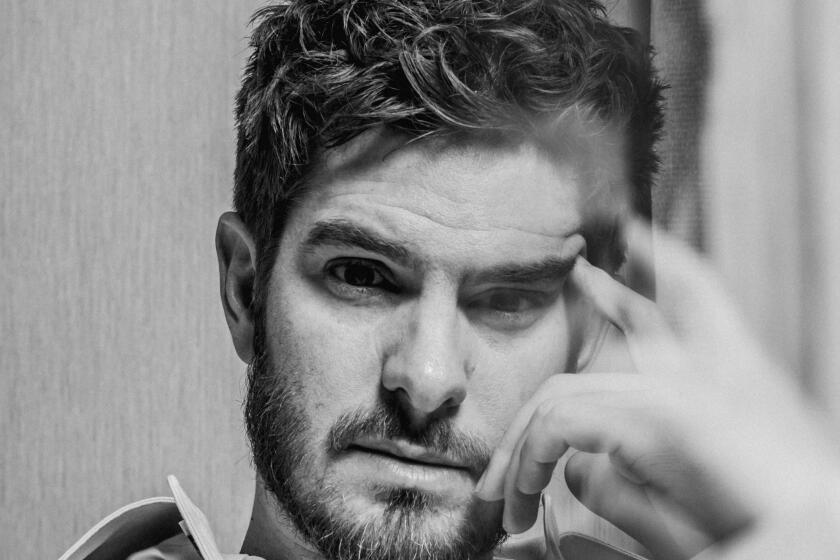

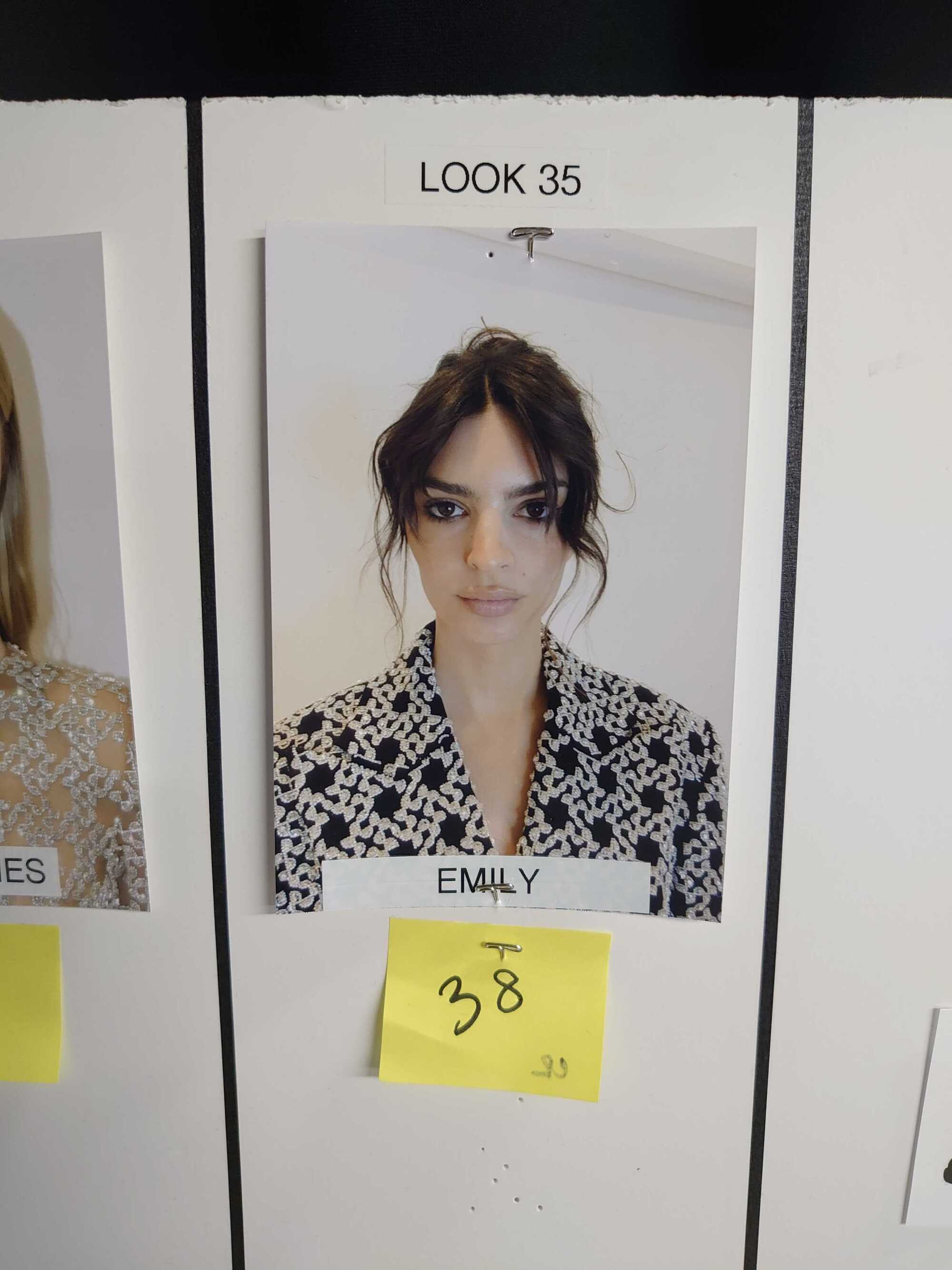

Emily Ratajkowski knows that everyone is looking at her. Or maybe she doesn’t, because she’s never not being looked at. On Instagram, walking down the street or here, backstage at a New York Fashion Week show. All those eyes, desiring, judging, calculating.

For the record:

1:48 p.m. April 9, 2023This story was updated to reflect that in the legal disputes involving Bear-McClard, two of the allegations were of sexual misconduct not non-consensual sex.

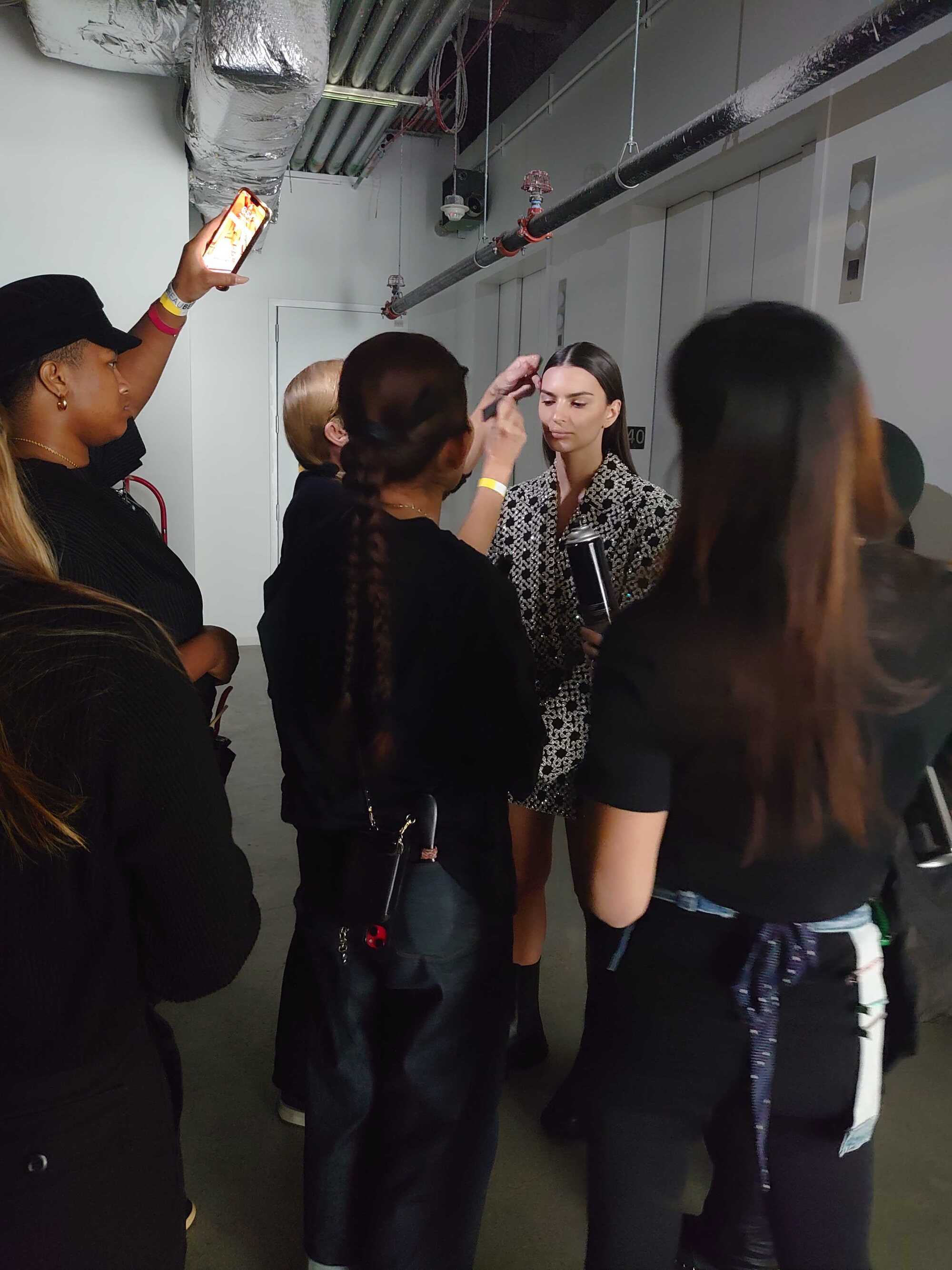

As a model who rose to fame in the Instagram age, and wrote a bestselling book about what it was like, she has learned to deal with the collective gaze by turning inward. She stands at the back of a line of 34 other models, in position to close the Simkhai runway show in an oversize bedazzled blazer and combat boots. Photographers approach her, and she poses dutifully.

“Every angle is giving. Sickening. She’s fierce,” one says. She doesn’t respond, just keeps offering different angles of her face to the camera. The other models, newer to the industry, gather in clusters, excitedly discussing the other brands they’re walking for in the coming days. Ratajkowski exchanges pleasantries but doesn’t join any of the conversations.

Who are the people shaping our culture? In her column, Amy Kaufman examines the lives of icons, underdogs and rising stars to find out — “For Real.”

An onlooker is staring at Ratajkowski while trying to pretend she isn’t. “I didn’t know she was gonna be here,” the woman whispers to a friend. “She’s, like, one of the top five models.”

Ratajkowski doesn’t hear this. It’s like there’s an orb around her, a protective shield she has generated for self-preservation. At age 31, the sense of calm is new to her, something that has emerged in the wake of the dissolution of her marriage and becoming a single mother.

“I don’t even feel my heart rate go up in the way that I used to,” she says. “The anxiety doesn’t hit me so much, because I’m very clear on how I see the world and what the truth is.”

That truth, as the world is learning, is dark. On March 29, sexual misconduct allegations against her estranged husband, “Uncut Gems” producer Sebastian Bear-McClard, became public. In statements obtained by Variety that were made in connection with a legal dispute, Bear-McClard was accused of sexual misconduct and grooming, some of which allegedly occurred while he was married to Ratajkowski.

After she filed for divorce in September, gossip blogs rampantly speculated that she’d ended the relationship because Bear-McClard cheated on her. But she never addressed the rumors with any of the hundreds of outlets that track her every move.

Instead, she moved on, into a new place in New York City’s West Village that she shares with her best friend from high school and into a high-profile dating life. She reportedly went out a few times with Brad Pitt. By November, she and Pete Davidson — fresh off his split with Kim Kardashian — were going to Knicks games together. Shortly after New Year’s, she started seeing comedian Eric André; that lasted a couple of months. Then, in late March, photos emerged of her and Harry Styles making out. She was on her tiptoes, arms wrapped around his neck as he pushed her against a van in the middle of a street in Tokyo.

None of which offers the slightest hint that she has been living through what she describes as one of the “most traumatic experiences of [her] entire life.”

Over two months of conversations, Ratajkowski dances around the edges of why her marriage collapsed. In 2018, she’d married Bear-McClard after just two weeks of dating, throwing on a jumpsuit from Zara and heading over to City Hall. Three years later, they welcomed a son, Sylvester.

Sly, as Ratajkowski calls him, is the reason she won’t go into detail about the “horrifying” year she’s had; she doesn’t want to jeopardize gaining custody of the 2-year-old.

“I’m scared,” she says. “I’m learning that outspoken women don’t often get their children.”

Biting her tongue doesn’t come naturally to Ratajkowski, especially now, when she feels she’s finally finding her voice. In 2021, her first book, “My Body” — a collection of unexpectedly frank essays exploring beauty, feminism and power — became a New York Times bestseller. That led to “High Low With EmRata,” a podcast she launched in October where she employs the same candor to interview sex workers, investigate ethical nonmonogamy and ponder the etymology of the word “toxic.”

At this point, it’s difficult to recall that Ratajkowski first became famous 10 years ago for dancing topless around Robin Thicke in the controversial “Blurred Lines” video. Since then, she’s become one of the most sought-after supermodels in fashion, walking the runway alongside Gigi Hadid and Kendall Jenner and serving this season as the face of Versace and Tory Burch’s campaigns.

On Instagram, where she has 29.9 million followers, she still shares provocative images of her body — adjusting a thong bikini, holding her naked breasts to show off her tan lines. She’s sexy, but she’s cheeky about it: “me coming out of a sad girl day to check in on the step father applications in my DMs,” she captioned one TikTok video of herself shaking her behind in the middle of the street.

After years of trying to explain how her last name is pronounced — the “j” is silent, so on TikTok she once posted a helpful emoji guide: 🐀 🐄 🎿 — she’s come to embrace the culture’s nickname for her: EmRata. Maybe the playful shorthand has something to do with why so many young female fans have developed parasocial relationships with her.

That, or that she offers them the fantasy of the glamorous “hot girl” life — the world travel, the famous friends, the designer clothes — while also giving them glimpses of its more sobering realities.

“I feel like I’m coming into myself,” she says. “Being able to assert what I want — that feels like it just started. My life as a creator and not as a muse.”

Who the hell would cheat on Emily Ratajkowski?

That was the question that kept arising online in the wake of her separation. She wasn’t surprised by the discourse, but it made her sad, sad that people believe beauty somehow protects women from pain. “The world is pretty brutal to women, no matter what they look like,” she says.

It’s February, and Ratajkowski has just finished recording an episode of her podcast with “Queer Eye” star Jonathan Van Ness. Sony Music Entertainment, which produces the program, has set up a studio space for her in the company’s office overlooking Madison Square Park.

Earlier in the day, paparazzi caught her walking on the street with André. She’s talked about this on her podcast — how dating in the public eye has complicated her relationships. before she knows whether she’s even into someone, pictures of her on a first date go viral. And then TikTok does what TikTok does, commenting on whether or not she’s out of a dude’s league or continuing to question the allure of Davidson to beautiful women.

“Even my friends were like, ‘What was that like?’” she says, referring to her outings with the “Saturday Night Live” veteran. “I actually don’t understand it. People are so perplexed by the idea that a man might just be respectful to women and treat them like people and thus be easy to go out on dates with.”

Dating around is new to Ratajkowski. In “My Body,” she wrote about how after a night of taking vodka shots at age 15, she awoke to a boy raping her. She was so terrified that she became a serial monogamist, seeking safety in partners she hoped would protect her. “Men do usually respect other men’s presence in women’s lives,” she said.

She feels more equipped to protect herself now. She’s OK with telling men “no,” voicing her dislikes, making them mad. “But I think a part of me is still scared of men,” she admits.

There are plenty of stars who were music-video vixens before making it big: Alicia Silverstone was Aerosmith’s muse in the ‘90s, and Courteney Cox boogied with Bruce Springsteen pre-”Friends.”

Ratajkowski often drops bombs like this in conversation, but they’re delivered in the same cadence with which she shares where she got the vintage belt she’s wearing. She’s eager to debate thorny issues, and she’s not withholding, save for spilling on her Tokyo make-out session with Styles. But her mode of expression is mellow. She’s not one to yell or laugh uproariously, which has led some people — especially men — to label her as unemotional.

One date recently remarked on how she was “stoic in the face of adversity,” which took her by surprise. “I think of myself as extremely tender,” she says. “I’m like, ‘Have I been hardened?’ I think I’m just a little less scared now, basically, of the world. So maybe that comes off as unemotional.”

Less scared of the world but also less willing to put herself into positions where she is vulnerable to “power dynamics and the power that is held by boys clubs.”

That’s a big part of why she‘s basically quit acting. Her last audition was for “Triangle of Sadness”; the part went to the late Charlbi Dean Kriek, but Ratajkowski had already started to sour on Hollywood. After her first role in a major film, playing Ben Affleck’s mistress in 2014’s “Gone Girl,” she and her team began working on finding parts to prove she was a “serious actress with longevity.” She had some success, playing opposite Zac Efron (“We Are Your Friends”), Amy Schumer (“I Feel Pretty”) and Marc Maron (“Easy”).

“But I didn’t feel like, ‘Oh, I’m an artist performing and this is my outlet.’ I felt like a piece of meat who people were judging, saying, ‘Does she have anything else other than her [breasts]?’” Ratajkowski says.

In early 2020, tired of making herself “digestible to powerful men in Hollywood,” she fired her acting agent, commercial rep and manager.

“I didn’t trust them,” she says. “I was like, ‘I can handle receiving phone calls. I’m gonna make these decisions. None of you have my best interest at heart. And you all hate women.’”

There’s an essay in “My Body” where Ratajkowski writes about going to a WME party. She wasn’t having a good time — guests kept approaching her, asking for photos — and she felt like her husband was abandoning her. The couple was bickering when Bear-McClard’s agent, “clearly drunk,” told Ratajkowski she was so famous that she was “like Pamela Anderson before the hep C.”

She was livid at the agent and her husband for dragging her to an event filled with people like that.

“I thought about the way that [Bear-McClard] had glided through the room, a room full of men who only two years before had been kissing Harvey Weinstein’s ring and encouraging their young female clients to take meetings with him in hotel rooms,” she wrote. “I hated that my husband was at all connected to these men.”

Connected, she would learn, by more than just association. The revelations of her husband’s alleged treatment of other women only confirmed her worst suspicions, that the entertainment industry still roils with the same exploitative forces that allowed Weinstein to rape and brutalize for so long.

The ex-fiance of reality star Lala Kent faces the collapse of his company amid a trail of lawsuits, civil fraud charges and allegations of abusive behavior.

“And maybe that’s why right now I’m not really interested in men’s POVs,” she says. “Because they were lies. And I don’t mean infidelity. This is a f—ed up world. Like, Hollywood is f—ed up. And it’s dark.

“Obviously, it would be nice to be with somebody who’s in the industry or understands it, but I don’t think I can. That was what that essay was about ... I had a hard time even being at a party like that. But then having a part of me that was so connected to it was even harder.”

The power dynamics may not be very different in modeling, where the CEOs of the major fashion brands are also primarily white men. But on set, she says, she’s interacting mostly with queer and femme-presenting people, which makes her feel safer.

Safer now, anyway. When she started out in the industry, Ratajkowski says, she was often put into situations that upset her. She’d be at a casting session, and a model a few years older would befriend her. A few days later, her new friend would invite her to dinner at a trendy restaurant, maybe the back room at Nobu.

When she arrived, she’d see a group of young women like herself, “stiffly looking around at each other in little outfits.” Many would be from other countries, just starting out without much money and literally hungry. After a lavish dinner, the party would move to a club.

And that’s when the men would appear.

“Disgusting, 40-plus men showing up in black cars,” Ratajkowski says. “There’s no direct explanation of what is being traded for what, which is why it’s so creepy. They call themselves party promoters, but, like, party promoters or sex traffickers?”

Though she stopped going to these so-called networking dinners years ago, she says she constantly hears from young models who end up in similar scenarios they aren’t anticipating.

Speaking out about her experience in Hollywood has drawn admiration and derision. “Every guest on Emrata’s podcast is like ‘Sex work is work. We love sluts. I hate sex and I’m scared of men,’” went one tweet that Ratajkowski reposted to her feed in February.

Which, no. Because, as she says, she is “out here in the streets with men.” Just ask Styles. Or the makeup artist at the Simkhai show in February, who had to cover up some “little giveaways” on her neck — presumably from André, per the timing of paparazzi photos — before she hit the runway.

Ratajkowski does enjoy the company of men — at least those of her choosing — and but that doesn’t mean her feelings toward them aren’t complicated. She still derives a lot of confidence from men, which she isn’t proud of. A day before the fashion show, she says she had to ask a guy she was dating — again, likely André — if he thought she was pretty.

He’d talk about the women he’d dated in the past, commenting on how gorgeous they were. But he’d never said anything about the way Ratajkowski looked.

“So I said, ‘What do you think of me?’” she recalls. “And he was like, ‘Are you serious? You’re a famous model.’ I was like, ‘Wow, you don’t get it.’ I need to know that you are specifically attracted to me. Beauty is totally subjective. I don’t care how much it’s validated by a standard.”

Dating, she’s realized, gives her a perspective on herself she’s lacking; watching men react to her, and then examining her feelings about those reactions, helps her tap into her “super-womanness.” “It’s almost like they hold up a mirror,” she says, “and that helps me feel like the confident person I really need to be to be able to do the work I do.”

By March, however, she had ended things with André and said she wasn’t dating much.

In L.A. for the weekend, modeling in the Versace show, she had just returned to her hotel after a fitting for the dress she’d wear to the Vanity Fair Oscars party the following night. And she was tired.

“I’m really just not thinking about guys,” she said. “I’m working, I’m a single mom. I’ve been so busy that it’s easy not to think about.”

Two weeks later, the photos of her and Styles hit. There are even more headlines than usual, partly because he is the most coveted young pop star on the planet, but also because Ratajkowski is friends with his ex-girlfriend, actor and director Olivia Wilde. Pictures of the two women dancing together at one of Styles’ concerts in June start resurfacing, as do rumors on the gossip site DeuxMoi that the trio had once had a threesome.

“There’s a million insane, inaccurate things about my relationships [that are said],” Ratajkowski says in a voice note she sends from Japan. It’s early morning there, and she’s jet lagged, giving Sly a bath. He splashes water in the background, saying “mama” and trying to get her attention.

“I’m definitely still not thinking about guys,” she says, letting out a soft laugh. “Although, yeah. You know, sometimes things just happen.”

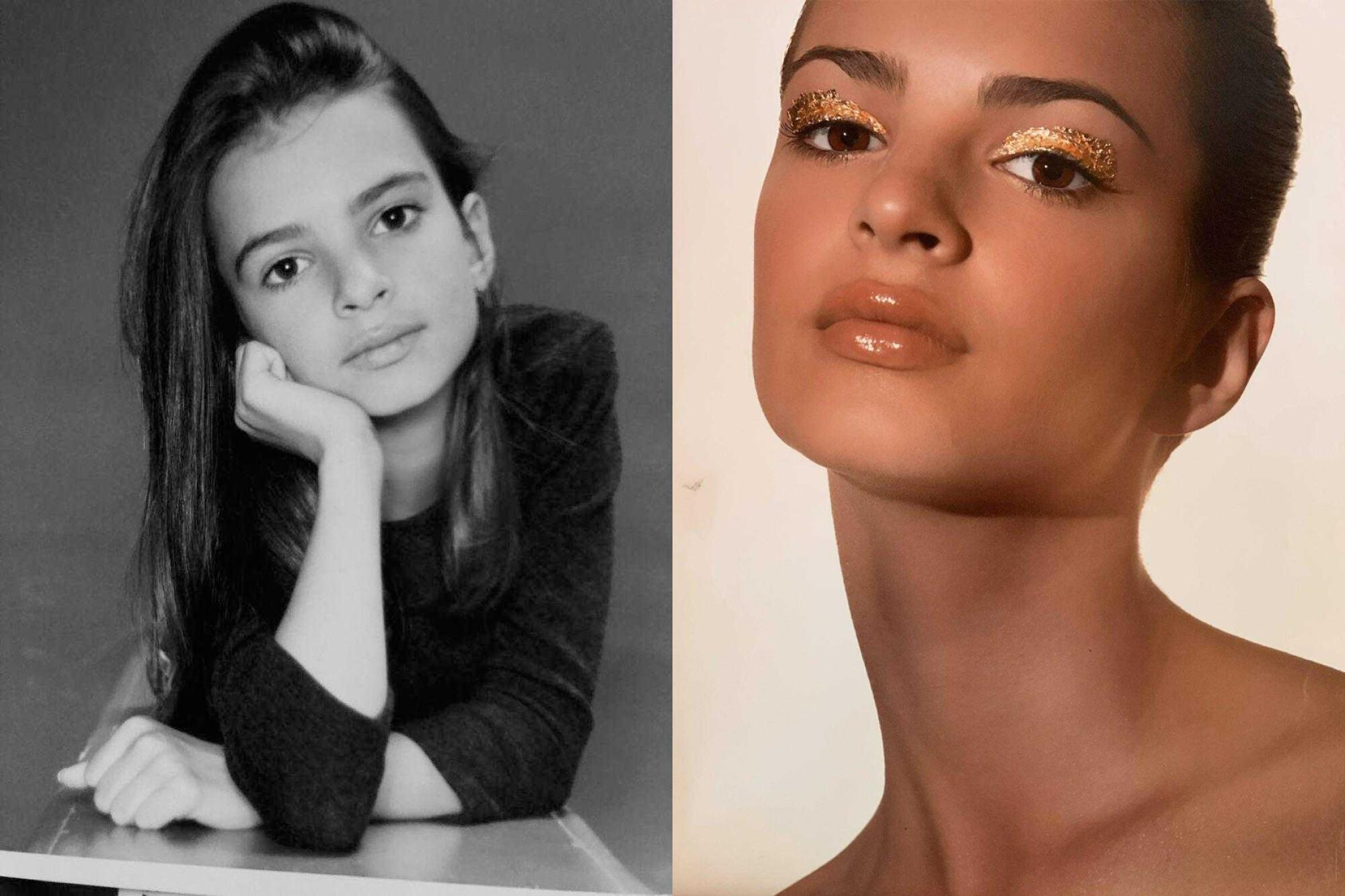

Ratajkowski was 9 when she first realized she was beautiful. She was in drama class and started crying. An older girl took note, announcing: “Ugh, she’s even pretty when she cries.”

In “My Body,” Ratajkowski recounts how beauty was prized by her mother, so much so that as a girl, she’d lie in bed and nightly pray to be beautiful. She clocked all the remarks her mom made about female celebrities and their looks: “Marilyn Monroe was never really beautiful.” “I don’t get Jennifer Lopez. I guess men like her.”

She was an only child, growing up in the home her father built in Encinitas. John David “J.D” Ratajkowski was a high school art teacher with no background in architecture, but he was handy, the kind of guy who made his own canvases and got into bronze work.

Her mother, Kathleen Balgley, was a college English professor who once traveled to then-communist Poland on a Fulbright fellowship to teach American literature. While abroad, she learned that her father — who had been born in Belarus — was Jewish and had hidden his identity for decades due to fear of antisemitism. Balgley would go on to convert to Judaism and write a book about her experiences in Poland before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

At 48, Drew Barrymore has survived divorce, quitting alcohol and leaving her beloved Los Angeles. Now she’s trying to embrace herself as she forges ahead in a new direction — talk show host.

When Ratajkowski was a child, her parents instilled her with a love of reading. “My mom talked about Toni Morrison as if she was, like, God,” she says. Ratajkowski got respectable grades, especially in English, but she never wrote for herself. At age 7, she said, she tried to start a journal. But on reading an entry back to herself, she felt that the writing wasn’t strong enough and abandoned it altogether.

When she began to model at age 14 — first in teen magazines like Girls’ Life — her parents proudly shared images from her photo shoots on Facebook. A couple of years later, she signed with Ford Models and started to drive to L.A. for auditions, landing a two-episode role on Nickelodeon’s “iCarly.” But she didn’t publicize the gig to her friends. “I thought I was too cool,” she says. “I was like, ‘I’m an artist. I smoke weed. These clothes are embarrassing.’”

At San Dieguito Academy, which she says had “kind of a ‘Euphoria’ high meets ‘Lords of Dogtown’ vibe,” she was popular but didn’t have a niche. She’d always say she was a “jack of all trades, master of none” because she thought she was so mediocre at everything. When she got into UCLA, she decided to major in art. She liked making mixed media — photo collages combined with drawing. Her relatives disapproved: “What is she going to do with that?”

But Ratajkowski would stay only four quarters, dropping out when her modeling career took off.

“My parents were worried, but what were they gonna say? Don’t make this money? Don’t travel?” she says.

She went to New York, but every agency passed on her because of her height — 5 feet 7 inches.

“At the time, you’d only make one or two exceptions for a shorter model per show,” says Katie Grand, who founded the fashion magazine Love, which put Ratajkowski in her first editorial spread in 2015. “It was always a bit archaic; for a very long time, it was ‘the model fits the clothes,’ rather than ‘the clothes fit the model.’”

Grand helped get Ratajkowski cast in a Marc Jacobs show, and slowly, high-end designers began to consider working with the fledgling model.

But even as her prospects grew, she found herself depressed. At age 27, she felt as if she were already having an existential crisis. She’d started modeling because she wanted to make money. Now, she’d made some. “What are you worth?” she asked herself.

She started therapy, drilling into what really made her happy. It was reading, she realized. Could she be a writer? For so long, she’d been paralyzed by the fear that she’d never be as good as those she admired. So she started slowly, writing essays for herself. But she couldn’t tell if they were decent, so in 2019, she decided to reach out to writers she looked up to — Stephanie Danler, Ariel Levy, Chloe Caldwell — DMing them on Instagram and asking if they’d be open to reading her early drafts.

Danler, who had written an essay in the Paris Review that’d caught Ratajkowski’s attention, was unfamiliar with the model when the message arrived.

“I sent a screenshot to my sister and asked: ‘Why does this person have 28 million followers?’” says Danler, best known for her books “Sweetbitter” and “Stray.” “She sent me an essay, and I could see that she had a voice and that she knew how metaphor worked. I thought it was very ambitious and gave her a few notes on it.”

A few months later, Ratajkowski sent Danler a complete rewrite. “That’s when I was like, ‘Oh, this woman is a writer.’”

The self-esteem boost was enough to convince Ratajkowski that she was ready to start shopping for a literary agent. Schumer offered to connect her with David Kuhn, the rep who had secured a reported $9-million advance for the comedian’s memoir. Like Danler, Kuhn was unfamiliar with Ratajkowski, but he told Schumer he’d talk with her as a favor. Before meeting, Ratajkowski offered to send him her material to make sure he was interested.

“I expected to get a few pages, and she sends, like, 90 pages. And I was blown away by the writing,” says Kuhn. “I’m used to celebrities coming to me and saying they want a book deal without anything on paper, nor any idea what they want to say. But Emily is the real deal. She was writing about issues most women can relate to but also writing about fame and celebrity and the power that comes from that with a unique insider perspective.”

After “My Body” was published — and Ratajkowski scored a seven-figure advance, although “not anywhere close to what Amy got” — she decided she wanted to further the conversation about feminism and how women were treated in male-dominated spaces. She’d been approached years ago about doing a podcast, but she didn’t yet have a take that she thought would differentiate her from “every other bitch with a podcast.”

So in 2021, she tracked down the UTA agent she’d previously blown off, Oren Rosenbaum, who helped Alex Cooper sell the wildly successful “Call Her Daddy” to Spotify. Ratajkowski says he told her he’d work with her on one condition: that she put out two episodes per week.

“He was like, ‘You have to build this out as a giant library and own the IP,’” she recalls. “‘If you only want to make 30 episodes a year, I don’t think we should do this.’”

A $60-million Spotify deal made her the highest-paid female podcast host on the planet, now ‘Call Her Daddy’s’ Alexandra Cooper is fathering a generation.

Ratajkowski agreed. On a Tuesday episode, she’d interview guests she found intriguing, such as actor Julia Fox, stylist Law Roach and designer Donatella Versace. For the Thursday installment, she’d take to the microphone solo, posing questions about OnlyFans, empowerment and aging. to investigate through her own research — citing passages from such feminist authors as Roxane Gay and Melissa Febos.

In May, she began pitching the project as a female-led podcast for millennials and Gen-Z, “Fresh Air Meets Call Her Daddy.”

“I was like, ‘OK, EmRata is this one-dimensional figure that people know from social media and bikinis,’” she says. “‘And then I have a book of essays, or you see me on a runway and then in sweatpants with my dog and my baby. All these parts of me exist.’ I wanted a way to speak to the multifaceted parts of womanhood.”

As a host, Ratajkowski has a gentler presence than the brassier personalities — Cooper, Joe Rogan, Dax Shepard — that currently rule the podcast charts. During interviews, she rarely talks about herself, and she doesn’t like asking questions that make guests uncomfortable.

“I’m a little bit too respectful, and I’m working on that,” she acknowledges. “I feel like if someone’s coming on my podcast, unless they’re offering information up, I don’t like to push. Julia Fox said before coming on that she didn’t want to talk about [dating] Kanye West, so I didn’t ask. Which is probably wrong. Like, I should have gotten her to talk about him.”

Ratajkowski’s hope is to eventually create a full-blown media company with more audio projects, documentaries and maybe even a book club. She admires what Reese Witherspoon has been able to create with her female-aimed multiplatform media company Hello Sunshine but hopes to appeal to a younger generation, so she’s calling the business Bitch Era Media.

“The name is about not worrying about labels like that,” she says, “or my emotions being easily digestible for other people.”

There are plenty of people who still resist Ratajkowski as a three-dimensional figure, who think she benefits from the same system she’s criticizing. And she gets it. She still feels unsure of the right way to share her body with the world. But if she hadn’t played the game, hadn’t, as she says, posted near-nude photos and “gotten a huge Instagram following,” would she have even been able to gain a platform to talk about the things that matter to her?

“I hate the idea that because, like, Sydney Sweeney posts sexy pictures and has a bikini line that she is somehow hurting women,” says Ratajkowski, referring to the “Euphoria” star. “Can we stop blaming Sydney Sweeney? Or the woman who had an affair with [Maroon 5 frontman] Adam Levine who everyone was so mad at instead of him? When the power dynamic in the world is so skewed, why are we putting all this weight on women?”

These are ideas Ratajkowski hopes to keep probing in further writing, although she’s not doing much of it at the moment. She feels like she needs to process the last year before writing about it. She doesn’t like writing that feels like therapy, the kind that asks the reader how the writer should feel.

And then there’s Sly. He’s currently living with her full time, although he sees Bear-McClard a few times a week. In a way, she’s sort of felt like it was the two of them — her and Sly — since he was in her belly.

Toward the end of her pregnancy, she was becoming more and more eager to go into labor. So one night, she sat on the couch and placed both her hands on her stomach and talked to her unborn child.

“I’m so scared, and I know you’re so scared. But we’re going to do this together, and I promise to keep you safe. Let’s do it. I want to meet you.”

A few hours later, she was in labor.

The experience gave her faith in her intuition, in her ability to control things. The subsequent breakup of her marriage, while devastating, reinforced similar notions, validating things she’d long suspected but pushed down. There’s a relief now, she says, returning to herself.

“It feels beautiful, like I’ve awoken,” she says. “It’s kind of like the archetype of Pygmalion, the classic story of the mannequin or statue coming alive. There’s something that’s been created in a man’s perfect image, and then it takes on its own life.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.