Mario’s ‘dad’ Shigeru Miyamoto on ‘The Super Mario Bros. Movie’ and watching his creation grow beyond him

)

For nearly four decades, a plump plumber in red overalls named Mario has been a universal mascot for video games.

But just who is Mario? Over the years he’s been the savior of the surreal Mushroom Kingdom, a kart racer, a tennis player, a golfer, a brawler and more. He’s transformed into a cat and a raccoon-like critter, and can become possessed with the power to shoot fireballs, all thanks to various plants or edibles.

Since the release of the game “Super Mario Bros.” in 1985, Mario has been a star — he’s also consumed stars to turn into a glowing, impenetrable figure. Mario is the brainchild of Shigeru Miyamoto, the game design master who, in addition to “Super Mario Bros.,” has shaped “Donkey Kong” and “The Legend of Zelda,” among many other pivotal games. Mario says little, having spoken for most of his gaming life in catchphrases — “Let’s-a-go!” or “Mario time!” Asked once what was Mario’s secret, Miyamoto told The Times, “It was the big nose and the mustache.”

But those are character attributes rather than character development. Even so, Miyamoto has seen his creation outgrow video games. Mario today anchors theme park lands at two Universal Studios parks, including one in Hollywood, and is now the protagonist of a major animated film (in theaters Wednesday). He’s a weird little dude, a potbellied character who’s proficient at running and jumping but whose full life and backstory has long remained a mystery. Can Illumination’s “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” answer, at long last, just who is this odd working-class man who has come to symbolize an entire medium?

“I do get questions about why this mustachioed man is so popular. Before I used to answer it’s because of the games that he’s been in, and the fact that the gameplay allows the player to see Mario as themselves, as an avatar of themselves,” Miyamoto tells The Times. “But as I see the manifestation of the park and now the movie, Mario has become a character who has always been there. There’s people beyond their 50s who knew Mario and grew up with Mario.”

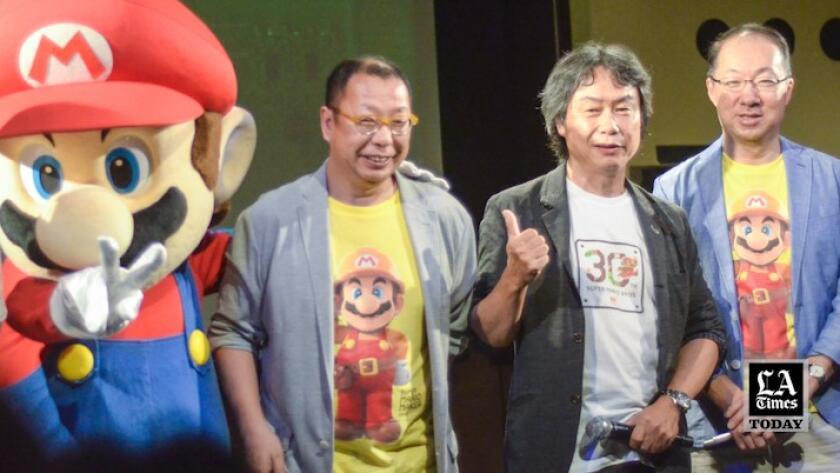

‘Super Mario Bros.’ creator Shigeru Miyamoto on the importance of play: A visit with the game design mastermind at Universal Studios’ Super Nintendo World.

Such a realization was freeing when it came to “The Super Mario Bros. Movie.” We don’t need to know every detail about Mario’s life, because, Miyamoto reasons, we just want to live in his world. The Mushroom Kingdom, as odd as its wobbly creatures and fireball-sprouting flowers are, is one we now see as familiar. The most recent game in the “Super Mario” series, after all, “Super Mario Odyssey,” has sold more than 25 million copies, but Mario is also the namesake character of “Mario Kart 8 Deluxe,” which has sold 52 million copies.

“When we see Mario in the theme park and now the movie, even though there’s no interactivity or mechanism that provides gameplay, it’s grabbing people who are fans and inviting them into this world,” Miyamoto says. “Seeing them enjoy their time in the world of Mario was eye-opening.”

As a co-producer on “The Super Mario Bros. Movie,” Miyamoto says he took a vocal role in bringing his creations to theaters. He had to, as the 1993 live-action film is often seen as an embarrassment to the brand, and was used for years as an example that video games were difficult to impossible to adapt. That myth has been dispelled today, thanks in part to the HBO series “The Last of Us” and Riot Games’ “Arcane,” an animated take on “League of Legends.”

“The Super Mario Bros. Movie” co-producer — and the founder of CEO of Illumination Entertainment, Chris Meledandri — says Mario’s abstract history had to be used to the studio’s advantage.

“When you think about making the transition between a character who is an avatar and a character who is going to occupy the center of the story, the degree of Mario’s relatability becomes very important,” Meledandri says. “While you’re not actually playing him as an avatar, you are relating to him and seeing the world through his eyes.”

Relatability is the key to Mario’s long-term success. In the film, Chris Pratt voices the character with an enthusiastic, not-quite-Brooklyn, not-quite-Italian accent and speaks almost entirely in cheery optimism. It’s not a surprising choice, as Mario has long been a plucky, can-do underdog, an unlikely hero whose princess was often just out of reach and clearly out of his league. But Mario is relentless in the pursuit of his goals, getting back up every time he gets knocked down — or shrunk down.

“It’s the very fact that he is not your typical superhero that makes him such an interesting movie character,” Meledandri says. “He’s so relatable. He’s an Everyman character. He never gives up. He always keeps coming. Those qualities make for a very compelling central character.”

The question, then, was put to Mario’s father: Which of Mario’s personality traits does the 70-year-old see in himself?

“I think part of it is the idea that Mario never gives up,” Miyamoto says. “And he’s kind of got this shy side to him. When all the attention is focused on him, he’s a little bashful and doesn’t maybe want that. That speaks to me. He might seem brave, but that’s still a fundamental core essence of his character.”

No damsels here

Mario, originally known as Mr. Video for video games and then Jumpman, was first seen in Nintendo’s 1981 surprise arcade smash “Donkey Kong,” which sprang from the imagination of Miyamoto when he was a young staff artist at Nintendo. Miyamoto has said that Mario was inspired by comic book characters of the era, a hero who could fit comfortably in whatever setting his creators dreamed up.

With limited pixels — “16 dots by 16 dots” — Miyamoto wanted a character that was instantly recognizable, resulting in our slightly chubby champion-to-be Mario, a name Miyamoto took from a former Nintendo of America warehouse landlord. When “Super Mario Bros.” arrived in 1985, it was a revelation. Prior Nintendo games were generally set against a black background, a setting chosen in part for its simplicity and, in part, Miyamoto says, for the contrast it provided.

“The idea that we were using black backgrounds was due to the fact that the color options available, from a technological perspective, was limited, and in games, the idea of having collision was very important,” says Miyamoto, speaking through a translator, and then demonstrating, with his hands, blocks breaking apart. “Black backgrounds made it easier to decipher when collision happens, but with the development of ‘Super Mario Bros.,’ the theme was having a grand adventure — in the sky, on land and on sea. So we decided to take the bold step and use brighter colors.”

“Super Mario Bros.” was a fully fleshed-out world. Inspired by the playgrounds of Miyamoto’s youth, the game was a strikingly bright digital world centered on curiosity. The first level of “Super Mario Bros.” remains a master lesson in game design: In front of us is a walking mushroom. Can we touch it? No, but maybe we can jump on it? And what about this blinking box? Maybe hit it with our head? And now there’s a polka-dotted mushroom streaking away from us. Run after it?

Illumination’s film aims to capture the radiant Mushroom Kingdom, a place where pretty much anything can happen and even torpedo-like projectiles have anthropomorphic qualities. But there were some liberties taken. We learn, for instance, that the universe of “Donkey Kong Country” is nestled closely to the Mushroom Kingdom, and the famed Rainbow Road from the “Mario Kart” games acts as a sort of interstate among the universes.

When it came to fleshing out the characters of the world, Mario’s nemesis Bowser (Jack Black) is played as a lovesick and obsessed heavy metal balladeer, whose fascination with Princess Peach (Anya Taylor-Joy) sends him on a quest to conquer her kingdom. Donkey Kong (Seth Rogen) is less a villain to Mario and more a light foil, an image-focused figure who doesn’t want Mario to one-up him. But the most striking reinvention is that of Peach, who here sheds her long-outdated damsel-in-distress roots and instead acts as Mario’s teacher, introducing him to the ways of the Mushroom Kingdom and showing him how one can platform — run and jump — through the universe.

“We felt the opportunity here was to take the next step and really activate her and give her her own agency and her own power and her own heroism,” Meledandri says.

Thirty years ago a plump little plumber in red overalls revolutionized gaming.

In the games, Princess Peach was Mario’s oft-kidnapped belle, a tactic that was used as an excuse to launch the game with a thin plot. In the film, she’s far more formidable than Mario, and can even come to his rescue. Nintendo games have over the years moved beyond the trope, regularly making Peach a playable character. “Odyssey” went further, as the ending of the game saw Peach spurning Mario and going off an existential solo quest to explore the world. If you spent the majority of your adult life in imprisonment, you’d likely want some me-time, too.

Miyamoto, then, said he was on board with Peach’s reinvention in the film, requesting only that she adhere to certain looks that were defined in the games.

“It was really making sure that the people, the consumers, the customers, the players who have had a lot of experience aren’t going to be disappointed when they see Peach,” Miyamoto says. “The only parts [where] I was involved in the discussion was to make sure this character appears in this order so it doesn’t disappoint the audience’s expectations, and making sure which facial expression comes out.”

Miyamoto’s creations have now grown beyond him and taken on, well, a life of their own. Miyamoto says he does his best not to be precious. “Within Nintendo, there are people who are very protective of Mario, but for me, Mario’s interactions with new things that come up have helped him evolve to what he is now,” he says. But adhering to tradition, he acknowledges, hasn’t hurt Mario’s longevity.

“Back in the day, we had to work around the limitations we were given. For me, it was very important that we create something truly unique and new,” Miyamoto says, reflecting on Mario’s creation. “I start with drawing, and then dropping into dot art. But even then — this 20- to 30-year-old, mustached and slightly round [character]. Did I have confidence he was going to be a popular character? No, I didn’t. But looking at it now, we don’t have any technological limitations. But seeing Mario come to life, and looking at Mario, this is a character that maybe you could find somewhere in the real world.”

There’s a lesson in there. As wild as interactive entertainment can be, and as many magic mushrooms as Mario consumes, interactive entertainment isn’t just about winning, competitiveness or combat; it’s almost always about seeing ourselves in the story.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.