‘Disney Lorcana’ aims to shake up the trading card game space

When Ryan Miller first played “Magic: The Gathering” he was hooked. It wasn’t long before the Bakersfield teen was attempting to design his own collectible card games. Early experiments were disastrous.

“Here’s this new style of game,” says Miller of “Magic,” which was first released in 1993. “I’ve gotta try this.”

So he invested in 3-by-5 note cards, cut them in half and began creating his own characters. The goal? A dueling swordplay game. “I was going to do a fighting game. My brother eventually stopped playing. He’s like, ‘The game will never end, dude.’ It was too easy to block attacks. And to me, that felt like we were sword fighting. I’m parrying! But at the end of the day, there was no forward progression. That was my first lesson. This type of game is really hard to design.”

There would be others. Miller today is eloquent in describing the intricacies involved in designing a card game such as “Magic.” A game design veteran who eventually found his way to “Magic” parent Wizards of the Coast, Miller’s path wasn’t direct, and included time spent as a prison guard. Today, however, he’s overseeing the launch of what has been described as the most anticipated collectible card game to arrive in years, one that already seems poised to take its place alongside “Magic” and “The Pokémon Trading Card Game” as a pillar of the medium.

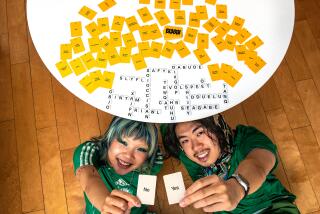

Ravensburger’s “Disney Lorcana” launched earlier this month at a limited number of hobby shops before its wide-release in early September. Though it hasn’t arrived without some legal controversy, it appears to be an early hit, at least if the crushing lines it causes at game conventions are any indication, with fans waiting hours to get their hands on product and promotional cards. “Lorcana” taps into Disney’s storied animation history, as players will use cards to accrue ink, which can conjure images of popular characters, objects and songs, all in a quest for what the game defines as “lore.”

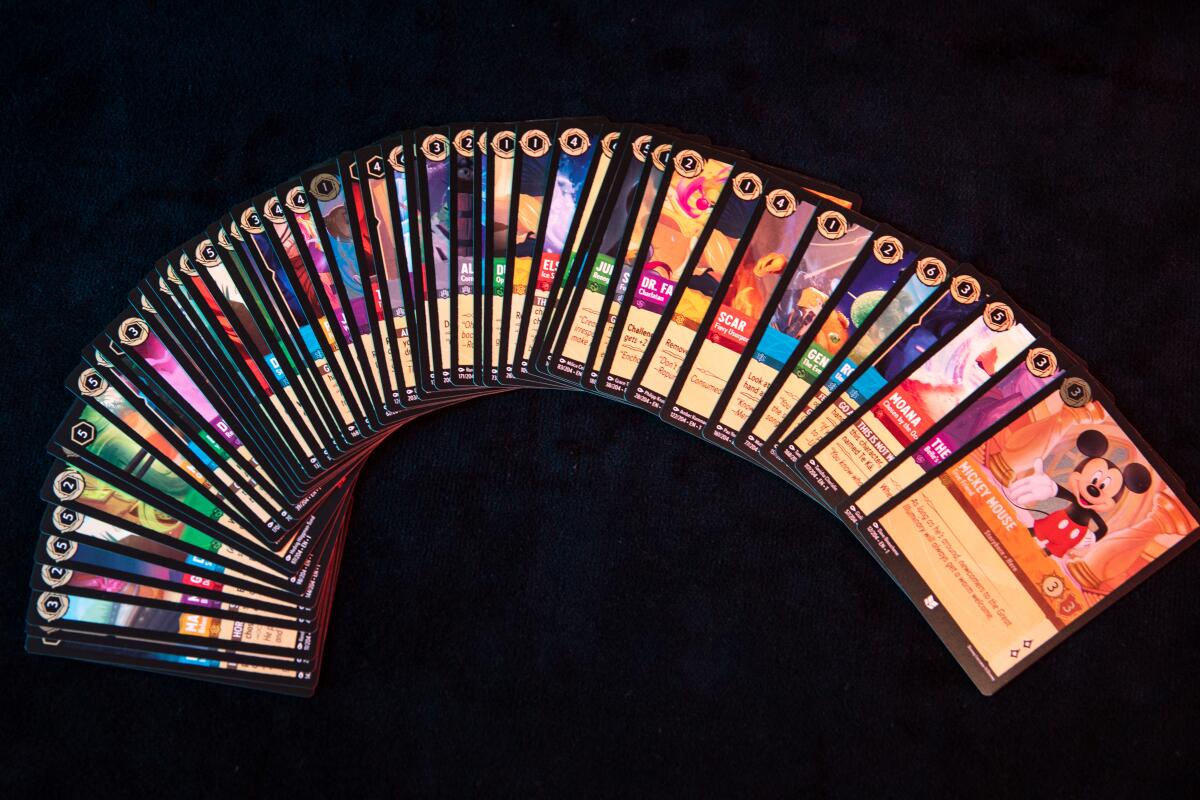

“Lorcana” is also the first collectible card game from longtime tabletop firm Ravensburger, known already among the Disney fan community for its “Villainous” line of board games. “Lorcana,” with its mix of recognizable as well as unexpected characters and objects — Anna and Elsa from “Frozen” will duke it out with Sergeant Tibbs from “101 Dalmatians” and all eras of Mickey Mouse — aims to play with our nostalgia as much as it does game mechanics, as cards will reference signature Disney weapons (a frying pan) with recognizable songs (“Hakuna Matata,” “Friends on the Other Side”).

For Miller, it represents a lifetime of attempting to merge the impressionistic storytelling of collectible card games with relatively fast-paced, approachable gameplay. “Card games have a level of abstraction,” Miller says. “You can feel a story kind of unfolding. In ‘Lorcana,’ one of my favorite mechanics is the song mechanic. You can have one of your characters sing for you. It’s a great example of how cards can show you a little scene that’s happening. When two characters challenge each other, I like to think that maybe they’re not fighting; maybe they’re just arguing. The nice thing about that abstraction is that instead of telling the player, ‘Here is what is happening,’ they get to bridge that gap.”

For the game industry, it’s hoped for as a potential blockbuster. “Quite simply, the launch of ‘Disney Lorcana’ is the largest, most buzzed-about customizable trading card game launch that we’ve seen in several years,” says James Zahn, editor in chief of trade publication the Toy Book. “This is a space that is largely dominated by existing game platforms such as ‘Magic: The Gathering’ and ‘The Pokémon Trading Card Game,’ and ‘Lorcana’ has the opportunity to connect with players who are familiar with that type of customizable gameplay, but also attract this entirely untapped fandom of Disney enthusiasts.”

“Lorcana” is coming to market despite a lawsuit that attempted to stop its release. Trading card and game firm Upper Deck this summer sued Ravensburger for what it blasted in a release as a “stolen game,” alleging essentially that Miller, while on a work for hire contract with Upper Deck, developed the game that would become “Lorcana.” The breach of contract suit contends that an Upper Deck game bears “remarkable, uncanny similarities” to “Lorcana.” Miller, the co-designer of “Lorcana” with Steve Warner, declined to address the lawsuit.

Ravensburger has sought to have the case dismissed. “We at Ravensburger stand behind the integrity of our team and the originality of our products,” reads the company’s official statement.

While the lawsuit goes to great lengths to show the ways in which “Lorcana” resembles the as-yet-unreleased Upper Deck title, game mechanics, generally, are not protectable by copyright law. “They are rules, processes and mechanics that aren’t on the same level as a song or a painting,” says attorney Zachary Strebeck, who works primarily in the game space. “They protect creative work and not underlying functionality. It’s unfortunate for games. There is plenty that’s copyrightable in the game — all the artwork, and the way it’s written — but not the underlying rules themselves.”

Thus, Upper Deck, if the case proceeds, is arguing a breach of contract and fiduciary duty. The company declined to comment beyond its official statements to the media. Yet the high profile of “Lorcana” has attracted a fair amount of attention and speculation to the case. “Anytime you wind up with a situation where a new product is developed by a former employee of someone else in that space, eyebrows get raised,” says Zahn, who notes the case isn’t dulling anticipation for “Lorcana.”

Ravensburger’s global head of games, Filip Francke, says the company’s creative attention has not been diverted. “Throughout this whole time, we have tried to keep our eyes on the ball,” says Francke. “Eyes on the ball means we’re following our plan. ... We didn’t want to get distracted by anything — lawsuits or anything else.”

If the allegations are stressing Miller, it isn’t apparent. He’s eager to demo the game and discuss how “Lorcana” cards dig deep into Disney’s animation vaults. The ways, for instance, different cards from “Sleeping Beauty” will accentuate distinct aspects of Princess Aurora’s personality, or how “Lorcana” consistently pulls from unexpected places — one card, for instance, may reference the tabard from the Mickey Mouse-starring “The Three Musketeers,” and another may simply point to the Beast’s ability to throw a tantrum. Anything in a Disney animated short or film is fair game, and it will need to be, as Francke says Ravensburger has 10-plus-year road map for “Lorcana.”

The trick was creating a game in which players could interact with as many cards as they desired — if someone wants, for instance, a princess-themed deck, Miller wanted “Lorcana” to accommodate that — while creating a cohesive game that still felt family-friendly and readily approachable. Many experiments were attempted and discarded, including an early version that had “Lorcana” feeling more like what Miller describes as a “coding game.” Another tried to play up a good-versus-evil bent.

“I had this crazy idea — what if villains could only challenge heroes and heroes could only challenge villains?” Miller says. “It was very thematic. That’s a good example of wanting immersion at the gameplay level, and how the best intentions could crash and burn. That game was not very fun. You could build a deck that has half and half, but what if you don’t draw enough villains? Then you just can’t interact.”

Miller joined the project about six months in, and says it took about another six months to reach a gameplay loop that the team felt comfortable with. Then it was about three years of iterating based on the different actions cards could inspire. At times, “Lorcana” will feel familiar to anyone who has dabbled in “Magic,” but its Disney animation focus allows it to pull from friendlier — and sometimes sillier — themes. There’s plenty of swords and sorcery here, courtesy of Disney’s wealth of fantasy material, but there are also cards of coconuts and songs such as “Be Our Guest.”

“If we innovate the trading card game rules, the trading card gamers get super jazzed about that, but we risk alienating folks who have never played a trading card game before,” Miller says. “If we go way too safe, we risk the other thing, where the trading card gamers say, ‘This isn’t for me.’ I think the reason it took so long to get where we got was that specific target we were trying to hit — to do something that we feel is welcoming, and strategically exciting for trading card gamers.

“The trading card platform does this very well,” Miller continues. “The game itself needs to support inputs — cards. The game design is like the frame of a house, and it just needs to support a beautiful roof and wonderful walls and this furniture. What I mean by all that is the frame can be fairly welcoming, but the strategic depth comes on how you decorate it. That comes on the cards.”

The heroes-versus-villains idea, while it didn’t work, would have been nice symmetry with Ravensburger’s Disney tabletop game “Villainous,” which the company has stated has sold more than 1 million copies globally. But while Ravensburger was entering the collectible trading card space for the first time, Francke says the company leaned on its lessons from “Villainous” in making “Lorcana.” Namely, keep it simple.

“You’re playing the path of a specific character,” Francke says of “Villainous.” “So you’re trying to make the evil deeds that the character does, and then you play the good guy toward your opponent. I think there was an immediate understating of what the game is about. The Disney license makes it easier for people who normally don’t play these games to think that it’s familiar in some way, even if they don’t know the gameplay. That helps the accessibility, but I think the game came out, to some extent, a little more difficult than we wanted it to be. If you’ve never played a board game before, it is a little bit of a journey to get into. So we took some learning from that. Can we make something more accessible?”

Miller was brought into the fold in part because he’s been a longtime student of the collectible trading card medium. Before working his way up the ranks at Wizards of the Coast — starting at the company in a more promotional aspect more than 20 years ago — he honed his game design skills as a member of the military in the late ’90s. His career trajectory was one that was going to take him into law enforcement, but before committing he sought to pitch himself as a game designer.

“I was a prison guard at Fort Leavenworth,” Miller says. “And that line of work is 98% boring and 2% terrifying. I still to this day have books from that period where I’m listing out ‘Magic’ decks I want to make, or I’m working on my own ideas for trading card games.”

A “Warhammer 40K” trading card game that Miller co-designed in 2001 with Luke Peterschmidt has roots in that era. “The bones of that game are in those notebooks from the mid-’90s. I loved ‘Warhammer 40K’ but I couldn’t afford the miniatures back then on a soldier’s salary. And the more I started coming up with the ideas, the more it was exciting to me. Military police in the Army was my goal, but as I was leaving the Army, I decided to give [game design] a shot and go to Seattle where Wizards was based out of.”

He hasn’t left the game space since. But when pressed to think about his game design philosophies, Miller concedes that with “Lorcana,” in a way his career is becoming full circle. His first memories of play were not with dice and a board but with Anaheim’s Disneyland Park.

“Growing up in Bakersfield, kind of on the poor side, my grandmother would occasionally take me to Disneyland,” Miller says. “And immersion is the No. 1 feeling I get from Disneyland. You walk on Main Street, U.S.A., and you’re transported. You hang a left, and you go in Adventureland and all of a sudden you’re in a jungle. It impressed upon me the power of immersion.”

They were lessons he would recall when he discovered hobby games. “That’s one of the reasons it engaged me. That concept of decision immersion — of putting myself in a role of someone in that world — was a big part of getting into gaming. You can immerse someone by the environment, and the types of decisions they have to make. Suddenly I’m making a decision that someone wielding a sword in a dungeon might have to make, or someone piloting a 40-foot-tall walking robot might have to make. “

Or in the world of “Lorcana,” when to throw down a Maleficent, or when to conjure a romantic ballad.

The Batman game ‘Arkham Asylum Files’ comes from those in the theme park space. ‘Mother of Frankenstein’ is from escape room masterminds Hatch Escapes.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.