Do touch the art. This first-of-its kind L.A. artwork offers a tactile cityscape

You could say that Megan Whitmarsh and Carla Tome are particularly hands-on regarding their new public art project, which debuts April 26.

The artists, who are not blind, created a large sensory wall and companion mural at the Braille Institute Los Angeles. The commission is part of a three-year, $2-million renovation that the East Hollywood nonprofit is unveiling this week. The 104-year-old institution now has a state-of-the-art recording studio to create audiobooks for patrons, as well as a new teaching hub with iPads, laptops and Braille e-readers that offers workshops for using those and other devices.

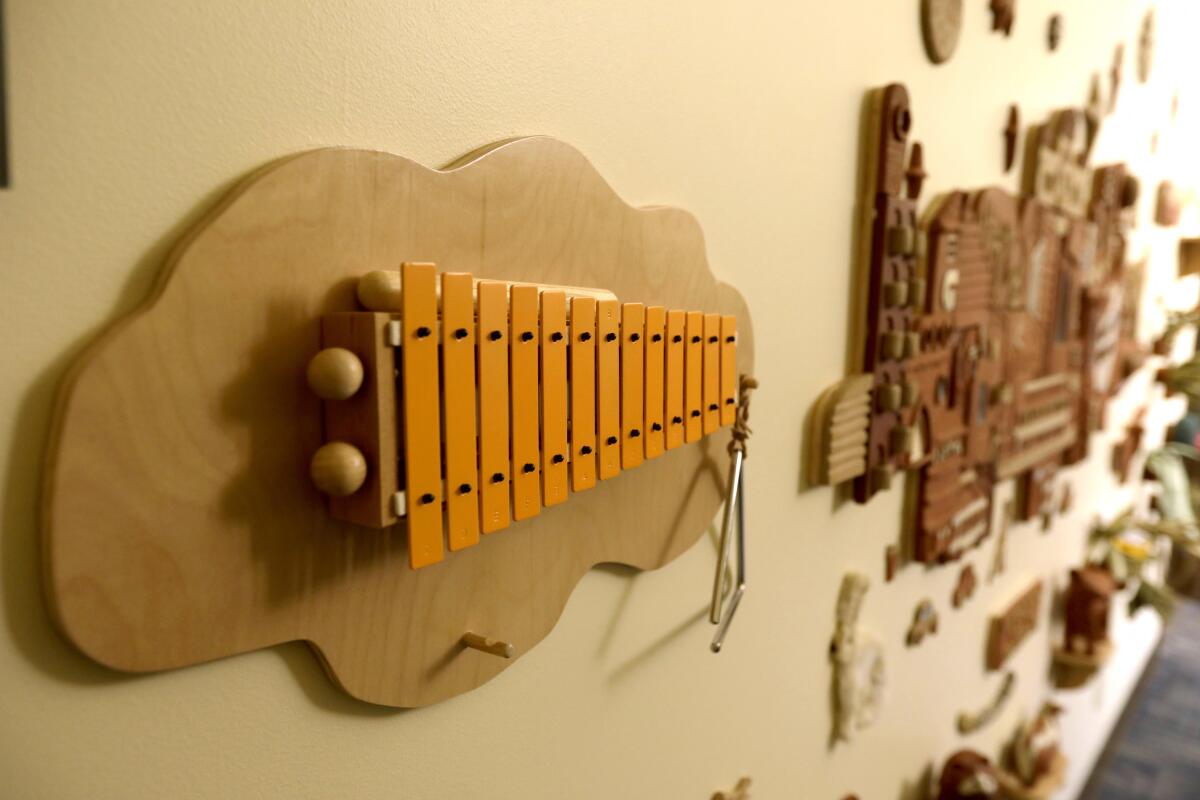

The sensory wall — in the children’s room at the Braille Institute’s library — is the first of its kind in Los Angeles, a handmade, public artwork incorporating ceramics, textiles, musical instruments and prerecorded audio telling a story about Los Angeles that visitors are meant to interpret with their hands.

The wall traverses a cross-section of local terrain, including desert, mountain and ocean, and it depicts native plants, animals and local landmarks. There’s a faux fur bunny, a ceramic coyote and raccoon. There are hanging succulents crafted from velvet, beads, cotton and gauze with satiny fringe. The Griffith Observatory and Capitol Records building are present along with a nearby Vermont Avenue bus station and faraway stars and the moon. There’s even a flying spaceship to “welcome everybody,” Whitmarsh jokes.

“It’s called ‘Many Hands Many Roads,’” Whitmarsh says of the piece, “because it’s the many roads out of Los Angeles and the many roads of Los Angeles. And everyone’s individual path.”

The sensory wall is particularly interactive.

At one end there’s a small, protruding cave made from clay and textiles. Inside are ceramic forms that look like bone fossils. They’re impressions that staff and patrons made by squeezing clay between their hands. Children can reach into the cave and touch the tubular objects, resting their fingers in the indentations, which feel cool and smooth and curiously reassuring.

“It’s like holding someone’s hand,” Tome says.

Small, hollow wooden eggs filled with seeds inside the cave are just one of many musical elements. There’s a hanging triangle, a xylophone and wind chimes. Visitors will have access to a nearby recording studio and their audio pieces will play on a smartphone-activated speaker above the sensory wall.

“It’s a living part of the piece,” Whitmarsh says, pulling tiny felt bunnies out of a miniature ceramic apartment building on the wall. The youth program and child development program [here] can work with the children to make sound pieces — they can make animal sounds, create stories about these bunnies. They can make their own podcasts and have them play in here.”

The sensory wall, like the Braille Institute’s library itself — part of the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, Library of Congress — services the blind, visually impaired and print disabled, the last meaning those who can’t read standard print mediums. So Whitmarsh and Tome also created a colorful companion mural in the lobby. It’s a painted cityscape of L.A. that functions as a sort of diagram or illustrated map to the sensory wall, loosely mirroring it for those with some degree of sight. It features bright colors, bold shapes and scattered ceramic elements, such as a car or a fish, labeled in Braille. A large ceramic arrow directs visitors around the corner to the sensory wall.

The two works are a celebration of the city, Whitmarsh says. “Because L.A. just has so many layers and every kind of culture and idea and diversity all put together.”

Whitmarsh and Tome are Highland Park neighbors and have been close friends for more than 20 years. This is their first collaboration and the process felt especially natural, Tome says, with each artist lending a complementary expertise.

“We both have our own styles, but we work so great together,” Tome says. “The entire wall is both of us equally.”

Tome studied at the San Francisco Art Institute and is primarily a ceramicist as well as a painter, illustrator and woodworker. She’s exhibited at L.A.’s Craft Contemporary and has taught art there as well as at East Los Angeles College and other locations.

Whitmarsh is a multidisciplinary artist who trained in painting and sculpture and is known for her textile work. She studied at Kansas City Art Institute and the University of New Orleans and has shown her work in galleries and museums internationally, including the Hammer Museum’s 2018 “Made in L.A.” biennial.

Braille Institute Director of Library Services Lisa Lepore was connected to the artists through the library director at LACMA, Alexis Curry. The institute’s committee chose Whitmarsh and Tome for the commission because “right away, we just loved their energy, their curiosity, their work ethic and what they wanted to bring to this project,” Lepore says.

Lepore plans to work with a blind artist in the future, and the institute is planing an art gallery for the blind and visually impaired, featuring artists and guest curators. “And we’re going to work with our art instructors and students to riff off the sensory wall — to teach from it, have classes and make art from it,” she says.

Whitmarsh and Tome took inspiration from the textured aesthetic of Ruth Asawa’s 1970s bronze sculpture and fountain outside the Grand Hyatt San Francisco, as well as Judy Baca’s “History of Highland Park” mural, painted with L.A. artists Joe Bravo, Sonya Fe and Arnold Ramirez, on the neighborhood’s AT&T building.

Because the sensory wall is intended for children to touch, Whitmarsh and Tome spent extra care sanding the ceramics after every firing, so there would be no sharp edges. At the same time, they added elements for partially sighted visitors, such as a globe that glows in different colors.

“The challenge for us was to make it attractive, because some people are partially sighted,” Whitmarsh says, “and also diverse in its tactility.”

“And to make it art,” Tome adds. “If you engage your audience you can raise the level of their expectations. We hope that this stimulates their creativity so maybe they want to make art.”

The Braille Institute will unveil its new library at a free open house Wednesday from 10 a.m.-2 p.m. Whitmarsh and Tome will be on hand to introduce visitors to the sensory wall.

“I think there’s this misconception,” Lepore says, “that if someone can’t see, the aesthetics don’t matter. And that couldn’t be further from the truth.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.