A new L.A. residency for AAPI dancers aims to dismantle what ‘choreography looks like’

On a recent afternoon at the dance studio Stomping Ground L.A, choreographers in Blue13 Dance Company’s Playdate residency split up into duos for one-on-one speed dating-like chats. The four “playdaters” would spend time talking with one another about their careers, movement styles and aspirations for the residency.

Ramita Ravi, whose style is infused with jazz and contemporary influences, combined forces with Jainil Mehta, who draws from ballet traditions and Indian classical. Jiayin “Tokie” Wang, a recent graduate of the California Institute of the Arts whose work is more contemporary and multimedia by utilizing video and visual arts, paired with Barkha Patel, a Kathak dancer and choreographer.

After testing the waters with their collaborators, the four came together as a group to work on a new piece. The result was an unexpected, unifying experience for the first cohort of Playdate. While the selected artists each have their own unique styles, the residency offered room for growth in each pairing as they challenged themselves to create, learn and, more important, play.

Blue13 Dance Company artistic director Achinta S. McDaniel created Playdate because she always felt “uncomfortable” in the field of dance and choreography because she was often the only Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander dance artist in the room. She felt she often had to explain her work. Her experience in the industry led McDaniel to create the two-week residency.

“When I was in a space with this cohort, we were nodding, we were accepting,” McDaniel said. “We understood each other. There was a vocabulary. There was a movement dialect in common. There’s a verbal dialect in common that we don’t have to explain, and it’s just so comforting.”

After the first day of the residency on June 12, she told her husband, “I felt so at ease.”

“It’s so rare to feel that,” she added.

McDaniel was disheartened to realize that experiences like this are still so few and far between, even after all the time she’s worked as a choreographer for over 20 years. But as Playdate came to life, she felt excited for the future.

Playdate was a decade in the making, McDaniel said. Its first iteration was done virtually 2021 as a presentation at the Assn. of Performing Arts Professionals conference based in New York. This time around, the residency took place in person, with the support of a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Unlike with most residency programs, McDaniel wanted to do more than just offer a place to create. She wanted to make the residency process more collaborative (unlike most that only offer space and money), partnering with local organizations such as the Music Center. Prospective choreographers applied for the residency online, submitting a questionnaire and work samples. McDaniel then selected the final four.

Ravi recalled having conversations with the other resident artists about “dismantling what dance and choreography looks like.” McDaniel brought in representatives from L.A.-based organizations such as Satrang — a South Asian LGBTQ+ organization — and Infinite Flow Dance — a company made up of dancers with and without disabilities.

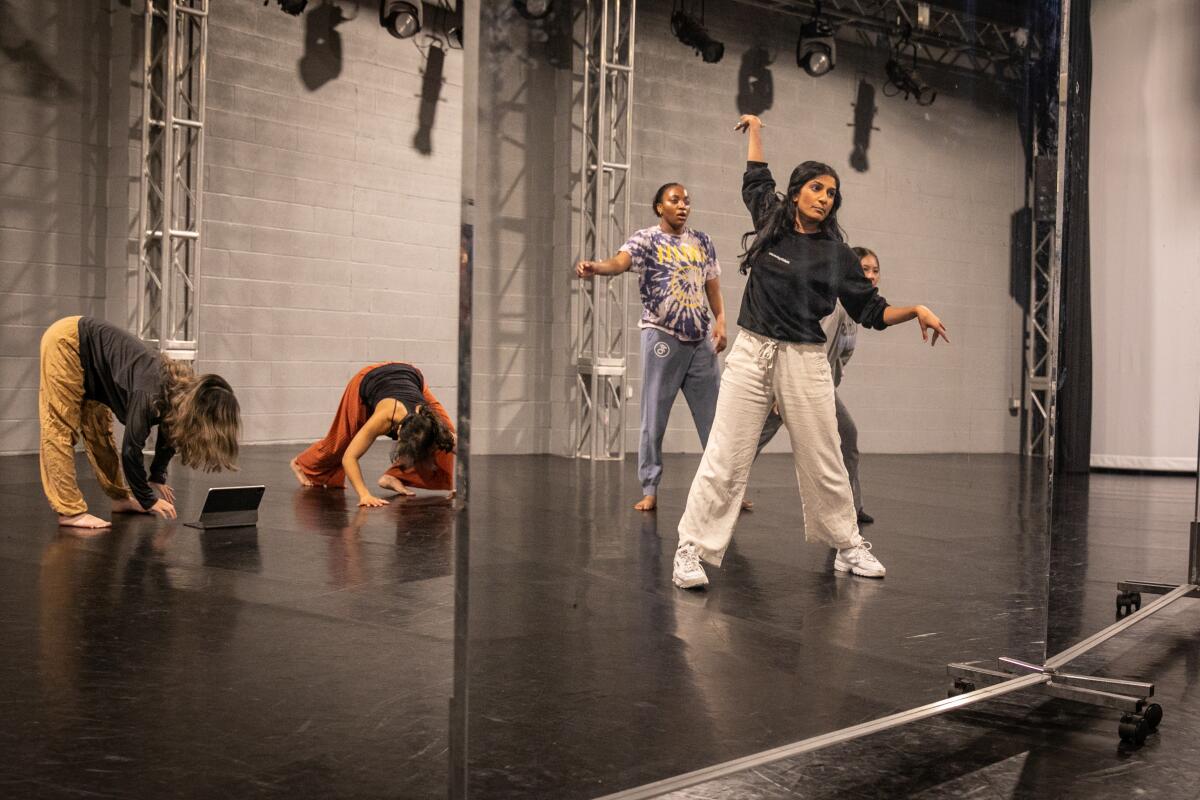

This month, for instance, the Playdate artists were deep into their work at their rehearsal space. On one side of the rehearsal room, Ravi and Mehta choreographed a murder mystery piece titled “A Night to Rewind.”

The story immerses audiences into a party scene. During Playdate’s end-of-residency showcase June 23, the duo (alongside fellow dancers in the piece), encouraged members of the audience to step onstage and dance along. Suddenly, one of the cast partygoers dropped dead. Events leading up to the “murder” were danced onstage, showing how everyone at the party had a motive. But it was up to viewers to decide whodunit.

The idea was unexpected for Mehta and Ravi. Mehta initially planned to work on a contemporary ballet for the residency, but that changed as the two started sharing ideas for something more narrative. “We’re bringing a lot of our personal influences, but it has nothing to do with our culture or identity,” Ravi said. “I think that it’s pretty unexpected in that way, because people try to box you in.”

On the other side of the room Wang and Patel took a slower approach, focusing on choreographic details that embodied similarities between cultural deities in Buddhism and Hinduism. Patel taught the choreography to one of the dancers in their piece, pointing out a flexed foot and the shifting of weight from one side of the hip to the other, which gave shape to their goddess character in the piece.

Before Playdate, Patel worked on a piece at the 92nd Street Y in New York that included the story of Kali, a goddess of change and destruction in Hinduism. Wang connected Kali to Guan Yin (Avalokiteśvara), a thousand-armed figure in Buddhism that upholds compassion.

“Their mission is the same — generosity — but the pathway that each of these entities takes is different,” Patel said. “Kali is very fierce, and Guan Yin is very compassionate and soft.”

Wang saw the collaboration as a “fun fusion of culture,” evocative of the exchange of ideas and cultural backgrounds throughout the residency.

“We’re blending very intentionally Kathak, Chinese folk and contemporary dance,” Patel said. For Patel and Wang, it felt as if they’d created a whole new style. Their piece, “KhaYin,” brought the duo and their dancers together to create one flowing organism onstage.

After sharing the final piece during the showcase, Patel admitted that she came into the residency hoping to be paired with a contemporary dancer. She said she grew so much from her collaboration with Wang, breaking away from the typical rhythmic music she works with to electronic music by Jlin.

These discussions of styles and cultural influences are not often seen in the dance world, especially concert dance.

Over her career, McDaniel has seen a subtle shift in representation, with popular TV shows like Netflix’s “Never Have I Ever” highlighting South Asian talent. However, she says seldom has there been attention given to AAPI representation on the dance stage.

“We constantly have to educate,” McDaniel said.

Blue13 and Playdate focused on making audiences rethink what AAPI art looks like. For Ravi, that meant rejecting the myth that there can be only one AAPI dancer in the room. “I’ve been the only one in a space for a lot of my career,” she said. “I don’t always have to carry the weight of representation on my shoulders.”

While Patel’s work focuses on Kathak, she recalled consistently being asked to teach Bollywood classes — a completely different style.

“When people are not aware or haven’t done the work [to understand], they’re always [saying things] like ‘Tell us about the form’ and ‘Tell us what Kathak means’ versus ‘Hey, let’s talk about the content of the work you’re creating,’” Patel said.

These examples resonated with the residency’s participants and McDaniel. She says that throughout her career, she’s faced microaggressions that forced her to educate people on her work and culture.

“There’s no explanation at times, and there’s already a feeling of camaraderie,” Patel said. “I don’t feel like I need to explain to this person what it is that I do.”

McDaniel hopes to expand the residency by adding more participants, different cities and exploring even more intersectional identities within the AAPI community.

After the presentation at Stomping Ground L.A., McDaniel said she hopes the collaborations and pieces live beyond the residency. Playdate became a space that is rare in dance, one that allowed dancers of differing cultures and backgrounds to exist unapologetically.

“When you’re not getting the things you want, especially in a place like America, there is space to build it,” Patel says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.