These artists are preserving the history of a dance style gay men created in ’70s-era L.A.

In 2011, Lorena Valenzuela packed her bags and flew from her home of Mexico to Los Angeles to compete in a dance battle. The day before the contest, she attended a class at Evolution Studios in North Hollywood focused on “punking” — a series of sharp, fast movements rooted in exaggerated looks and expressive body language that emerged in queer underground Hollywood clubs during the 1970s. A fellow dancer had introduced Valenzuela to the unique style when the two were a part of the Funkdation dance crew. “It really caught my attention — all the lines, all the poses, all the expressions and the energy, the character,” Valenzuela says.

The class’s instructor Viktor Manoel — who was also a judge at the dance competition that year — spotted Valenzuela and asked her to freestyle that day. At the time, she only knew four moves. But that wasn’t enough for Manoel. “He stopped the music mid-freestyle and goes, ‘Really? Is this all you got? Is this why you came all the way from Mexico?’” Valenzuela recalls him saying. “Do it again, for real.”

“I just started throwing myself to the ground, all my clothes were ripped, and I was just going insane,” she says. “This is the moment where I understood what this dance really was.” Valenzuela realized that the movements weren’t meant to look pretty; they expressed the toughest emotions.

Meet the inaugural LA Vanguardia class, talented Latinos defining the cultural landscape of L.A. and beyond.

She went on to land in the top three at the festival that year — the only Latina to place. Eventually she moved to the U.S. so that she could continue to develop her skills as a dancer, and she became a mentee of Manoel’s specifically for punking and “whacking” — a movement that evolved from punking that involves folding one’s arms, swinging one’s hands up and over the head all while one’s chest pops out. (The originators of the style are known as “punkers,” while newer generations of dancers are called “whackers.”) Four years ago, she launched her own dance festival in Los Angeles, Strike With Force, that aims to uphold the history of punking and whacking while fostering a community for a new generation of dancers.

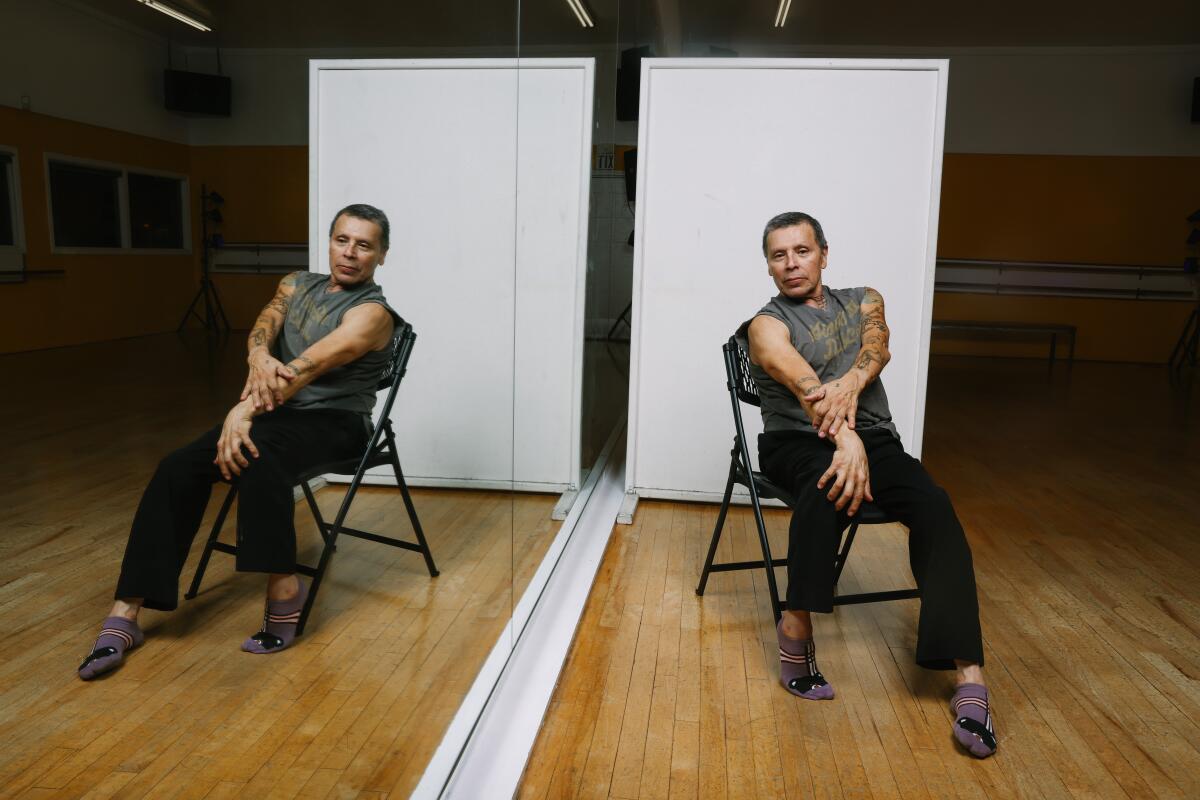

Gay men developed punking nearly five decades ago, while flocking to the safe space of the dance floor. The movement is especially personal for Manoel: After the AIDS epidemic claimed the lives of many of the movement’s founders and the community surrounding it, he is the last founding member of punking alive today. Developed in Los Angeles around the time voguing took hold in New York City, the roots of punking can be difficult to trace — which is why Manoel is determined for new generations to understand the weight that comes with each pose and move. “I’m still fighting for that truth that needs to be told,” he says. “Because the gay culture cannot be forgotten in how this style started.”

When Manoel was 17, in the early 1970s, he went with a friend to the then-Paradise Ballroom on N. Highland Ave, a fake ID in hand. “Men were dancing together and kissing and hugging, and I actually freaked out because when you’re not used to seeing things like this,” he recalls. Manoel had long known he was gay, but was struck by experiencing that for the first time — to the point where he turned to his friend and said: “I can’t. I’m not coming back.”

He eventually returned to Paradise Ballroom and, with friends, started to create a dance that pulled from pop culture, media and art — including Art Deco, paintings by Ballets Russes founder Serge Diaghilev, ice skating and silent movies. Each member drew influences from their own distinct cultures and interests. Manoel grew up dancing ballet folklórico, a Mexican folk-dance style, and often imitated a deer in his performances. And founding member Tinker loved Bugs Bunny and channeled the Looney Tunes character in his movements.

The movements also nodded to how they had grown up at a time when being gay meant not being “allowed to express love,” Manoel explains. “The expression from that oppression via movement is where this punking dance style came into fruition.” To Manoel and his friends, punking spoke to the freedom they found in the club.

In 1978, Manoel and his friends started going to Gino’s II disco on Santa Monica and Vine. Fellow punker Michael Angelo, the DJ on Saturday nights, held contests where accomplished dancers could compete for a $1,000 prize. Punking and whacking had found a new home.

Around that time, Manoel started working professionally as a dancer, performing for artists like Grace Jones. But then his friends began dying of AIDS. “I felt uncomfortable being in a situation where everybody was dying and nobody wants to talk about it,” he says.

He stepped back from the scene. In the meantime, punking and whacking were becoming more mainstream through Soul Train and the Outrageous Waacking Dancers, an L.A.-based dance group. Its popularity grew with a new spelling — using a double “A” — that separated itself from its origins. When Manoel returned to the scene in 2009 to teach punking to new generations, he realized how much of its origins had been lost in translation. That’s changing with initiatives like Valenzuela’s whacking festival, Strike With Force.

During the festival’s first iteration four years ago, Valenzuela invited dancers internationally and from around the U.S., telling them to invite anyone from their community. She then went on to produce other Strike With Force festivals in Italy and Mexico, and smaller gatherings began to pop up as the community started growing. The goal of the festival is ultimately to “empower kids and make them feel safe and make them feel like they belong because this dance belongs to them,” Valenzuela says. “We are the guests.” Strike With Force’s next event is slated for March 2023, in Mexico City.

For his part, Manoel is still teaching the dance’s history and movements. He’s showing one student at a time just what it takes to move as he, Arthur, Andrew, Billy Star, China Doll/Kenny, Lonny, Michael Angelo, Tinker and Tommy all did in Paradise Ballroom. “I don’t teach to impress,” he says. “I teach you how to find yourself in my movement.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.