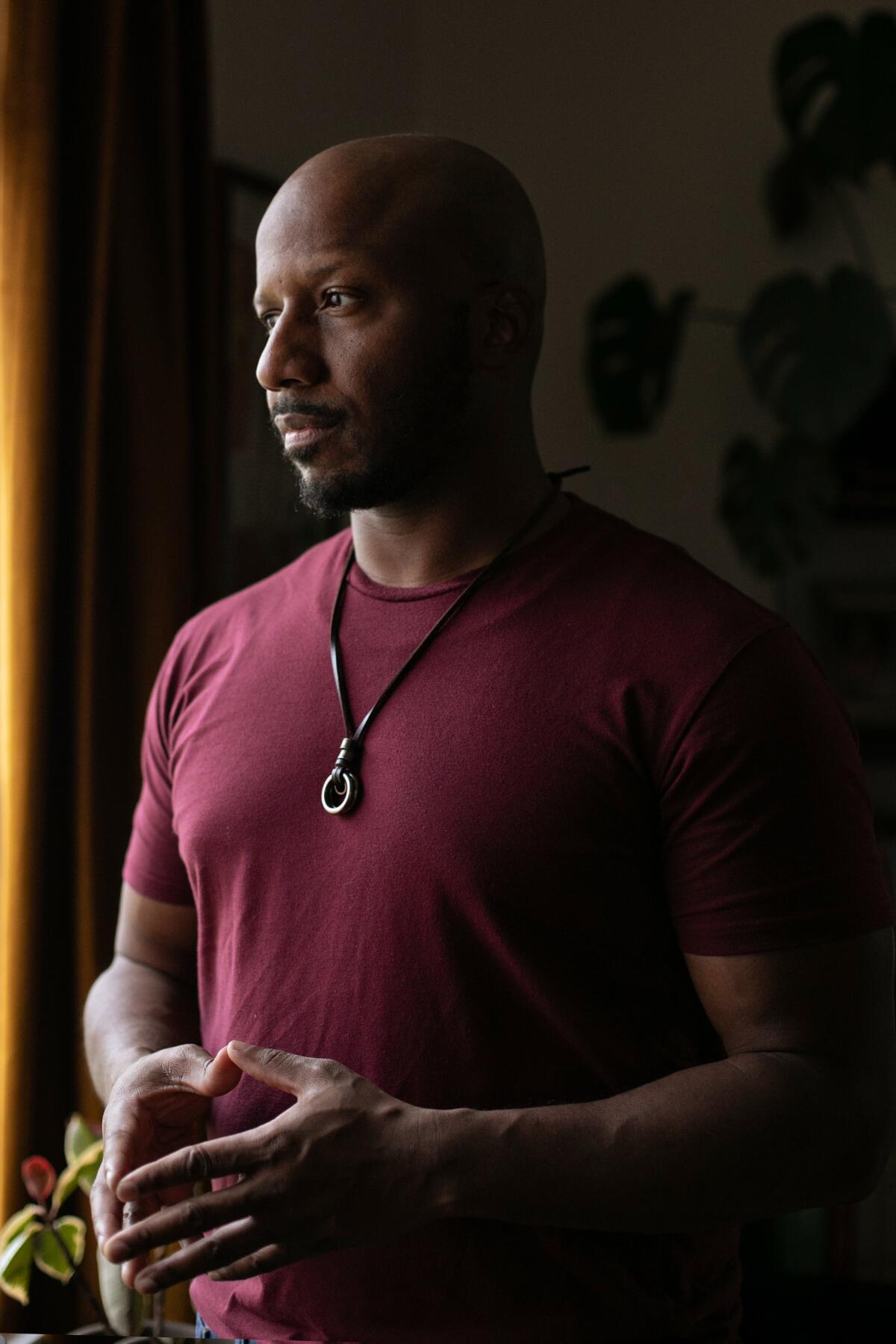

A former corrections officer’s winding journey to the stage: ‘No pathway for young Black artists’

Lee Edward Colston II called his friend and artistic collaborator Malika Oyetimein at 2 a.m. one day with the semblance of a story. Over the phone, he pieced together a massive idea for a play.

“Being a good friend she listened,” Colston recalls. “And then she said, ‘Lee, it’s 2 in the morning. It’s 2 in the morning and this sounds brilliant. Let’s talk about it in the morning.’”

That idea became “The First Deep Breath,” opening Thursday at the Geffen Playhouse in Westwood. It follows Pastor Albert Jones, whose eldest son, Abdul-Malik, returns home from prison while the family prepares for a memorial service on the sixth anniversary of their daughter Diane’s death. Abdul-Malik’s homecoming, coupled with the grief surrounding Diane’s passing, uproots the household’s unspoken truths.

About 10 years in the making, the play’s origins reflect Colston’s journey to the stage. While his love for theater began early in life, he took a detour to work as a corrections officer before studying drama at Juilliard. And through it all, the aching for a story he could call his own lingered, resulting in an epic, political family drama centered on Black voices. Now, his story is making its West Coast debut.

“‘The First Deep Breath’ was born out of not seeing what I hoped to see as a young Black artist,” he says.

Colston was a teenager when he saw a play for the first time. A mentor took him to a production of “For Colored Girls” in downtown Philadelphia, even though he showed no interest in sitting through a show.

“I watched this production in my hoodie and my Timberlands with my arms crossed, but by the story’s end, something changed in me,” he says.

In a show written by and starring Black women, he saw his mom, grandmother, sisters and aunts. “That production kicked me in my chest, and I knew in the back of that theater, ‘Oh God, I know what I want to do with the rest of my life,’” he recalls.

He trained as a martial artist and had ambitions of going pro, but after graduating from the Community College of Philadelphia, he dreamed of a career in theater. His dad, a former corrections officer, had other plans for him: following in his footsteps

Colston thinks the pressure stemmed from his father’s fear that a future in the arts could not be as stable. Working in a state prison would guarantee a steady income. Colston went through with his dad’s wishes.

He took a psychological evaluation, as required to become a corrections officer. In a cadet class of 30 to 40 people, Colston says his evaluation was the only one flagged. When the doctor learned of Colston’s aspirations to be in theater, it clicked. The psychologist informed him that he could succeed as a corrections officer, but that he’d be miserable and advised him to follow his dreams of being an actor.

“I didn’t listen to him,” he says. “I was afraid of disappointing my father, so I did the job.”

The psychologist’s words ended up being prescient. But Colston believes “that if I hadn’t worked there, I wouldn’t have become the playwright that I am today,” he says. “I really discovered writing on a cellblock.”

Colston started writing poems in his downtime. One became 10 and 10 became hundreds. The poems soon developed into his first play, “Solitary.” Even while working a job he didn’t feel passionate about, he continually found his way to the arts. Some of his biggest supporters came from the men in his unit who wanted to see him succeed as an artist.

“There wasn’t really a pathway that had been written for young Black artists to model themselves after, at least one that was visible to me in my community,” he says. “And these incarcerated men were like, ‘Yo, you gotta get out of here. You’re not supposed to be here. You’re meant for bigger.’”

He adds, “I just know in my bones this is not what I’m meant to do.”

While working as a corrections officer, he accidentally smashed his hand on a mechanical door in 2005 and went on disability leave. During recovery, he made a quiet promise he wasn’t going to work a regular job again. But first, he had to convince his father.

“I asked him, ‘Did you make sacrifices so that I could do the same as you, or did you make those sacrifices so that I could do better than you?’” Colston says. “‘And if you made those sacrifices so that I can do better than you as your son, then you got to let me do better.’”

He went on to graduate from the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, tour with “The Color Purple” and perform in “Othello” for the North Carolina Shakespeare Festival. Still, he craved more. More significantly, he realized there was more to learn. He had his eyes on Juilliard, but had already applied three times — twice for acting and once for playwriting. Oyetimein pushed him to apply a fourth time, even though he was hesitant. He got in as part of the inaugural cohort for the master of fine arts in drama and graduated in 2016.

By then, his parents finally understood what opportunities were available for him as an artist. Colston recalls his dad pulling him aside one day to say, “Son, I couldn’t have been more wrong. I didn’t realize how small my dreams for you were, and I’m glad you didn’t listen to me.”

Colston eventually left New York City and moved back home to write and focus on things that gave him joy. While he worked on Lynn Nottage’s “Intimate Apparel” with Shakespeare & Company in Massachusetts, he rehearsed during the day and wrote at night until 4 or 5 a.m.

Through writing, he processed the complex feelings and events within his family and slowly crafted “The First Deep Breath.” The story originated from a newspaper article he read about a family conflict that turned fatal. He says the artist in him started to ask questions like, “How did they get there?” From there, he started to “reverse engineer.”

“I knew that I had something special in my hands, but I didn’t think anybody would actually want to read it, let alone produce it,” Colston says. “It was really something that I have written for me to heal myself and to help me forgive my parents, to help me to forgive myself, to love myself in a deeper and richer and healthier way.”

He workshopped the play at National Black Theatre through their “I Am Soul” playwriting residency, and the show had its world premiere in 2019 at Victory Gardens in Chicago.

As the show makes its West Coast debut, Colston hopes the story he describes as “a political play disguised as a family drama” will allow audiences to learn radical empathy, starting from within the family.

“If we’re not able to offer that to one another inside of our own homes with our own families, how are we going to be able to find our way to each other in an American climate that thrives off division?” he says. “This play is me throwing my hat in the ring as a way for us to find our way back to each other’s life.”

'The First Deep Breath'

Where: Geffen Playhouse’s Gil Cates Theater, 10886 Le Conte Ave., Los Angeles, Calif.

When: 1 p.m. and 7 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays, 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Friday. Ends March 5.

Tickets: $30 to $129

Info: geffenplayhouse.org

Running time: 3 hours and 45 minutes, including two intermissions.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.