For artist Uta Barth, learning to photograph is a way of learning to see

Uta Barth is a photographer, and her chosen tool, the camera, is integral to the making and understanding of her work. But when asked about art that has had the greatest impact on her, she says, “I rarely think of photography. I think of sculpture and installation and painting. I don’t categorize media the way the world likes to.”

Her freedom from party-line thinking becomes palpably clear when you enter her retrospective exhibition now at the Getty, an extensive show spanning from Barth’s college days to the present. The photography galleries don’t look like they typically do. Pictures hang at different heights and at irregular intervals. Explanatory wall text is kept to a minimum and sequestered to one section of each room. Title information is concentrated there as well, apart from the images, rather than beneath or beside them.

“I consider the framing and mounting and display of the work to be a continuation of the work itself,” Barth says. “I look at the gallery space as a sculptural problem to solve. The space between pieces matters as much as the pieces themselves. Artwork, architecture and light — I want to give equal strength to all of those elements. From the beginning, I had to tell everyone [at the museum] this is not a collection of pictures. It’s an installation.”

Imagine you’re taking a picture of a friend.

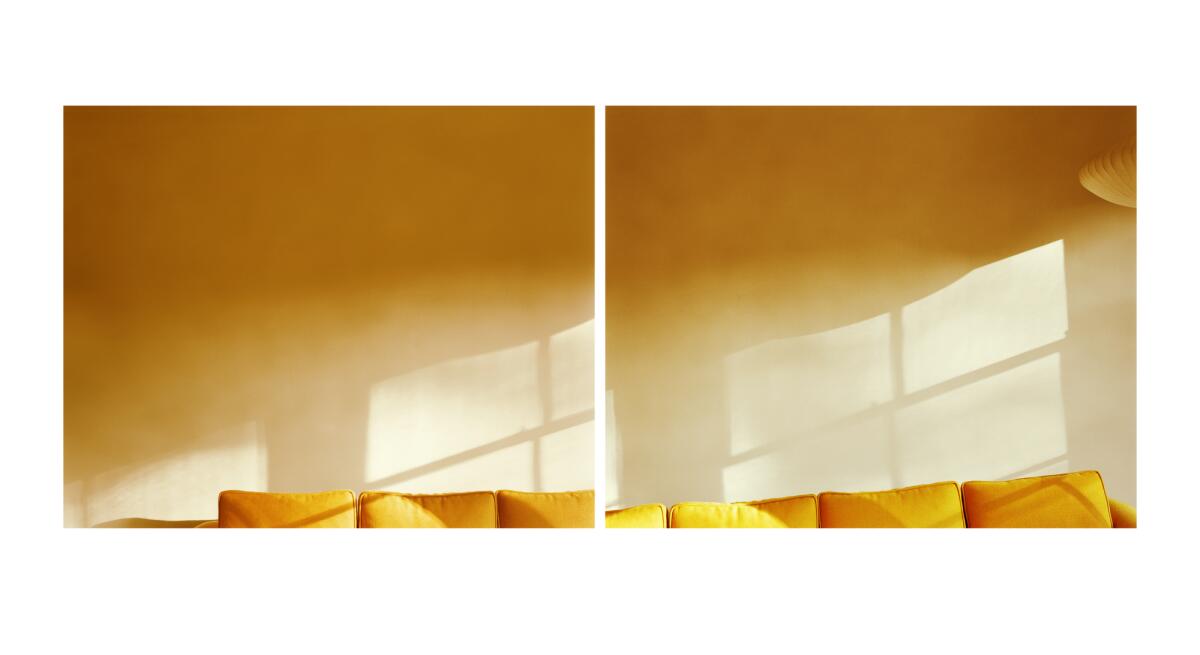

There are images in “Uta Barth: Peripheral Vision” of curtain hems limned in light, a lamp hanging in otherwise empty space, the edge of a window frame, a horizon line of sofa cushions, distant trees. But an inventory of recognizable motifs in the pictures hardly suffices to account for either how the show looks or how it feels. It is an environment, an experience. Quiet, yet assertive, it demands stillness, contemplation, patience.

“One of the reasons I was interested in doing this show was because of the slow pace of the work,” says the Getty’s assistant curator of photographs, Arpad Kovacs. “The longer you look, the richer the experience of looking becomes. In general, we forget the pleasure of looking, because we’re searching for a subject, the reason something is on view. Once we grab that, we move on. Her work doesn’t operate that way.”

The photographs in “Ground,” for instance — the mid-1990s series that first earned Barth wide attention, through its inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art‘s New Photography exhibition and a solo presentation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles — whisper of place, but are conspicuously silent on persons or plot. The domestic setting, Barth’s own home, is distilled to a discontinuous sequence of long blinks: a light-drenched wall, a corner, the edge of a chest of drawers, a full bookcase.

Barth unsettles the figure/ground relationship by assuming but omitting a clearly focused figure. What remains, and what Barth champions as plenty, is the ground. What conventionally would register as secondary becomes primary; the peripheral becomes all. These pictures aren’t out of focus, she has explained now for decades; rather, they are focused on the point unoccupied by that absent figure.

The L.A.-based artist, 64, recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and a Guggenheim Fellowship, among a slate of other high honors, attended UC Davis as an undergraduate. Photographer Lewis Baltz was there teaching a graduate seminar, and she talked her way in. His impeccably deliberate sense of composition became a mainstay in her own work, and further, “he opened the floodgates for me, making it natural to consider other media and to think outside of the photography world.”

The ‘80s were a heady time in arts education, and by the time Barth received her master of fine arts from UCLA in 1985, her foundation in conceptualism and postmodern theory ran deep.

“There was a lot of dismantling and rethinking the politics of representation,” she recalls. Some of her early work, included in the show, interrogated and interrupted the gaze. She made self-portraits, for example, in which her form was obscured by a dark square or shadow. She soon felt, however, that she’d exhausted that avenue. “I didn’t want to make work that was didactic.”

The sculptor Charles Ray had just started teaching at UCLA when Barth entered the program, and he was among several young faculty members that she befriended. The conversations between them were formative in her development of a practice centered around how the senses operate, not just the mind.

“Charlie took me aside at one point,” she recounts, “and talked to me about trying to make something that’s not just a cognitive experience but that hits you on a visceral level, that’s not just about decoding signifiers.”

Ray’s instigation dovetailed with considerations of space and perception that Barth had just read about in Lawrence Weschler’s then-new book about artist Robert Irwin, “Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees.”

“Irwin made perfect sense to me. He made this radical move — instead of depicting light, like painting and sculpture and photography do — to paint or sculpt with light, the way one would use any other medium. That’s conceptually a huge step, to take a room and bathe it in yellow light and decide that’s an artwork.”

MacArthur 2012 fellows include Uta Barth, Chris Thile

Though Barth never had any formal interaction with him, “she has been a lifelong student of Irwin’s,” Kovacs says. Irwin, whose design for the Getty garden has been an evolving experiment in light, color and texture, was never far from Barth’s mind as she worked on a 2018 commission to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the opening of the Getty Center. The wraparound installation of panel-mounted photographs — and one very slow-moving video that presents as a still picture — constitutes the most recent work in the current show.

For the project, titled “...from dawn to dusk,” Barth identified a relatively nondescript side entrance to one of the Richard Meier-designed Getty buildings, the Harold M. Williams Auditorium, and chronicled the site’s changing face, through a year’s changing light and weather. She made 64,000 images, treating the wall as a kind of modular blank canvas for time and atmosphere to draw itself upon.

“In the process of working on this commission,” she says, “I began to understand the garden more and more. Everything done in that garden seems designed to counter the architecture — countering the grid with the circle, the lack of color with color. All of it is the exact opposite of the architecture, which is very controlled and rigid. I wasn’t eager to counter the architecture in the way Irwin had. I wanted to find a way of referencing it, but deconstructing it.”

Barth ultimately “embraced the grid” and used it as the organizing basis of her highly deliberate sequence of images that vary in size, scope of view, degree of focus, and intensity or diffusion of color. The work’s marriage of ephemerality and materiality is a defining characteristic of Barth’s approach over the past three decades, and among many aspects of her practice that have influenced a younger generation of artists.

Photographer Amir Zaki, a student during Barth’s long tenure at UC Riverside (1990 to 2008), and later her teaching colleague there, notes, “Something very important I took from Uta was an emphasis on the photograph as an object, not ‘merely’ an image. I’ve always admired that about her work and presentation, and it’s something I consider in my work quite a bit.”

Zaki photographs the found and built environment, digitally stitching together images to trouble the boundary between natural and unnatural, and to conjure a sense of duration. Barth too is deeply interested in expanding the photograph’s temporal moment, something she evokes through the use of sequenced images.

Barth was a thoughtful teacher, Zaki recalls, but she was also tough. “She had a way of playing good cop and bad cop at the same time. She was very nurturing and encouraging, but she didn’t hold back on telling you what you didn’t want to hear, especially about editing.”

Zaki also worked for Barth for many years as a printer, and that too proved enlightening. “We were printing things that were very subtle. I learned how particular a person could be. I learned a sensibility — that we could tweak things in minute degrees and it means something. It actually changes the whole thing.”

The ripple effect of Barth’s role as mentor and professor — at UC Riverside, and as visiting faculty at ArtCenter College of Design (2000 to 2012) and UCLA (2012 to present) — has been consequential, and ongoing.

“The thing about great teachers,” says Paul Mpagi Sepuya, who studied with Barth at UCLA, “is that you keep their questions with you, and ask them of yourself so you don’t feel stuck.”

Sepuya complicates the studio-based portrait genre in his constructed scenes of male bodies (including his own) posing, entwining and looking through the camera, itself an instrumental character, with a sort of agency. Tutorials with Barth during his first year of grad school helped him crystallize his methods, pare things down and refine the work he was then making using multiple image fragments and mirrors.

Reviewing his notes from her 2015 winter-quarter studio visits, Sepuya recites the questions Barth asked of him: “With all of this information, how is a viewer supposed to make sense of things? How do they know what’s significant? How do they find their way through?”

Sepuya uses Barth’s work in his own teaching, at UC San Diego, to help his students “get away from the preconceived idea of what a good picture is. When I’m talking about focus and depth of field, we look at her work to see that it’s a choice. And when we talk about vision and perception, it’s not about what you’re looking at but how you’re looking.”

From her earliest years as an artist, Barth’s attention has been drawn to the eye’s behavior: what attracts it, what makes it stay, what causes it to double back, what generates after-images and optical fatigue. Learning to photograph was, for her, a way of learning to see.

“When you first start walking around with a camera, you start to become aware of the edge. Human vision has no frame around it. Camera vision superimposes a frame around whatever you’re looking at. It’s a composed kind of vision.

“You realize that you don’t have to go out and find some kind of spectacular subject matter. You can look at cracks in the ground and make an interesting composition out of that.”

Nearly all of the photographs in the Getty exhibition (aside from the commission) were made inside her own house, observing what normally goes unnoticed. She can be completely engaged for hours, sitting in a room and staring at a wall, she says. Her work over the years serves as something of a steady, stealthy prompt for increasing our own capacity to do the same.

“To photograph in my home is a matter of convenience,” she explains, “but it’s a way of saying that vision happens everywhere. Working with what’s around me all the time is to drive home that point and to get people to think about what is around them all the time, what is in the immediate environment. “

"Uta Barth: Peripheral Vision"

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles.

When: Tuesday–Friday and Sundays 10am–5:30pm, Saturdays 10am–8pm. Closed Mondays. Through Feb. 19, 2023.

Info: https://www.getty.edu/visit/center/

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.