Billy Al Bengston, Ferus Gallery pioneer and purveyor of custom car culture, dies at 88

Billy Al Bengston, the artist who helped establish L.A. Cool School at the Ferus Gallery through his geometric brand of West Coast, custom car-culture inspired Pop art, has died. He was 88.

Bengston died of natural causes at his home in Venice, said his gallery, Various Small Fires, on Sunday.

Bengston came of age as an artist in the late 1950s, as part of a group of young West Coast contemporary art luminaries including Ed Ruscha, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin and Larry Bell, who helped cement the legendary status of Walter Hopps’ Ferus Gallery as a counterculture hot bed on North La Cienega Boulevard.

Pop art was just emerging and Bengston spoke its language well with his simple, aesthetically direct and repetitive motifs. His shiny, heavily lacquered surfaces also earned him associations with “finish fetish.” But it was his flamboyant personality, colorful sartorial choices and love of California custom car, motorcycle and surf culture that came to define him as a person and an artist.

He staged five solo shows at Ferus Gallery, including his debut in 1958, and once posed on a motorcycle for the cover of a Ferus catalogue in 1961. In the 1960s he elevated his love for sleek metal via his critically acclaimed “Dento” series, which he created by whacking away at his aluminum paintings with a ball-peen hammer until the metal was satisfyingly dented, dinged and rippled. This technique effectively laid all suggestions of overtly sleek finish fetish to rest.

Bengston’s signature symbol was a chevron — or sergeant’s stripe insignia. It appears in many of his works, including his famous chevron paintings from the 1960s. Known as a bad boy with an unfiltered ability to say whatever was on his mind, Bengston’s art was considered masculine and militaristic. Although that critical inclination was belied by Bengston’s reoccurring use of flowers and irises, and later in life, hearts, which he called “Valentines.”

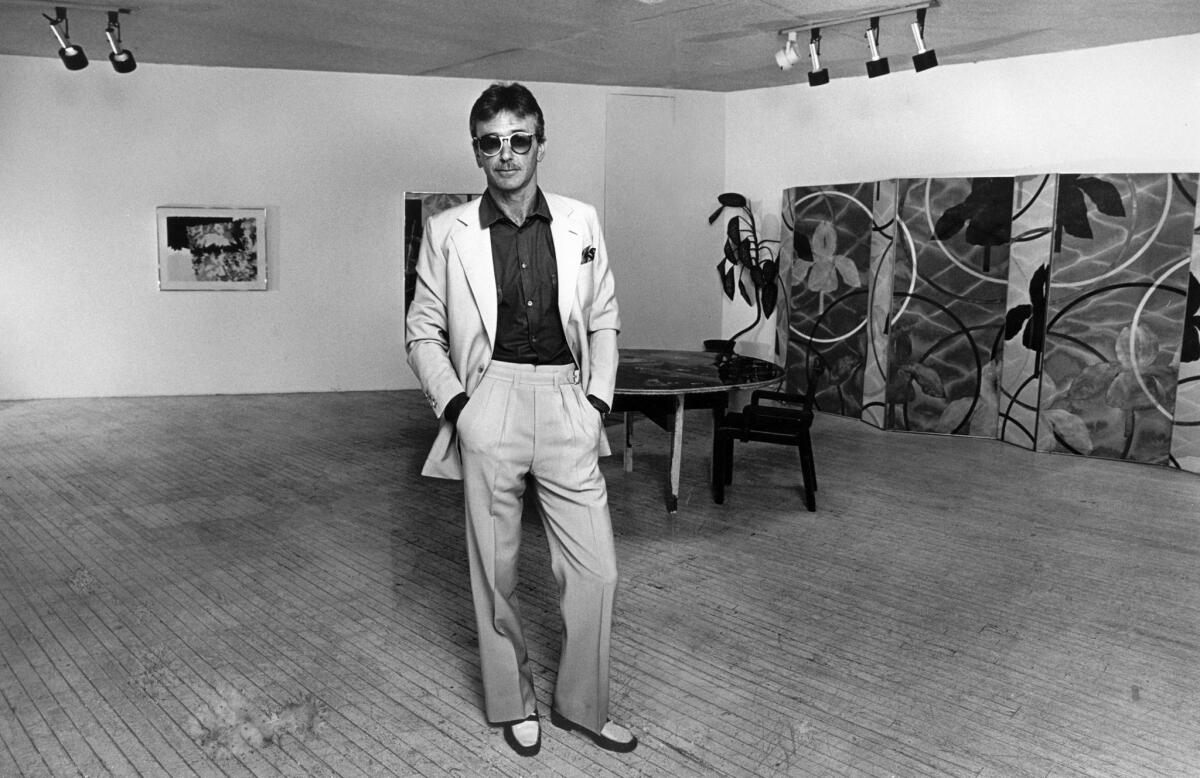

At 54, Billy Al Bengston looks like he’s got it all.

“My soft stuff is a lot more serious than it looks and my serious stuff is a lot more whimsical,” Bengston told The Times in a 1988 interview on the eve of an unprecedented second retrospective of his work at Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “It takes nerve to be light-hearted. You know you’re going to get dinged for it.”

At that time, he was rumored to be the richest artist living in Venice, along with his best friend, the sculptor Robert Graham. He mused that as an artist he had become an entertainer of sorts, and admitted he had always harbored secret dreams of becoming a celebrity.

More than 20 years later, Bengston returned to his roots by re-creating the Ferus Gallery inside the Samuel Freeman Gallery in Bergamot Station. The show was in honor of the 50th anniversary of Bengston’s second solo show at Ferus and it featured paintings from that exhibition within a scale replica of the decidedly humble and exceedingly compact Ferus Gallery.

Billy Al Bengston re-creates Ferus Gallery at Samuel Freeman

“Billy knows that to present a beautiful painting on a white wall with a monochrome floor is to suck all the life out of it,” Freeman told The Times before the show opened in 2010.

Billy Al Bengston was born in Dodge City, Kansas, in 1934. His family moved to Los Angeles in 1948 and Bengston soon became enamored with the sun, the sea, the wide-open spaces — and the fabulous cars — of the quickly growing metropolis.

A rebellious youth, known for mixing good fun with a bad-boy persona, Bengston managed to get kicked out of both Los Angeles City College and Otis Art Institute. He also studied painting under Richard Diebenkorn at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland.

It was at Ferus that Bengston began to flourish, making a name for himself in the heady days when Pop art and Abstract Expressionism were coalescing into something new, edgy and unexpected.

Bengston seemed tailor made for that particular moment in history, and his legacy is forever linked with an era when artistic and cultural anarchy reigned and it was still possible, as Bengston was fond of pointing out, to create something new that referenced nothing other than itself. (In 2010 he cheekily told The Times that he had created the most modern painting ever in the 1960s.)

He also made a point to elevate other artists. Frank Gehry, who designed the installation of Bengston’s 1968 LACMA retrospective, says that Bengston “welcomed me in as an artist to his world, when I was just starting out. That was really important to me — I was invited into the family.”

For the record:

2:46 p.m. Oct. 10, 2022An earlier version of this article reported that Bengston’s art is in the permanent collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The Corcoran closed in 2014. This version has been corrected.

Bengston’s work is in permanent collections in the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; the Honolulu Museum of Art; the Chicago Art Institute, Illinois; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

“His passing has left a huge hole in me,” Wendy, his wife, told The Times. “But he belonged to everyone.”

Times art critic Christopher Knight contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.