1 million Mexican Americans were deported a century ago. A new L.A. audio tour explores this ‘hidden’ history

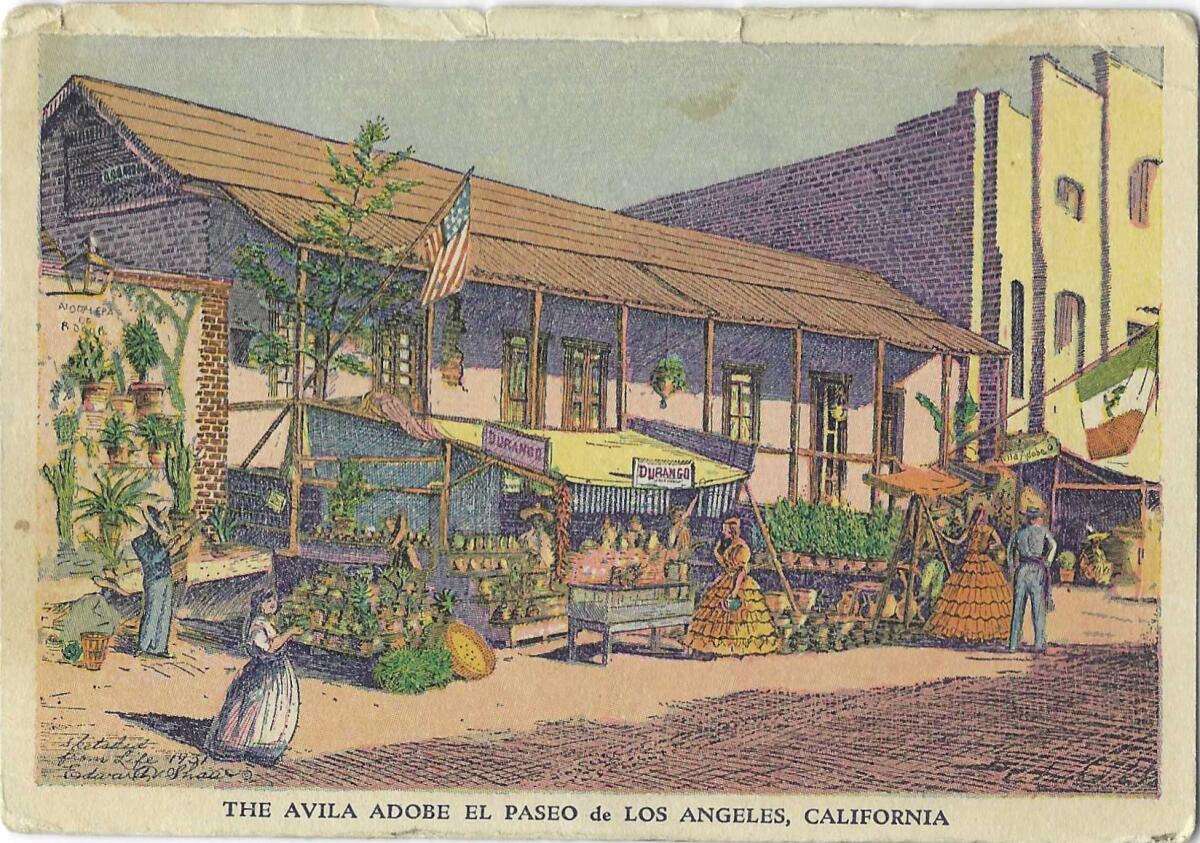

Olvera Street, adorned with brightly colored papel picado (perforated paper) and teeming with lively puestos (food stalls), did not always look as vibrant as it does today. While the historic pedestrian street and El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument attract about 2 million tourists annually, many don’t know how the area came to be or that it was the site of the first public immigration raid in Los Angeles.

A new self-guided audio tour, presented by the California Migration Museum, explores both the origin of this storied area and the “hidden” history of the La Placita raid that ultimately led to the deportation of as many as 1.8 million Mexican Americans across the country in the 1930s.

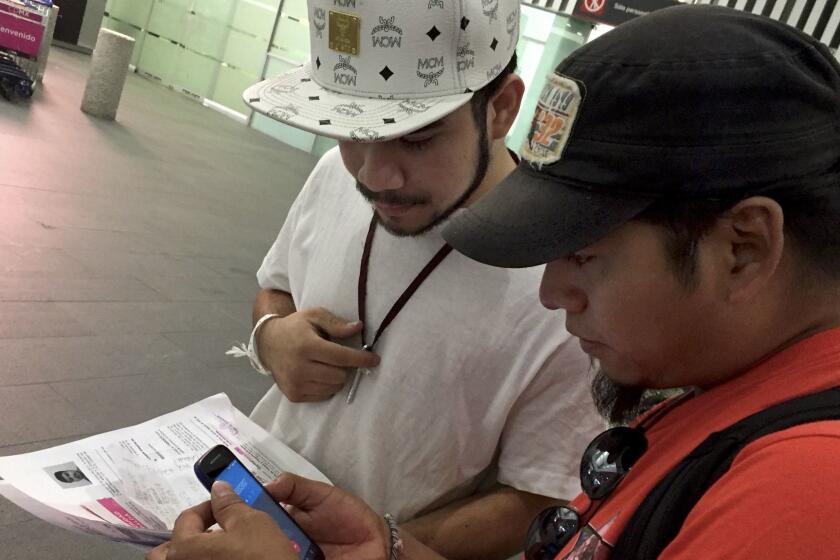

The immersive experience, titled “Ni de Aquí, Ni de Allá” — meaning neither from here, nor from there — is narrated by Karla Estrada, an activist and advocate for immigrant justice. The founder and director of the museum, Katy Long, contributes to the story’s narration as well. The tour, which is also available as an interactive, 360-degree YouTube video, is part of the museum’s “Migrant Footsteps” series, which offers similar free audio walks in the San Francisco area.

A Random INS Roundup Set the Tone for Decades of Ethnic Tension

The project took nine months to develop and was funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The museum has four walking tours based in San Francisco; this new tour is the first to trace the rich migration history of L.A..

In an interview with The Times, Long said the museum wanted its first L.A. experience to trace the history of La Placita and Olvera Street because it “made sense on so many levels.”

“It is the space where Los Angeles was founded,” Long said. “That area has this long, layered history going back to the Native Americans, who were there before the Pobladores arrived, and then you have these layers upon layers of different migration histories that all center and circle around La Placita.”

Long said the California Migration Museum has plans to create more tours in L.A. The “short list” of ideas and topics they’d like to explore in future experiences include California’s Proposition 187, the Great Migration and the history of Jewish Los Angeles.

A city commission ordered the current owners of La Golondrina Cafe on Olvera Street to pay over $242,000 in back rent and fees in the next 30 days or leave.

A century ago, the subset of downtown L.A. where La Placita and Olvera Street exist today was home to Mexican, Chinese and Italian immigrants. The plaza became known for “radical political rallies” by the 1920s. Because it was such an active gathering spot, government officials launched a highly visible immigration raid at the plaza in February 1931, Estrada says in the audio tour.

The tour’s narration details how the public became more hostile toward immigrants during the beginning of the Great Depression. In L.A., officials made plans to expel immigrants to create job openings for U.S. citizens, and the La Placita raid was one of the first steps of that effort.

The audio features reenactments of the scene of the 1931 raid, with voice actors depicting police and immigration officials demanding immigration papers from the 400 Mexicans who were enjoying music and food at the plaza that day. Estrada says prior to 1917, there were significantly fewer checks at borders and less restrictions on immigration, so many of the people there did not have documentation.

While only a “few” people were deported as a direct result of the raid, many immigrants were intimidated by the officials and feared deportation following the public scene. After the larger L.A. community criticized the intimidation tactics, Estrada says immigration officials switched their focus to “coercing” the poorest immigrants to voluntarily return to Mexico.

Long asks in the narration, “When you leave because you feel you have no other choice, is that really voluntary?”

Over the next decade following the raid, more than a million people across the country, tens of thousands of whom were children born in the U.S., making them American citizens, were deported to Mexico or left under coercion.

The final stop on the tour is a monument, unveiled in 2012, acknowledging California’s history of Mexican repatriation.

“The State of California apologizes to those individuals that were victims of this ‘repatriation’ program for the fundamental violations of their basic civil liberties and constitutional rights committed during this period of illegal deportation and coerced emigration,” the description on the monument reads.

Long said this chapter of L.A. history has “so many contemporary resonances” with ongoing conversations about immigration to the U.S.

“The story felt like a way to connect with so many questions that are still being asked today about what it means to be Mexican American in the United States today,” Long told the The Times. “What does it mean to be a second-generation immigrant? Do you belong, and how contingent is that on having the right paperwork?”

The sliding doors opened, and suddenly Roger Perez was back in Mexico.

The tour also examines the origin story of what we know as modern-day Olvera Street, including Christine Sterling‘s efforts to transform the area from a “forgotten” part of town to a treasured cultural site and tourist attraction. Estrada notes in the tour’s narration that Sterling wanted to present a more “colorful” history but that her creation was “far away from the reality of Mexico.”

“This place is an invention, a fantasy,” Estrada says of modern Olvera Street, especially compared with her Mexican hometown of Cuernavaca. “The plaza there does not have colorful stands, nor the Día de los Muertos in July. This place reminds me of the movie ‘Coco.’ Vendors with embroidered shawls and dresses, bright Catrinas and sugar skulls.”

Sterling lobbied L.A. officials and fought for the area’s preservation and development in the 1920s until Olvera Street’s grand opening in April 1930, just a year before the first immigration raid in the area. The tour includes interviews with the owners of Casa California on Olvera Street whose relatives hold Sterling in “high regard” for giving their family the opportunity to escape poverty decades ago. Her portrait is framed at the entrance of their shop.

Despite her contributions to Olvera Street, the narrator acknowledges Sterling’s complicated relationship with Mexican Americans, saying she had a “white savior complex” and calling her “patronizing and autocratic.” Much of the criticism of Sterling comes from her effort to obscure a 1932 mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros, titled “América Tropical,” that depicted a country “oppressed and destroyed by imperialism.”

By the end of the 1930s, the mural was entirely whitewashed and would not be seen by the public again until 2012, after a years-long conservation effort by the Getty.

“Ni de Aquí, Ni de Allá” incorporates the origins of Olvera Street and its status as a cultural attraction into the larger conversation of the history and current state of Mexican immigration to the U.S. Estrada notes that “eating tacos or dancing in the street can’t erase the dark reality that many Mexican immigrants live in fear of deportation.”

One of Estrada’s final remarks on the tour speaks to that effort to bridge this untold story with our present: “Unless we remember our history, we will be condemned to repeat it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![LOS ANGELES, CA - SEPTEMBER 28, 2023 - Bertha Gomez, right, and her son David Gomez, the new owners of La Golondrina Cafe, stand inside the famed restaurant that remains closed on Olvera Street in El Pueblo de Los Angeles on September 28, 2023. The Gomez' have not been able to open the business because of a damaged sewer line into the building. La Golondrina Cafe]has been closed since March 2020. They are locked in a lawsuit with the city, because they claim that the city is responsible for the repairs, while the city argues otherwise. The Board of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument Authority Commission on Thursday oversaw a hearing and decided that the Gomez' should be evicted from the location, nearly 95 years after the business first opened. The previous owners were the original family who started the business and it's considered one of the oldest Mexican restaurants in the city. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/a7675b9/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6720x4480+0+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F44%2F88%2Fe2b72d1641ec8c2de63a02da4ef8%2F1353501-me-0928-la-golondrina-cafe-gem-001.jpg)