Inside the growing movement to digitize LGBTQ+ stories: ‘We’re reverse-engineering new memories’ of the past

On Halloween 1969, a group of ink-soaked queer and trans youth covered the office of the San Francisco Examiner in purple handprints.

They were gathered outside the building with picket signs to protest an article using hateful language to describe patrons who frequented nightclubs in San Francisco known as “gay breakfast clubs.”

The writer behind the article reportedly went to the roof of the building and dumped a bag of purple ink on those marching below. Instead of running away, the protesters pressed their purple hands against the building, an act to say, “We’re not going anywhere; you can’t forget about us.”

In response, the Examiner published the names, ages and addresses of LGBTQ+ people involved in these protests to get them fired or evicted.

‘The Stroll,’ premiering Wednesday on HBO and Max, is part of a wave of recent films to reconstruct LGBTQ+ stories from unexpected sources.

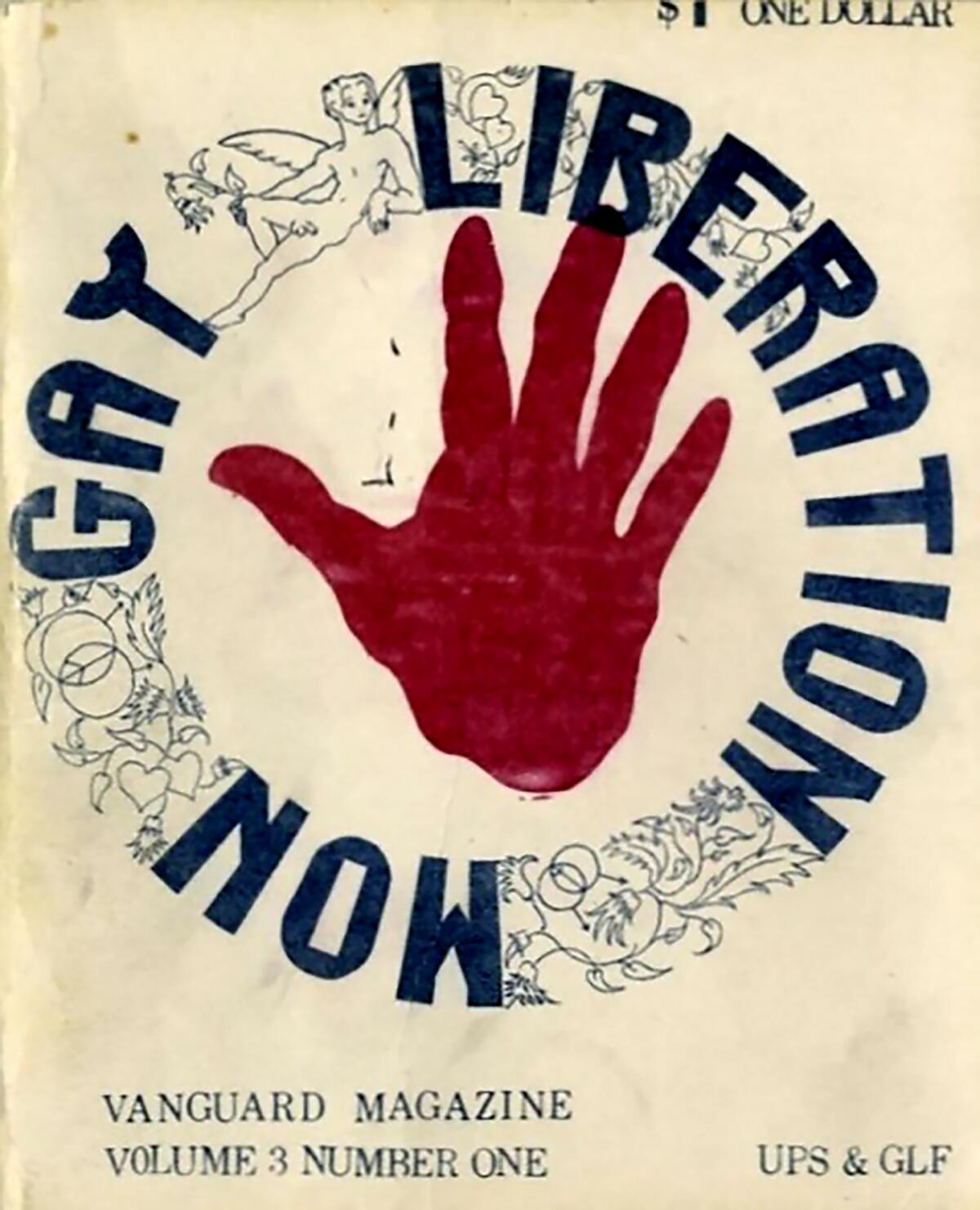

The incident was later referred to as the “Friday of the Purple Hand” and the purple handprint eventually became a symbol of gay liberation for Vanguard, an organization for LGBTQ+ unhoused youth in San Francisco that was active from 1965 to 1967.

“Because queer histories have been actively suppressed by institutions with powers that have historically discriminated and continue to oppress the queer and trans communities, records are really hard to find,” explained Umi Hsu, director of content strategy at ONE Archives in Los Angeles and producer of “Periodically Queer,” a podcast created by ONE Archives Foundation.

“Periodically Queer” launched in 2022 to explore stories of LGBTQ+ history, like “Friday of the Purple Hand,” through audio documentaries. ONE Archives Foundation is the community engagement partner of ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries, the largest LGBTQ+ archive to date. Its work focuses on relating physical archival documents, such as magazines, letters and photos, to today’s world, amid continuous attacks on LGBTQ+ rights and freedom of expression. The goal is to revisit and make accessible LGBTQ+ stories from the past.

“I think of podcast as a digital vernacular of our time. It’s semi-ephemeral and is distributed at scale, but also with the power of audio intimacy, kind of like the oral history medium of today,” Hsu said.

ONE Archives Foundation seeks to engage people with LGBTQ+ history through personal stories to foster empathy and human connection across generations. “Periodically Queer” strives to bring the intimacy and bond associated with physical archives to a digital landscape.

From protests and parades to the homes of early gay rights activists, the Southland has played a key role.

“A lot of digital is adding layers and complexities to objects,” Hsu explained.

Infusing emotion into the stories behind otherwise silent archival documents can be difficult. In Season 2, the “Periodically Queer” team often incorporated a second-person point of view to immerse the listener in the world of 1960s San Francisco through sensory details, including describing the thick texture of the paper and the hand-painted cover art on Vanguard magazine, all made accessible without visiting the physical archive.

“Imagine this. You’re in the basement of a church. You see a sign that says, ‘Dance in the dining room.’ You walk in, the dining room is cavernous, chairs stacked against the walls. The ceiling light is off. A blue spotlight shines on the floor. Lit cigarettes twinkle in the dark. Behind a pile of records and a turntable is a DJ. Warm air on your face. It’s the summer of 1966,” begins the first episode of Season 2, a description of a Vanguard summer dance updated to include gender-affirming language.

The LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory, the largest LGBTQ+ oral history project in North America, takes a similar approach, collaborating with the ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives and the Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria to bring LGBTQ+ stories to digital spaces. They are currently working on an oral history project for the Pussy Palace — later renamed the Pleasure Palace — a queer bathhouse in Toronto raided by police in 2000. The project uses Instagram stories, live-action and animated shorts, interviews and “sensory portraits,” in which attendees described the atmosphere of the Palace, to transport listeners to the scene.

With approximately 1% to 2% of ONE Archives fully digitized, Hsu says “Periodically Queer” aims to create a dynamic relationship between history and the present, combining sound bites with descriptions using inclusive language to reflect the diversity of underground LGBTQ+ collectives.

The first season of “Periodically Queer” catalogs the history of LGBTQ+ magazines from the 1980s to early 2000s, including Lavender Godzilla — published by the Gay Asian Pacific Alliance — and COLORLife!, the Lesbian, Gay, Twospirit and Bisexual People of Color Magazine, which ran from 1992 to 1994 in New York City.

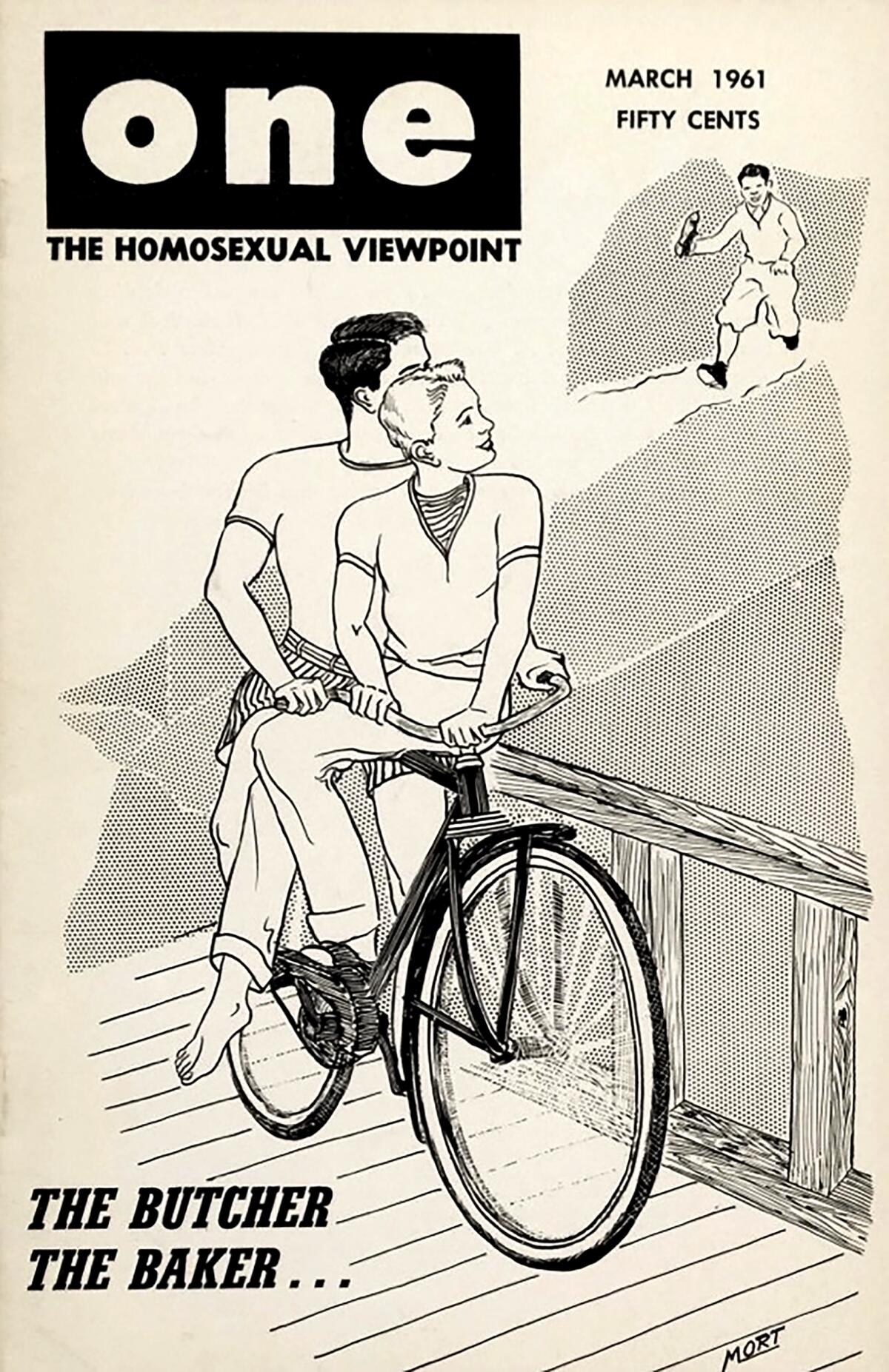

Season 2 of the podcast, released last month, explores the history of the unhoused queer and trans youth behind Vanguard magazine and ONE Magazine, the first publicly distributed LGBTQ+ magazine in the United States. Its two episodes create immersive auditory spaces that resurrect events in LGBTQ+ history that remain largely unexplored.

Making Gay History (MGH) is a nonprofit similar to ONE, with a podcast dedicated to reinstilling LGBTQ+ voices within a larger, communal history. Over the span of 12 seasons, “MGH” has used rare interviews with LGBTQ+ figures to explore queer and trans history, ranging from the historic Stonewall rebellion to profiles of lesser-known activists like Jean O’Leary, featuring archival audio weaved through explanations of what was going on at the time, providing context for that moment.

Season 2 of “Periodically Queer” features a similar combination of sound bites, interviews and personal testimonies, but Hsu said finding audio wasn’t always easy. Records of trans youth and adults were particularly difficult to track down; the majority of their information came from police records and news stories, both of which usually involved descriptions of people “cross dressing.” As a result, firsthand accounts of the experiences of queer and trans individuals, especially youth, often went undocumented.

Physical documents have wrinkles, folds and creases — all signs of human touch. Sound animates those textures, bringing them to life through audio. Hsu considers sound to be a relational technology, creating an intimate space for marginalized voices to tell their own stories.

“In a way, I feel like we’re reverse-engineering new memories of a past that counter the mainstream narrative that queer and gender-nonconforming people don’t exist in history,” they explained.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.