Commentary: What’s missing in two starry new productions of Ibsen and Chekhov on Broadway

Broadway found room this spring for classics from two titans of modern drama — Henrik Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People” and Anton Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya.”

It’s thrilling that at such an uncertain time in the American theater, artistic ingenuity and producing muscle were lavished on high-profile revivals of these works. The buzz-generating ensembles, pairing notable screen talents with veteran stage actors, added to the excitement.

Steve Carell is the unexpected draw of “Uncle Vanya” in a new version by playwright Heidi Schreck, directed by Lila Neugebauer at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater. Jeremy Strong and Michael Imperioli are the marquee names of “An Enemy of the People” in a new adaptation by playwright Amy Herzog, directed by Sam Gold at Circle in the Square.

These creative teams promise fresh contemporary takes on watershed dramas that cleared away the cobwebs of the 19th century stage. Moving away from melodrama, Ibsen and Chekhov gave the green light for theater in Europe and beyond to move into the 20th century with unabashed artistic seriousness. Their work was the opposite of stodgy. The realism they were ushering in had a radicalism that is difficult for us to recapture in an age that owes so much to the legacy of these writers.

Musty retreads of Ibsen and Chekhov, besides being counter to the maverick spirit of their play, can be soporific endurance tests. I’m still recovering from the National Actors Theatre production of Ibsen’s “The Master Builder,” directed by Tony Randall at Broadway’s Belasco Theatre in 1992. Playwrights who rebuked bourgeois safety when they were alive deserve better than to be given the masterpiece mausoleum treatment.

Even the Moscow Art Theatre, from which Chekhov’s plays emerged, has recognized that heritages need to be reinvented. I expected ruthless tradition when the Moscow Art Theatre came to the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1998 with “The Three Sisters” but was pleased to discover the bracing experimental nature of Oleg Yefremov’s stylized production in one of the company’s rare American excursions.

Tradition without imagination turns theater into an academic exercise. Yet when approaching the classics, there’s a balance to be struck between freedom and fidelity. The most exciting auteurs are the keenest readers of plays. Ingmar Bergman as stage director set the standard for me in this regard. The liberties he took with Shakespeare, Ibsen, Strindberg and O’Neill were at the service of exposing the dynamic core of their dramatic works.

Thomas Ostermeier’s productions of Ibsen’s “Hedda Gabler” and “Nora” (the standard German title of “A Doll’s House”), Ivo van Hove’s “Hedda Gabler,” Dmitry Krymov’s deconstruction of “The Cherry Orchard” all confirm the precept that departures from a play are all the more potent when they illuminate something at the heart of the writing.

Probably the most satisfying Ibsen experience I’ve had was Anthony Page’s 1997 Broadway production of “A Doll’s House,” starring Janet McTeer as Nora in a revival that magnified the psychology of the play without distorting its dramatic shape. Of my recent adventures in Chekhov, I remain partial to Richard Nelson’s production at the Old Globe of “Uncle Vanya,” which allowed us to eavesdrop on the characters with audio headsets that permitted the actors to perform their roles as though they were conferring in complete domestic privacy.

“Uncle Vanya,” which was published in 1897 before its premiere two years later at the Moscow Art Theatre, is rarely away from our stages for long. Pasadena Playhouse delivered a solid production, directed by Michael Michetti, in 2022. But one of the challenges of American Chekhov is the lack of resident companies that can rise to the occasion of these profoundly collaborative dramas.

The ad hoc nature of our system is exposed in Chekhov’s masterworks, which depend to an unusual degree on ensemble coordination. The plays, which take place on remote family estates, feature characters whose more or less stoical discontent stems from having lived side by side with one another for so long.

Unfortunately, the cast members of the new “Uncle Vanya” at the Vivian Beaumont seem to share only a passing acquaintance. There are fine individual performances under Neugebauer’s direction, but the production remains a patchwork of acting styles, accents and time-stamped attitudes.

Compounding the disarray, the actors look geographically lost on a set by Mimi Lien that only amplifies the vastness of the playing area. Chekhov is sometimes mistakenly credited with presenting a slice of life. Nothing could be further from the truth. His plays have a compositional quality that moves freely from realistic interaction to soul-baring monologues.

The production attempts to balance the theatricality and realism by maintaining a lot of breathing room between pieces of furniture. But the play might as well be staged in the lobby of a grand hotel.

The cast members at times appear to be visibly struggling to find their bearings. I didn’t think it was possible for an actor as natural as Jayne Houdyshell to ever look out of place onstage, but she seemed completely at sea in the role of Maria, Vanya’s mother, an old bluestocking with a bent for armchair radicalism.

Anton Chekhov’s influence is seen in the Oscar-winning film “Drive My Car” and recent novels by Gary Shteyngart and Rachel Cusk. And stage productions, including a new “Uncle Vanya” at Pasadena Playhouse, are revealing just how collaboratively open his plays can be.

The problem isn’t Chekhov’s character but the unsettled nature of the production. Costume designer Kaye Voyce doesn’t help matters with modern outfits that exaggerate personality characteristics at the expense of subtler individuality. Houdyshell’s Maria was defined by a colorful knit wrap suggesting an activist-hippie past. Anika Noni Rose as Elena, the young wife of Alfred Molina’s Alexander who upsets the household with her seductive beauty, is forced to waltz about the stage in cumbersome getups that look like nothing anyone would wear for another day of rusticating tedium.

Mia Katigbak, in the role of Marina, the kindly old nurse, is one of the few performers to escape the Bermuda Triangle of the staging by burying herself in her character’s household routine. Alison Pill, who plays Sonia, Vanya’s generous-hearted niece who’s futilely in love with Astrov (William Jackson Harper), the dashing, ecological-minded and alcoholic doctor, has only her unhappiness to fall back on. (Harper was the lone member of the cast to receive a Tony nomination.)

“Uncle Vanya” is known for its sorrowful emotion, though the anguish failed to awaken my ready sympathy. (I was quite a bit more moved by Aaron Posner’s “Life Sucks,” a modern riff on Chekhov’s play that managed to retain the pathos of the original while upping the farcical laughs.) Pill unleashes Sonia’s shattering disappointment, but I found it hard to feel her pain because the connections between characters were so sketchy.

Anger is the more enlivening emotion here. When Carell’s Vanya finally releases his pent-up fury at Molina’s Alexander, his pontificating, self-serving brother-in-law, the revival literally leaps into high gear, as Vanya jumps on the dining table to confront the man he accuses of having “destroyed” his life.

Carell seems otherwise content to fade into the background. Vanya’s middle-aged angst and resentments are, of course, the source of the play’s combustion. But Carell steers clear of anything resembling a star turn, preferring instead to be a witness to these theatrical proceedings until the crucial showdown with Alexander, whose titanic self-absorption Molina captures to perfection.

As I left Lincoln Center, I couldn’t help reflecting how this revival encapsulates so much of what is wrong with American directing. It’s not that the production is egregiously bad but that so much potential is squandered in artistic choices that seem to be made in a vacuum of tradition. (Neugebauer, it must be said, has an excellent track record with new and recent work and is being celebrated this season for her acclaimed Broadway revival of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ “Appropriate.”)

The sense of a missed opportunity is made all the more acute by the vibrancy and relaxed fluency of Schreck’s translation. I hope to experience her version in a production more mindful of what has come before and of what Chekhov’s art requires going forward.

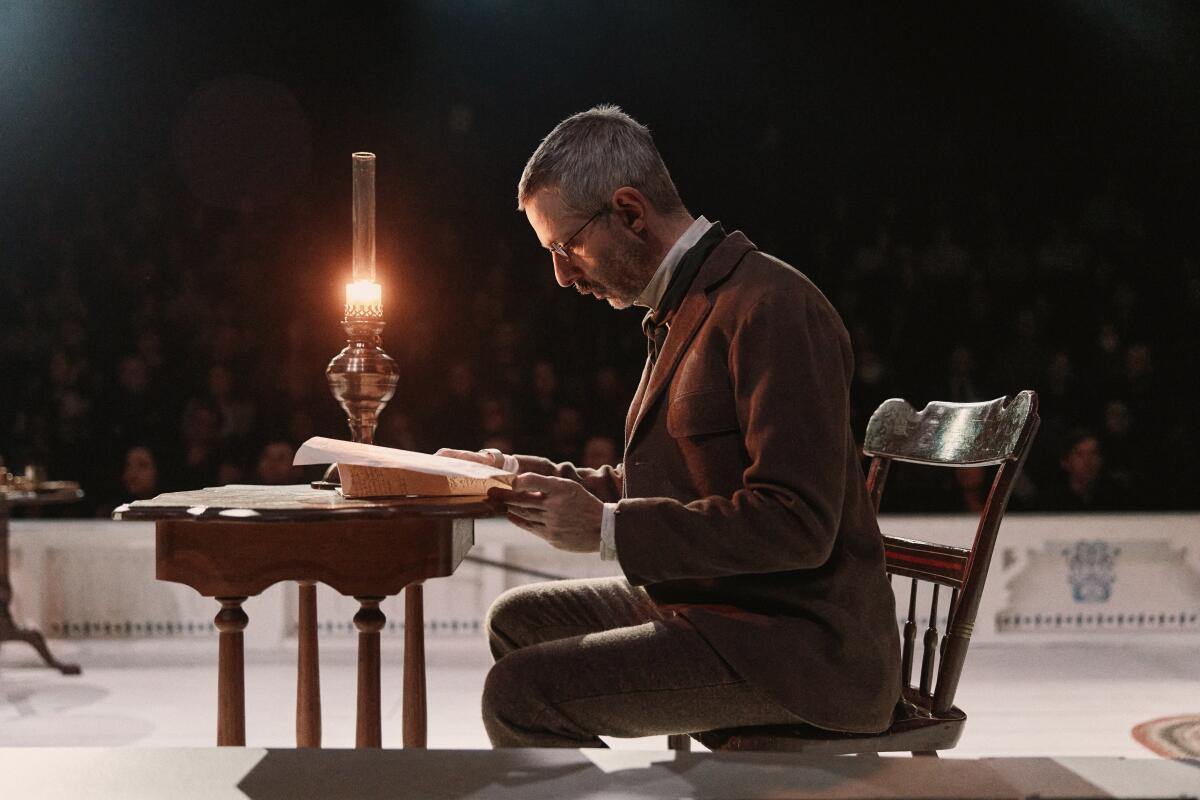

Gold has more success with “An Enemy of the People,” at least in terms of the production. Staged in the round, this modern version of “An Enemy of the People” preserves the period atmosphere of Ibsen’s 1882 drama but allows the work a modern spryness.

There’s a fluidity to the staging that incorporates all that Gold has learned along the way deconstructing on Broadway (of all places) Shakespeare (“King Lear,” “Macbeth”) and Tennessee Williams (“The Glass Menagerie”). I was gripped by the hypnotic rhythm of a production that permits the play to materialize in a free-form way, artfully assisted by the scenic design collective known as dots.

The home of Dr. Stockman (Strong), the whistleblowing doctor who becomes a pariah by exposing the medical hazard of the water system feeding the mineral baths crucial to the town’s economy, transforms into an office and then a makeshift town hall with a rowdy pub atmosphere before switching back again to Stockman’s besieged home after he has been unfairly branded “an enemy of the people.”

Herzog’s adaptation prunes away the expository overgrowth of Ibsen’s satiric drama. She and Gold (who are married) turn a debate drama into a character study of a doctor whose commitment to scientific truth puts him in the crosshairs of political power brokers.

Imperioli plays Peter Stockman, the doctor’s brother and mayor of the town with a protective interest in the economic fate of the mineral baths. The play builds to a fraternal standoff that Strong and Imperioli invest with the electricity of their respective work in TV’s “Succession” and “The Sopranos.”

Gold threads his disparate company of stage and screen actors into a tight ensemble. An anxious hush of concentration extends from the performers to the audience, who under the guise of watching two HBO stars in a stage classic have been drawn into a riveting public policy dispute with direct application to our own society.

A new adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s ‘An Enemy of the People,” written by Amy Herzog and directed by Sam Gold, is on Broadway this season in a production starring Jeremy Strong and Michael Imperioli.

All the pieces are in place for a thrilling revival, but the adaptation makes an interpretive choice that will sorely disappoint anyone who knows Ibsen’s play. Granted, that’s a small share of today’s Broadway audience, but I can’t help feeling let down by Gold and Herzog.

Dr. Stockman has the truth on his side in his public health crusade, which resonates not only with the recent upheaval over the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic but also to the ostrich-like behavior of elected officials toward the growing climate crisis. But in Ibsen’s play, he is a flawed hero, a scientist who has his own gaping blind spots.

Herzog builds sympathy for the character by turning Dr. Stockman into a grieving widower. (The character of Mrs. Stockman is cut.) The playwright further soft-pedals the protagonist by mitigating his toxic views on eugenics that in Ibsen (no matter how problematic his own beliefs) point to some basic shortcomings in humanity. (The good doctor’s hubris is comically foreshadowed in the original.)

This version of “An Enemy of the People” turns Dr. Stockman into a martyr, a role that Strong plays with impressive conviction. But this reduction of the character neutralizes the drama’s complexity. The schematic turn in the writing has the added downside of boxing Imperioli into a one-note performance. “An Enemy of the People” invites us to step out of our enervating habit of partisanship, but Gold and Herzog, perhaps fearing that it’s too dangerous a time to muddy the ideological waters, decline the offer.

I found myself more interested in the twists and turns of Dr. Stockman’s supporters connected to the town’s newspaper who, one by one, betray him. Matthew August Jeffers’ Billing, Caleb Eberhardt’s Hovstad and Thomas Jay Ryan’s Aslaksen have more gray area to maneuver in before revealing their cowardly colors. But the performance that stands out is Victoria Pedretti’s as Petra, Dr. Stockman’s daughter, who combines her father’s unyielding integrity with her late mother’s long-suffering accommodation of her husband’s narcissism.

Strong, as we know from his portrayal of Kendall Roy on “Succession,” has a talent for self-abasement. He plays the victim vividly and is quite adept at showing the obtuseness of a know-it-all. But there are darker shades in Dr. Stockman that ought to be drawn out.

As grateful as I was to finally see a major production of “An Enemy of the People” and to revisit “Uncle Vanya,” I wish that revivals of classics on our most prominent stages were more of a regular occurrence so that our theater culture might be in a better position to appreciate what has allowed these plays to endure while doing what needs to be done to make them new again.

‘Stereophonic,’ ‘Merrily We Roll Along,’ ‘Illinoise,’ Alicia Keys’ ‘Hell’s Kitchen,’ Sarah Paulson, Jessica Lange, Rachel McAdams, Jeremy Strong: This year even known quantities had to stretch.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.