Review: A Getty show of Giacomo Ceruti’s 18th-century paintings reveals much about our modern wealth gap

The unconventional 18th-century Italian Baroque painter Giacomo Ceruti (1698-1767), who is not well-known, is a strange amalgam of two usually separate artistic traditions.

The person in a portrait is almost always different from the people in a genre painting, which depicts a scene from everyday life. A portrait painting aims to be specific. A genre painting, on the other hand, is — well, generic. Ceruti, subject of a modest but revealing new exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum — the first of its kind in the United States — is the very rare painter who went for a fusion of the two.

The genre plan is to create a type, a broadly universal representation of humanity doing ordinary things. Whistling while you work, say, or making dinner in the kitchen, celebrating a wedding or playing music or games with friends and associates. The activity might be exact, but the people engaged in it could be anybody — often, just like you.

“Like” is the operative word here. By contrast, “unlike” is the foundation for a portrait.

A great portrait is as precise and unambiguous as possible in representing myriad physical, psychological and social characteristics of someone else — the particular person shown in the picture — and in bringing the unique combination of those attributes to life. A portrait might depict someone admirable or heinous, undistinguished or gallant, and it may be a person who generates feelings of empathy, awe or distrust. But it isn’t you, and that distinction is part of the point.

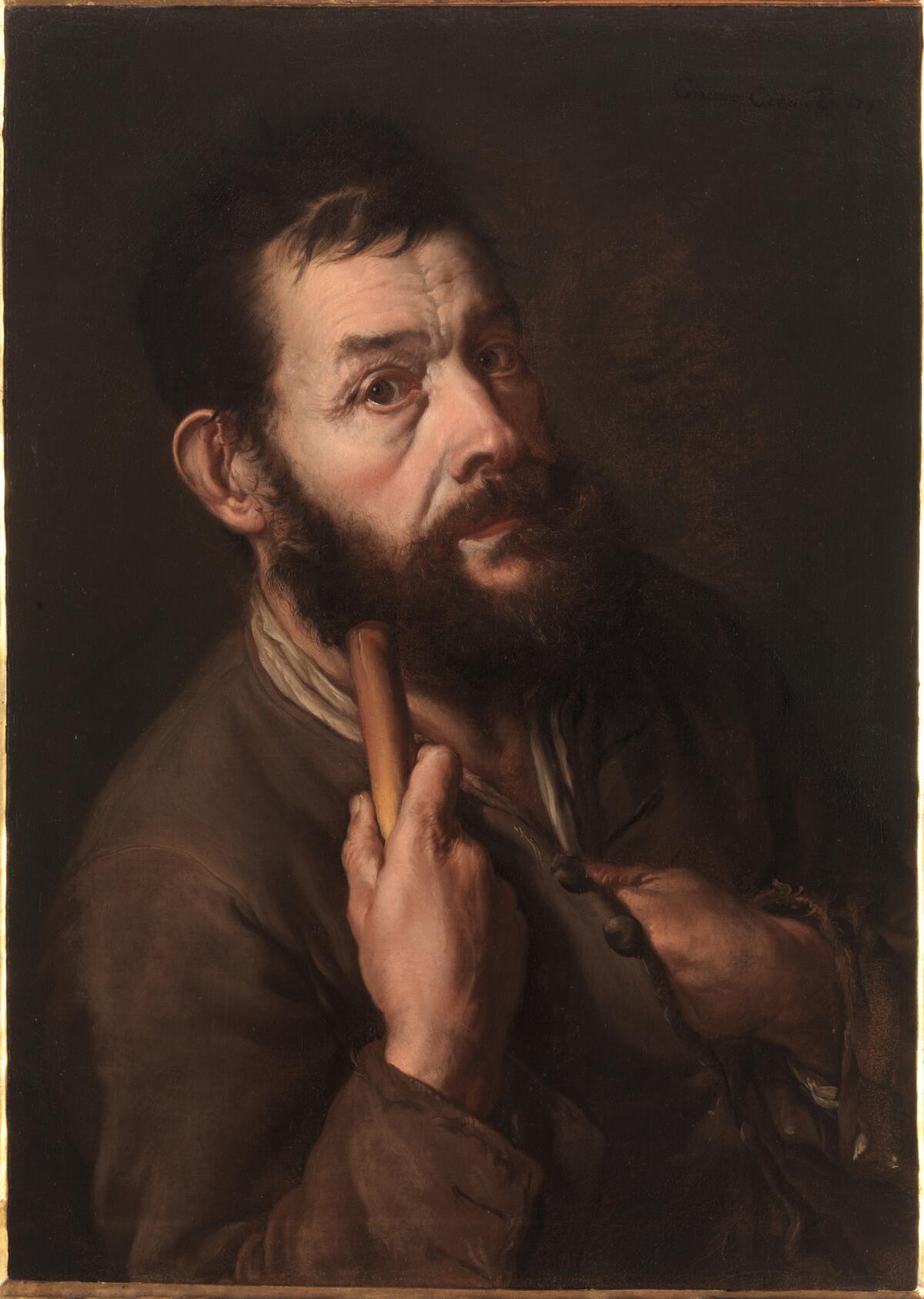

The 17 large pictures in the show, more than half painted when the artist was still in his 20s and all of them completed before he was 40 (he lived to almost 70), generally show life-size men and women sewing, making shoes, playing cards, resting on a religious pilgrimage, tapping wine barrels, spinning wool and snorting tobacco.

Whatever the scene, however, the people are rendered with authority and precision of a kind usually reserved for portraiture.

The result is disarming. Perhaps because we are now so used to seeing photographs that are informal snapshots of people whom we recognize doing ordinary things, suddenly to encounter paintings from the 1720s and 1730s that have an atypical but similar bearing makes them strangely beguiling.

An added distinction: The subjects of Ceruti’s “genre portraits” are utterly impoverished. And they’re very different from the ennobled peasants in popular genre paintings by artists like the Le Nain brothers in France or cheery laborers by Dutch artist Johannes Lingelbach.

A destitute woman draped in a torn and tattered apron mends socks. Slumped on a rock in the woods, an elderly man with a scraggly beard and dressed in patched shirt and pants is a picture of aged exhaustion. Young girls housed in an orphanage are being taught to read or make lace. An apparently penniless street boy in a torn jacket carries a big woven-wicker basket on his back, casting a side-glance in hopes of scoring some work as a porter.

Flinty sufferance emerges. A young girl holds out an alms bowl to beg for help from an equally poor woman engaged in spinning wool. The woman gazes out at us, bereft, as if to acknowledge that she represents the young girl’s future.

Acute naturalism and telling details describe Ceruti’s style. The watchful beggar tenderly holding an alert gray tiger cat in his lap has been bestowed with an attribute of clever endurance. Next to him, a man with glazed eyes and a sloppy grin lays out a rough line of snuff along his wrist, preparing for a swift hit of stress-relieving nicotine.

Ceruti paints all these figures with an intensity of focus, leaving the setting either largely blank — an empty room, a stone wall, the simple suggestion of a forest — or, in five of the 17, a townscape or farmhouse. Quickly sketched in pale hues, the buildings are very nearly a theatrical stage set.

Color is almost always drained from the scene. Its absence makes a point: Pleasure and joy are missing from the lives depicted. Instead, brown, gray, beige and white are dominant, an achromatic palette whose gloomy drabness is only relieved by the surprisingly wide variety of neutrals the artist employs.

Ceruti’s brushwork adds an unexpected note of luxuriousness to “Beggar” (circa 1735-40), a picture of a bearded, gray-haired man adorned in clothing made of a staggeringly complex patchwork. Scores of torn and shredded pieces of cloth are loosely stitched together. The ensemble comes to the edge of what today we would call shabby chic.

The dignity with which Ceruti represents his subjects is underscored in the remarkable pose he chose for this anonymous portrait. With a furrowed brow and earnest eyes looking out directly at a viewer, the beggar leans gently to one side in a posture of subtle deference. He has removed his hat, which he holds out before him in his right hand as if making a request. Ceruti cuts off the hat along the picture’s bottom edge, tamping down the prominence of an appeal.

Look closely, and the beggar’s left hand has disappeared, tucked inside the placket of his tatty jacket. The hand-in-jacket is almost unnoticed amid the bundled panoply of rags. When finally you see it, however, the pose chosen for the portrait startles.

Think of Spain’s Diego Velazquez painting celebrated storyteller Aesop; the American Charles Willson Peale honoring valiant George Washington and Gen. Lafayette; or, France’s Jacques-Louis David elevating Napoleon. The humble vagabond’s pose while asking for alms conjures these and countless other hand-in-jacket portraits of emperors, gentlemen, generals and eminent leaders, especially from the 17th and 18th centuries.

The formal gesture of a hand tucked inside a waistcoat harks back 2,000 years to Classical antiquity. The Greek statesman and orator Aeschines wrote that, in the art of persuasion, speaking with an arm outside one’s tunic is very bad manners. Too aggressive. Pushy even, and not confident. Tuck the hand inside, as Ceruti also did in his own self-portrait as a Catholic pilgrim, painted around the same time.

Ceruti’s use of the gesture confers an aura of dignified understanding usually reserved for the upper classes onto a man who is down and out. Perhaps this indigent fellow was once a soldier — a veteran who had fallen into hard times? We don’t know the answer, but we do know that the wealthy, educated Italian patron for such a picture in 1730s Italy would recognize the subtle pose’s implication.

Ceruti was born in Milan in 1698. He mostly divided his time between his birthplace and Brescia, a pre-Roman city 75 miles east, with sojourns on to Venice. Not much is known about his early life and training, but he made a steady living with commissions for portraits of nobility, historical subjects and church altarpieces — more skilled journeyman than virtuoso. After his death in 1767, his reputation languished, and he was largely forgotten.

His paintings are in museums and churches, but a revival of interest didn’t begin until the late 1920s, when a surprising group of pictures turned up in a rural castle 20 miles south of Brescia. Notably, Italy was then hurtling toward fascist ruin amid economic chaos, with post-World War I poverty on the rise. Twelve of those 13 paintings are at the center of the Getty show, and their distinctive subject matter, size and style of representation has been a puzzlement ever since. Who originally commissioned them, and why?

Getty curator Davide Gasparotto, who organized the exhibition, is careful to note that Ceruti’s paintings are a marked departure from most genre paintings focused on the poor, in that they represent neither comic condescension nor moralizing screed directed at the subjects’ plight. The gravity of social marginalization meets a dignity inherent in the human condition, achieved through portrait-like rendering.

The slim exhibition catalog offers a very good overview of Ceruti’s early career, the paintings’ unusual subject matter and the period’s social perceptions around destitution — a widespread, intractable condition in 18th-century Brescia. Poverty is fundamental to the construction of Christian ideology, and these Baroque-era paintings might be bound up in social and theological concerns around how to approach it in that particular time and place.

In almost every case, at least one man, woman or child looks out from the penurious scene and stares squarely at the viewer, imploringly. A bit of public-service-announcement hangs in the air: “Won’t you help?”

Given the vast wealth gap between likely patrons and these portrait-subjects, the question creates an inescapable aura of noblesse oblige. The paintings are infused with an appeal for the sort of medieval generosity where lords claim an obligation for the well-being of serfs. A look not often encountered in European painting, it’s a self-interested dodge from accepting responsibility for creating — and terminating — the structural conditions that ensure poverty will persist.

Giacomo Ceruti: A Compassionate Eye

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: 10 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Tuesdays–Fridays, 10 a.m.–8 p.m. Sundays-Saturdays. Closed Mondays. Through Oct. 29.

Info: (310) 440-7300, getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.