Review: An unforgettable performance by SF Symphony reveals Busoni in his full glory

San Francisco — Being called by some a failed city, San Francisco struggles to recover from the pandemic. The view from the street is all too often that of an appalling income divide in which the Silicon rich who remain (or return enticed by an AI gold rush) wage war on the unhoused.

Even so, San Francisco retains its hard-won pride and its glory. And both were on display June 25. It was the day of the Pride parade, and no other city does Pride with San Francisco’s civic flair and affection. Civic Center, an area San Franciscans often avoid, was full of festivity. Across the street at Davies Symphony Hall, the San Francisco Symphony offered a glory-bound piano concerto unlike any other.

Busoni’s flabbergasting Piano Concerto, led by Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen and serving as a showcase for Igor Levit as a superhuman soloist, was the full program. The concerto was written between 1902 and 1904. It lasts 75 minutes. The piano part challenges the notion of what is humanly possible on the keyboard.

In their ceaseless attempt at seducing us with music at once exotic and accessible, the recording companies continue to affect live-performance repertory.

In it, Busoni looks back to the 19th century for inspiration and ahead to the modernist promise of the 20th. His aural gaze further reaches beyond Europe to the East and the far West, and the composer finds everywhere prospects of universal substance and spirituality.

There are hymns of blissful beauty. There are ecstasy-driven Italian dances, their staggering wildness unfettered. There is a final fifth movement that employs a hidden male choir singing an extravagant ode of mystical awe and jubilation to Allah. It goes without saying that Busoni’s concerto conspicuously goes where none had before, and none have dared since.

The score is not unplayable, it just seems that way. It has long been a cult favorite, several times recorded, but very rarely heard in the concert hall. This was its belated San Francisco premiere and Salonen’s and Levit’s first go at it. Levit’s fingers flew so fast through absurdly complicated passages that it was hard to believe one’s own eyes and ears. Viewed on video, such playing might appear fishy.

But in the flesh, the communal exultation of Levit, Salonen, the orchestra and chorus captured something so large and impractically visionary, something that had so much to say about the society to which we aspire, that one could walk out of the concert hall convinced we can make a difference.

The Bay Area is celebrating — to say nothing of capitalizing on — the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love.

Can we kid ourselves that an outsize piano concerto written by an Italian composer who died a century ago in Berlin might save an American city? Maybe not, but the massiveness of Busoni’s expectation matters in ways both immediate and forgotten. As composer, virtuoso pianist, theorist, highly opinionated futurist and pedagogue, Busoni exerted a little-acknowledged, though crucial, component of the cultural identity of San Francisco and beyond, Los Angeles very much included.

He imagined highly originally new music, and he sent his protégés out into the world, full of radical ideas. His two most important wound up in California. The stellar Dutch German pianist Egon Petri landed at Mills College in Oakland in 1947. Busoni’s favorite pupil, the lesser-known and far stranger American pianist Richard Buhlig, settled in Los Angeles in the 1920s.

Together, if independently, Petri and Buhlig became hidden progenitors of West Coast music, which means everything from the forces in the beginnings of the world music movement, the birth of minimalism, the advancement of microtonal music, the 1950s avant-garde and the electronic music of the 1960s.

The Mills that Busoni arrived at was a musical melting pot, and a place ripe for Busoni’s ideas about the future of music, which included a radical rethinking of harmony (including, as early as 1906, proposing dividing the octave into 36 intervals). The school had become an idyllic and idealistic refuge for inventive French composer Darius Milhaud and the Budapest String Quartet, escaping the Nazis. Petri fit right in as a proponent of Busoni’s prophetic vision, and as one of the world’s most celebrated pianists, he was particularly well poised to influence a generation of outstanding students.

Petri, of course, promoted Busoni’s music, including the Piano Concerto, in which he was a noted soloist for many of its early performances. One of his Mills students, Daniell Revenaugh, became the mastermind and conductor of the concerto’s first commercial recording in 1967 (featuring another Petri student, John Ogdon, as soloist) that set off a modern rediscovery of Busoni.

But during his decade at Mills, Petri was just as adamant about propagating Busoni’s ideas about transcription, time and reinvention of early music (particularly in imaginative piano transcriptions of Bach). Busoni’s interest in microtones and invention in new instruments helped legitimize Harry Partch, who began putting on staged events at Mills in the early 1950s. All of this helped set the stage for Mills housing the most progressive music department in the country. Such now legendary mavericks as Morton Subotnick and Pauline Oliveros got their professional starts there. Steve Reich studied at Mills.

Ten years after Petri’s death in Berkeley, Terry Riley joined the faculty in 1972, the same year I began graduate studies in the music department. It may surprise Riley to learn this, but he was hired, the head of the department told me, because she felt he had the imagination and skill to carry the Petri tradition into a new age.

A fellow student, Rae Imamura, who became a prominent pianist in the East Bay new music scene, had studied with a Petri student when she was young. Her father was the head of Berkeley’s Buddhist temple, where the Beat poets loved to hang out in the 1950s and 1960s. Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso and the gang doted on the little girl who played Bach for them. But, as Rae liked to say, she played Busoni’s Bach arrangements. They sounded hipper to the poets. In this and many other ways, Busoni became part of the San Francisco zeitgeist, beats and hippies very much included.

Buhlig, who was born in Chicago, studied with Busoni in Berlin and taught in New York before moving to L.A., had an even bigger influence. He was one of Schoenberg’s favorite pianists. He helped found Evenings on the Roof, which became today’s Monday Evening Concerts. He mentored Henry Cowell, California’s first great composer, whom Buhlig took to Berlin to meet Busoni and who went on to instigate the world music movement. Buhlig was John Cage’s first composition teacher, sending the naive young composer on his music-changing path. Busoni was always somewhere in the background.

For that matter, the New York School of the 1950s around Cage was also Busoni-shaped. It included composer Christian Wolff (who studied with a Buhlig pupil) as well as pianist David Tudor and composer Morton Feldman (both of whom studied with composer Stefan Wolpe, a Busoni pupil). Through Cowell and Cage, Busoni’s prophecies found their way into the New School of Social Research, where Cage’s classes led to the founding of the Fluxus movement that reached, be it second- or third-hand, the likes of, say, Yoko Ono.

Back to L.A., a close friend of Buhlig was Sol Babitz, one of Stravinsky’s favorite violinists and prominent in both the pioneering new music and early music scenes. Babitz’s daughter Eve, the writer who captivatingly chronicled her L.A., grew up to sounds of her father and Buhlig playing Busoni.

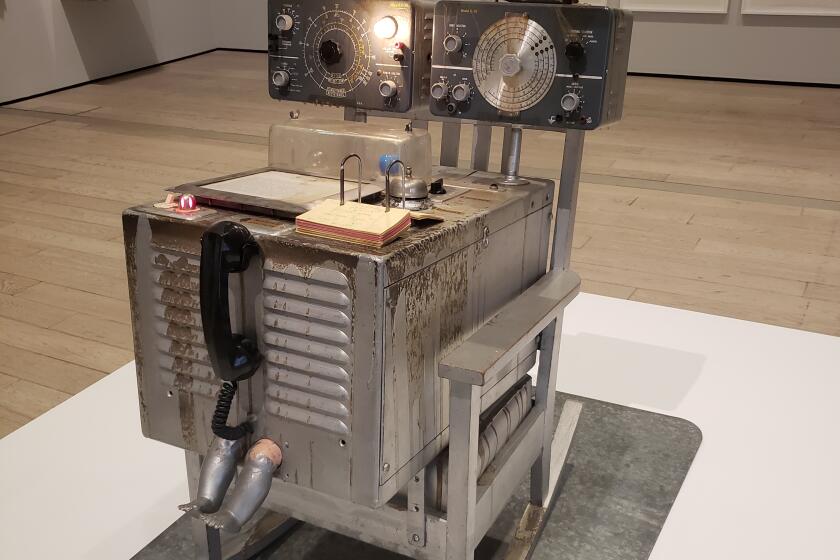

He may lie deep in the background, but you cannot escape Busoni. Featured in “Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982,” the illuminating recent Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition, is Cage’s “HPSCHD,” from 1969. It involved processing on a then supercomputer seven pieces for harpsichord, one of them by Busoni.

A new LACMA show takes on art in the computer age, the Tony Award nominations, and an influential artist L.A. collective grapples with copyright disputes in this week’s newsletter.

So, yes, the San Francisco Symphony has reason to take great pride in reviving Busoni’s most extravagant score. But that still leaves the question about the state of San Francisco. Rather than a vision of greatness rooted in a special city’s zeitgeist, a Herculean performance, for all its glory, felt almost like a fleeting vision. The orchestra has no plans to include it in its weekly radio broadcasts or to release a recording.

In a prophetic letter written on a concert tour of the U.S. in 1893, Busoni warned that in America, “the average is better than elsewhere, but along with that there is much more average than elsewhere, and as far as I can see, it will soon be all average.” Call San Francisco what you will. But average?

The city has its problems. They are not unique. But it also had Busoni as a subliminal cultural influence and the San Francisco Symphony on Pride Sunday, standing for glory. Retaining that sense of glory and attending the example of overcoming the concerto’s colossal obstacles promises a more equitable future for this idiosyncratic city — and the rest of us — rather than its tech profiteers reducing all to the law of averages.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.