiety-fueled baying he’s hearing on the phone. Thomas hems and haws a moment — “What am I going to do with this dog?” — and then decides on a course of action: “He’ll be OK. He’s just going to have to tough it out for a while.” But when I remark that it was kind of him to take the dog in, Thomas deflects the compliment like an old pro.

“It is, really,” he deadpans. “It’s one of the most noble things I’ve ever done.”

Times TV writers choose their most eagerly anticipated TV shows — new and returning — of 2020.

This is Thomas’ modus operandi. At 32, the stand-up comedian and creator/writer/star of the acclaimed dramedy “Please Like Me” has been a stalwart pop cultural presence in his homeland since winning the RAW open-mike competition in Melbourne at 17, appearing as a panelist and contestant on talk, game and reality shows from the heady “Q&A” to the more prosaic “Celebrity Masterchef.” He’s honed a clear, distinctive voice in a business that rewards sameness. (“He knows what he wants” is his colleagues’ most common description of him.) And he landed the highly anticipated “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay,” his first American TV series, at Disney’s cable outlet for young, progressive audiences.

Even so, the most frequent target of Thomas’ wicked sense of humor — part shield, part shiv — is Thomas himself.

“I’m so numb to my own face, you know?” he says of his lack of self-consciousness, describing the experience of mixing sound on a series in which he’s the central character. “I sit in that room for 10 to 12 hours a day. Literally, I’ll sit there and they’ll play me saying the same sentence eight times in a row and I’ll pick the one that’s the most charming. It’s deranged.”

Though it feels, at times, like a protective shell, the patter of a semi-autobiographical humorist who hides his vulnerabilities in plain sight, Thomas carries off his rat-a-tat of embarrassing anecdotes and mordant quips with disarming gusto.

When another call comes in, this one from his mother, he puts her on speakerphone, then annotates her comments with his own. (“Great. That’ll be the pull-out quote,” he says dryly after she calls him a “mummy’s boy.”) In other stretches of this late-August evening in Glendale, where he’ll finish Season 1 of “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay” before embarking on a stand-up tour in Australia, Thomas gleefully riffs on the “sex noises” he’s recorded for the series and points out a pimple on his screen-projected face.

But self-deprecation, Thomas’ keenest instinct, is one he appears ready to temper, if not abandon entirely — and with “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay” he may have his chance.

The half-hour series, which premieres Thursday, stars Thomas as Nicholas, a young man who assumes care of his teenage half-sisters when their father dies of cancer. The extraordinarily poised Maeve Press is pint-sized, sharp-tongued Genevieve; Matilda, eager for independence after being treated with kid gloves because she’s on the autism spectrum, is played by Kayla Cromer, who is on the spectrum herself.

Idiosyncratic and colorful, treating adult and adolescent love, sex, pain and grief with remarkably funny candor, “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay” is very much in the vein of Thomas’ previous work, except here his character is older and (mostly) wiser, with responsibilities at which the earlier series’ hero would have blanched.

Perhaps it’s a function of age: “In your early 20s, you’re hopeful things are going to change,” Thomas says. “And then in your 30s you’re like, ‘This is it ... This is how I’m going to be for the next 50 years.’”

More likely, it’s one of experience. Thomas was an exceptional talent “from the absolute get-go,” according to his Australian manager and executive producer, Kevin Whyte, noting that most stand-ups don’t come into their own until their 20s. In one routine, he made “wonderfully matter-of-fact” observations about his parents’ divorce, lamenting that he was too old for them to buy his love; in another, titled “Surprise,” he detailed coming out as gay.

“He didn’t leave anything on the floor,” Whyte remembers.

This aptitude for hiding “pithy, precise” insights about human behavior inside “a sweet and innocent bonbon wrapper” attracted the interest of the Australian Broadcasting Corp., according to the network’s head of comedy, Rick Kalowski, who served as an executive producer on the series that came out of the partnership: the puckish, heartfelt “Please Like Me,” which made its creator a critics’ darling at just 26.

For Thomas, who says the series was “dead” after its first season, it was also a trial by fire.

“Please Like Me,” which starred Thomas as an aimless 20-something who comes out as gay in the pilot episode and cares for his mother after she tries to take her own life, was originally slated to air on the ABC’s main network, ABC1, but was shifted to its digital outlet, ABC2, six months before its premiere in February 2013. The move provoked criticism from Thomas and the Australian press, who questioned whether the ABC had deemed the series “too gay.”

At the time, the ABC denied that this was the case. But Kalowski, who was not involved in the decision, suggests that the criticism was not entirely off base. “I personally think there’s probably something to that,” he says. “I don’t think it had everything to do with that. But it probably didn’t have nothing to do with that.”

“They told me they moved it because it was so good that they wanted it to be the launch thing of their [secondary] channel. Which is a lie,” Thomas says, still chagrined by the ABC’s handling of the series. “And it did really well. Really well-reviewed. And it did big numbers for them by the standards of this ... channel, which is, like, 16 people versus 12. And we were like, ‘Let’s do a Season 2’ and they were like, ‘Well, no, because this channel can’t afford it.’

“You’ve got to get 150 people in a weird warehouse with no natural light to come all together to create this little moment where someone does a convincing kiss.”

— Josh Thomas, creator of “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay”

What saved “Please Like Me,” and perhaps Thomas’ television career, was a serendipitous confluence of events. First, Participant Media acquired the series for U.S. distribution on its since-shuttered network for millennials, Pivot, and joined on as a producer — earning the series a reprieve, Thomas says, because the ABC used the money earned in the deal to pay for its share of Season 2. (For his part, Kalowski believes that the show would still have gone forward without foreign investment, but not on the same terms: After the Pivot pact was struck, “Please Like Me” was promoted to ABC1 and granted an expanded episode count. Kalowski credits the series with putting the ABC’s comedy slate “on the map,” estimating that nearly 20 seasons of TV on the network have been co-produced with foreign investment since.)

Then the reviews started pouring in. Though “Please Like Me” had previously found favor with critics in Australia, it was virtually unheard of in the U.S. until it was championed by critics like The Times’ own Robert Lloyd, who called it “mostly lovely, a little wistful and doubtfully life-affirming.” In particular, the New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum, singling out the “sweetly melancholic” series and Thomas’ “diffident charisma” in a September 2013 column on the launch of Pivot, assuaged Thomas’ admittedly “bitter” feelings toward the ABC.

“Being written about in the New Yorker was the most-wanted compliment you could ever imagine a person wanting,” Thomas says. “The show had been so mistreated, to the point where I went on a celebrity diving show.” (Thomas was in dire enough financial straits at the time to appear on the reality show “Celebrity Splash!,” in which Australian stars competed against each other for prize money. He was eliminated in the first round: “I’m probably the highest-paid professional diver there is, on a per-dive basis,” he jokes.)

If the process of bringing “Please Like Me” to the public taught Thomas the television industry’s sometimes-unpleasant ins and outs, its four seasons, the last of which aired in the States on Hulu, taught him the trade.

“I’d never been on a film set,” he says. “We did pre-production on ‘Please Like Me’ and I’d talk to the first [assistant director] and I didn’t know what her job was. When I wanted to ask for something, I didn’t really know who to ask. I would sit in meetings and insist we had certain things, and I didn’t really know what I was talking about.”

Now he’s an old hand, one Stephanie Swedlove, a former Pivot executive and an executive producer on “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay,” praises for his “clarity of vision,” particularly his series’ collision of the naturalistic and the absurd.

“Working with Josh is like a dream,” she says during a break in the action at the “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay” sound mix in Glendale. “The way that he’s able to present real life through a comedic lens, I think it’s very unique.”

This sense of Thomas as an atypical creative force also won over Freeform President Tom Ascheim, who recalls meeting “this quirky man” at the network’s annual summit after “our development team kept talking about ‘Josh, Josh, Josh, Josh.’” Ascheim isn’t fazed by Thomas’ interest in potentially controversial subject matter, including mental illness, suicide, abortion and, in the new series, an adolescent girl with autism who has sex and gets drunk. He welcomes it as an antidote to the “anodyne” and the “bland.”

“I think we should be really nervous, as network executives,” he says, “if our talent has nothing to say.”

For all his love of cracking wise, Thomas does indeed know what he wants, and he musters a veteran’s authority to achieve it. When Nathan Muller, Freeform’s director of development, offers a note on a music cue during the sound mix, Thomas convincingly explains his logic, and Muller relents; later, over dinner, Thomas tells me that one of the series’ three autism consultants raised concerns about Matilda’s depiction that he swiftly quashed.

“We had one consultant who really didn’t like sex — who felt like Matilda shouldn’t be dealing with sex,” he says, an edge in his voice, adding that the other consultants were “thrilled” with the plot line. “Which is not her job, actually. Her job is to tell us if it’s authentic autism. We don’t really need her moralizing about [Matilda’s] sex life, actually.”

If anything, Thomas admits, the challenge of “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay” has been maintaining that clarity of vision, that distinctive voice, while working on a much larger scale than “Please Like Me.” Whyte describes it as moving from the “cottage industry” of Australian television to “something much more monolithic”: The Freeform series’ budget is larger. Its filming is done largely in studio. Its crew is two or three times the size. Even the conference calls involve more points of view, always at the risk of Thomas’ own.

“It’s just this very big, kind of clumsy unit that you’re trying to zoom in on a delicate moment of chemistry,” Thomas says. “You’ve got to get 150 people in a weird warehouse with no natural light to come all together to create this little moment where someone does a convincing kiss. ... Trying to keep things authentic and textured and not feeling fake when everything is so fake, that’s been the hardest thing.”

When the Australian comedy “Please Like Me” made its under-the-radar American premiere on the fledgling Pivot network, it instantly became every TV critic’s pick for Best Show You’ve Never Heard Of.

Thomas hopes “Everything’s Gonna Be Okay” can replicate “Please Like Me’s” fortuitous arc from cult hit to one of TV’s best comedies, this time for a larger audience. But he’s unlikely to pull punches to achieve high ratings. (Plus, as Ascheim says, “There isn’t a number anymore. The world’s gone weird.”) Near the end of our conversation, asked about returning to the art form, stand-up, that made his name, Thomas grows reflective, explaining that he found his success embarrassing — not by dint of any anecdote he related or quip he made, but because he felt himself an impostor.

“I started when I was 17,” he says. “And at 17 you’re not really thinking things through. So when I was 27, one day I was like, ‘These people think I think they should be here. And I don’t. I don’t think they should be here.’ So I quit. Because I’d go onstage thinking like that, and it’s not a good show. Watching somebody unravel like that, it’s not that fun.”

Six years and two TV series later, he’s changed his tune. Or at least he’s beginning to. After all, old habits die hard.

“By the time this goes to print, I might’ve quit again,” he hedges. “But now, I’m like, if somebody’s willing to book you a theater, and people are willing to pay to come, you should just ... do it. Stop being such a little bitch.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.