Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and a revelation about a rare LACMA portrait

Without fanfare, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art recently changed the date assigned to its rare Diego Rivera portrait of Frida Kahlo.

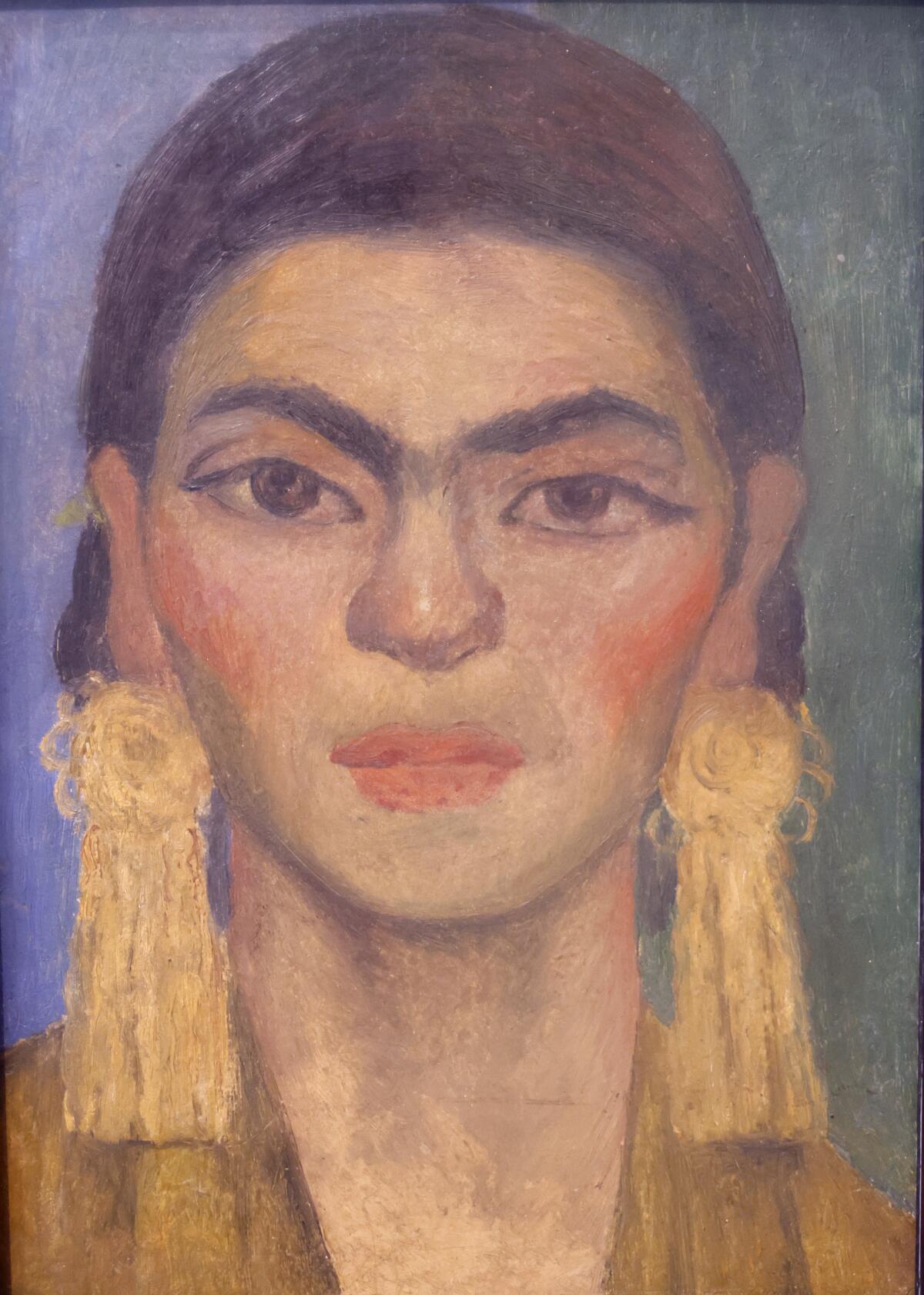

LACMA acquired the odd little picture 20 years ago, a bequest of former Southern California art dealers Bernard and Edith Lewin, who specialized in Mexican paintings. But this one was undated. For decades, educated guesswork pegged the portrait’s execution at “around 1939.”

Now, the assigned date has been securely pushed back — to 1935.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Four years is just a slight alteration, to be sure, but not an insignificant one for reasons I’ll get to. Although Rivera included Kahlo, his wife and fellow artist, in more than one revolutionary mural that he painted on big government walls in Mexico City, as well as rendering her for a few prints and drawings, the little portrait (just 14 by 9¾ inches) is the only known easel painting of Kahlo that Rivera ever did. For that reason alone, it’s important.

How did the new date come about? Serendipity struck.

Late last year I was scanning a fascinating photographic archive held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. The meticulously cataloged photo collection — a treasure trove of cultural data — includes pictures of thousands of works of art and artists, all shot between 1896 and 1975 by the firm Peter A. Juley & Son. Juley was New York City’s leading fine art photography studio, counting among its regular clients the National Academy of Design, the New York Public Library, many galleries, schools and various private collectors.

I was searching the online archive for the company’s photographs of Rivera and Kahlo. The celebrated pair, two of the greatest artists of the Modern era, were photographed by Paul P. Juley, the “son” in the company name, when they worked in Manhattan, San Francisco and, it appears, Mexico City.

In research by Mexican art dealers Carlos and Leticia Noyola and their son Diego, Juley’s name had come up as the probable author of some previously unknown photographic portraits of Rivera and Kahlo. Fifteen years ago, a controversial cache of material, some of it attributed to Kahlo, had emerged in Mexico. Among the sketches, recipes, letters and bits of clothing was a small wooden box that held several glass plate negatives. A century ago, glass plates were admired for producing sharp, detailed photographic prints. But the technology, popular beginning in the 1850s, became obsolete as the 20th century progressed.

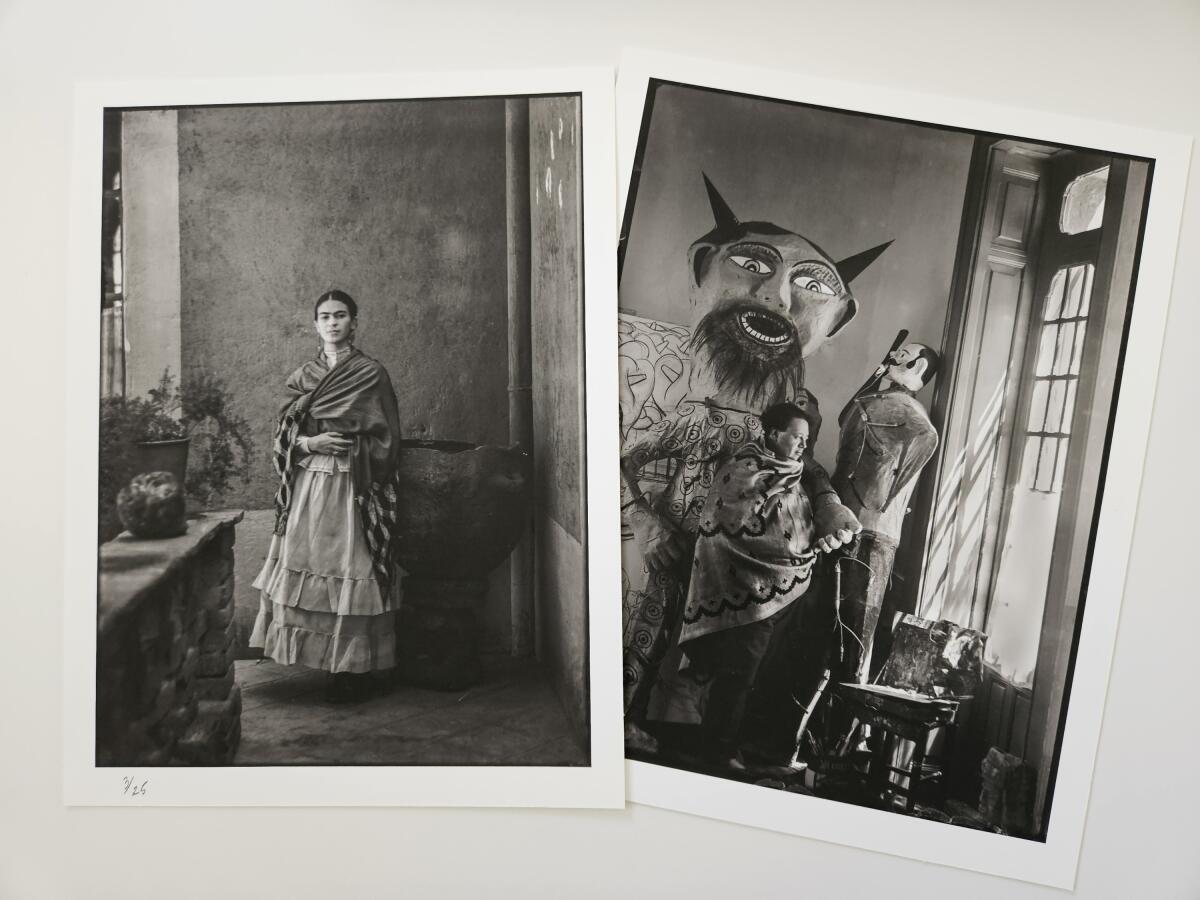

The rediscovered glass plates were digitally restored and then beautifully printed by Gabriel Figueroa Flores, the eminent photographer and son of legendary “Mexican Golden Age” cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa Mateos. (The filmmaker was the subject of LACMA’s fine 2013 show “Under the Mexican Sky.”) Rivera and Kahlo are the portrait subjects.

Among the photographs is a lovely, formal picture of a demure Frida, swathed in a handsome rebozo, a common woven shawl, and wearing a nearly floor-length tiered dress. She stands ramrod straight on what appears to be the porch of her famous Casa Azul (Blue House) in the capital’s Coyoacán neighborhood.

In another, more flamboyant picture, Diego gazes across his open paint box and out the studio window. He’s theatrically wrapped himself in the flourish of an Indian blanket. Behind him, a signature painting of a flower vendor has been partly sketched out on a big canvas, while a giant papier mâché devil looms playfully, resting a hand on the roguish artist’s shoulder.

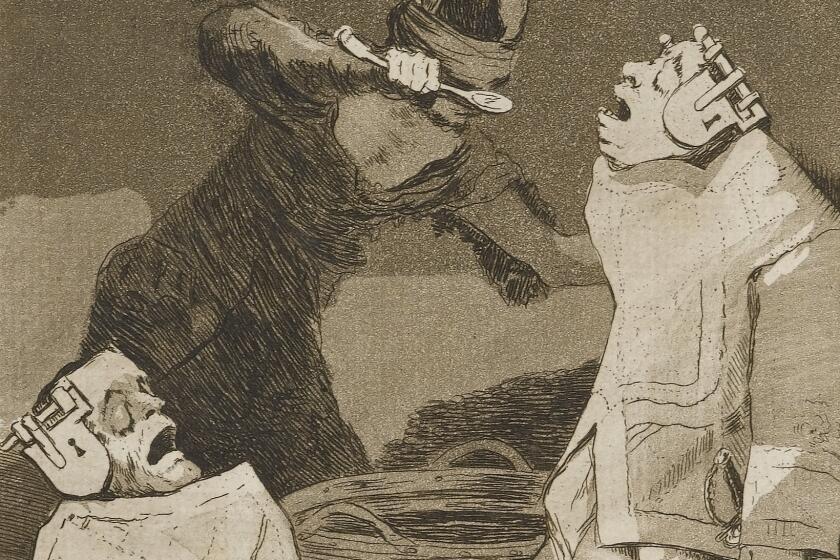

The social and political turmoil of today resonates in a mammoth, extraordinary show of Francisco de Goya’s celebrated etchings at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

The two photographs are marvelous distillations of the artists’ public personae. Both the deceptively doe-eyed young woman with a steely spirit and the macho muralist of grand ambition are hitching their artistic wagons to modern interpretations of distinctly Mexican tradition and style. The date of the photos is unknown, but judging from their faces it must be the early 1930s, with a youthful Frida in her 20s and an older Diego in his 40s.

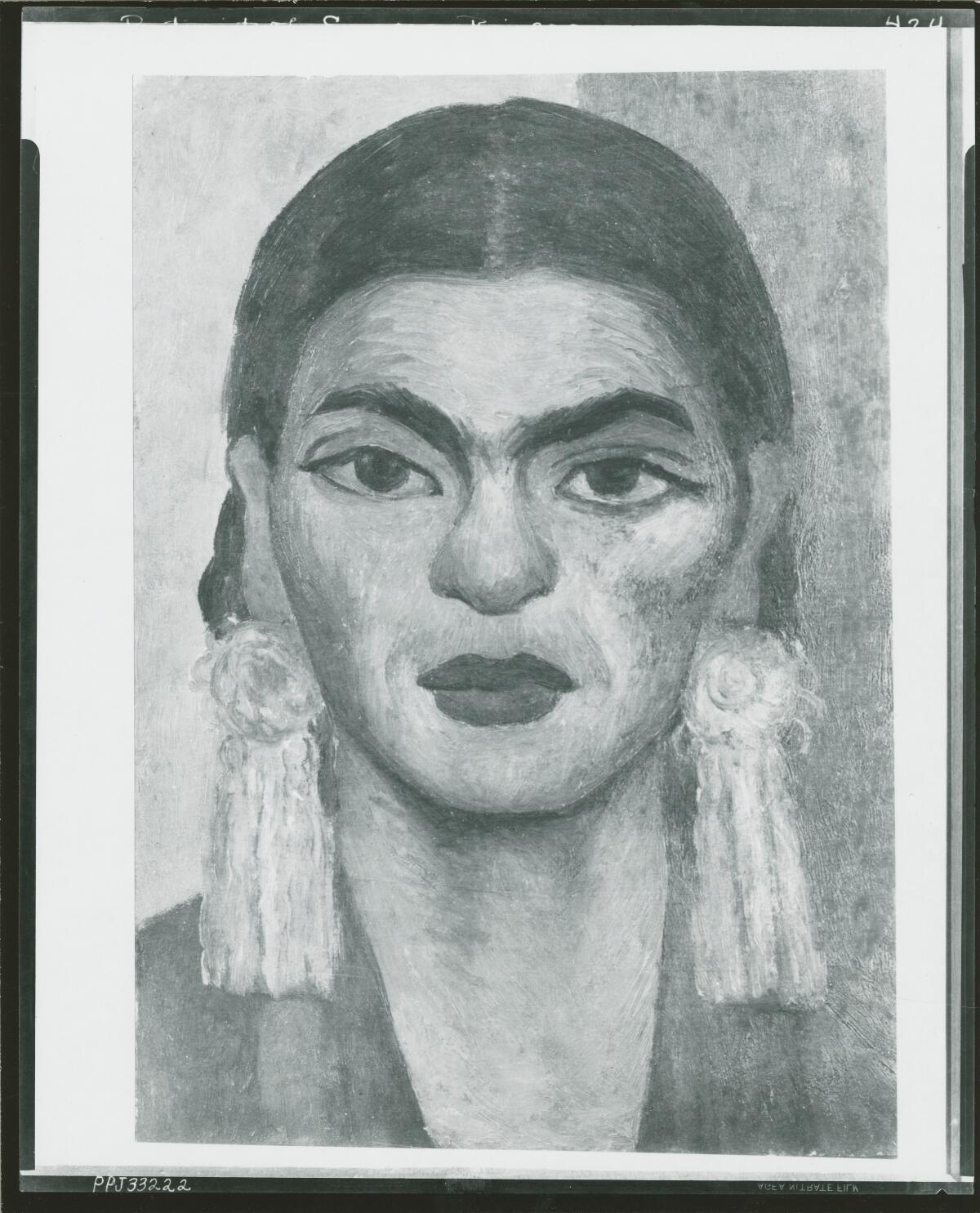

The Smithsonian’s immense Juley archive numbers 3,500 artists’ portraits and 127,000 images of paintings, drawings and sculptures. As I flipped through the digital files on my laptop, I wondered whether I might find anything visually related to these glass negative photographs, since they clearly were not among those donated to the museum. Suddenly, a surprise popped up on my screen.

LACMA’s little Kahlo portrait by Rivera stared back. The archive, assembled from carefully annotated company records, includes a black and white image of the painting. The date on the Juley photograph is unambiguous: 1935.

LACMA’s website and a gallery wall label said the painting dates to “around 1939.” But that couldn’t be correct. It’s hard to photograph a work of art that hasn’t yet been made.

I got in touch with Ilona Katzew, the museum’s top-notch curator and department head of Latin American art, to see what she thought of the material I had stumbled on. Intrigued, she looked into it.

Soon enough, a change was made. Now, the painting’s posted information reads “1935.” What this four-year time-shift means for interpreting the painting will best be determined by Rivera scholars, who know the intricate details of the complex and much-studied lives and careers of two of Mexico’s premier artists. (Some have questioned the unsigned portrait’s authenticity, without definitive results, but even the lack of a signature might be a testament to its private nature.) Still, it’s worth thinking about.

Rivera’s portrait of Kahlo is a strange little painting, made not on canvas or board but on an asbestos cement shingle. This type of shingle, now widely banned, was a standard modern replacement for traditional clay roofing materials used extensively throughout Mexico. Painting a portrait on a cement shingle seems in sync with both artists’ working-class commitment to modernizing tradition, especially when the reputation of one of the two was built on painting on architectural walls.

There’s also something rather spectral about Rivera’s painting. Loosely brushed, the portrait was surely painted from memory, not from life. Kahlo is depicted almost as a folk art icon, a righteous image intended for private veneration and small enough to be held in the hands.

A sprawling but bloodless new exhibition at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art takes on the unfolding environmental catastrophe in front of us.

Kahlo’s almond eyes are enormous, spanning nearly the entire width of her face. The famous unibrow is in place, but the equally famous mustache is barely detectable. Huge drop earrings, the same as (or at least similar to) those she wore in Imogen Cunningham’s splendid 1931 portrait photograph, shot in San Francisco, frame Kahlo’s face. Her spellbound look gets an imperial shimmer of gold in a composition that even echoes that of the sun god Tonatiuh at the center of the celebrated Aztec calendar stone, an emblem of Mexican identity then enshrined in the National Art Museum. (Today it’s in the National Museum of Anthropology.) Rivera’s flatly painted background, half blue and half green, emphasizes Kahlo’s iconic frontal stare.

The 1930s were tumultuous years in the strenuous, tempestuous, frequently adulterous relationship between Rivera and Kahlo. She was struggling as a painter and wouldn’t have her first solo show — at Manhattan’s Julien Levy Gallery — until 1938. (Her first in Mexico was not until 1953.) Rivera’s career was booming. A 1931 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, just the second monographic show the then-new museum organized (after one for Henri Matisse), was followed with exhibitions and mural commissions in Mexico City, New York, Detroit, San Francisco and elsewhere internationally.

“Around 1939” pointed toward the couple’s divorce at the end of that year, and their remarriage in December 1940 at San Francisco City Hall. For the Golden Gate International Exposition, Rivera had been commissioned to paint the vast, 74-foot “Pan American Unity” mural on Treasure Island, and Kahlo joined him there on the advice of her doctor, who was urging reconciliation.

The painting’s new date, 1935, was the year when Kahlo had had enough. She had undergone the physical and emotional trauma of yet a third miscarriage, walked out on her philandering and volcanic husband, got her own apartment in Mexico City, began an affair with American artist Isamu Noguchi and took off for New York, then Paris. Rivera’s portrait arrived at a turning point.

The new date raises questions. Before, Diego’s portrait of Frida was thought to be a hopeful expression of longed-for reunion amid all the tumult, painted as she appeared ready to perhaps reconcile. Now, the earlier date might frame the ethereal image as a memento of profound loss — a talisman for a severed relationship with a woman Rivera adored.

Differing dates suggest different intentions. That’s finally a problem for art historians to hash out, but I’d read the painting as a deeply felt keepsake, an artist’s hedge against potentially permanent loss. Rivera, even after reuniting, kept the Kahlo portrait in his studio until the day he died — through divorce, remarriage, career fluctuations, affairs and ultimately her 1954 death, three years before his own. For now, given the new date, that motive seems cogent — at least, it does unless something else turns up.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.