Artist Gala Porras-Kim wants to know: ‘Can a museum be a cemetery? Or a Crate & Barrel?’

It’s unclear why the Fowler Museum has a bag of unidentified debris in its possession. The crumbled morsels and small specks are light brown, contained in a clear plastic preservation bag. A handwritten sticky note is on the bag, imploring someone to assign a number to it, but there’s no indication of what the stuff might be.

Gala Porras-Kim, a contemporary conceptual artist, believes these might be bread crumbs. The Fowler was established in 1963 at UCLA and has more than 150,000 objects in its permanent collection and 600,000-plus in its archaeological holdings, with origins spanning Africa, Asia and the Americas. So the crumbs could theoretically be from some ancient loaf, bread broken at one of the most consequential meals in history. Or something else entirely.

For Porras-Kim, this is not merely the kind of oddity one would find rummaging through any major museum’s holdings. “The weight of a patina of time,” her new exhibition at the Fowler, includes a selection of her projects from the last seven years. There are reproductions of ancient objects, written proposals to museums and actual artifacts from the outer edges of the Fowler’s collection.

Born in 1984 in Bogotá, Colombia, and currently living between Los Angeles and London, Porras-Kim cuts a figure between academic and trickster. Her work, shown at venues like the Whitney and São Paulo biennials, includes sculpture, installation and scholarship.

Probing the ethics and practical concerns of how institutions acquire, conserve and display cultural artifacts — with a special attentiveness to the bureaucratic maze that funnels this material — Porras-Kim often collaborates with the institutions themselves. Her subjects have included the British Museum’s enormous collection of ancient Egyptian and Nubian funerary art and the evolution of how scholars (mis)understand ancient undeciphered languages. The seriousness of her inquiries is complemented by a playfulness, nudging people to think more subtly about the repatriation of ancient objects and the role of institutions as both caretakers and current-day repositories of colonial holdings. She wants to know, “Can a museum be a cemetery? Or a Crate & Barrel?”

Besides the purported bread crumbs, Porras-Kim’s exhibition includes ceramic shards that were found inside an intact ceramic vessel, donated to the Fowler. Among these broken, unidentifiable pieces was a plastic collar stay, the present-day kind inserted into a shirt collar to keep it straight. Originally appearing in her contribution to the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” 2016 exhibition, Porras-Kim imagined what these fragments may have once been a part of. She sculpted a vase with the shapes of the shards cut out, and if you look closely, you’ll see the shape of the collar stay as well. She then penciled a scaled sketch of the imagined reconstruction, like an archaeologist would. “Because the institution says [the collar stay] belongs to this bag, it’s an antiquity now,” the artist says.

Matthew H. Robb, chief curator at the Fowler and curator of “The weight of a patina of time,” bristles a bit at Porras-Kim’s suggestion that the plastic garbage is now an antiquity because it’s in the same storage bag.

Robb and Porras-Kim’s dialogue and collaboration started in 2016. Spectacled and erudite, Robb is one of the foremost scholars on Teotihuacan, the ancient Mesoamerican site containing the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon. In 2017, Robb curated the exhibition “Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire,” showcasing new objects found at the most archaeologically significant — and one of the most touristic — sites in the Americas. Porras-Kim was drawn to two massive stones, which were discovered inside the top of the pyramid using Lidar technology. “It took a lot of energy for someone to put these rocks in the top of the pyramid, all enclosed with no door or anything — for what?” Porras-Kim asks. “There’s a purpose for these rocks that we don’t know.”

In 2018, she wrote to the national coordinator of museums and exhibitions at Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, asking for permission to replicate the stones. The replicas stand in the Fowler gallery, imposing, smooth, mute. Robb has said the mysterious stones may have been something like the spiritual batteries of the pyramid. Porras-Kim then proposed reinserting them into the top of the pyramid but was turned down. Now she wonders if her replicas change the role of the institutions they travel to.

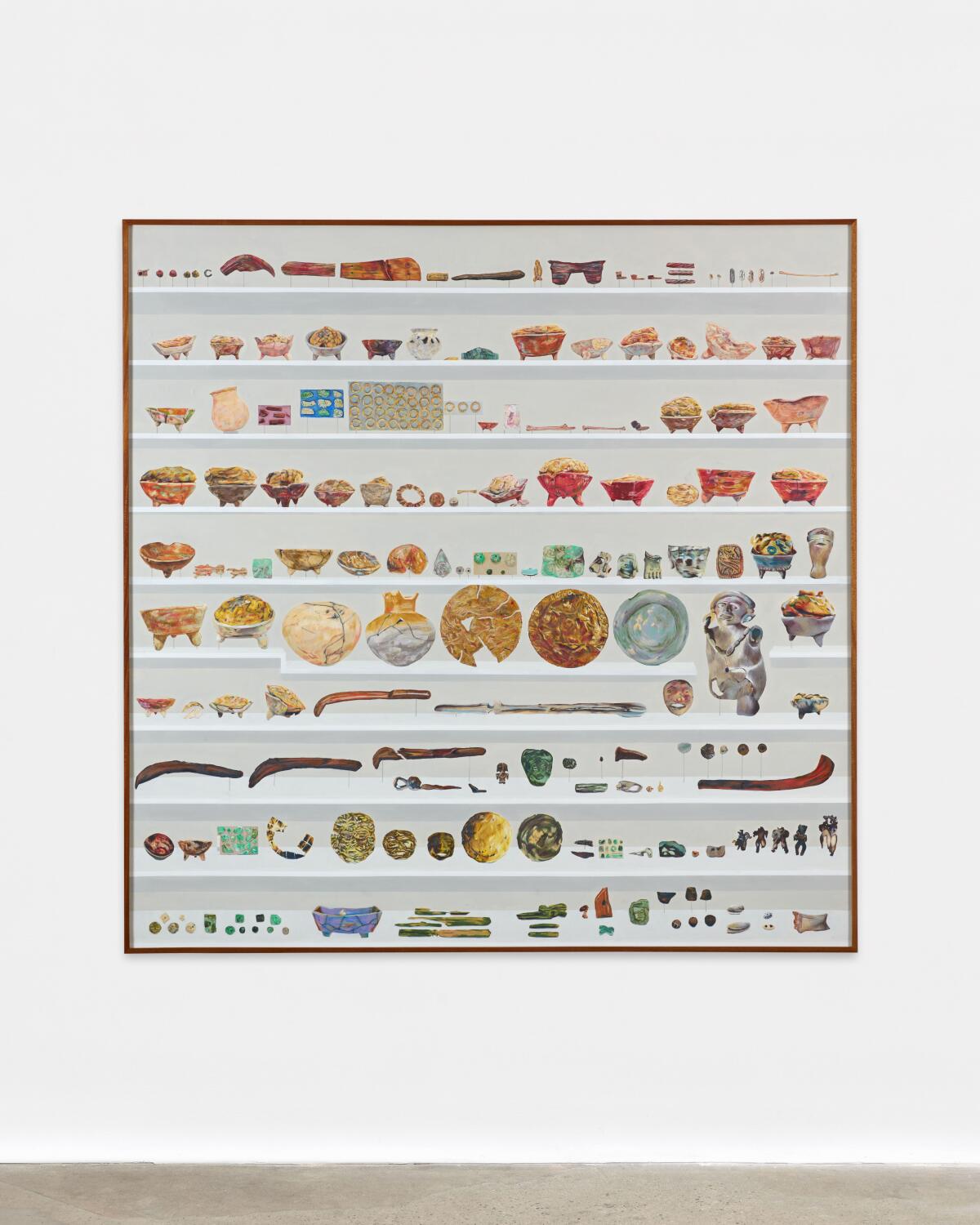

Another of Porras-Kim’s works on display, “254 offerings for the rain at the Peabody Museum” (2021), is an elegant index drawing in colored pencil, rendering 254 of the 30,000 objects taken from the cenote at Chichén Itzá, a sinkhole sacred to the Maya people, considered a portal to the spirit world. Today it’s a popular swimming spot for tourists.

Heirloom jade objects, bundles of copal (incense made from pine resin) and gold discs portraying battle scenes were just some of the objects tossed into the cenote, perhaps as offerings to the Maya rain god Chaac. The objects were excavated by archaeologist Edward H. Thompson, who owned the cenote in the early 20th century. Porras-Kim has tracked these objects — some of which remain in the collection of Harvard’s Peabody Museum, some of which have been sent back to museums in Mexico — and her goal is to index every single one. “Gala’s drawings are the best, most comprehensive public record of what each institution holds,” Robb says.

Beyond the indexing, Porras-Kim and Robb want people to think about how institutions relate to their collections as caretakers and the nuanced complexity of repatriating objects such as these. One of the jade heads found at Chichén Itzá, for instance, was perhaps itself looted from Piedras Negras, then brought to the cenote. “When a quote-unquote ‘repatriation’ happens, the likelihood of an object going back to exactly where it came from is vanishingly small,” Robb says. It’s far more complex than simply sending items back to their country of origin.

The Fowler, which received a collection of 30,000 objects from British pharmaceutical entrepreneur Henry Wellcome in 1965, has been reviewing the collection’s provenance for several years. The museum “has confirmed a small number of unethically acquired objects and belongings of critical cultural importance,” says Erica P. Jones, senior curator of African art and manager of curatorial affairs, “all of which have entered a multistage process of return to their community of origin.” This includes six objects looted from Benin’s Royal Palace by British colonists in 1897.

Rather than objects with a clear cultural heritage, such as these, for “The weight of a patina of time,” Porras-Kim and Robb searched the Fowler’s collection for more modern artifacts that have baffled conservators and curators.

“Gala and I were poking around in there and took some of the boxes off the shelves,” Robb says. “It was the weirdest stuff.” The artifacts are simply on display, without any accompanying artwork by Porras-Kim. One object is an issue of an old newspaper from 1959 — aptly titled Empire News — which contains an unknown item inside. The paper is so old that it would crumble if unwrapped, resulting in the destruction of what is a historic object in its own right.

The duo also found a box labeled “Mesoamerican & South American Archeological FAKES.” Presented on a metal storage shelf, the sculptures of unknown provenance are wrapped in individual plastic bags: dog-like creatures, figurative pipes for smoking and Modernist-looking decorative objects. They were purchased at an auction in 1928. If indeed “fakes,” it’s unclear what they are trying to mimic. “It’s like somebody’s trying to figure out a kind of Neoclassical, ancient Mexican, Art Deco kind of vibe,” Robb says. “You can’t be a pre-Columbian specialist and just be like, ‘Well, this isn’t an ancient thing, so I’m just gonna consign it to the fake shelf.’ Somebody made this object — and we actually don’t know their intentionality.”

“The weight of a patina of time” is ultimately about what we don’t and will never know about the past. As Robb says of Teotihuacan, still the subject of raging debates about its purposes and functions, “Just because something is gigantic doesn’t mean it’s going to hold or maintain its meaning.” For a work titled “Frass Monochrome” (2023), Porras-Kim asked Robb to collect some frass — the excrement of insects, moths in this case, that have eaten through parts of the collection — from the storage of the Fowler. The artist then framed the stuff, gesturing that time itself is a material and that the audiences for museum objects aren’t only human.

In a thousand years, what conclusions will be drawn about the Fowler Museum and the innumerable things it contains? Maybe someone, or something, will finally discern the provenance of those crumbs.

'The weight of a patina of time'

Where: Fowler Museum, 308 Charles E. Young Drive N., Westwood

When: noon-5 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays. Through Oct. 29.

Info: (310) 825-4361, fowler.ucla.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.