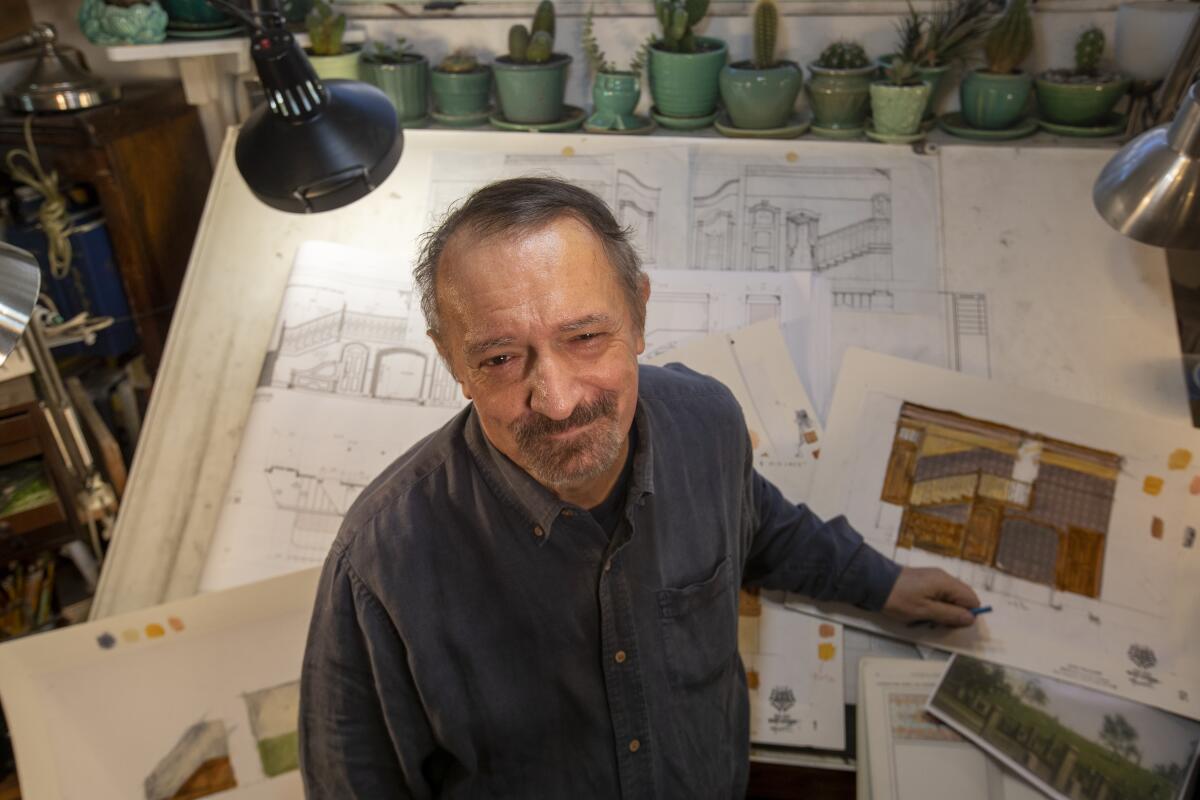

John Iacovelli, beloved L.A. theater set designer, dies at 64

John Iacovelli, the Emmy-winning prolific scenic designer for stage and screen, whose ability to balance poetics with pragmatism made him a beloved and invaluable collaborator for Los Angeles theater artists for many decades, died Friday after a long battle with cancer, his family told The Times. He was 64.

His range was limitless, moving effortlessly on stage from lavish musical spectacle to Beckettian minimalism, on screen from the space opera of “Babylon 5” to the instantly recognizable reality of “Lincoln Heights.” Theater was his true love and the dream factory Iacovelli operated seemed to run around the clock, but precision was never sacrificed by speed of production.

“John worked scenic miracles on Los Angeles stages throughout his long and distinguished career,” said Times theater critic Charles McNulty. “His fertile imagination and practical know-how could endow any work from the repertoire with just the right amount of whimsy, lyricism and realism.”

“His death represents an incalculable loss for L.A.’s theater community,” McNulty added. “He was a pillar of the scene here, a beloved and trusted counselor to fellow artists, an amiably enlightening interlocutor with critics and an impish presence who embodied theater’s Dionysian spirit.”

Iacovelli worked with budgets big, medium and small, conjuring from the resources at hand the scenic magic required to transport an audience to the aesthetic world of the play or musical. But he was, first and foremost, a practical man of the theater.

As he told The Times’ Mary McNamara in 2020, “In the end, the set is there to serve the actors. … It is a machine for action.”

It took six months, and 40 years experience, for production designer John Iacovelli to create the set for “Arsenic and Old Lace,” even as he fought a battle of his own.

In a career spanning more than 40 years, Iacovelli designed sets for at least 300 stage productions: for national tours, internationally, on Broadway, for large regional theaters and every cramped, dusty 99-seat house in and around L.A. He moved seamlessly between the stage and Hollywood, working on films including “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids” and “Ruby in Paradise,” and TV series including “Babylon 5,” “Resurrection Blvd.” and “Ed.” He earned an Emmy for the stage production of “Peter Pan” he had designed, which played on A&E.

Awards didn’t slow him down a bit: Even after winning the 2018 United States Institute of Theatre Technology‘s distinguished achievement award in scene design & technology, he continued working on a seemingly impossible number of projects simultaneously — up to 18 shows a year. “People think I say yes to everything,” he said in a recent podcast. “They don’t know about the shows I turn down.”

All the while he was teaching full time at UC Davis, where he had developed the design curriculum of the MFA program. “All of my kids are working,” he said of his many students there over the years.

“John was the most generous theater practitioner I ever knew. And I’ve known him for 40 years,” said director Eli Simon, chancellor’s professor of drama at UC Irvine. “He was in a constant state of creativity and sharing. We were at a show and there were a couple of young scenic designers at the show. [At intermission] he came up to them and said, ‘OK, after the show, I want you to tell me five things that worked about the scenic design and five things that didn’t. I know what they are, but I’m not going to tell you right now.’ That was John in a nutshell. He was humble and generous and a teacher at heart.”

He retired from teaching in 2019. A diagnosis of lymphoma wasn’t part of his plans, but even that failed to slow him down; he worked without breaking stride throughout his treatment and into his remission. When he learned this year that his cancer had returned, he was deep in the design process for La Mirada Theatre’s “Did You See What Walter Paisley Did Today?”

But if Iacovelli was the platonic ideal of designers in many ways, it must be said that his sets didn’t politely fade into the woodwork: They stood out as exemplars of the form even in the L.A. theater community, which boasts many brilliant set designers (all Iacovelli’s friends).

Playwright Justin Tanner recalled the way Iacovelli’s work transformed a space: “He managed a level of realism that made you forget,” Tanner said, noting he first worked with Iacovelli in 2018 on his play “El Niño” at Rogue Machine. “If you didn’t look at the audience, you felt like you were in a real environment ... just the detailing and his artistic eye ... it was a combination of fabulous and naturalist.”

Critics took note of the majesty of his set for the 2012 play “The Heiress” at the Pasadena Playhouse. Iacovelli had visited the preserved mansions of New York’s Washington Square Park for inspiration, and many had trouble imagining that any of them could be as beautiful as what he created. Particularly the serene, ethereal blue of the walls, which served as a particularly effective backdrop for the brutal emotional experience that followed.

Sheldon Epps, the former artistic director of the Pasadena Playhouse, who first worked with Iacovelli in 1999 on “The Importance of Being Earnest,” remembered Iacovelli as singular in a profession known for individuality.

“I know few people who’ve worked in the theater as long as John did who remained passionate about the art form. So constantly joyous about the act of creating — both his own work and celebrating other people’s work,” Epps said.

Theater enthusiasts recalled delighting in spotting Iacovelli’s work in theaters large and small all over Los Angeles: the way two unremarkable walls in DOMA Theatre’s revival of “Young Frankenstein” opened up to reveal a gloriously ornate mad-scientist laboratory. A foreshortened dining room visible through a glass door at Antaeus Theatre Company’s production of “The Little Foxes” looked like a purely visual component until somehow, late in the play, the entire cast went in and sat around the table.

There was never a gimmick or “tell” that screamed “Iacovelli.” What tipped people off was an authenticity in the details, some ineffable harmony between the actors and their milieu. Iacovelli’s living spaces always looked livable. “You could move in,” his close friend, actor Alan Mandell, said of his set for “Dance of Death.”

“There are any number of people who owe him a debt of gratitude for the scenic work he did,” Mandell said. “He spoke his mind, clearly and forcefully about the work that he was doing and what he felt you should be doing right or wrong. In a field where disappointment is rampant, he was able to convey his appreciation for your attempt to do something significant. I shall miss him terribly.”

Production designer and art director John Iacovelli has worked on sets for TV spectaculars (“Peter Pan”) and series (“Ed,” “Babylon 5”), feature films (“Honey, I Shrunk the Kids”) and scores of stage plays, but the Emmy winner’s most theatrical — and personal — interiors can be found in his 1927 Atwater Village home, which is filled with furnishings and memorabilia from his decades-long career.

Iacovelli often said he didn’t consider himself an artist. His father, he maintained, was the “real” artist in the family. His father and mother, a government worker, settled in Reno. When Iacovelli was 7 or 8, his father built him a puppet theater, to which he often attributed his enduring fascination with scenic design. Iacovelli spent his childhood forming theater troupes with friends; when it was time for college, he applied for and earned a scholarship in scenic design at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. There, he recalled, he was taught that film and TV were “a nasty business.” But when he entered the master’s program at New York University (renamed the Tisch School of the Arts), he was startled and then excited by its all-embracing attitude toward the screen as well as the stage.

Classmate-turned-production-designer Larry Fulton (“The Sixth Sense,” “Unbreakable”) persuaded Iacovelli to leave New York for L.A., where his career quickly caught fire and he never looked back.

Throughout his life, Iacovelli remained devoted to learning as much as he could about his chosen art form.

“I never knew him to travel anywhere without coming [back] with a new load of books,” Epps said. “To the point where he actually had to extend his home so he could store his art collection and all of his theatrical memorabilia. Going to his house was like going to a theatrical library.”

Iacovelli is survived by sisters Violet Iacovelli, Angaela Iacovelli, Victoria Williams and Dariel Wines; brother Cameron Iacovelli; nephews Ian Van Rensselaer, Skylar Van Rensselaer, David Iacovelli and Spencer Williams; and nieces Melanie Lewis, Sylvia Micheli and Rochelle Iacovelli.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.