Animation by Erik Carter / For The Times; video by Steevy Areeco, Jennifer Bryant and Angela Sharbino

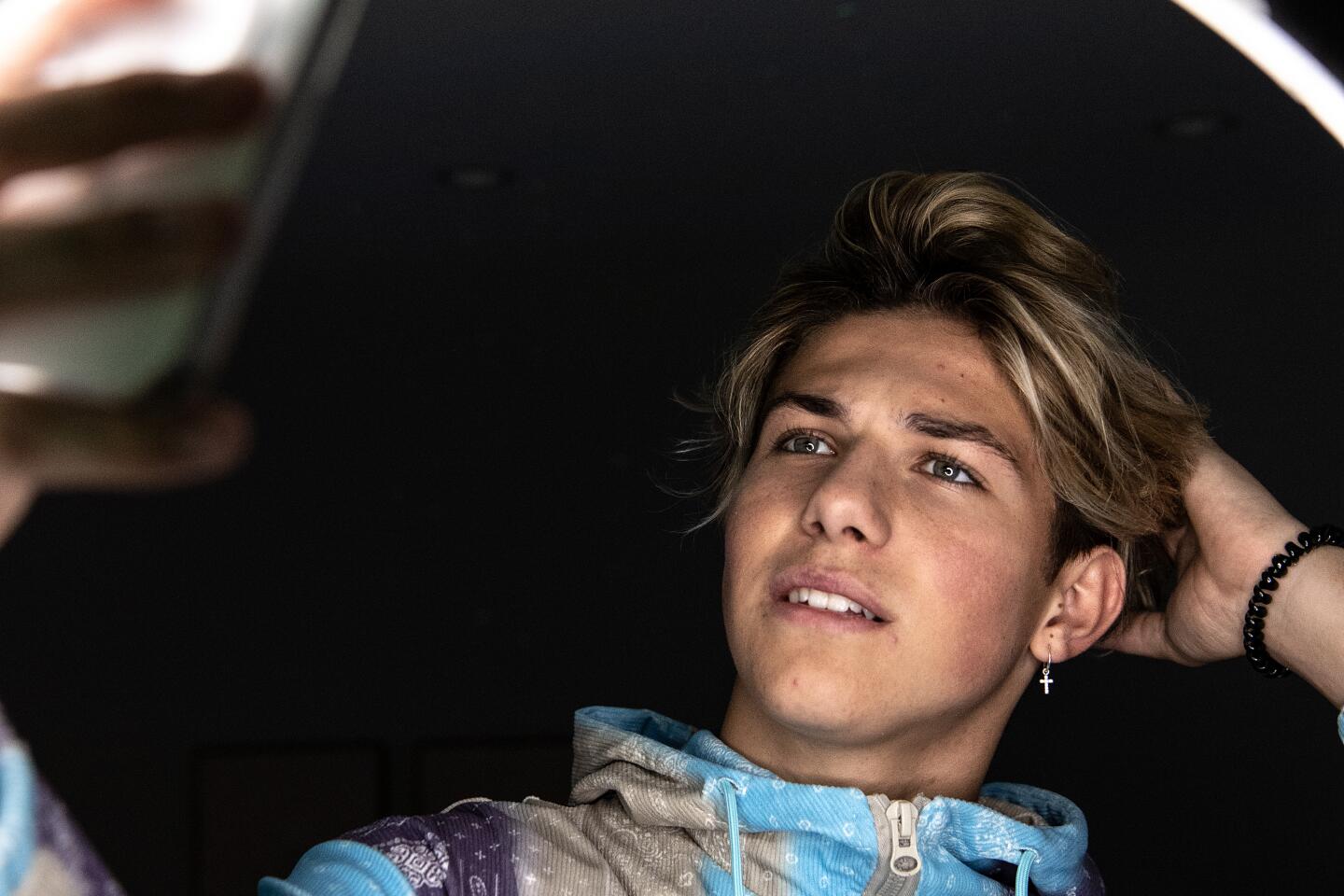

Piper Rockelle looks like the kind of girl who’d offer you a seat at her table in the cafeteria. Cute and approachable, with an easy smile. More Fashion Nova than Gucci. IG filled with kittens and her boyfriend.

Her ability to be at once aspirational and relatable has helped attract 10 million subscribers to her YouTube channel, where the 15-year-old social media star has earned up to $625,000 a month sharing carefully curated snippets of her neon-colored world. Sometimes she sings or dances — she’s good but not intimidatingly so. Mostly her fans come for the soapy reality-show fun she has with her friends.

Their group, called the Squad, lip-syncs to bubblegum pop music and documents their pranks (Piper pretends she has amnesia!), challenges (becoming a mom for the day!) and crushes (last to stop kissing boyfriend wins $10,000!). In Piper’s universe, there aren’t any final exams or broken hearts that can’t be fixed with a hug or a trip to the Candy Factory.

For subscribers only

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

That was the case, at least, until January, when a bombshell lawsuit alleged that Piper’s life is more “Mommie Dearest” than Mouseketeer. In the suit, 11 former Squad members, including two of her cousins, claimed they were “frequently subjected to an emotionally, physically and sometimes sexually abusive environment perpetrated” by Piper’s mom, Tiffany R. Smith, on and off set during time spent with her company Piper Rockelle Inc. Smith denies the allegations.

The lawsuit offers an unsettling glimpse into a largely unregulated world of social media, where children spend long hours cranking out videos and branded content. Kids can make millions of dollars and become online celebrities, but because the content is made in the privacy of their own homes, child labor laws — which do apply to social media influencers — are not consistently enforced.

A Times investigation found that Smith, 41, operated a multimillion-dollar company that did not pay the children who filmed popular videos with her daughter, and that the children worked long hours without scheduled breaks for rest or meals and were not provided with regular on-set education, according to a review of dozens of court filings, emails, casting calls, talent releases and filming schedules, as well as interviews with the plaintiffs and their parents. Many of the parents have accused Smith of violating labor laws, and said she should have obtained permits and credentials that the state requires to work with minors.

“Imagine if these kids had been on a movie set for Lionsgate. People would go to jail if this had happened at a studio.”

— Matthew Sarelson, a lawyer for the plaintiffs

The claims of sexual misconduct, along with some of the other alleged behavior, have drawn scrutiny from the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department.

The plaintiffs say the allegations exemplify why child labor laws are so important to protect kid performers from exploitation by their employers or their guardians.

“Imagine if these kids had been on a movie set for Lionsgate,” said Matthew Sarelson, the lawyer for the plaintiffs. “People would go to jail if this had happened at a studio.”

Smith’s attorney, Kenneth Ingber, said the Squad’s work fell into “a gray area” of the law. Nonetheless, Smith says she did receive a permit to work with minors this year “to try to avoid controversy and to reflect our maturing and evolving business.”

Smith questions why she is being sued over an alleged lack of labor protections for minors who filmed at her house.

“I have always strived to comply with the laws and never considered myself an ‘employer’ when kids get together voluntarily to collaborate on making videos,” Smith said.

Smith questioned whether other parents had complied with labor laws on the videos their children made individually. For example, her attorney said, “Do all of these plaintiffs have a permit to employ minors while filming their own content?”

The answer is complicated: The parents said they abided by portions of the laws but alleged in the suit that Smith was ultimately responsible for maintaining a professional operation because she was acting as their children’s employer.

Piper seemed fragile during an interview, which she and her mother opted to conduct in their attorney’s office over Zoom this fall. The stark white walls behind the teenager provided a striking contrast to Piper’s usual onscreen backdrop: the glittering pool and expansive rooms of the $2.3-million mansion she bought from actress Bella Thorne in 2020.

Gone was the positivity that Piper has mastered as well as any seasoned Disney Channel vet. She was scared and hurt. And she wanted to make something very clear: The plaintiffs in this lawsuit are out to get her, and no matter what they may say, they’re not doing it for her own good.

“These people, they don’t love me,” she said, under the office’s fluorescent lights. “Because if they did love me, they wouldn’t be doing this.”

By “this,” she means threatening her family’s livelihood and reputation. Since the lawsuit was filed, YouTube has demonetized her channel, causing her to lose $300,000 to $500,000 a month, court records show. Venues have scrapped her live tour dates — curtailing another form of revenue she’s relied on since the end of 2019.

The Lawsuit

Seven former Squad members interviewed for this story are among the 11 plaintiffs, all of whom are minors, seeking at least $22 million in damages from Piper Rockelle Inc.

Their suit joins two others that were already wending their way through the courts. One was filed by Smith against former Squad parent Caroline Fratacci for defamation and emotional distress. In her response to the complaint, Fratacci claimed Smith had sexually assaulted a 17-year-old boy. In a separate suit, a mother named Johna Kay Ramirez, said Smith helped her son legally emancipate from her in order to stay in the Squad.

For the record:

6:04 p.m. Dec. 18, 2022An earlier version of this story said former Squad parent Caroline Fratacci sued Tiffany Smith. Smith sued Fratacci for defamation and emotional distress, and Fratacci filed a response to that lawsuit.

But it is the suit filed by 11 former members of the Squad that has placed the Piper Rockelle saga at the center of an explosive online controversy. The plaintiffs, all of whom are minors, allege in the lawsuit that Smith offered to show an 11-year-old girl how to perform oral sex, mailed Piper’s underwear to men and pretended to be a raunchy version of the family’s dead cat while inappropriately touching and harassing the children.

The former Squad members are seeking at least $22 million in damages, in large part because they claim that after leaving the group, PRI conspired to “tank” their channels by “engaging in a variety of dirty tactics” that caused them to lose money. The lawsuit remains in litigation, with no hearings scheduled until 2023.

All of the parties involved in the case have lucrative business interests at stake. PRI was making $4.2 million to $7.5 million in revenue annually from social media advertising alone, according to court records. The plaintiffs’ YouTube revenues were lower but still substantial. The highest earning kid in the lawsuit was averaging $28,000 in monthly revenue from his own channel; that dropped to $4,800 a month after the minor left the Squad.

The money earned by the plaintiffs came from advertisements placed on their YouTube channels — not from PRI. Most Squad members agreed to forgo financial compensation from Smith’s company, choosing instead to be “paid” with mentions of their social media handles in Piper’s videos. They hoped if their subscriber bases grew, money from brand deals would follow.

When filming at Smith’s home, the Squad would first shoot videos for Piper’s channel and then move on to creating content for their own YouTube pages that Piper appeared in. Smith points out that Piper did not receive money from the Squad members for her contributions to their videos.

Smith contends that the suit is nothing more than an act of professional jealousy by showbiz parents whose kids aren’t as successful as hers; the plaintiffs say they want to ensure that no other children have to endure what they saw as an abusive environment while making online content.

“This whole case is based on lies that are driven by financial jealousy,” said Smith. “Financial jealousy of a 15-year-old girl.”

The Times interviewed seven of the plaintiffs and their parents who collaborated with Piper on hundreds of videos between 2017 and 2021. All of them quit the Squad because of their concerns over the work environment.

Beginning in April 2020, numerous concerned parents contacted various public officials, according to a Times review of dozens of pieces of correspondence, documents, pictures and court records. Complaints were lodged with the FBI, the LAPD, the Department of Children and Family Services and the Division of Labor Standards Enforcement, each reporting Smith’s treatment of the minor children filming at her home.

The plaintiffs’ parents said they realized the seriousness of the alleged sexual misconduct during a pivotal meeting with attorneys in September 2021. At the time, the parents were discussing the legal options regarding what they said were Smith’s child-labor violations and the possible sabotaging of their children’s individual YouTube accounts.

“This whole case is based on lies that are driven by financial jealousy.”

— Tiffany R. Smith, mother of Piper Rockelle

During that conversation, darker claims began to emerge.

“And that’s when it became, ‘Me, too! Oh my gosh, me too.’ The kids literally couldn’t talk fast enough because they realized they all had the same stories,” said mother Ashley Rock Smith, noting that some parents began crying when hearing the allegations.

In July, Smith countersued the plaintiffs, alleging they engaged in a conspiracy to defame her, and ruin PRI; Smith voluntarily dismissed the lawsuit in October.

The Piper Rockelle content factory

Paparazzi don’t wait outside Piper’s fuchsia-painted mansion in the San Fernando Valley, but among a young, YouTube-fixated demographic, the ebullient brunette is idolized. As a rising star on the most-watched video-content platform of her generation, Piper bypassed the traditional paths of Nickelodeon and Disney to become a millionaire through the monetization of her social media content.

Propelled by the force of millions of likes and heart emojis, Piper was making between $4.2 million and $7.5 million a year before the Squad’s lawsuit. Her YouTube videos had amassed over 1.87 billion views, and companies such as NBCUniversal, Disney and Amazon were paying her to promote their products on Instagram and TikTok. Super-VIP tickets on her tour — a live variety show that trades on the Squad’s online personas — went for $599.99. She was also selling merchandise on her website, offering personalized greetings via Cameo and making music. She has released seven singles.

Still, by YouTube standards, she is “actually middle class, as crazy as that sounds,” said Eugene Lee, chief executive of ChannelMeter, a San Francisco-based creator management and payment platform.

Like many YouTube content empires, PRI was built at home. Before they bought Thorne’s house, Piper and her mother rented a 1920s house in the Hollywood Hills, living there with Smith’s boyfriend, Hunter Hill. Hill, 26, who is also a defendant in the Squad’s lawsuit, filmed and edited their videos. His voice is omnipresent in Piper’s output, a playful older brother type prompting the kids with questions or narrating their activities.

“Have you lost your brain?” he joked in one video with Piper when she exclaimed she was turning her house into a petting zoo by trucking in goats, chickens and bunnies. Another time, she imported snow to create a winter wonderland.

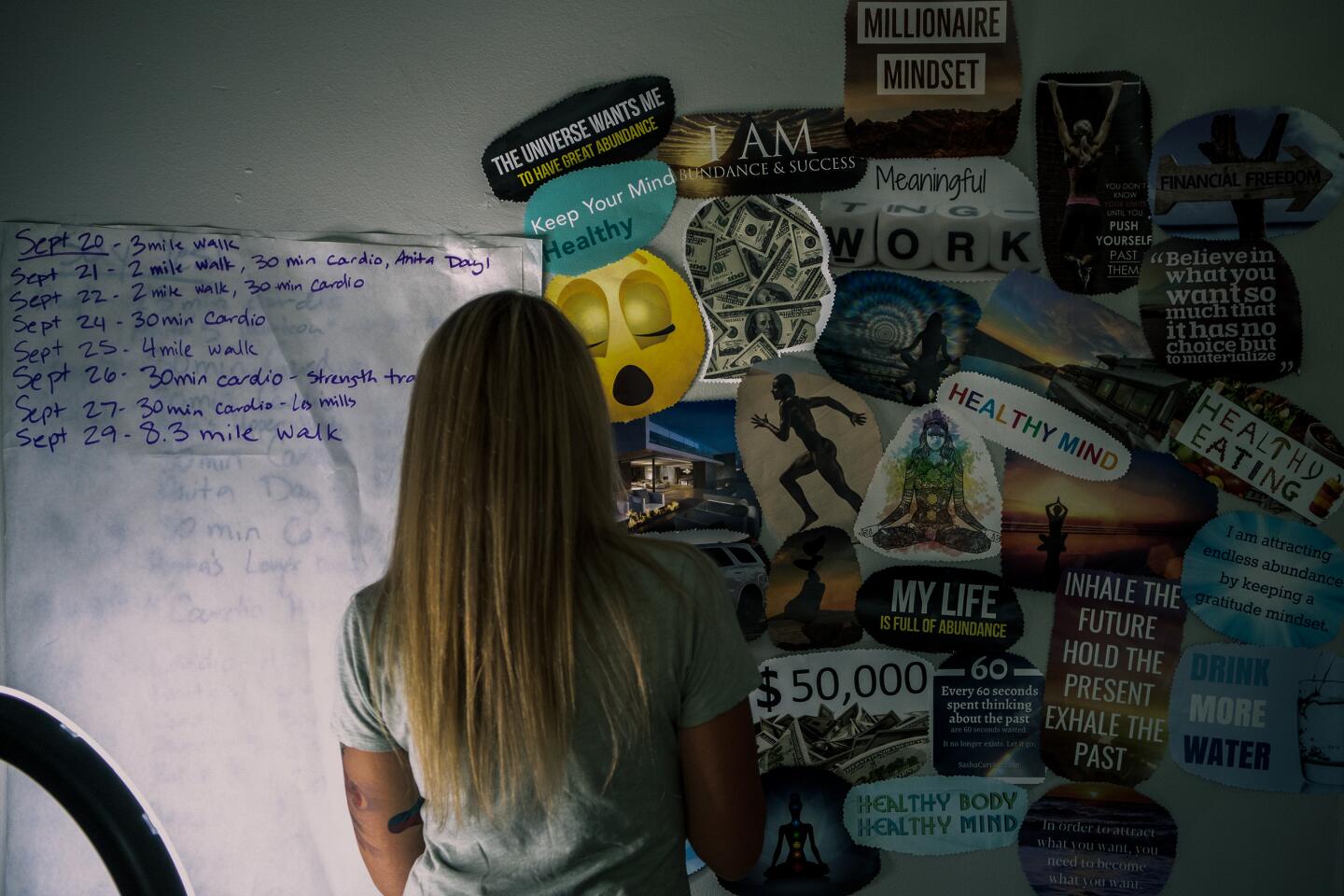

Parents said Smith spent her Sunday nights planning content for the week and was responsible for coming up with the creative vision for the videos. The kids didn’t necessarily learn lines, but Smith said she would sometimes suggest to them what to say. Smith said she didn’t devote any particular night to Piper’s content, and that each Squad member was responsible for coming up with their own ideas for their videos. “If they asked me for my feedback, I readily gave it to them,” she said.

Influencer economy

Some 86% of millennials and Gen Zers are willing to post branded content for money, and 12% consider themselves influencers already, according to a 2019 report by the market research firm Morning Consult.

Piper Rockelle was making $4.2 million to $7.5 million a year before the lawsuit.

The Times has reviewed rough schedules that were texted to Squad parents by Smith the night before shoots. In those messages, she relayed the hours their kids were needed and the titles of the videos set to film. In videos, the children can be seen doing ordinary kid things — jumping on the trampoline, hanging in the manicured backyard or doing fashion shows in the garage.

What ends up onscreen gives the appearance of laid-back fun. And Smith maintains she did not view her home as a workplace.

“There is tremendous uncertainty about what labor laws apply in the context of filming a YouTube video at home, with an iPhone,” said Smith’s lawyer, Ingber. “At what point is that a professional production?”

Ingber said he believes PRI has “done nothing wrong on the labor front,” noting that the company changed its policies to adhere to child labor laws because “the world is changing and, let’s face it, we’re in a lawsuit, so we’re going to be a little more careful.”

“That’s not to say that we were wrong not to have them three years ago,” he added. “That is highly, highly debatable.”

Sarelson, the lawyer for the plaintiffs, argues that PRI should be treated no differently than a traditional production company and hopes the lawsuit sparks change in the social media space. “I think that’s an important avenue where this — and other cases — are headed.”

In California, which has some of the strictest child performer regulations in the country, protections for children on sets include a maximum eight-hour workday, three hours per weekday of on-set school instruction and a state-licensed studio teacher/welfare worker present at all times during production. The state also mandates that adults employing children must obtain permits to do so, and that 100% of a child’s earnings belong to that child. (Smith says she did set aside Piper’s money.) A parent or guardian must also be within sight and hearing range of a minor at all times.

The Times found indications that PRI was operating as a professional production company. Hill said his videos were shot mostly on a professional Sony 7R camera. In 2019, an audition was posted on L.A. Casting, which was used to find kids to act with Piper for a show called “Hollywood Homeschool.” The part called for a 10- to 13-year-old to play an actor who’d moved to Hollywood “with his/her overbearing stage mom,” who is forced to “be the adult in their reversed Mother/Child relationship.” The child who was offered the part was asked to have their guardian sign off on a minor release stating that “Performer desires to appear in one or more videos” with Piper, who is referred to as “Artist” in the contract.

Between 2017 and 2021, Squad members filmed videos at Smith’s home for up to 12 hours per day, said five of the plaintiffs’ parents. They also said she regularly forbade other adults from being on set.

Smith said adults were welcome on set and that a guesthouse was available for them during filming. She added that making Piper’s videos took two to four hours, and that additional filming Squad members did after that was up to them. “Any other time that the kids spent was either socially or making videos that were uploaded on their own channels for their own profit,” she said.

According to several Squad parents, Smith briefly hired a set teacher named Jacquelyn Moen. The Times reviewed texts in which Moen was introduced to parents as a teacher, but she taught only a couple of sessions, parents said. Moen declined an interview request. Smith said Moen did not return because of the objections of a Squad parent.

Smith said she did not feel responsible for the education of the other kids in the Squad, noting that “their parents were each responsible for their schooling.”

None of the Squad kids attended traditional school; they completed their coursework through online programs. In March 2020, some parents tried to bolster their children’s education by hiring private charter tutor Lynda Reichbach. She set up in Smith’s guesthouse, working with two of the performers in private hourlong sessions.

But according to Reichbach, Smith was uninterested in the children’s education. The teacher recalled a day when she was mid-lesson and Smith barged into the room and began screaming at her. Reichbach said Smith instructed her pupil to report to set immediately — and she didn’t care whether the tutor’s hour wasn’t up. It was her house, Smith said in an expletive-laden rant, and she controlled what went on in it.

“You would have thought I was stealing something and I was a thief,” Reichbach said in an interview, adding that the confrontation left her in tears. “She caught me so off guard, because why would she treat me like this, or talk to me this way?“

Reichbach did not return. One mother, however, had the tutor continue to work with her child off-site.

Smith called the characterization of her interactions with Reichbach “incorrect” but did not elaborate.

“I’m like, ‘You have to put her in school, Tiffany. She has a right to an education.’”

— Patience Rock Smith, sister of Tiffany R. Smith

Squad members said they never saw Piper do schoolwork, and they claimed she had difficulty reading. Plaintiffs say Smith forbade others from talking about school or doing homework in front of Piper because it made her feel bad, and that Piper got help when she had to read any text in a video.

“She would have, like [her boyfriend] read it to her and then she’d say it in the videos,” said another former Squad member named Sawyer, who joined in February 2020 and stayed for roughly a year. Smith denied this, calling it “another mean-spirited personal attack on Piper.”

Piper’s aunt, Patience Rock Smith, recalled clashing with her sister Tiffany over Piper’s lack of schooling when the child was around 9, which Smith has disputed. “I’m like, ‘You have to put her in school, Tiffany,’” Patience said. “‘She has a right to an education.’”

Tiffany Smith said she was hurt that her sister would bring up Piper’s reading, and that Piper has been home-schooled all her life.

Piper added: “I am dyslexic, and it gets hard on me. It gets really hard. And that really upsets me. ... The claims that people are making — they’re very stupid.”

Home schools in California are required by law to file annual private school affidavits through the Department of Education. According to the Education Department, Smith filed two affidavits for a private school called Eastown, first for the 2017-18 school year and then for 2019-20. The Times did not find any filings for 2018-19 and 2021-22, according to department records, though Smith said she filed them.

Allegations of thwarted labor regulations are not uncommon in the fast-growing digital media sector. Influencer marketing investments are expected to grow to $5 billion in the next year, according to a 2022 report by marketing firm Traackr, and so-called kidfluencers are significant players in this thriving industry. According to a 2019 report by the market research firm Morning Consult, 86% of millennials and Gen Zers are willing to post branded content for money, and 12% consider themselves influencers already.

Although influencers may fall under the child labor laws established decades ago, it wasn’t clear how those laws covered the new digital sets. So four years ago, BizParentz Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for professional child performers, lobbied for a bill in California that would make it “crystal clear” that social media performers were not exempt from state rules.

“We had started to hear chatter amongst the influencers that these [laws] didn’t really apply to them because nobody was employing them really,” said BizParentz co-founder Anne Henry. “They were saying that they were just appearing as themselves, and that was somehow different. It’s not different.”

The legislation, Assembly Bill 2388 — known as the Child Performers’ Act — Social Media Influencers — became law in 2018 and required YouTubers to obtain entertainment work permits, among other mandatory protections. The new law also mandated that kidfluencers adhere to the Coogan Law, which was passed in 1939 and named after child actor Jackie Coogan, whose parents spent all his earnings before he reached adulthood. Employers must also put 15% of a child’s total earnings into a special trust.

Still, enforcement has been woefully inadequate, critics say, likening the situation to the early days of Hollywood when labor abuses were rampant.

YouTube spokesperson Jessica Gibby said in a statement that Piper’s channel had violated its Creator Responsibility policy by “engaging in off-platform behavior that harms the YouTube community.” As a result, YouTube “indefinitely suspended monetization,” when the creator collects 55% of revenue from ads featured on their page.

“In this case, Piper’s mother Tiffany Smith, who administers the earnings on this channel, is facing multiple allegations of child abuse and exploitation,” Gibby said. “We take these allegations seriously.”

The Department of Industrial Relations, the state agency responsible for enforcing workplace labor regulations, was slow to take action on the complaints it received about Smith. According to emails reviewed by The Times, Deputy Labor Commissioner Rick Mejia was notified of possible problems with PRI as early as April 2020, but two years later in an email to a Squad parent, Mejia said the investigation was “still in the beginning phase.”

The earliest letter sent to the Division of Labor Standards Enforcement by a parent — who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution from Smith — complained about a Squad shoot during the COVID-19 lockdown and alleged ongoing child labor violations. The correspondence stated that Smith failed to obtain a permit to employ minors, did not provide water and snack breaks, and didn’t employ a set teacher. It also said Smith did not pay the kids who worked for her multimillion-dollar business.

Smith acknowledged filming during the pandemic lockdown but said she abided by COVID-19 screening protocols. “I have tried to follow all the same practices as every other YouTuber regarding what is required to make a YouTube video and upload it,” Smith said.

Mejia sent a letter on behalf of DLSE to Piper in 2022 advising her that she must comply with child labor laws, according to a lawsuit. According to a spokesperson for the division, who would not confirm or deny that the correspondence was sent, such a letter would “serve as a notice to employers to discontinue unlawful practices.”

In his email to the Squad parent a month later, Mejia said the case had not been presented to the district attorney, adding that “these cases do take time and [it’s] a type of case we have not dealt with. This is new territory.”

Mejia declined an interview request, and the DIR would not confirm or deny that it was investigating Smith. Smith said she was only aware of receiving a “subpoena for business records from the Labor Commissioner.”

How Piper became a star

Piper was watching TLC’s “Toddlers & Tiaras” when she first realized she wanted to perform. She was 4.

“I can do that,” she said, pointing at the television.

“And I can do better than them,” Smith recalled her daughter insisting.

Ever since, Piper said, her mom has supported all of her dreams — no matter how big the sacrifices. Smith’s pregnancy with Piper was unexpected. She was working as a dog groomer at the time, and she said her boyfriend did not want to have a baby because he hoped to become a rock star. Smith kept the baby, living with her parents and raising Piper as a single mother.

“I was never really one of those girls that made not having a dad a personality trait,” Piper said during the Zoom interview, toying with her necklace. “I thought it was cool. I got my mom as my best friend.”

They developed a symbiotic relationship. Today, they interact almost like teenage friends. In conversation, the mother and daughter finish each other’s sentences, giggle at the same jokes and simultaneously bristle at any allegation of wrongdoing.

“I feel like she saved my life,” Smith said, her voice quavering. “I didn’t love myself at all. But when I had her, I just felt like I had a purpose in life.”

Smith was raised in an unstable home. Her parents had a fraught relationship, divorcing and then reuniting a few years after the split. When she was 9, her family moved from Long Island in New York to Canton, Ga., a small town at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Her sister, Patience Rock Smith, 37, said their parents made the move in order to help their father stop drinking; it didn’t work.

Patience remembered Tiffany as a star student who also played flute first chair in the school orchestra. After graduation, Patience said, Tiffany attempted to model and got headshots done.

In an interview, Patience described her childhood home as abusive and dysfunctional. She said that vulgarity was common, and that Tiffany made lewd jokes and often bullied her. Tiffany vehemently disagrees with this assessment, as well as the idea that she wanted to be in showbiz.

Instead, she said, she’s devoted her life to Piper’s career.

“A lot of people think that she’s living her life that she didn’t have and pursuing it through me,” Piper said. “Absolutely not. She’s making this so perfect for me.”

Tiffany Smith said that when Piper was 7, she was feeling “very defeated in the pageant world” and began talking about an app called Musical.ly.

“You could get featured on this app, and you could get famous,” Smith said Piper told her. On the app, an early incarnation of TikTok, users shared short clips of themselves lip-syncing. With Smith’s approval, a friend helped Piper start an account in May 2016, and within months, Piper became one of the more popular creators on the platform, with her name regularly showing up in the top 10 of the ranking board.

In November 2016, Smith took Piper to L.A. to attend a Musical.ly meet-and-greet with other popular users. A social media manager approached them there. He wanted to represent Piper and suggested she start her own YouTube channel.

The family split time between L.A. and Georgia until 2019, when Smith decided to rent a boxy modern apartment in a building near Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street. They soon started working — and living — with Hill, who met and befriended the mother-daughter team through Musical.ly.

Hill moved from Wyoming at 19 in the hopes of becoming an influencer. But after studying the inner workings of YouTube’s platform, he decided to abandon his dreams of stardom to focus on promoting Piper’s channel. He began working as an all-around producer and metadata whiz for PRI, filming and editing content for the Squad while ensuring that videos had tags and thumbnails that primed them for success.

YouTube monetization

To become monetized, accounts need a minimum of 1,000 subscribers and 4,000 public watch hours within the previous 12 months to apply.

Some 2 million accounts have reached that level and have received $15 billion in payouts in 2021, according to ChannelMeter Chief Executive Eugene Lee.

Hill said he took inspiration for the Squad from celebrity boxer and vlogger Jake Paul’s influencer collective, Team 10, which formed in 2016. Paul’s group forged a thriving social media empire through pranks and challenges, and created a blueprint for hundreds of similar collab, or content, houses.

Unlike Team 10, whose members were teenagers, the Squad was composed primarily of tweens, most of whom had their own YouTube channels that Hill managed. If Squad members started to make money off of those channels — and nearly all of them did — they said they paid 10% of their profits to Hill for his expertise.

Eventually, Hill said in an interview, he was producing more than 70 videos for the Squad per month — only a fraction of which were for Piper’s channel. Hill vehemently denies claims of abuse in the lawsuit and said he doesn’t understand why the former Squad members are so upset because “these kids were making more money than my mom makes in an entire year.”

Smith agrees, noting that once their channels were monetized, Squad members were earning “hundreds of thousands of dollars.” This happened even though she says she did not assemble the group as a money-making scheme, but rather because she “sympathized” with how difficult it was for kids “constantly getting rejected and going up for roles against their best friends.”

“So they were coming to me and asking me for help. And, you know, I helped them,” Smith said.

Before Piper became a brand, she would audition for outside projects. But once the Squad formed, she committed herself fully to her social media endeavors. Squad members said they were strongly discouraged by Smith from auditioning elsewhere or signing contracts with others.

Smith said this is untrue but noted that “if we made a specific time commitment to each other ... we would honor that and schedule other projects around it.”

For a time, Piper and many Squad members appeared to be mutually benefiting from the collaboration, earning substantial amounts of money through advertisements on YouTube and brand deals off-platform. How brands and social media platforms broker these deals with minors is a huge sticking point for critics of the business. Companies are making billions of dollars off of content created by children without being held to the same standards as a typical Hollywood production, according to child labor experts including BizParentz co-founder Henry.

“What YouTube could — and should — be in trouble for is their policies about who they allowed to monetize,” Henry said.

YouTube creators need a minimum of 1,000 subscribers and 4,000 public watch hours within the prior 12 months to apply for monetization.

YouTube has about 2 million monetized accounts, ChannelMeter’s Lee said, and in 2021, the company paid $15 billion to those partners.

“That’s why YouTube is still the king of the hill in terms of how creators can make the most consistent form of revenue,” Lee explained. “Monetized views get you paid — likes and engagement don’t get you paid.”

Another way creators make money is through product placement with sponsored content, which has its own set of potential pitfalls for minor performers. The companies advertising on YouTube are getting cheap marketing, providing influencers with free products in exchange for a video, Henry said.

Many influencers making a living from their work would tell you this is a full-time job, said Henry, adding that any brand that aligns itself with channels that are not adequately protecting minors could face public blowback.

“If the kids are wearing Mickey Mouse things and doing a trip to Disneyland, and that’s their placement,” said Henry, “then Disney is in trouble.”

The Disney Channel has partnered with Piper in the past, most recently in August, when she promoted the Disney Channel show “Hamster & Gretel” on TikTok and Instagram. A Disney representative did not respond to requests for comment.

How the Squad joined Piper — and how they left her

Hollywood was the dream. The promised land of content houses with infinity pools, studio backlots and star sightings at breakfast. It was where the Squad kids wanted to be, and their equally ambitious parents moved mountains to get them there, relocating from thousands of miles away — Georgia, Ohio, Texas — for a shot at stardom.

Piper was on the same track, and her path collided with theirs. They’d meet on commercial auditions or the sets of small online productions. Kids with respectable online followings received invitations to collaborate via DMs from Piper’s Instagram account. Acting was the primary goal, but making content with Piper — who was well on her way to gaining millions of subscribers — seemed like a fun way to get some extra exposure.

By 2019, Piper’s impromptu videomaking with friends evolved into a promising business proposition in the form of the Squad. And it was filled with kids who were largely unfamiliar with the rules of a cutthroat, opaque business.

Early videos of Piper and her friends show them competing in goofy challenges, such as staying in a cemetery late into the night and seeing who could remain in a tub of ice water the longest. But nothing performed better than material featuring the Squad’s “crushes.”

Boys and girls were paired in romances that resulted in staged conflict. Piper documented her first kiss with her boyfriend on camera and tried to make her ex-boyfriend jealous with a new boyfriend. She competed with her friends in challenges to see who could lock lips or hold hands the longest.

Jennifer Bryant, the mother of 16-year-old plaintiff Walker, said “crushes” were fabricated between kids who didn’t understand the implications, and that she and other mothers were uncomfortable with the practice.

Piper said that many of the kids had genuine feelings for one another, but that sometimes crushes were created for videos at the request of parents eager for extra views.

“That’s [Tiffany’s] moneymaker,” Bryant said. “Anything crush-related, or boyfriend-girlfriend related.”

Another mother, Angela Sharbino, said Smith told her she used to put Piper and her crush alone in a room together for 30 minutes a day to create chemistry between them. Later, Sharbino said, Smith suggested she try the same tactic with her son, Sawyer, and his crush. (Sharbino said she refused.) Smith says this is untrue, adding that Piper and her crush “naturally had chemistry and enjoyed each other’s company.”

Smith was deeply invested in the teenage romances. According to Squad parent Ashley Rock Smith, Tiffany sent Piper a daily iPhone checklist cataloging the attention she needed to pay to her boyfriend, including sending him heart emojis, giving regular kisses, hugs and loving touches. Ashley said Tiffany urged her to keep a similar list for her 13-year-old daughter Claire to use with her crush. Smith denies this.

Ashley is the wife of Tiffany’s sister, Patience. When they married in 2016, Patience became a “bonus mom,” and gained two stepdaughters: Claire, 13, and Reese, 10. During visits to her native Georgia, Piper collaborated with her eldest cousin on videos — something that made Claire “obviously feel so special,” Ashley recalled. Claire, outgoing and self-assured, later went on to create her own channel; Reese did not.

In 2020, Ashley and Patience moved their hemp business to Las Vegas. With L.A. just a few hours away, Claire could become a more regular member of the Squad. And Patience was hopeful that her strained relationship with Tiffany might be healed through their children.

When Patience took Claire to L.A., they sometimes stayed in Smith’s guesthouse, which was typically reserved for the family’s rescue cats. Eventually, Reese joined the monthlong trips, while Ashley stayed behind to work.

Claire loved being with her cousin. They made chores fun by singing, she said, and they both loved Christmas music. But life in the house quickly deteriorated. The filming schedule was hectic, and Ashley grew worried that Claire was falling behind in school because she wasn’t getting enough sleep.

Smith, former Squad parents said, could be unreasonable and demanding, quick to anger and controlling — and that when anybody spoke up about their concerns, she would gaslight and belittle them.

Smith denies this assessment of her conduct: “There is tremendous personal animosity towards me, which is unfounded, unfair and untrue.”

“The first time I went, I was so excited — until Tiffany started to yell at me and stuff,” recalled Reese, who is more shy and soft-spoken than her sister. “I was like, ‘I don’t want to be here anymore. I want to go home.’”

In June 2021, the Rock Smith family cut ties with the Squad and would join the lawsuit before the year was out.

Even kids who were on the fringes of the group expressed discomfort with Tiffany Smith’s behavior.

Donlad, 15, is one of the only plaintiffs in the lawsuit who came from Southern California — and from money. He and his mother, Yvonne Dougher, live in a $3.7-million angular modern mansion cut into the hills of Los Feliz with a distant view of downtown’s jagged skyline. His father is a real estate investor with multimillion-dollar properties across the Southland, and as a boy, Donlad often showcased his family’s wealthy lifestyle using the moniker “The RICHEST Kid in America.”

In 2020, Donlad said, Smith DMed him through Piper’s account asking to film together. About a week later, the Squad turned up in a Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van at his dad’s Kardashian-esque megamansion in San Diego to shoot a house tour.

Donlad, who never entered into financial agreements with PRI, called the experience of filming that day “chaotic” and “weird.” He made only a handful of videos with the group in eight months, finally stepping away in 2021 after objections from his mom about Smith’s conduct. Dougher’s reservations were intensified by a 2017 video that had been circulating online in which Smith appeared to aggressively kiss a 17-year-old boy.

Parent chatter about the video, paired with Dougher’s bad feeling, was enough for her to ask Donlad to leave. The exit was potentially made easier, she noted, because they were in the unique situation of not needing the money generated by the Squad.

PRI takes advantage of kids who moved here to “make it famous,” Dougher said. “Single mothers using YouTube to support the family — there’s a lot of those in the group.”

Steevy Areeco, the mother of a Squad member named Corinne who had met Piper when both families lived in Georgia, said she was shocked when she saw the 2017 video clip but was told the kiss was consensual. She said she was already leery of Smith and began distancing herself after that.

Some parents of the plaintiffs say they did not view the video until after they left; others, however, say they had seen it. The footage and their stated concerns about set safety and Smith’s allegedly inappropriate behavior were among the reasons they say they pulled their kids from the group.

Even so, leaving the Squad was difficult for many, and not just because of the money. Friendships ended.

Claire tearfully recalled realizing a girl she left behind in the Squad had “deleted all of the photos that we had together off of her Instagram. It was almost like we didn’t exist.”

Serious allegations

When the churn of life with Piper came to a halt, gone was the dopamine rush of social media likes and attention. The kids’ subscriber bases began to dwindle in tandem with their IRL social circles. Some fell into depression. Others stopped making YouTube videos.

Parents were worried, alleging in the lawsuit that PRI harmed their kids’ online reputations and caused a loss of income. It was only when they met with lawyers in 2021 to discuss their alleged claims against Smith and Hill that the kids’ sexual allegations spilled out.

Those allegations, highlighted in the lawsuit, led the FBI to make inquiries into Smith. The bureau’s questions extended beyond the Squad to include a young man named Raegan Fingles. Known as Raegan Beast on his social media accounts, Fingles was the 17-year-old shown in that widely seen 2017 video. His story is contained in one of the prior two lawsuits against Smith.

After coming out as transgender, Fingles left his native Maryland for L.A., where he connected with Piper on Musical.ly, collaborating with her on videos.

After a day of filming with Piper, Fingles said a group that included Hill and two other friends decided to “party and chill” at Smith’s Hollywood Boulevard apartment. He was 17, but Smith “provided alcohol to everyone,” he wrote in a May 2020 signed statement later filed in L.A. County Superior Court. “She drank a lot herself and was extremely drunk.”

At one point that evening, Fingles started livestreaming on the app YouNow. He was seated next to Smith, then 36, on the couch and noticed that she was becoming increasingly touchy with him.

He wrote in the filing that suddenly, “Tiffany grabbed my face and started to French-kiss me. Piper grabbed her by the head and pulled her back to remove her. She proceeded to kiss me again.”

Fingles, who said in an interview he had not kissed many girls at that point in his life, was in shock and turned off the livestream. Piper, then 9, was upset and began yelling at her mom about how she was “gross,” he said in the statement.

Kristen Hancher, Fingles’ friend who was also at the apartment, told The Times that she was alarmed by Smith’s behavior.

“She was the adult in the situation, and she let us underaged kids get intoxicated and forcefully kissed Raegan while her daughter was there watching,” said Hancher, who is also a social media personality.

Despite her daughter’s protesting, “Tiffany didn’t stop coming onto me,” Fingles wrote in the filed statement. “She grabbed me by the waist and tried to pull my underwear. She dragged me into her bedroom.”

Smith denies providing alcohol to minors, and says that the kiss was her response to “a dare during a livestream that was supposed to be good humored.” She contends that the incident “has been greatly blown out of proportion.”

After leaving the apartment, Fingles said he called his manager, Matt Dugan, who also represented Piper. According to Fingles’ statement, Dugan told his client he would “make sure Tiffany [was] stopped and punished.” The following morning, Fingles said he thought “all the reposts of the footage of the live [stream] had been removed from YouTube.” (In fact, a clip of the kiss ultimately remained online.) Feeling “ashamed” and unsure of “what else to do,” Fingles said he let the issue go.

Dugan declined to speak on the record. Smith says she does not recall Dugan talking to her about the incident.

In June, Fingles said an FBI agent contacted him for an interview; The Times reviewed that voicemail. He said he then met the agent for an interview to recount the 2017 incident in an hourlong recorded session.

An FBI spokeswoman, Laura Eimiller, said the agency “can neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation” into Smith.

In subsequent months, the FBI interviewed at least six kids from the Squad’s lawsuit, according to their parents. Some of the plaintiffs said they have shared the allegations of sexual misconduct outlined in their legal complaint.

One of the claims was made by former Squad member Sophie, who said in the lawsuit that she allegedly witnessed Smith “grab Piper’s face and make-out with her.”

In an interview and in the lawsuit, Sophie recalled that Piper tried to push her mother away but Smith replied: “What? I’m just trying to teach you how to kiss. You’re going to want to learn if you’re going to be with [boys].”

Smith strongly denied the claim, as did Piper. “That’s honestly kind of funny that they even said that,” Piper said. “That’s sick to think about.”

Sophie, now 15, said she met Piper in 2017 while filming a web series; they hit it off so well that she and her mother, Heather Trimmer, decided to rent a place with Piper and Smith.

“We became inseparable,” said Trimmer. “Now, I would warn anyone to stay away. I’d rather be broke and working at McDonald’s than to do this path again.”

Trimmer said that life in the house was difficult and chaotic. She recalled visits from both the LAPD and the Department of Children and Family Services while she was living there.

The DCFS declined to comment, but The Times reviewed a letter that the agency issued Smith in May 2020, saying it had closed an open referral into her because it found the allegation of “child abuse and/or neglect” unfounded.

Public records show that the LAPD visited Smith and Piper’s residences six times between April 2020 and April 2022. An LAPD spokesperson declined to comment. Smith acknowledged that police visited her home “in response to a third party who directed minors on social media to make false police reports against me.” Another time, she said, officers arrived after her residence had been vandalized.

Trimmer, a photographer, said Smith often urged the kids to pose more provocatively for thumbnail photo shoots — the images used to promote YouTube videos.

She would frequently tell the Squad members to make ‘sexy kissing faces’ for thumbnails, to ‘push their butts out,’ to ‘suck their stomachs in,’ ‘wear something sluttier’ and would otherwise position Plaintiffs’ bodies in explicitly and sexually suggestive positions,” the complaint said.

Trimmer, who was tasked with ordering clothes for some of the girls, said Smith told her to “make sure Piper’s stuff is slutty. That’s her look.”

Smith said she “never did that.”

Amid rising tensions, Trimmer and Sophie left the house — and the Squad — in late 2020.

The lawsuit also contends that Smith asked Squad members including Corinne, then 11, about their sex lives, encouraging some to “try oral sex.” Corinne said in an interview that Smith once asked her if she’d “ever given a blow job before,” even though the child did not know what the sex act was.

“She was like, ‘I’ll show you, just try one on Hunter,’” Corinne said of the 2019 incident. “She said she was gonna pull his pants down. I was turning away and Piper was, like, ‘Mom, stop!’”

Piper and Hill denied Corinne’s allegation, and Smith said it was “absolutely false.”

She also denied some of the most bizarre claims in the suit—those involving her beloved dead cat, Lenny.

Piper and her mother are serious cat lovers. Trimmer said that when their favorite cats died they were cremated and put on a white Wayfair shelf by the door. She estimated there were at least eight boxes of ashes on the shelf.

One of the family’s favorite cats was Lenny, the kitten Piper got when she was 6. If Piper was anxious before competing in a beauty pageant, “Lenny” — voiced by her mother in a high-pitched, scratchy voice — would give her a pep talk.

Tragedy struck just before Lenny’s first birthday. Piper found her beloved pet “bleeding from every hole in his body,” Smith recalled. They rushed him to the veterinarian, but he didn’t make it.

“So, you know, I mourned Lenny’s death,” Smith said, “but eventually, Lenny started talking again.”

The Squad’s lawsuit states that Smith now uses her “Lenny the dead cat” alter ego for darker purposes. Affecting Lenny’s voice, she would, according to the suit, make vulgar remarks to the Squad members including, “I’m going to f— you up the ass.”

Smith denied making that statement. She maintained that, as Lenny, she never said anything inappropriate in front of children — just in front of adults.

“Lenny, does not talk like that to kids,” she said, adding, “I have no interest in kids, like, that’s disgusting to me. …There was no touching, there was no sexual contact.”

Piper’s cousins, Claire and Reese, allege in the lawsuit that Smith used Lenny’s voice while sitting on a bed and “moving her hand” toward the vagina of her 9-year-old niece, Reese.

In an interview, Reese said she knocked Smith’s hand away but didn’t tell her parents because, at first, it didn’t make her uncomfortable.

“I was like, ‘Oh, it’s a cat. I love cats!’” she said. “So I didn’t really think anything of it.”

Reese said her experiences with Lenny occurred at various intervals between February 2020 and June 2021. The lawsuit alleges that Smith “ambushed” Reese, grabbing her by the neck, tossing her on the bed and, “pretending that her right arm was ‘Lenny’s penis,’” while rubbing it all over Reese’s face, head and mouth.

“She kind of did it in private, and I guess we just thought it was a normal thing for her to do,” Reese said, adding that Smith “would, like, trap you. She would get you in a comfortable position, or get you in a corner, and then she’ll do it without no one looking.”

Smith denied these claims. She said that Reese liked Lenny and would use his voice herself, saying, “I want to be just like Aunt Tiffany.” Patience and Ashley Rock Smith said this was not true.

The lawsuit also alleges that Smith spanked and slapped Claire’s buttocks, poked her anus over her clothing with her finger and attempted to squeeze her breasts.

Smith said that she did play physical games with the kids but insisted they were not sexual. One such game, she said, was called Cow Eat the Corn, in which she would grab another person’s knee in a certain spot to tickle them.

Smith’s youngest sister, Destinee Rock Smith, questioned Claire and Reese’s accounts of being inappropriately touched. In an interview, Destinee said she had a conversation with Patience earlier this year in which Patience cast doubt on her stepdaughters’ stories in the lawsuit.

“You know Tiff didn’t touch those kids,” Destinee said she told Patience. “And Patience said, loud and clear, ‘I know she didn’t, Desi. I know she didn’t.’”

Although the lawsuit alleged sexual battery by Smith, Patience argued that Smith had not molested Claire and Reese.

“I told her she should take a look to see what the actual allegations were against Tiffany and Hunter,” Patience wrote in an email. “Yes, Tiffany inappropriately touched some of the kids but did not sexually molest them. Was there intent? I do not know the answer.”

Numerous Squad members also allege that Smith regularly interacted online with a man posing as a young girl named “Megan” who sent her money, a Gucci bag, laptops, lawn furniture and other expensive gifts in exchange for images of Piper. In the lawsuit, Corinne said she witnessed Smith mail “several of Piper’s soiled training bras and panties to an unknown individual,” adding that Smith told her “old men like to smell this stuff.”

“That’s untrue,” Smith said, about the undergarments. She also said she never traded images of Piper for goods — “Megan” simply sent the goods without asking.

In an interview, Smith acknowledged that Megan “did send Piper a lot of stuff,” including money to Smith’s PayPal account. If she returned the funds, Smith said, Megan would send double the amount. She kept the money and didn’t argue because Megan once sent her a photo of a loaded gun, she said, “and that was a little scary.”

Asked for more information on the identity of Megan, Smith said: “I feel like that is in my past. I’m no longer linked to that person and therefore, I’m leaving that alone.”

Smith and her lawyer maintain that, motivated by greed, the plaintiffs concocted salacious sexual allegations to inflict maximum damage to Smith’s reputation.

She described herself as “a good person” whose main goal has been to “just always make [Piper] happy.” Smith said she regularly contributes money to Piper’s Coogan account and noted that her daughter can spend money through her Apple Pay app on her phone. (Piper described herself as “frugal” but generous with her money.)

Ashley Rock Smith, a former financial operations manager, said during the year Claire was in the Squad, she was alarmed at the rate money was spent by the kids in Piper’s sphere.

“I was watching all this money fly out everywhere,” she said. “These kids were buying Starbucks three to four times a day and would spend $500 on a pair of shoes. I looked at my daughter and said: ‘Girl, don’t get used to this. You’re not getting your nails done every two weeks. You’re 11.’ None of the kids would wear the same outfit twice.”

The lawsuit alleges viewership for Piper’s channel nearly quintupled from 2017 to 2021, during the years that the plaintiffs filmed most actively with PRI and were unpaid.

It also alleges that Hill tampered with kids’ YouTube channels after they left the Squad, using bots and a contact at YouTube, “Alex,” to boost Squad members and quash rivals.

Hill told The Times that he never interfered with or manipulated former Squad members’ channels. He said he made up Alex because he was working constantly for more than a dozen clients and under immense pressure from parents.

“I wouldn’t say I lied,” he said, pausing. “Yeah, I guess I did. … These parents were at my throat like, ‘My kid’s not making as much money this month,’ or ‘This is happening to their video and they’re blaming me for it.’ It was just easier for me to simply be like, ‘Let me go ask someone at YouTube.’”

Smith put it more bluntly: “If we knew somebody on YouTube, would we be demonetized right now?”

Smith and Hill maintain that the former Squad members lost YouTube revenue because they said they were no longer associated with Piper, and thus no longer benefiting from her fame.

“If we’re talking star power, Piper’s the star right?” said Hill. “You put her face on a thumbnail, you’re getting, like, 50% more clicks.”

While in the Squad, Walker’s average monthly YouTube revenue was nearly $28,000, but after leaving, it dropped to just over $4,800, the lawsuit states. Corinne said her career suffered because Smith badmouthed her to potential brand partners; Smith denied doing this.

But Corinne’s mother, Areeco, insisted the lawsuit isn’t just about being reimbursed for alleged lost earnings.

“Corinne played with Barbies, and then all of a sudden, she got transformed into a kid who just knows way too much and doesn’t know what to do with it,” Areeco said. “In a way, my child deserves to be compensated for that trauma, and that type of impact on her childhood years.”

Corinne and her mother have grown closer as a result of the dispute. But at least one Squad member has been estranged from his mother as a result of his participation in the group.

Johna Kay Ramirez claims that her son, Jentzen, now 16, was urged by Smith to end his relationship with his mother. According to a separate ongoing legal dispute in Los Angeles County family court, Jentzen began cutting Ramirez out of his life in 2020, when she sought to remove him from the Squad because she felt it was a “modern-day social media sweatshop.” By April 2021, Ramirez said that Jentzen was seeking to legally emancipate himself.

“Hey so I called the number Tiffany gave me for the emancipation Attorney,” the teen said in a text message sent to a Squad parent that was reviewed by The Times. Five months later, Smith texted Jentzen a Zillow listing for a $775,000 property in Van Nuys. “This would be perfect for you!” Smith wrote.

Smith said she provided support to Jentzen because he was having “family difficulties,” and she sent the listing because she was told that he and his sister “did not want to live with their mother.”

Jentzen did not respond to requests for comment.

An unregulated environment

It would take a major regulatory effort to rein in what critics call the “wild West” atmosphere of social media content creation.

Companies skirting child labor laws is one problem, said BizParentz co-founder Henry.

So too is the attitude of influencers themselves, and the lack of oversight, she said.

Despite their aspirations, many Squad members did not have the level of professional experience to qualify for union membership in SAG-AFTRA, which can protect members from abuses.

SAG-AFTRA General Counsel Jeffrey Bennett said he could not speak directly to the lawsuit against Smith and PRI but that the organization’s position “would obviously, and always be, that when a performer is performing, that’s employment, they’re an employee.”

After YouTube demonetized Piper’s channel in February, Smith and her attorney tried unsuccessfully to reverse the decision.

Shortly after the Squad’s complaint was filed, some brands distanced themselves from Piper. Zuru Toys, whose Mini Brands products Piper frequently promoted on TikTok, said it stopped working with her “when news of this broke.”

Other companies continue their collaborations with Piper. On both her TikTok and Instagram pages, she has recently promoted the child makeup brand Petite ‘n Pretty, Warner Bros.’ “DC League of Super-Pets” and the security software firm ExpressVPN. None of the companies responded to The Times’ requests for comment.

Smith said she fears Piper’s life will be ruined because of the legal drama.

“I don’t care. Make me look like a monster. I’m used to it,” she said. They’re using me. … But they’re hurting Piper.”

Piper said she wants to continue posting on her channels until she hits her personal goal of acquiring 10 million YouTube subscribers (she hit that mark two months after the interview). But she admitted that the lawsuit has taken a toll on her. She’s been eating less because she’s often sick to her stomach.

“I don’t even know who I am anymore because of this,” she said. “I’m just trying to keep up a good look for social media and keep the kids happy. … I feel like everything that I have right now is really getting stolen from me, and there’s no way that I can get it back.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.