Review: Francis De Erdely is a painterly footnote to L.A.’s art history

Is Francis De Erdely a master of radical painting who worked in Los Angeles in the years following World War II but has since been unjustly forgotten?

That’s the peculiar contention being made in a small exhibition at the Laguna Art Museum, which means to revive interest in the Hungarian-born artist, who died in 1959 at the youthful age of just 55. The work doesn’t come close to supporting such a bold claim. In reality, a conservative, if socially conscious, painter occupies a modest historical nook.

The show’s catalog is the first substantive publication on the artist, so it does begin to fill a gap regarding a painter who should be better known, even if he doesn’t measure up to his first- or even second-tier contemporaries. He was somewhat prominent during his day, and it’s worth knowing why. But the book’s also a mixed bag.

The best part: We get a considerable amount of biographical information, helpful in sorting through the show’s 24 easel paintings and 15 works on paper. (He was a gifted draftsman; the drawings stand out.) De Erdely was born in Budapest in 1904, growing up during a period of extreme social distress, political chaos and epic bloodshed.

As history unfolded, he was receiving both a classical education and an academic training in art, beginning at age 15. He studied and worked in Spain, France and Belgium, finally fleeing Europe in 1939, threatened by the Gestapo for his outspoken antifascist activities. With one world war behind him and another about to explode, he emigrated to the United States, living first in New York, then Detroit, largely supporting himself with commissioned portraits. In 1944, De Erdely arrived in L.A., joined the USC faculty the following year, and taught academic painting there until his death.

The catalog’s low point: An art dealer at a commercial gallery that has handled De Erdely’s work was invited to write the enthusiastic introduction. The conflict of interest for what purports to be a scholarly and independent museum study is obvious and disappointing. LAM should know better.

De Erdely occasionally turned to still life, but he was primarily a figure painter. As befits his biography, his art is an uneasy union of firmly academic discipline and the socially conscious subject matter that had gained traction in American painting in the 1930s. Workers are a common theme, from a hard-hat laborer to a newspaper seller, while Black and brown people, as social outsiders, are plentiful. He worked from live models, usually nonprofessional.

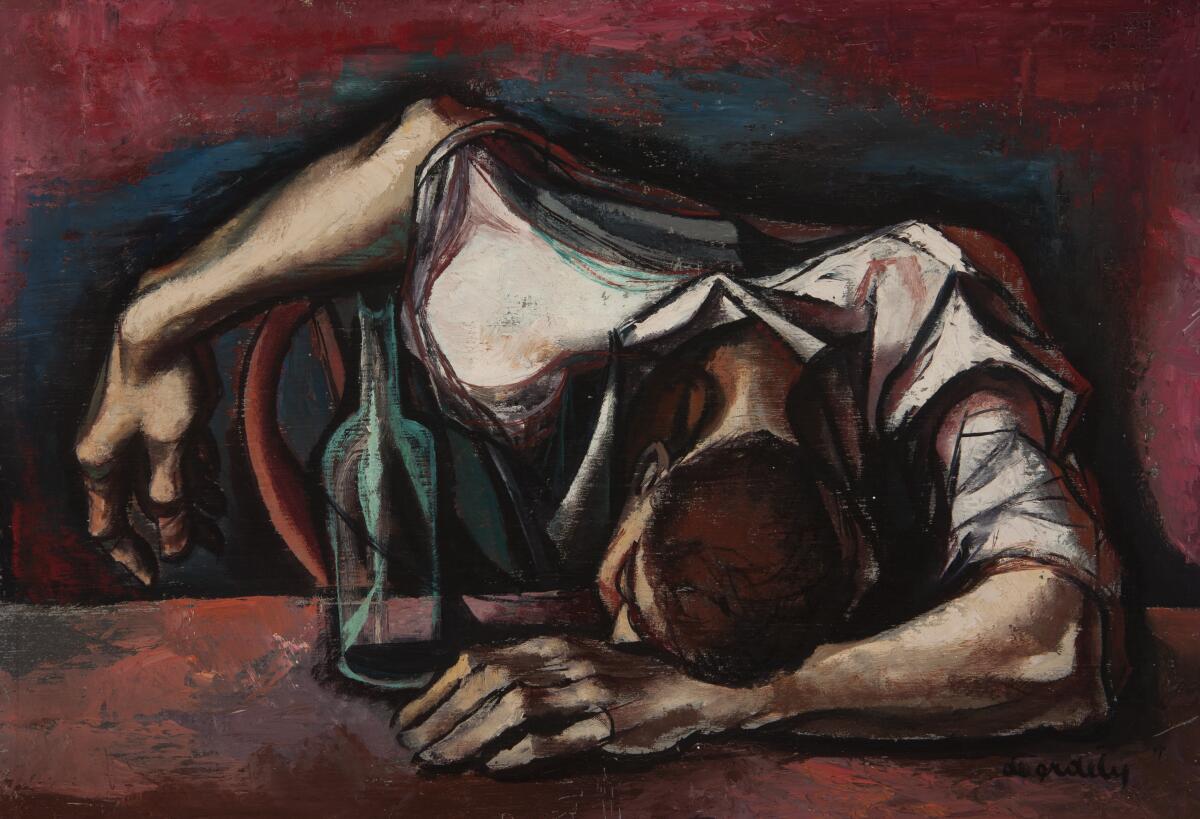

With scant exception, the faces are downcast and worn. Even an image of a man cautiously said in the painting’s subtitle to be resting — one arm slung over the back of a chair, his head lying on the other forearm spread out on a table — is pointedly juxtaposed with an empty wine bottle, compositionally wedged between bony hands. Resting, or passed out?

The spectacle of modern life as a debilitating circus, familiar from predecessors as diverse as Picasso, Georges Seurat, Charles Demuth and Walt Kuhn, turns up in the disheveled figure of “Huey the Clown,” his feeble smile painted on. In a small still life centered around candlelight, the traditional symbol of hope and illumination, the candlesticks are broken.

Stylistically, De Erdely could do straightforward realism, as in an exhausted figure of “Pancho,” resting limply on a bench. Most often, though, he melds the Cubist facture and Expressionist gesture that were at a cutting edge in Modern European painting during his youth.

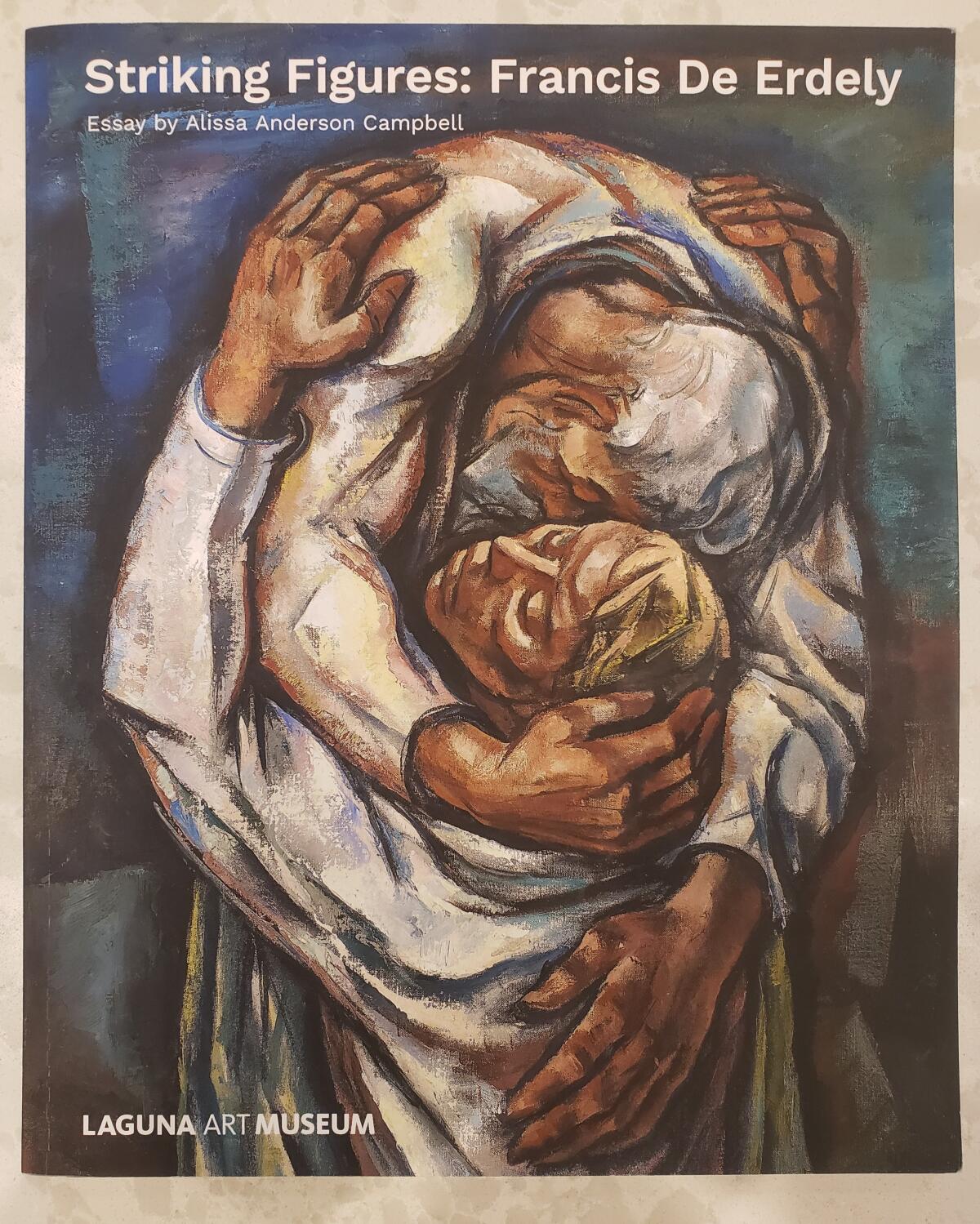

“Return of the Prodigal” (1950) is the show’s strongest picture, notably reproduced on the catalog cover. Father and son, no longer estranged in this parable of a wayward child’s redemption in the face of a compassionate adult’s unconditional love, embrace in a dramatic whirlpool of hugging arms and clasping hands. They are seen from an aerial vantage point — a celestial view, which the artist frequently employed — and rendered in stark contrasts of dark and light.

As he often does, De Erdely outlines their body parts in thick black lines, producing even greater contrast. (The artist had studied at Madrid’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts in his 20s, and certain Spanish Baroque techniques never left him.) Both figures are dressed in white enlivened with primary flashes of pale blue, red and yellow. The creases and folds are also principally rendered in linear strokes of darker paint, as if the forms are carved into space.

More than anything, though, the composition and its palette seem indebted to a painter like Viennese Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka, whose famous allegorical self-portrait with his lover, Alma Mahler, finished in 1914, shows them locked together and floating anxiously in a turbulent swirl. Set in an abstract field of darkly brushed color, De Erdely‘s portrait steadies Kokoschka’s turbulence. He bows the old man’s head in gratitude, while the young man’s is uplifted if unemotionally resigned. The anonymous father’s face is hidden, the son’s haloed by golden hair. Light pours down into the darkness and onto the pair from an unseen source.

The painting’s secular reinterpretation of the famous New Testament story (Luke 15:11-32) is plain to see. De Erdely was among a number of postwar L.A. artists — among them Eugene Berman, Howard Warshaw and especially Rico Lebrun — who were committed to artistic representation of what was broadly known as “the human condition” (almost always battered and grim). Abstraction or nonfigurative art was held, if not in some disdain, at least as something less pressing.

Like De Erdely, Berman and Lebrun were European immigrants; Warshaw came West from New York. Settling in a relatively new city that had scant opportunity to see historical examples of European and American art, it’s as if they decided to fill a gap with well-crafted pictures.

Guest curator Alissa Anderson Campbell identifies the artist’s radical political views, but their disjunction with his commitment to traditional, even conservative painting styles remains a conundrum. If De Erdely’s personal politics might be called radical — or at least liberal, especially in the context of the city’s thumping conservatism during the Red Scare era — his art was not.

Other art was. While De Erdely was painting “Return of the Prodigal,” John McLaughlin was beginning to strip down the geometric abstraction of Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian into a perceptual simplicity inflected by Asian aesthetics that, a decade later, would give birth to the Light and Space movement. Wallace Berman was cobbling together bits of refuse into sanctified objects of humility that would yield a widespread Assemblage art faction.

When De Erdely died, a cadre of younger artists did not pick up his thread and weave it into the 1960s. In the end, artists do have the final say. That, rather than a disinterest among art historians or critical arguments about figurative work versus abstraction, as the show proposes, is the primary reason that his art slipped into obscurity. De Erdely is a curious footnote in the avant-garde story of postwar L.A. art.

Twenty-one art shows, theatrical productions, classical concerts and operatic works our arts critics are looking ahead to in the coming months.

'Striking Figures: Francis De Erdely'

Where: Laguna Art Museum, 307 Cliff Drive, Laguna Beach

When: Thursdays to Tuesdays, 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Closed Wednesdays. Through Oct. 23.

Info: (949) 494-8971, lagunaartmuseum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.