The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

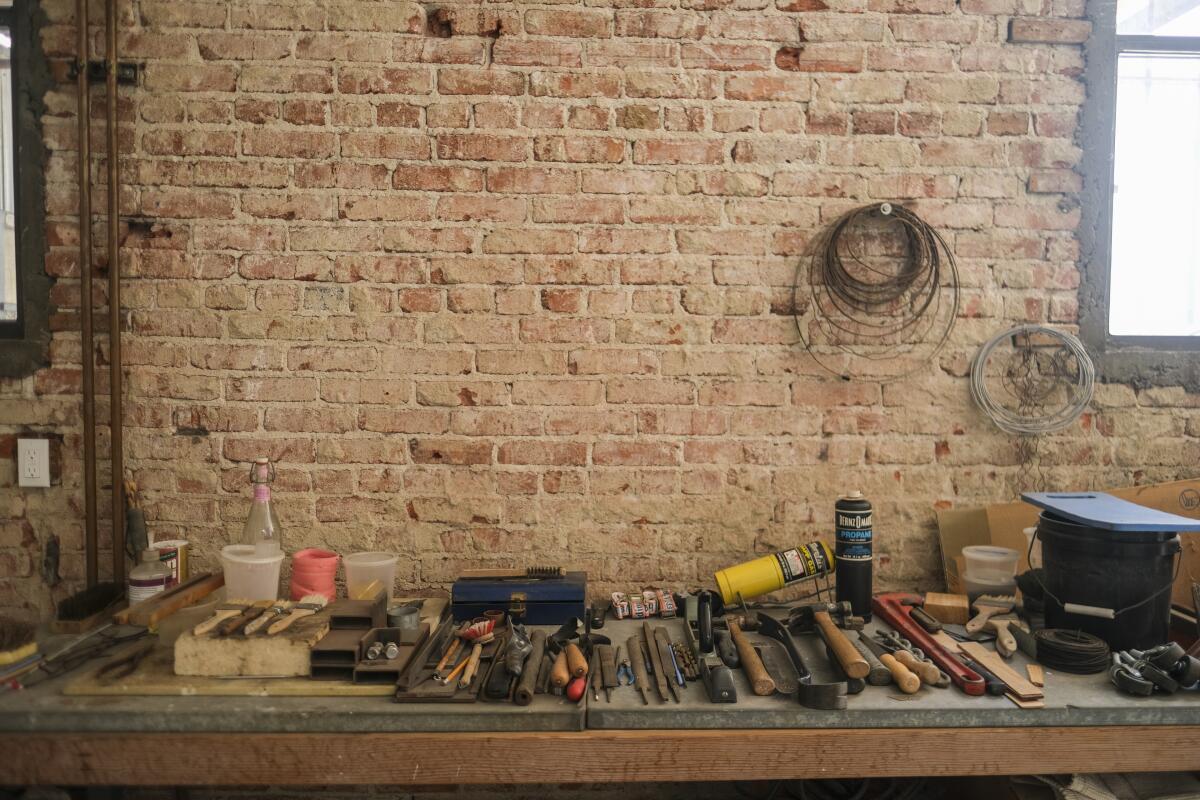

Everything in Luis Bermudez’s studio is just how he left it. On a table lay a trio of sculptures from the artist’s “Memories” series, which carved imprints of snakes into clay, like fossils. Their jagged, winding paths hollow out portions of the gritty ceramic surface. A collection of coiled sake bottles stands in a corner, each tilted and twisted in its own special way. Wooden molds, carefully cut and carved, are clamped together and filed neatly in rows.

Near the studio’s entrance, three photographs, two hats and a pair of sunglasses sit on a pillar. In one photograph, taken at golden hour, Luis poses in his shades next to his windswept poodle, Enzo. It’s an altar to the deceased artist.

In October 2021, Bermudez died unexpectedly at the age of 68. It makes his inclusion in the Hammer Museum’s biennial, “Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living,” bittersweet.

Since his passing, his partner, Karyn Craven, has worked tirelessly to bring attention to Bermudez’s monumental catalog of sculpture. The artist tapped into pre-Columbian mythology, landscape and spiritualism to craft serpentine altars, glistening cenotes and stone portals. He created his own glazes and a formula for castable refractory, a clay compound similar to concrete that withstands high-fire temperatures, to achieve a rugged, organic texture that mimics the volcanic rock found near his grandparents’ ranch in Guadalajara, Mexico.

A master craftsman, Bermudez also invented mold-making techniques, which he passed on to the students he mentored at UCLA, Otis College of Art and Design, Cal State Northridge and Cal State Los Angeles, where he taught for 20 years.

“I just realized how powerful his work is, the magnitude of his legacy, and what he left behind,” Craven says. “You don’t realize it when you’re in it. it’s just your life. This is our studio. This is what we do. We make these beautiful things.”

As a fashion designer, Craven did not know much about breaking into the visual arts, so she tapped into Bermudez’s extensive network of former students. Word eventually reached the Hammer biennial curators, Diana Nawi and Pablo José Ramírez. Without Craven’s outreach, Nawi and Ramírez say, they may never have known about Bermudez’s practice. He hadn’t shown work since 2012, in a group show called “kilnopening.edu” at the American Museum of Ceramic Art in Pomona.

“This is a person who made work for multiple decades and didn’t have a huge critical reception or a huge market. So Luis made work because that was critical to his life and his way of being in the world,” Nawi says.

When Nawi and Ramírez arrived at Bermudez’s West Adams studio, they were shocked to find that he had carefully archived 50 years of work.

“You have this astounding experience where you are seeing such a huge number of works at one time,” Nawi says. “It was such an edifying moment for us both to see the scope of a lifetime of work dedicated to investigating these sets of questions that are formal, conceptual, cultural and material.”

Bermudez worked serially, interrogating an idea — sometimes for decades — until he got it out of his system. The curators picked 14 works of art from four series, a combination of sculptures, wall pieces and vessels. A few pieces come from the series “Offerings,” where unglazed porcelain bowls are juxtaposed with glossy snakes, each conveying a different emotion. Some snakes are molded into realistic forms, while others are flat and best viewed from their profile, like Aztec deities. In “Dangerous Offering,” a cubic, unglazed serpent waits with its mouth agape, ready to snap the hand that reaches into the offering bowl. Tying together historical iconography and universal feelings, the sculptures demonstrate the universality of emotions and how they pass from one generation to another.

Another large influence was nature, which Bermudez absorbed in his travels. Bermudez and Craven saw runes in Iceland, beaches in French Polynesia and temples in Peru. In each of these cultures, people made offerings to deities in glaciers, maraes and cenotes. These unique landscapes would inspire the “Sacred Places” series, where watery glaze shines in contrast to stony, hand-molded castable refractory, which peaks like an island rising from the sea. In his artist statement, Bermudez wrote, “My goal is to empower these objects and communicate to the viewer what I reflect on as the essence of my personal experiences at these sacred or special places.”

Though Bermudez was always producing art, he didn’t prioritize exhibiting in galleries, instead dedicating time to his students. Sean Kelly, who met Bermudez while an undergraduate at Cal State L.A., was first intimidated by Bermudez’s serious nature, precision and strict studio rules. Once, Kelly says he left a hose on the ground, and Bermudez would not let him continue working until he carefully wrapped the hose and put it back in its place. But Bermudez was also sensitive, and had a way of connecting to his students by discussing his philosophy for life.

“It was about being observant or as neutral as possible, and tapping into nature as much as you can,” says Kelly.

“I see Luis as the introduction of meaning to my life,” he adds. “He was a great educator, like the best in my life and other people’s lives too. We shared a complete fascination with ceramics. He taught me that fascination and I immediately absorbed it.”

With Bermudez as his mentor, Kelly would go on to complete his MFA at Cal State L.A. and become Bermudez’s studio assistant. Now, he works closely with Craven to archive and distill the more technical processes of Bermudez’s practice.

“Made in L.A.” will put more attention on Bermudez, and Craven hopes to channel the enthusiasm into a nonprofit that gives back to the community. The studio, which is robustly built out with kilns, ventilation, storage and an outdoor work space, could become a center for underserved communities to learn ceramics, or for visiting artists.

“When something is included in something so public, it becomes part of the canon and part of the vocabulary of what’s happened and what’s been happening in Los Angeles,” Craven said. “I feel like the time is right for Luis’ work. It’s right for Luis’ story.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.