Mt. Wilson is around an hour’s drive from downtown Los Angeles. But when you get there, it can feel like you are on the forest moon of Endor. With its clusters of spiky radio tower spires and stark white observatories nestled among tall pines, any Ewok would feel at home.

George Lucas didn’t film “Return of the Jedi” in Angeles National Forest — for that he chose the otherworldly scale of Northern California’s redwoods — but sitting atop a 5,710-foot peak, Mt. Wilson’s telescopes do draw the eye and imagination toward the cosmos.

It’s an ideal location to stage a sci-fi opera about a crew of human astronauts and the telepathic alien they encounter a long time from now, in a galaxy far, far away.

“Star Choir,” an “interstellar chamber opera,” will be presented by L.A.’s acclaimed experimental opera company the Industry inside Mt. Wilson’s largest observatory on Sept. 30 and Oct. 1. The opera features eight singers and six instrumentalists (horn, harp, synthesizer, cello, contrabass and percussion) and is the brainchild of Malik Gaines, the Industry’s co-artistic director, and his life partner and artistic collaborator, Alexandro Segade.

With a creative team of Native, Chinese and African American artists, ‘Sweet Land’ revisits the founding of America through a different lens.

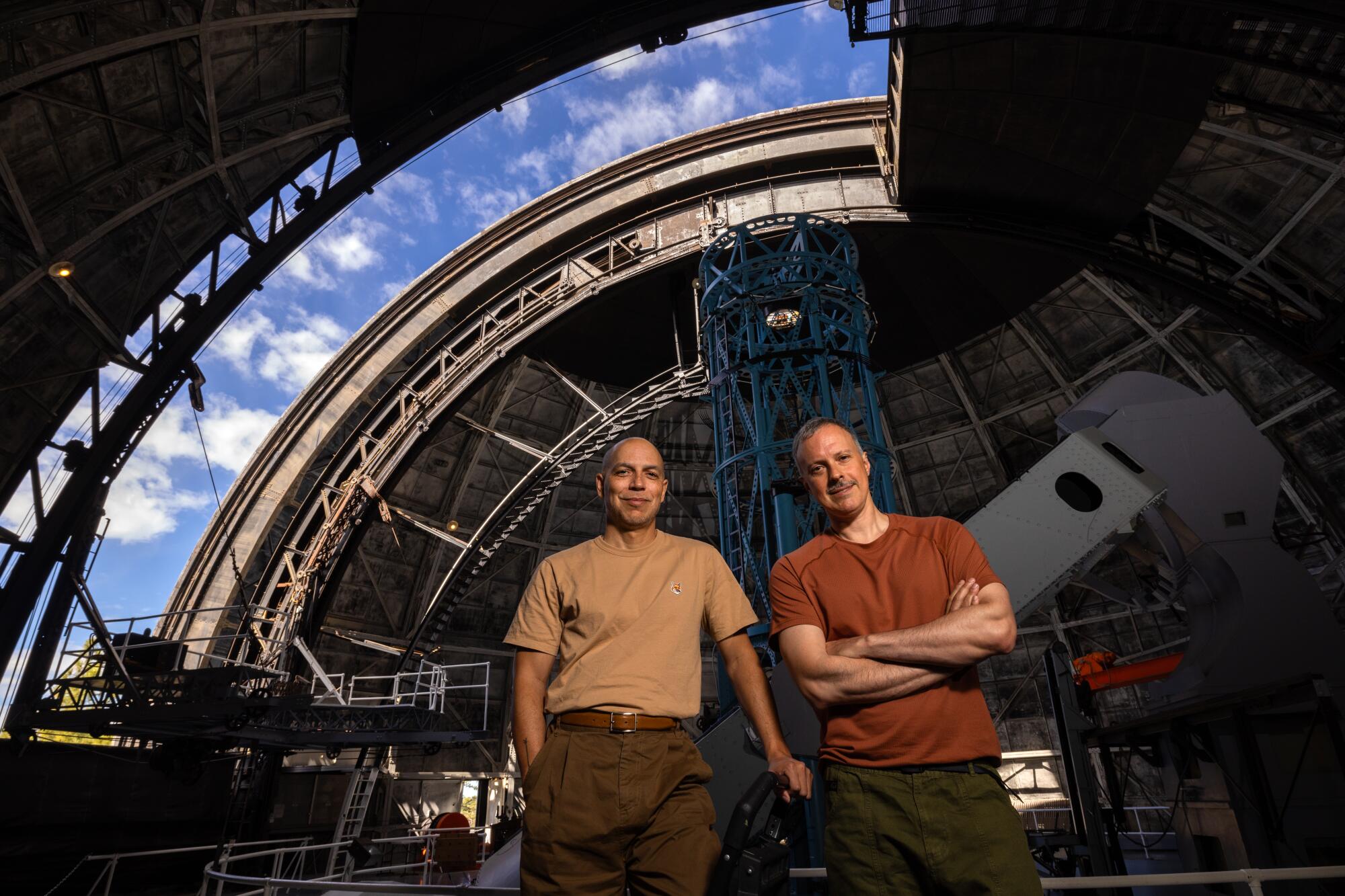

On a recent morning, Gaines — who composed the music for “Star Choir” — and Segade — who wrote the libretto — sat down for a chat inside the dome, the massive white structure that houses Mt. Wilson’s 100-inch telescope.

“The first impulse [might be to] do projection mapping, put stars all over this,” Segade says, gesturing up at the observatory’s expansive domed ceiling with exposed metal scaffolding. “But look where we are. Why cover it up with some other thing? We want to just work with it to create the ambiance. We are looking at Ridley Scott’s ‘Alien’ to get ideas about how to light a space like this.”

The dome is a dark, cavernous time capsule that features century-old technology and machinery, not unlike the interior of famous cinematic spaceships. Rather than hiding this infrastructure, “Star Choir’s” creators incorporate it into the action of the opera.

During key theatrical moments, the elevated observation platform on which an audience of around 200 will be seated will slowly rotate. At other moments, an apparatus will be activated that opens a slice of ceiling to the bright blue sky, flooding the improvised stage with daylight.

“We went on a search, and we found this place, and it kind of had to be here, with all of its difficult sightlines,” Gaines says.

“And difficult acoustics. Difficult to get to,” Segade adds.

“It’s so beautiful,” Gaines says.

“That’s why it’s worth it,” Segade agrees.

Gaines and Segade speak in a fluid, telepathic cadence that reflects decades of intimacy. The two met as freshmen at UCLA in 1991 and have been together ever since. Segade, who celebrated his 50th birthday earlier this year, grew up in San Diego. Gaines is from Fresno and will turn 50 in December.

The experimental opera company behind ‘Sweet Land,’ ‘Hopscotch’ and ‘Invisible Cities’ turns the artistic director position into a cooperative.

The couple recently returned to their home state after a 10-year stint in New York City, where they expanded their artistic networks and horizons. Today, both teach in the visual art department at UC San Diego. They share a downtown San Diego high-rise that Segade describes as eliciting the “sexy dystopia” vibes of a J.G. Ballard short story. “We’re looking for a new place,” he adds.

Before they moved to New York in 2011, the couple spent many years in Los Angeles, where they still maintain a studio and where, in 2000, they formed the influential performance art collective My Barbarian with Jade Gordon.

Armed with hand-made masks and a campy, DIY aesthetic, My Barbarian’s performances engage audiences through musically driven theatrical works that offer sharp political and artistic critiques. The group has performed in black box theaters and white box galleries — their work was the subject of a recent Whitney Museum of American Art retrospective that also went on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, L.A. last year — but their aesthetic feels suited for more unconventional spaces.

When the Industry, a company renowned for staging operas in train stations, public parks and other inventive locations, invited Gaines to co-lead the troupe alongside sonic artist Ash Fure and founder Yuval Sharon, “Star Choir” was already in the works.

Envisioning the work as an opera, Gaines was excited by the prospect of writing music for professional singers and musicians and removing Segade and himself from the performance, a shift from their work as My Barbarian.

Gaines and Segade began dreaming up an interstellar musical theater piece in 2016. At the time, Segade was co-chair of the film and video MFA program at Bard College in New York and Gaines was in residence at the Headlands Center for the Arts just north of San Francisco.

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

The pair had recently been invited by the L.A.-based arts and culture nonprofit Clockshop to study and respond to the archives of Pasadena-native Octavia E. Butler’s works, which are stored at the Huntington Library.

“Star Choir” originated as a theatrical attempt to fill in the blanks of Butler’s unfinished novel “The Parable of the Trickster,” the planned third installation in her lauded 1990s “Parable” series. As is typical of their artistic process, Segade kicked things off with text.

“I remember looking out into this field [at Bard] and looking at a deer and thinking, ‘That’s the most beautiful thing in the world, and it is covered in ticks.’ Like, this is the universe,” Segade says. He drafted some poetry on the subject and shot it off to Gaines in California to set to music.

The narrative of “Star Choir” evolved over time, and the music that Gaines compiled is eclectic. When writing for the humans in the story, Gaines says he incorporated earthy folk rhythms and catchy tunes. “The stars are kind of out there with weird time signatures and complicated harmonies. The allergens are really spacey. When the molecules themselves sing, wow, things get kind of atonal,” he says.

When Gaines was a little boy in Fresno, his father, artist and educator Charles Gaines, took him to see his first movie — ”Star Wars.” “I remember trying to understand it, but also being into it,” he says.

Today, he is still into it. And now he understands the power and complexities of science fiction from a storyteller’s perspective, the way it allows us to escape reality and grapple with it. “Without conventions of realism, you can speculate much more freely,” he says. But even when fictional humans visit distant galaxies, they encounter human problems.

“The questions that science fiction is able to address are, ‘What does it mean to be human?’ and ‘Why do we even want to be human?’ That’s the big question we’re asking,” Segade says.

It’s a question both artists say is worth contemplating through art, in person, collectively. Worth years of researching and creating and workshopping. Worth the winding drive up a big mountain. Worth considering, if only for an hour or so, our place in the universe.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.