In blow to L.A. art scene, Hammer Museum director Ann Philbin to retire in 2024

Generational change is coming to the UCLA Hammer Museum. Ann Philbin, director of the Westwood cultural mainstay since 1999, will step down from the post in fall 2024, wrapping up a quarter-century at the helm of an institution that she led from local embarrassment to national prominence.

Philbin — or just “Annie” to the art world — notified Hammer board members of her plans late Tuesday and informed assembled staff at a museum-wide meeting on Wednesday. In an interview, she said she has no specific blueprint for what comes next. She’ll take some time off with her wife, public relations and communications executive Cynthia Wornham, and sort out her affairs between now and her departure next year.

Philbin was adamant, however, that another museum director job would not be in her future.

The retirement announcement will no doubt be received with some shock — a sign of Philbin’s successful track record and close identification with the institution — although perhaps not entirely. The final phase of the two-decade, $90-million Hammer Museum expansion and renovation, designed by Michael Maltzan Architecture, opened in March, and the conclusion of such major building projects is often the moment when directors depart. Questions such as “What’s next?” naturally arise.

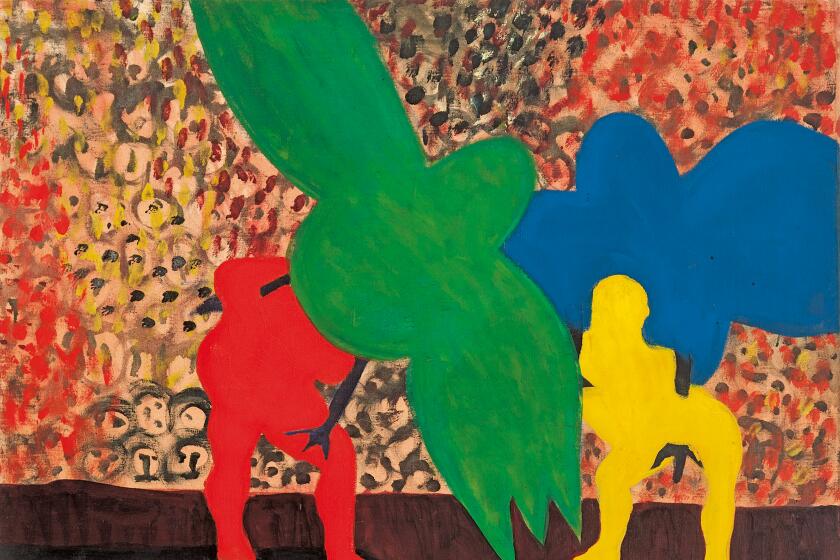

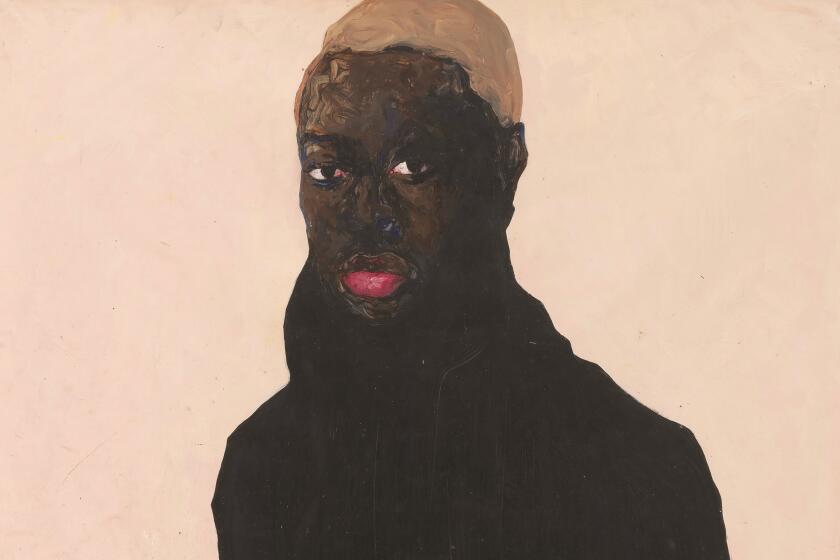

The Hammer Museum’s robust exhibition program under Ann Philbin’s directorship has been central to its rise.

The decision to retire was the product of a year’s worth of rumination, Philbin explained, and now, at 71, she is ready to move forward. Two related considerations influenced her choice to give a year’s advance notice.

One concerns larger shifts in the museum’s staffing. The Hammer board will need time to select a headhunter to begin the sure-to-be-lengthy search for a new director. And the departure of longtime chief curator Connie Butler over the summer for the directorship of PS1, the Museum of Modern Art’s contemporary outpost in Queens, N.Y., meant that a critical top position also would be vacant. It will remain open, to be filled by a new Hammer director.

Second is museum participation in the Getty Foundation’s next Pacific Standard Time extravaganza, with more than 45 citywide exhibitions, launching next September. “Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice,” the Hammer’s contribution to the science-themed program, will include six new large-scale commissions among 35 existing works that explore connections between climate change and environmental justice.

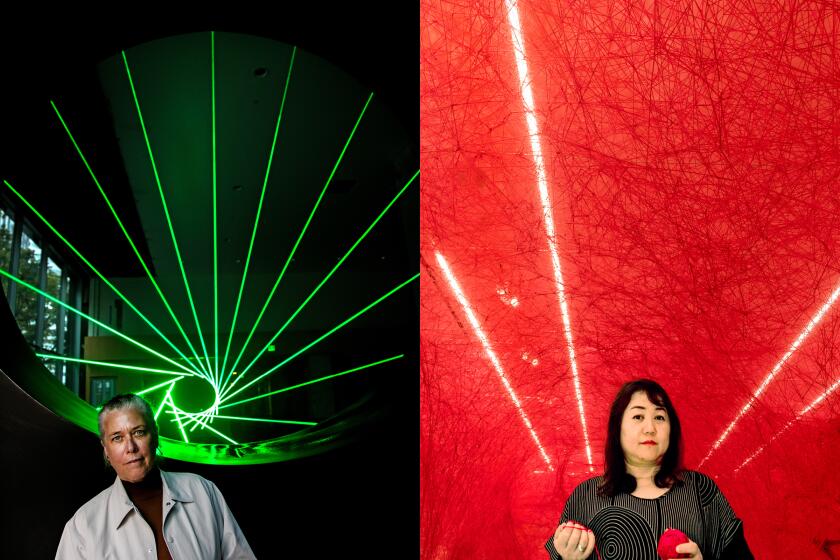

The Hammer Museum is debuting large-scale immersive installations in its lobby and new gallery by artists Chiharu Shiota and Rita McBride to mark the completion of its new building project.

Circumstances sharpened in May, when news of Butler’s planned departure broke. Simultaneously, senior curator Aram Moshayedi signed on as curator in residence for the Tamayo Museum in Mexico City and Pablo José Ramírez left London’s Tate Modern to join Erin Christovale as new full curators at the Hammer.

Change was underway and continued through the summer, with more staff shifts.

Effective Monday, Naoko Takahatake from the Getty Research Institute succeeded Cynthia Burlingham as director of the Hammer’s Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. (Burlingham remains deputy director at the museum.) MoMA painting and sculpture curator Paulina Pobocha will leave New York to follow Moshayedi in the senior post. He’s agreed to stay on for at least a year as interim chief curator, ensuring continuity until a new Hammer director permanently fills that key post.

In the 1980s, when the art world was struggling to distill the pain and loss of the AIDS epidemic, Ann Philbin, a young curator with an avant-garde eye and an activist’s edge, walked into a New York gallery and came upon a simple and searing work: A white, scoured sink by sculptor Robert Gober.

Philbin came to Los Angeles from the small but influential Drawing Center in New York. When she arrived in January 1999, I wrote in The Times that she was taking the reins of a young art museum with a troubled past and huge promise. Namesake oilman Armand Hammer had wasted $60 million on a barely functional vanity building, left unfinished nine years later, and shafted the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in the process, walking off with a handful of major paintings and sculptures he had repeatedly promised to donate to the Wilshire Boulevard museum, where he was a trustee. After the donor’s death, veteran museum director Henry T. Hopkins helped stabilize the place, which was absorbed by UCLA in 1994. But Philbin’s arrival as director began the new era in earnest.

A quarter-century on, that “huge promise” has been largely fulfilled. The Hammer holds its own in the international field, and its contemporary program is unrivaled among American university museums. About $300 million was raised, the annual operating budget grew sixfold to $30 million and admission charges were dropped in 2014. The Hammer now has 3,000 members.

The timing was fortuitous. Since the 1980s, Los Angeles had steadily established itself as a key global center for the production of significant new art, at least equal to existing hotbeds in Germany, London and New York. But the bracing phenomenon had no institutional champion. As the new millennium approached, the absence was starting to be felt. It required building a platform for L.A.-based artists and for artists imported from elsewhere.

The young Museum of Contemporary Art, one of two potential candidates for the task, had a mandate to be international. The other, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, had a founding commitment to explore art’s worldwide history. Philbin’s career had been limited to commercial and nonprofit galleries in New York. Approached about the Hammer job, and encouraged by artist Lari Pittman, a UCLA faculty member, she looked across the country, where she had been keeping tabs on the astonishing L.A. efflorescence. She saw an opening, and she took it.

Sometimes, distance helps one see an art scene more clearly. Her commitment to providing significant institutional support eventually gave birth to a signature Hammer program, “Made in L.A.,” now an eagerly anticipated biennial survey exhibition. The sixth edition opened this month to enthusiastic reviews.

Philbin was equipped with a few tools that would prove to be essential to turning the moribund Hammer into a thriving hub. Some were simple and to be expected: Right out of the box, she launched Hammer Projects, commissioning single-artist presentations in a lobby gallery, a stairwell or another modest space, along with an unassuming brochure for documentation. To date, 166 Hammer Projects have been realized.

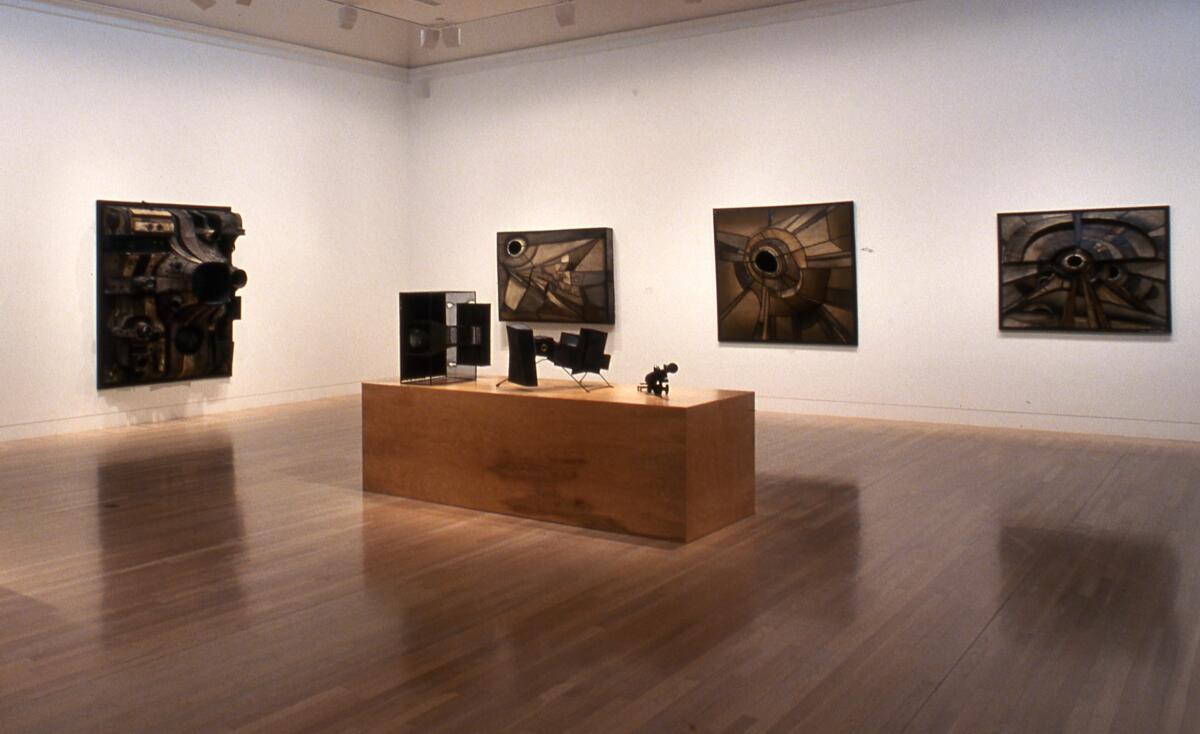

The museum also needed an unexpected showstopper — a large exhibition from left field that would startle and engage. “Lee Bontecou: A Retrospective,” which opened at the Hammer 20 years ago this month, proved to be that show — the first of many striking presentations. Co-organized with the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, its 70 sculptures and 80 drawings revived interest in a long-reclusive American artist, one of the few women to gain traction in the 1960s. Securing her reputation as an overlooked major figure, the Hammer had arrived as a museum of national significance.

The Hammer Museum’s sixth biennial survey, offering hugely diverse work made by the show’s 39 artists, is marked by the pandemic catastrophe and materiality.

Programs like these galvanized attention among the city’s burgeoning artist community. They represented the director’s belief, shaped by her experience as a painting student at the University of New Hampshire, that artists are an art museum’s most important constituency. Students, benefactors and the general public are all essential, but there is a hierarchy. If the artists aren’t with you, the museum won’t — can’t — be top-tier.

“Other institutions give Hollywood stars free passes to their events; at the Hammer, it’s artists who get the special treatment,” Los Angeles Magazine once marveled.

It almost didn’t happen at all. In 2001, Hammer Foundation president Michael A. Hammer, grandson of the late founder, quietly threatened to pull the trigger on a contract clause establishing the museum with University of California regents, giving it the right to reclaim the collection and some endowment funds, if strict donation rules were breached.

It took six years of secret negotiations, led by board chairman and former Sen. John V. Tunney and John Walsh, director emeritus of the J. Paul Getty Museum, but a deal was finally reached. The foundation got 92 mostly second-tier paintings — the notable exception being Chaïm Soutine’s “The Valet” (1929) — together valued at $55 million. The museum retained the cream, including trademark paintings by Rembrandt, Vincent van Gogh and John Singer Sargent, plus 100 more, valued at $250 million; and an extraordinary group of 7,500 works by 19th century French satirist Honoré Daumier and his contemporaries, valued at $8 million. The potentially ruinous matter was settled in 2007; Michael Hammer died in 2022.

Philbin is known as a sometimes difficult but generally fair administrator. The vital position of chief curator was a revolving door for a while, filled by talented if relatively short-term assignments. The 2013 hiring of Connie Butler brought much-needed stability.

Philbin also had a talent not often recognized as essential — the capacity to say “no” to formidable forces. And to mean it.

As the museum was establishing itself, some within UCLA’s nationally ranked art department began to push for using the galleries for annual faculty and MFA student shows. Philbin refused. The campus has the Wight Art Gallery for training in practical skills, and the Hammer had bigger fish to fry. If it succeeded, faculty and students would benefit.

It did, and they have.

Another emphatic “no” greeted one of the most powerful figures in the L.A. art world. Billionaire collector and philanthropist Eli Broad had been a force on the boards at MOCA and LACMA, but the relationships were stormy and finally alienating. Broad, a Hammer trustee when Philbin arrived, was instrumental in the school’s sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s 72-page Leicester Codex, the only Leonardo manuscript in public hands, to establish a museum endowment. (Microsoft chairman Bill Gates bought it at auction for $30.8 million.) When Broad then tried to divert a reported $10 million from the sale to a UCLA building project to be named for him, a furious Philbin successfully lobbied the museum board to block him. Broad soon resigned.

Philbin’s aspirations for the museum benefited from its location. Just off-campus at the busy intersection of Wilshire and Westwood boulevards, it has one foot in and one foot out of the school. A high-profile UCLA ambassador in national press, it was also not sequestered from the city. An instant base on which to build came from a wealthy, established Westside art constituency, a good distance from mid-Wilshire LACMA and MOCA downtown.

The UCLA Hammer Museum has been quietly collecting a trove of contemporary art since 2005. But while gallery space has expanded in the last two decades, none is dedicated to permanent display of these contemporary holdings.

Other needs were more complicated to fulfill. Architect Maltzan was engaged to rethink the building, an extensive (and expensive) undertaking that has now gone almost as far as it can.

For programming, Philbin had a vision to make the museum a socially relevant “town hall,” fueled by her past experience in New York with the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), AIDS activist group Act Up and the feminist Women’s Action Coalition. First came construction of the congenial Billy Wilder Theater, home to the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Speakers, panels and films on art, politics and social justice issues appear in hundreds of public programs at the theater annually.

Galleries were reconfigured, the Grunwald Center got a handsome study center, offices were relocated, a restaurant was added, entry orientation shifted in anticipation of a coming subway stop across Westwood Boulevard, and an elegant bridge was built to span an awkward atrium and improve circulation (in a witty gesture, the bridge was named for Tunney). Still to finish: breaking the wall that separates the museum’s reconfigured lobby from new galleries carved out of a former bank branch next door. That final project had to be postponed when the fully funded multimillion-dollar cost was diverted to pay staff support during the COVID-19 closure.

A conundrum: To expand and cement the museum’s growing influence, Philbin launched a contemporary art collection in 2005, joining Grunwald’s impressive holdings in works on paper since the Renaissance and Hammer’s small collection of Old Masters and early Modern art. As yet, however, there are no permanent collection galleries to show substantial selections from among the roughly 4,000 contemporary works acquired so far, and no obvious place to add them.

Generational change is hard; settled habits get disrupted, unexpected possibilities open. Soon, the museum’s profile will look very different.

Change can be resisted, but managing it with skill and optimism is usually a better bet. Philbin is proof. A new director will find challenges, but with much on which to build. Her successor will have an enviable model for how to navigate the next phase.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.