Alice Munro’s daughter reveals sexual abuse by stepfather, says mother stayed silent

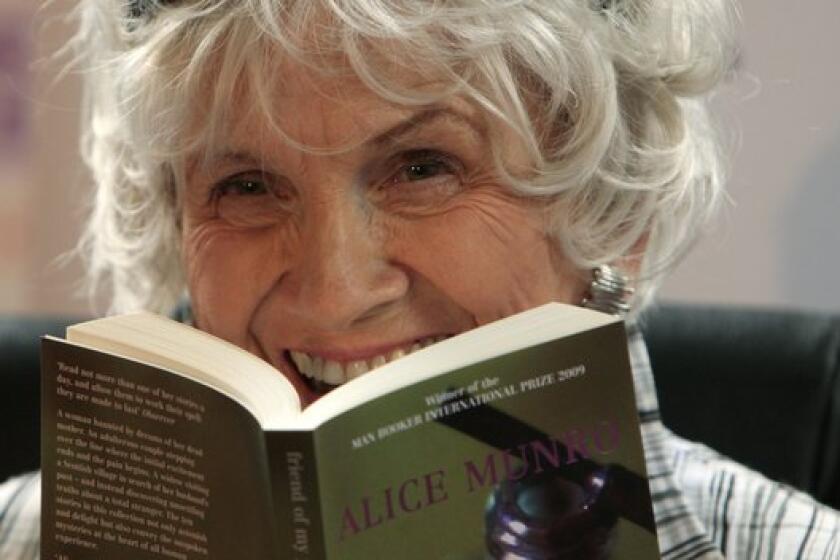

Canadian author Alice Munro established a celebrated and award-winning career with her short stories. However, more than a month after Munro’s death, her estranged daughter says that the writer failed to acknowledge one key narrative: Her second husband was a child sex abuser.

Andrea Robin Skinner, one of Munro’s three daughters with ex-husband James Munro, revealed in an opinion column for the Toronto Star published Sunday that she was sexually abused by her stepfather, Gerald Fremlin. Skinner also alleged that her mother stayed quiet and remained married to Fremlin, despite knowing about the abuse.

“She was adamant that whatever had happened was between me and my stepfather. It had nothing to do with her,” Skinner wrote.

Alice Munro, the Nobel Prize-winning short story author known for ‘Dear Life,’ has died. She was 92.

In the column, Skinner said that Fremlin assaulted her when she was 9 years old in 1976, the same year Munro married the geographer. Skinner said the abuse occurred at the author’s home in Clinton, Ontario, when her mother was out and she was left alone with Fremlin.

When Skinner returned to her mother’s Clinton home every summer as a child, Fremlin made “lewd jokes, exposed himself during car rides, told me about the little girls in the neighbourhood he liked and described my mother’s sexual needs” when they were alone, she wrote.

“At the time, I didn’t know this was abuse.”

Fremlin allegedly also had exposed himself to a friend’s 14-year-old daughter, but he denied those allegations. When she was 25, Skinner wrote a letter to her mother detailing the abuse she had experienced. Munro was not sympathetic, Skinner said. After briefly leaving Fremlin, Munro told Skinner of her husband’s “friendships” with other children and said she “had been betrayed.”

Alice Munro, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday, lives a quiet life in a small town in Ontario, Canada.

“When I tried to tell her how her husband’s abuse had hurt me, she was incredulous,” Skinner wrote.

After her revelation, Skinner said, Fremlin allegedly threatened her if she sought help from police, wrote letters to her family and blamed her for the abuse, describing her as a “homewrecker.” Despite the threats, Munro reunited with Fremlin, Skinner said.

Skinner said she finally brought her complaint to police when she was 38. Fremlin was charged in 2005 with “indecently assaulting” her in the summer of 1976. He pleaded guilty that same year and was sentenced to two years of probation, she said. He died in 2013.

Skinner, who sought therapy so she could move forward from her abuse, said she went no-contact with her mother after the birth of her twins, and never reconciled with her.

The Nobel laureate in literature imparts the invaluable lesson of how to be in the moment as a writer.

In 2013, Munro won the Nobel Prize in literature. The achievement followed decades of works, including “Lives of Girls and Women,” “What Is Remembered” and “Dear Life,” that garnered Munro praise from literary contemporaries including John Updike and Joyce Carol Oates. Skinner said she wanted her story of abuse to “become part of the stories people tell about my mother.”

“I never wanted to see another interview, biography or event that didn’t wrestle with the reality of what had happened to me, and with the fact that my mother, confronted with the truth of what had happened, chose to stay with, and protect, my abuser,” she wrote. “Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. My mother’s fame meant the silence continued.”

Skinner said she had informed several members of her family, including her siblings and her father, about the abuse. Now 57, Skinner said the “healing continues.” She wrote about her work with an organization that supports survivors of childhood sexual abuse.

Munro died May 13 at her home in Port Hope, Ontario. A cause of death was not revealed at the time. She was 92. Skinner wrote that she grieved the loss of her mother, and that “was an important part of my healing.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.