Walter Ulloa, media mogul and prolific art collector who elevated Latino communities, dies at 74

Growing up in Brawley, Calif., in the ’50s and ’60s — then a farmland sprawl of alfalfa, sugar beet, lettuce and sweet corn crops — Walter Francis Ulloa was an athletic kid. He rode horses, and as a teen won tennis tournaments throughout the Imperial Valley. But radio was his refuge. Ulloa loved rock ‘n’ roll and the blues, as well as the news, and he would listen whenever — and wherever — he could, holed up in his bedroom, cruising around in his car, stretched out in the backyard.

The radio was a revelation to Ulloa, a vehicle through which people could be heard.

“That was the first feeling of his wanting to raise his voice,” Ulloa’s wife of 40 years, Alexandra Seros, says.

Ulloa would go on to become a trailblazing force in media, giving voice throughout five decades to Latino communities across the U.S.

Ulloa passed away after sudden heart failure on Dec. 31. He’d been enjoying a quiet New Year’s Eve at home with his wife. He was 74 years old.

“There’s nobody like him,” Seros says. “He went from the early days of broadcasting to digital media, a different beast — it’s amazing what he accomplished starting with nothing but his mind.”

Ulloa was a newsman through and through, Seros says, waking at 5 a.m. daily to ingest a breakfast buffet of newspapers.

“For him, reading the morning paper was morning prayer — the Wall Street Journal, the L.A. Times, the New York Times, the Economist,” Seros says. “Papers stacked in the house, everywhere. I’d have to sneak around and throw them out. He was a curious guy, he wanted to know everything.”

Ulloa’s parents — Walter G. Ulloa, the first Mexican American certified public accountant in California according to Seros, and Margaret (Vasquez) Ulloa — encouraged his education. After attending USC as a business major and Loyola Law School, Ulloa worked briefly for the L.A. district attorney’s office before taking a job in the early 1970s at the city‘s Summer Youth Employment Program, which placed high school students from underserved communities as interns at Latino organizations. He went on to work at Los Angeles’ KMEX-TV in the mid-1970s, writing news commentary for Danny Villanueva (a.k.a. “Mr. V,” as Ulloa called him) and eventually rising to news director there.

Ulloa, who was Mexican American, long felt Latinos were underrepresented in the media. Partly fueled by that inequity, he co-founded Entravision Communications in 1996, buying a single Spanish-language TV station in the Coachella Valley and turning it into a national network of more than 100 TV and radio stations. Entravision Communications Corp., of which he was chairman and CEO, is now the biggest independent operator of affiliates of Univision, itself an American Spanish-language television network owned by TelevisaUnivision. Entravision went public in 2000 and is now a leading global media and digital marketing business.

As he was growing Entravision, Ulloa became particularly interested in acquiring “border stations” in border towns, because he grew up not far from the border of Mexicali, Mexico, Seros says.

“They reminded him of where he came from,” she says. “He felt like he knew them, and that these people needed to be mirrored.”

Together, Ulloa and Seros were an entertainment power couple. Seros is a longtime screenwriter who recently earned her doctorate from UCLA in cinema media studies; she wrote “The Specialist,” starring actors Sharon Stone and Sylvester Stallone, and co-wrote “Point of No Return,” starring Bridget Fonda and Gabriel Byrne. Ulloa was always supportive of her career.

But beyond media moguldom — and perhaps even more important to him — Ulloa was a fierce champion of Latinx culture. He served on the boards of the Latino Theater Company and LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, as well as the Music Center and LA84 Foundation. He was appointed to the board of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. by President Obama in 2013. In 2014, he and his two younger brothers, Roland and Ronald Ulloa, created a Latino endowment at USC in their father’s name.

Ulloa’s dedication to his heritage, however, was most prominently expressed in art. He was a prolific collector of Chicano and Mexican artists. Art collecting was something he and Seros bonded over, a pastime they enjoyed together. They scoured galleries on the weekends and on vacation, particularly in Mexico City, a destination they traveled to multiple times — they were married in a small church in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, in 1982 and had a son in 1992.

Their very first art purchase was a Javier Arévalo painting, in Mexico City, for $330 — framed; the second was a work by Vladimir Cora, purchased in Palm Springs and paid off in monthly installments.

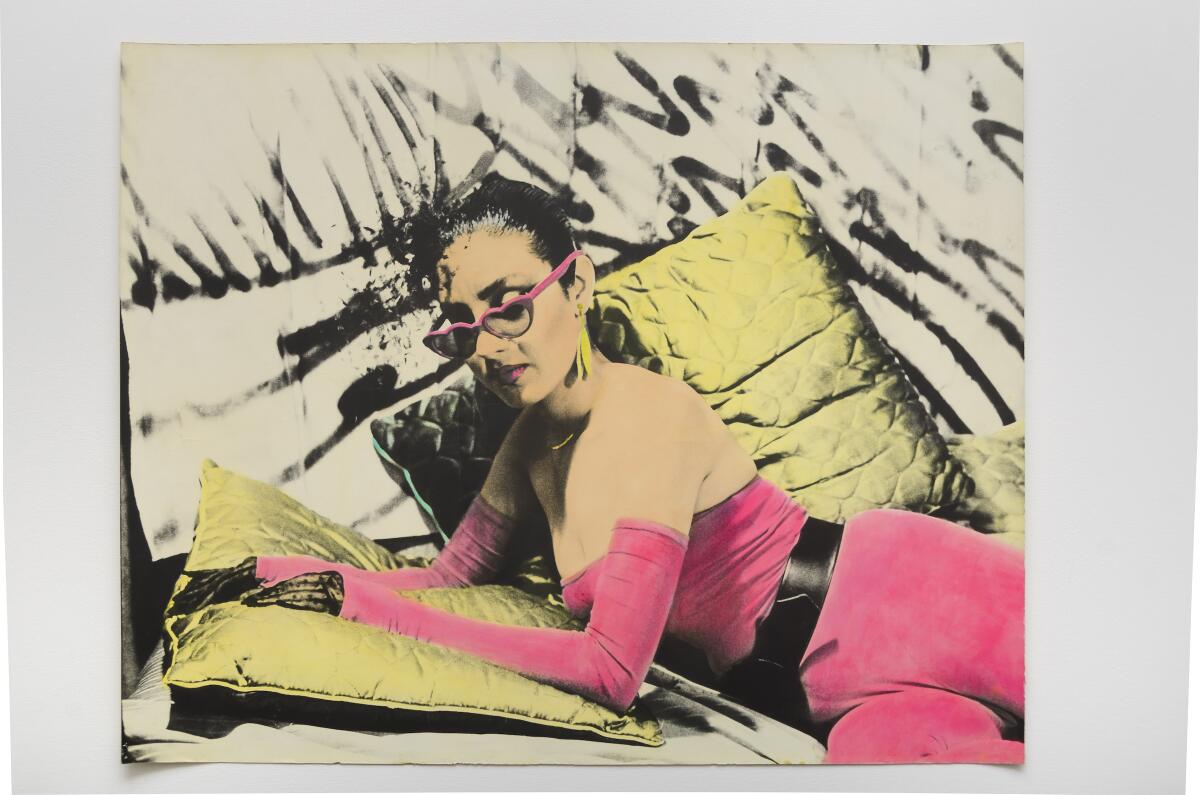

Art by the likes of Gronk, Patssi Valdez, Carlos Mérida, John Valadez, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Vincent Valdez, Francisco Toledo, Graciela Iturbide, Francisco Corzas, Camille Rose Garcia and others now hang on the walls of their 1930s Italian-Mediterranean style home in the Pacific Palisades. Other works, including an enormous George Yepes painting, filled Ulloa’s Santa Monica office. Additional works are tucked away in storage.

Art collector and actor-comedian Cheech Marin helped foster Ulloa’s interest in collecting Chicano artists.

“He focused us — ‘Have you heard of Carlos Almaraz?’ ‘Have you heard of John Valadez?’” Seros says. “We’d go to his house in the Palisades for dinner, and before that in Malibu and he’d show us his art and talk about it.”

Ulloa and Seros were donors to the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture (or “the Cheech,” as it’s referred to), which opened at the Riverside Art Museum last year.

“I was the only one out there at the time collecting Chicano artists on a large level,” Marin says of the early ’80s. “I was asking dealers, ‘Is there anyone else collecting?’ One of them said, ‘There’s this one guy — he’s the head of Entravision.’ So I made it my business to meet him. I showed him what I was doing, and he became a big champion.”

Marin says that Ulloa’s patronage helped elevate Chicano artists in the eyes of dealers. “He was instrumental in showing galleries it was viable by buying their art — the only language they really understood,” Marin says.

José Luis Valenzuela, artistic director of L.A.’s long-running Latino Theater Company, says Ulloa was an “essential voice” on the board and a close friend. Ulloa served on the board for about 20 years, offering guidance, vetting issues and supporting fundraisers by connecting the theater with artists for auctions or by buying artworks at events. He was also a lead donor to the theater company’s annual holiday production, “La Virgen de Guadalupe,” held downtown at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels with about 100 cast members.

“He was one of the big donors for that production every year,” Valenzuela says. “It was a consistent amount he gave and made the show possible every year — our gift to the community.”

Ulloa’s level of dedication to the board was unique, Valenzuela says. He was a supremely busy man, running a global media conglomerate, but he still found time to attend board meetings in person. Whenever he couldn’t, he always sent someone to represent him there and debrief him afterward. “He was just very interested in the community and very interested in the arts. Totally committed.”

Ulloa’s son, Bruno Seros-Ulloa, 30, shares his father’s work ethic. A clothing designer, Seros-Ulloa is now president of one of his father’s stations, LATV, which he’s retooled as a mostly English-language station aimed at millennials. Seros-Ulloa credits his father for nurturing his business savvy.

In the last few years, Seros-Ulloa and his father had become especially close.

“When I was younger, I thought we were so different; as I got older, I realized how similar we were in terms of our tenacity and passion and expressing our Latino heritage,” Seros-Ulloa says. “I watched in the wings how he operated his business. He instilled a confidence in me that I didn’t even know I had until it actualized into the leadership of LATV. He subtly and quietly gave me the strength to be the man I am today, not only in my career but as someone who can walk confidently in the world.”

Ulloa’s career had great breadth and impact. But Seros describes him professionally as a quiet, humble and caring leader. He didn’t seek the spotlight or like talking about himself, she says, preferring instead to ask questions of those around him. He was upbeat and gave generously through his philanthropy, often anonymously.

Seros says his professional mantra was, “We as Latinos need to see ourselves reflected in the media, and we have the demographics, the numbers, in the U.S. to do it.”

Ulloa loved to travel — it fed his curiosity — and he loved boating and port towns. The sea calmed him.

“He loved sailing into a new port, loved the daily rituals of people, watching them — families together, the dog, kids playing,” says Seros.

Ulloa was a champion of Los Angeles, his home of more than 55 years, of all Latinos and most of all, of Chicano and Mexican artists.

“There’s still this bias towards Chicano art,” Seros says. “Like, why aren’t more Chicano artists at the Whitney? And Walter felt it. He didn’t have a chip on his shoulder, but he wanted to break through it.”

Ulloa is survived by his wife, Alexandra Seros, son Bruno Seros-Ulloa, brothers Roland and Ronald, sister-in-law Soo-Bin, nephews Luis and Anthony and niece Madeline.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.