Column: Adamant and argumentative, SAG-AFTRA plays new role in Hollywood strikes: the heavy

You want to know how tense it is in Hollywood right now? SAG-AFTRA is turning out to be even more argumentative and aggressive than the WGA.

Less than three weeks after guild president Fran Drescher rattled C-suite windows with her fiery announcement of an actors’ strike, the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists is already roiling with internal arguments over whether even independently produced work should get done, while Drescher insists that the guild is prepared for the strike to last six months.

So much for bad guild/good guild.

Historically the guild most ready to brawl, the Writers Guild of America went out on strike in May. A month later the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents the studios in labor negotiations, quickly came to an agreement with the Directors Guild of America.

With writers and actors on strike, the studios have a full-blown labor revolt on their hands — and they have no one but themselves to blame.

Many in the entertainment industry believed the AMPTP would contain what was increasingly being called “hot labor summer” by following that up with a reasonable new SAG-AFTRA contract.

Then, if the WGA chose not to follow the template of this imagined actors’ contract, writers could picket ’til they dropped. A few studio executives were even brash (or stupid) enough to brag, anonymously, about their determination to let the strike go until writers lost their homes. (The AMPTP denied this was the actual strategy.)

For a few minutes, it seemed to be working; as the June 30 contract expiration deadline neared, Drescher and SAG-AFTRA National Executive Director and chief negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland sent out such optimistic messages that some members complained that the guild wasn’t playing hardball.

But after giving the studios a two-week extension, Drescher called for a strike.

Now the AMPTP appears to think its best bet may be the WGA after all.

On Tuesday, studio representatives reached out to the Writers Guild requesting a meeting, the first since negotiations broke down three months ago.

Instead of using the actors to bring the writers to heel, as many had predicted, the studios seem to be flipping the script.

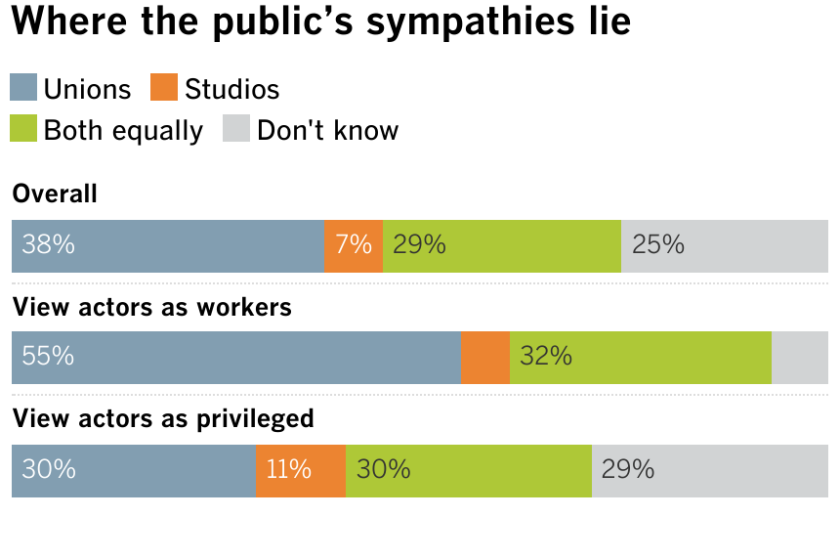

Emphasis on seem. Requesting a meeting doesn’t mean the studios are willing to make concessions — it could just be an attempt to get a bit of good PR, which the AMPTP certainly could use. According to a recent survey conducted for The Times by a Canadian polling company, far more Americans sympathize with the actors and writers (30%) than with the studios (7%).

SAG-AFTRA approved side agreements allowing more than 100 independent film projects and series to move forward amid the strike, but the deals have spurred debate.

Try as Bob Iger and other entertainment media CEOs might to paint the striking writers and actors as unrealistically demanding money from a dried-up faucet, their own executive pay scale, healthy quarterly reports and, in the case of “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer,” booming box office make it a bit difficult to swallow.

Try as the studios might to pooh-pooh the possibility of artificial intelligence taking over work formerly done by writers and actors, their own high-level AI-related job postings give them away.

There is simply no narrative in which the AMPTP appears to be the injured party, especially with so many writers and actors breaking Hollywood’s time-honored code of silence to share their often surprisingly low salaries and studios’ requests to body-scan them.

With any luck, the studios are at long last realizing this.

The WGA may be considered the prickliest guild in Hollywood, but after Drescher called out entertainment execs, often by name, using terms like “greedy” and “land barons,” the studios may be thinking prickly is not too bad.

The writers have, of course, been on strike far longer. After three months, their financial situations are growing more dire; despite the hackles raised by out-of-touch comments by studio brass, the AMPTP may think the writers are more ready to deal.

And that the actors would follow the writers’ lead should the WGA come to an agreement with the studios.

Perhaps. SAG-AFTRA is, after all, already showing signs of inner turmoil over the handing out of interim agreements that allow independent production companies to work during the strike.

A new L.A. Times poll on Hollywood’s double strike finds the public is more likely to support striking actors and writers than studios and streaming services. But many express ambivalence.

As my colleagues Meg James and Wendy Lee reported on Thursday, many strikers are unhappy that the actors’ guild is allowing independently produced films, many with A-list stars, to proceed as long as the producers agree to the union’s final proposal to the studios.

Representatives have said this bolsters their position by disproving AMPTP’s argument that increased pay and better residuals will bankrupt Hollywood. But some actors, and writers, have expressed outrage at the more than 100 interim agreements that have been issued so far.

As Sarah Silverman and others have argued, allowing some people to work while others are on strike sends a less-than-unified message and ignores the economics of the industry — most independent films will wind up on a streamer one way or another. When Viola Davis recently announced she would not move forward with her next film, despite getting an interim agreement, she was celebrated by many strikers.

The interim agreements also give film an out that is mostly not available to television (the Apple TV+ series “Tehran” got one because it is an international production that follows international labor laws). As this strike is, in large part, about streaming, the optics of separating one art form from another are awkward at best, especially given the hyphenated nature of the organization’s history; the SAG-AFTRA marriage is only 11 years old.

Indeed, in the wake of the 2007 writers’ strike, SAG and AFTRA were often at loggerheads, clashing over who controlled television contracts, with the larger SAG criticizing and blocking AFTRA’s early attempts to make a deal.

This is, in fact, the combined organization’s first big strike; all things considered, pushback over interim agreements may not be that big a deal.

Nor is it unheard of, historically. David Letterman famously was able to bring his writers back to “Late Night With David Letterman” and “The Late Late Show” in the middle of the 2007 writers’ strike because his production company owned the shows and agreed to the WGA’s terms.

In this year’s strike, however, no such side deals have been made with the WGA and thus far the conflict over interim agreements has not affected the picket lines or SAG-AFTRA’s resolve. When asked on “Today” how long she thought the strikes would last, Drescher said “We have financially prepared ourselves for the next six months. And we’re really in it to win it.”

Television’s most recent ‘Golden Age’ set off a gold rush that transformed Hollywood. The writers’ strike means the boom has finally gone bust.

During a meeting with publicists concerned about strike rules that forbid actors from doing publicity, Crabtree-Ireland told them, essentially, that this is what an actors’ strike looks like and that there would be “collateral damage.”

This did not, understandably, go over very well. Many publicists barely survived the COVID-19 shutdown and they are just one portion of the millions of entertainment industry and industry-adjacent workers currently suffering from strikes in which they had no vote. One strong argument for interim agreements is that they allow not just A-listers but the hundreds of other members of a film’s cast and crew to go back to work.

But the excitement over the AMPTP reaching out to the WGA serves as an important reminder that the unions did not cause the strikes.

The studios’ refusal to meet long-anticipated demands for contracts that address the changes streaming has wrought in a way that allows actors and writers to earn a decent living in their chosen profession is what caused the strikes.

So any complaints should be addressed to those who occupy the buildings behind the picket lines.

It would be terrific if the AMPTP is finally ready to do what it should have done months ago if only because it is the organization’s actual job.

If, having seen a hoped-for SAG-AFTRA détente blow up in their faces, the studios want to start with the writers, great. But as Jennifer Lawrence said in “Silver Linings Playbook” (as written by David O. Russell), if it’s me reading the signs, they had better know that, at three months or three weeks, neither strike is going to end unless a serious deal is offered.

Because the WGA is not the only union in town that’s ready to brawl.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.