Review: The Hammer pulls off a marvelously orchestrated show of Bridget Riley’s drawings

In 1949, when she was 18, Bridget Riley began formal art study at London’s Goldsmiths’ College. A businessman’s daughter from the agricultural countryside, she had come to the big city, then struggling to rebuild from the recent cataclysmic war’s devastation, in order to learn to draw. Drawing, she later said, is where she needed to start if she was going to be an artist.

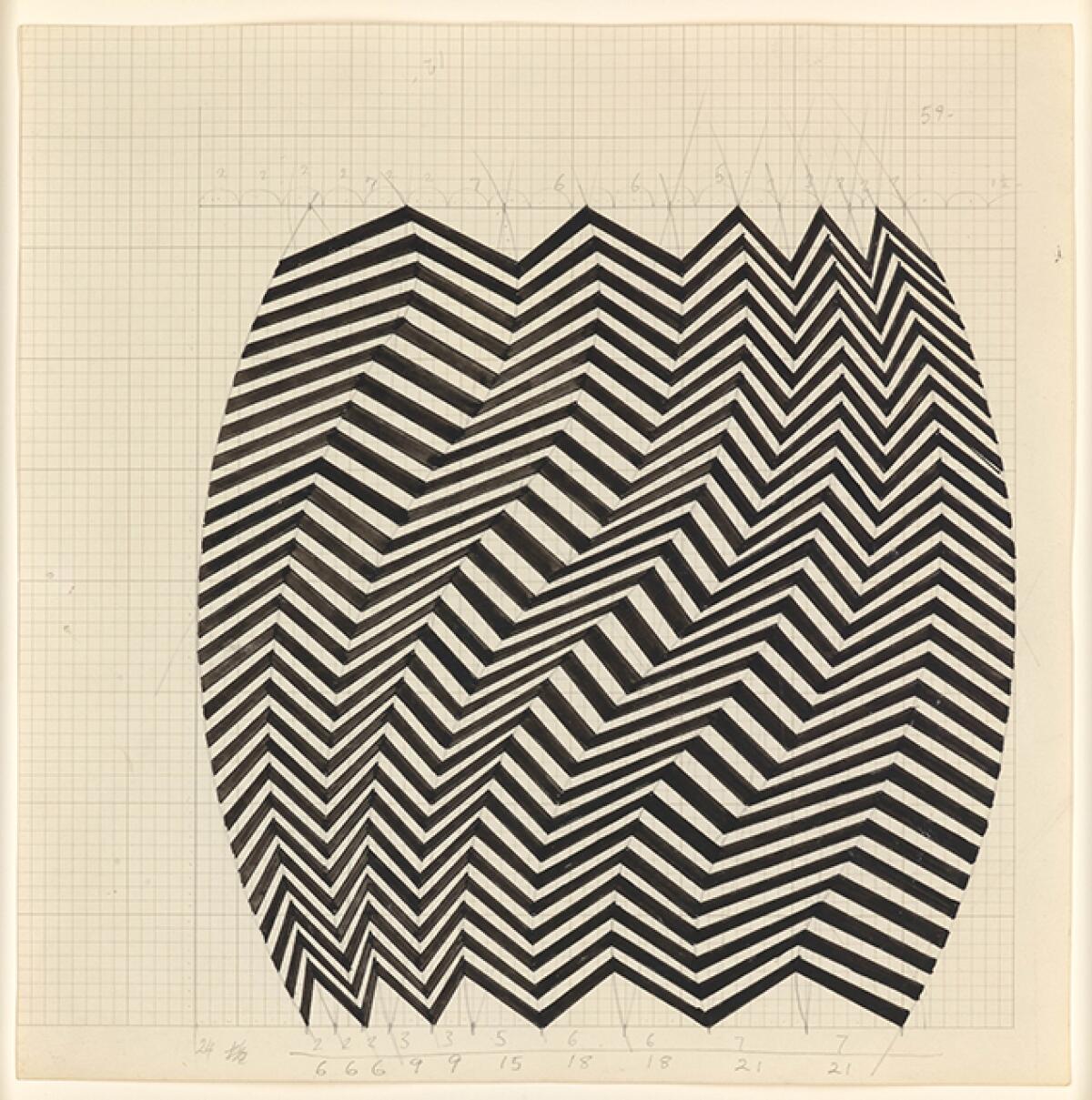

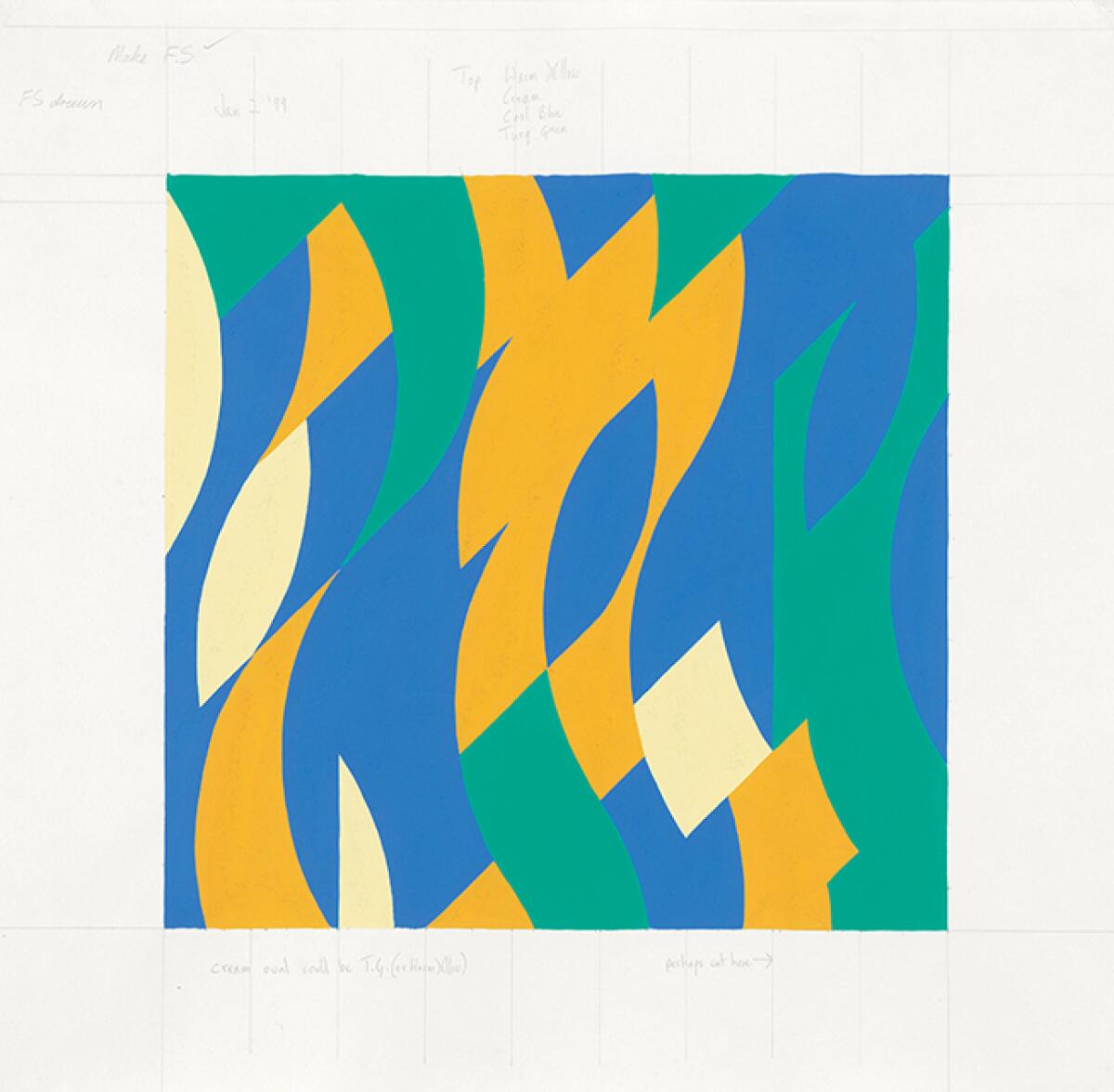

An engrossing exhibition at the UCLA Hammer Museum demonstrates how right she was. “Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio” features 24 little-seen figurative and landscape works in pencil, crayon, oil and pastel from the 1940s and ’50s, plus 65 mostly geometric abstractions from 1961 and after, for which she is today well known. The drawn abstractions became patterns for paintings. (Riley made the drawings, while assistants usually executed the paintings based on them.) One graced the catalog cover of “The Responsive Eye,” a sprawling — and not very well received — Museum of Modern Art group exhibition in 1965, sometimes dismissed as “that Op Art show.” In it, Riley emerged as a singular voice, using line, shape and color to fabricate a sense of motion in space.

The marvelously orchestrated Hammer show tells a story of how she got from representation to abstraction, and that it happened in a surprising way. Color was the pivot, Post-Impressionist painter Georges Seurat the instigator.

Seurat’s atmospheric drawings of people and places using hard, waxy Conté crayon coax luminosity from smoky darkness. Riley went after similar effects in rendering images of a young girl absorbed in a book, her head and body an assembly of blocky forms in gradations of gray, from pure white to deepest black, or of trees rising as hulking forms silhouetted along a riverbank, almost like reclining bodies.

“Recollections of Scotland” is a series of dark gray curves against the sheet of white paper, like ripples from a pebble dropped into a pond, ending at a black shape suggestive of night sky, while adjacent stacked bars that reduce in size as they climb the page create an unexpected sensation of pictorial depth. Where the visually receding bars end, a crisp white rectangle becomes uncanny architecture, transforming all those contiguous curves into a suggestion of shrubby landscape.

The instructive leap, though, comes in the show’s single representational oil painting, accompanied by three related drawings that focus on tonality, line and color. “Blue Landscape” (1959) shows blocky buildings beyond rolling hillocks and behind a screen of trees. (The composition loosely recalls Cézanne in Provence.) Riley’s painting is modest in size, 40 inches by 30 inches, and it’s largely assembled from short, confetti-like daubs of color — blue interspersed with green, gray, ocher and taupe, plus an occasional jolt of red-tile roof. She’s adopting and adapting Seurat’s Pointillist technique, familiar from “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grand Jatte,” from 70 years before. There, tiny individual spots of color mix in the viewer’s eye to create the image.

A wall label reveals that she was struck by what that meant: Seurat’s revolution was less about specifics in the optical science of colors mixing on the retina, although that was important too, than it was about the painting acknowledging the presence of a viewer looking at it. After all, it’s your “responsive eye” that the artist is engaging.

You enter the equation, not as a gawker manipulated by the artist but as a participant in the artistic adventure. A generosity of spirit emerges, which is not how one ordinarily thinks of earlier 20th century abstract art.

At the Hammer, the installation has repurposed the design of the museum’s new Grunwald Center drawing gallery commissioned for the recent exhibition of Picasso cut-paper works — a room within a room. The division works well. The inner gallery features the representational drawings; the outer walls are lined with the abstractions. The earliest geometric abstractions are black-and-white — syncopated intersections of circles and squares; checkerboards seeming to collapse in on themselves, or to shape-shift into grids formed of disks; sharp zigzags that miraculously swirl or sinuously snake; lozenges that bend in space and more. Riley began them in 1960, moving into color by 1964.

The earlier date is worth highlighting. Essays in the generally fine catalog are good at articulating the period’s quickly changing history, as the inchoate forces that would coalesce into Pop, Minimal, Conceptual and other art movements began to gather. But one significant event is surprisingly left out. “West Coast Hard-Edge,” the first exhibition of postwar Los Angeles abstraction to travel internationally, opened at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art in March 1960.

Retitled from its California debut the year before as “Four Abstract Classicists,” the show featured the perceptually radical abstract paintings of John McLaughlin, Frederick Hammersley, Lorser Feitelson and Karl Benjamin. I don’t know whether Riley saw it — the ICA, then in Picadilly, was just a few minutes’ walk from the Royal Academy of Arts, where Riley also studied — but the visual resonance between her work and the four L.A.-based artists’ linear, geometric, hard-edge color abstractions is pretty obvious. Both explore the fundamental nature of perception.

It’s at least as clear as the importance of geometric color abstractions by Ellsworth Kelly, then being widely shown in London. That relationship has long been noted, but a possible Southern California connection doesn’t seem to have been. David Sylvester, the influential critic at Britain’s New Statesman, declared in his enthusiastic review of her first solo gallery exhibition in 1962, “Bridget Riley is a hard-edge abstractionist.” Sylvester’s friend and colleague Lawrence Alloway was the ICA’s assistant director. The term “hard-edge,” coined for the ICA show by its curator, L.A. critic Jules Langsner, was not yet in common use, so it’s a surprise to see it turn up published in the first significant Riley review.

Perhaps it was Sylvester, not Riley, drawing a link, or perhaps it was simple coincidence. That’s a question worthy of further examination, but for now “Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio” is a show not to miss. It was organized by Cynthia Burlingham, Hammer deputy director of curatorial affairs, with colleagues at the Art Institute of Chicago (home of Seurat’s “Grand Jatte”), where it had its debut in September, and New York’s Morgan Library, where it travels in June. All but a handful of the works were lent by the artist, as the title implies, which can sometimes mean they were of special significance to her.

'Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist's Studio'

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd,, Westwood

When: 11 a.m.–6 p.m. Tuesday–Sunday. Through May 28.

Contact: (310) 443-7000, hammer.ucla.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.