Rising from the roof of the Orange County Museum of Art is a massive shimmering chimera, a reclining male nude whose face is an African mask. The body is done in the style of Classical sculpture, inspired by a popular pose showing Zeus bearing a cornucopia. The figure’s head draws from the highly stylized aesthetics of the Baule culture of the Ivory Coast — in this case, a double-faced mask, a symbol of duality.

If this sculpture by artist Sanford Biggers feels a bit like an illusion, that’s because it is. Seen from a distance, the contours of its body indicate depth, but the work is actually flat — a piece of aluminum supported by a scaffold. On its forward side, Biggers renders this deity in different tones of fluttering sequins crafted from stainless steel; on the other, where the scaffold’s supports come into view, he has painted a pattern of black and white octagons borrowed from a vintage quilt.

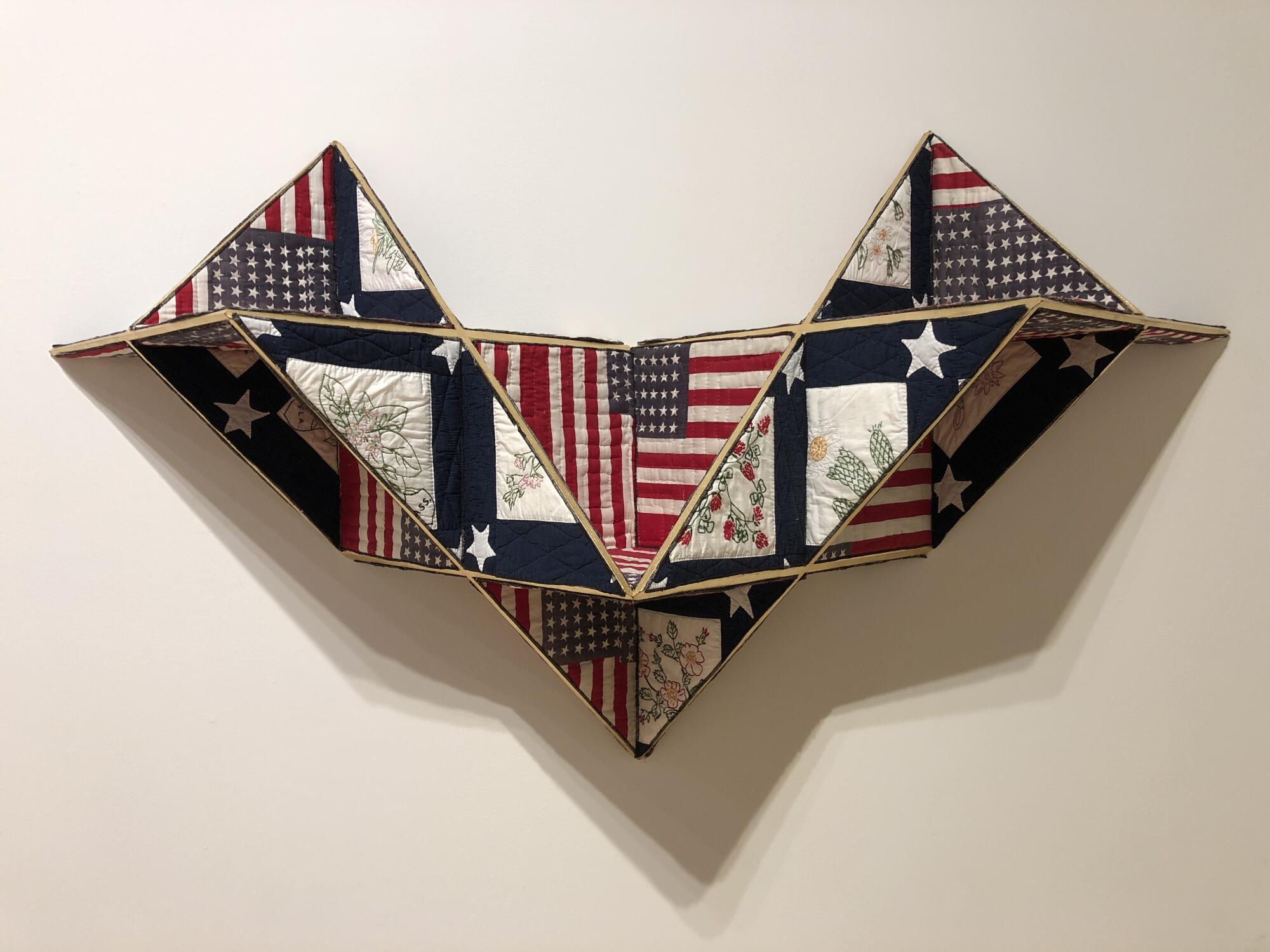

“Of many waters...,” as the piece is titled, brings together several important threads in Biggers’ work. There is his “Shimmer” series, which renders the silhouettes or shadows of figures in reflective materials such as glitter and sequins — depictions that turn the nebulous into powerful presence. In the “Codex” series he employs vintage quilts as canvases for paintings or uses them to create geometric, sculptural forms — works that feel like portals. And there’s the “Chimera” series, featuring Western-style figures, generally rendered in marble or bronze, with their faces obscured by African masks.

These pieces have been materializing in myriad places, as visions do.

Last year, one of his chimera sculptures was realized at an industrial scale in Rockefeller Center in New York City. This was followed by an enthralling exhibition of his quilt works, titled “Codeswitch,” at the California African American Museum. In addition to the rooftop sculpture at OCMA — which will remain on view through next summer — some of Biggers’ quilted works will go on view at the Skirball Cultural Center next month as part of the group show “Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories.”

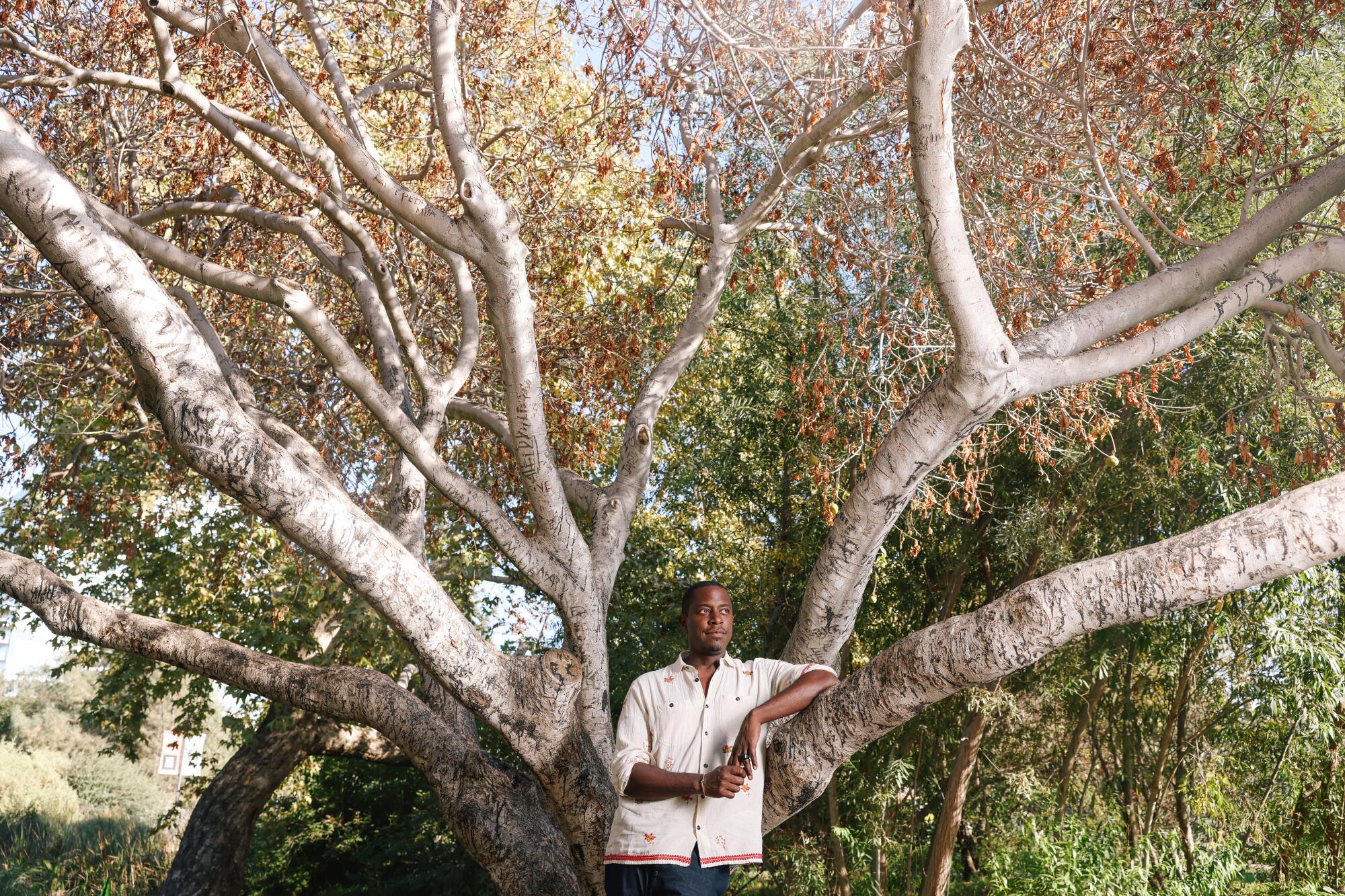

Though the artist lives in New York, he was born and raised in L.A. — and was recently in town to oversee installation of his work at OCMA’s new building in Costa Mesa. In this conversation (which has been condensed and edited for clarity), Biggers talks about why his new chimera dons sequins, his side gig as an experimental musician and that one time he had dinner with Prince on Olvera Street.

The “Chimera” series features these complex hybrids of European art-historical figures donning African masks. Is this Modernism revealing its roots? European cultural appropriation exposed?

It’s all of the above. It’s about the masquerade — the person who wears the mask being able to act their true nature. Sometimes the mask is to hide their true nature. Is the mask wearing the person? Or is the person wearing the mask? Is it symbiotic or parasitic? I think about the cross sections of history. We’ve all benefited from some cohabitation and commingling, but it’s problematic and fraught with lots of issues.

I’ve referred to some of these as objects for future ethnographies. I imagine people researching our time in history and finding these objects and trying to figure out what the narrative is.

What determines the materials for this work? Why sequins?

I have signature themes and over the last several years it’s been the chimera sculptures and the quilts. I wanted to use this as an opportunity to think about the two together. How can I make a quilt work that can be outside and allow me to play with scale on a different level? Around 2016 or 2017, I started doing things with sequins on some of the quilts. I would create the outline of the body using sequins. But those couldn’t go outside. So this was a way of experimenting with that.

Sequins are also generally associated with women’s craft.

There are political ways to speak about it, but there is also a general passion for materials. I was always interested in the object that wasn’t the exalted object. I used to spend a lot of time with my mom in various fabric shops. When I was in grad school, I was in a painting program, but all my work was sound and installation and sculpture. I worked with fiber artists — which was often looked down upon because of its association with craft. I grew up as a graffiti artist in Los Angeles — that’s how I started making art — so, for me...

You were a graffiti artist? What was your tag?

I was Midas. I was all over Pan Pacific Park!

So, I was always drawn to works that were on the outside of contemporary art. I didn’t really buy into the notion of art versus craft. I always thought the best art had a bit of both.

It took 35 years, but the Orange County Museum of Art has a new home.

Pattern — and plays on pattern — continuously emerges as a facet of your work. What does pattern allow you to communicate that a literal drawing might not?

Rhythm. Visual rhythm. Cadence. There’s a frequency that I think patterns can create. When you disrupt a pattern it is almost jarring to the eye. Something about that phenomenon is fascinating to me. One of my influences was [painter] John Biggers — he was a cousin. His research in painting started to expand when he went to Ghana in 1957 and started looking at textiles and translating that to his paintings of the rural South and shotgun shacks. Conceptually I see myself as maintaining that tradition, but finding my own materials and voice.

I read that your quilt pieces were inspired, in part, by the idea that quilts may have served as directional markers on the Underground Railroad during the era of slavery. What intrigued you about that idea?

It was really a heightened moment about coding in the early aughts — computer coding. So when I started researching quilts, I was interested in the conversations about code. What if I took a code and imposed a different code on top? There is tension there. I was also thinking about myth. All these works of art we’re talking about now, referencing river gods and Roman history, you’re talking about myth. I was interested in the myths of the Underground Railroad. Artists are mythmakers. Through those myths you find truth.

A quilt becomes a painting at the California African American Museum in L.A.’s Exposition Park.

How do you approach the quilts themselves? Are there patterns you’re on the lookout for?

Sometimes I have no choice. I come to the studio and somebody leaves a box of quilts because that’s what I do. So I allow those quilts to tell me what to do. That’s in the history of patchwork quilts: You take what you have, you don’t discard. You find a way to make it work.

You embedded a QR code into one of your quilts that sends viewers to videos by Moon Medicin, your musical ensemble. Who’s in the group and what are you playing these days?

We just performed last week in Detroit. We just pressed an LP with Jack White’s Third Man Records. The cover art was done by the photographer-artist Awol Erizku. Martin Luther [McCoy] is lead guitar and vocals. He’s part of the San Francisco Jazz [Collective]. Jahi Sundance is a turntablist. Our bass player is André Cymone who was part of Prince’s original band. Mark Hines, he does all the tech. I’m keyboards. [The LP] literally just got packaged last week. It’s called “The Great Escape.”

We’d call it art rock, influenced by the Talking Heads, Kraftwerk, Sun Ra. It’s rock, fusion, soul, jazz. You definitely feel hip-hop in there, but no one’s rapping. We have capes — some quilted capes. In the past, we’ve had white customized coveralls that are spray-painted. We also wear masks. Back in one of the early New York gigs, we wore leather pants, no shirts, body oil and glitter.

Saturday’s Orange County Museum of Art gala marked the debut of the institution’s new $94 million building, which opens to the public Oct. 8.

Who were the L.A. artists that were formative to you?

Samella Lewis, Charles White and Varnette Honeywood, who is a very important mentor to me. She and I met when I was in L.A. and considered myself an artist but didn’t know what to do. She took me under her wing and put me in some shows.

My parents were collectors of prints, and we would see shows here [at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art] regularly. The King Tut show, I saw it here. Every summer camp, we’d come to shows here. We’d also go to the tar pits.

It seems every L.A. kid is shaped by the Tar Pits and Olvera Street.

I met Prince at Olvera Street.

How did that happen?

My father was a neurosurgeon and his accountant was also Prince’s accountant. I had one of his 45s and I was hooked: “Soft and Wet.” The accountant knew I loved Prince and when Prince would visit him, he’d bring him music. The accountant wasn’t into it, so he would give to my dad, and my dad would give it to me. I still have most of it.

Somehow it was arranged through the accountant and a friend of the family, who said, Prince is going to be with his people at this dinner and we’d like to invite you. I just sat at the table and looked at Prince the whole time. And when he looked at me, I would look away. [Laughs.]

When you’re back in L.A., what are the things you absolutely cannot miss?

I like to go to that interdenominational garden off of Sunset — the [Self-Realization Fellowship] Lake Shrine. It’s beautiful and peaceful and meditative and near the beach. I used to take my mom there when her Alzheimer’s started. She loved flowers.

Also, El Compadre. I love that. That is my place. I pair that with a run to Sam Ash. I get a hard taco combo and every now again, the shrimp cocktail. And, of course, the flaming margaritas.

Sanford Biggers: Of many waters...

Where: Orange County Museum of Art, 3333 Avenue of the Arts, Costa Mesa

When: Through Aug. 13, 2023

Admission: Free

Info: ocma.art

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.