A new Academy Museum exhibit gives early Black trailblazers in film their due

When documentary filmmaker Madeline Anderson was 12 years old, she knew that she wanted to make movies. She also knew that she didn’t like the way Hollywood portrayed Black people — and decided to do something about it.

A civil rights activist before she became a filmmaker, Anderson, 94, joined NAACP’s youth organization while still a teenager growing up in Lancaster, Pa. She made her first documentary in 1960: “Integration Report I,” a 20-minute short on the civil rights struggle in Alabama, Washington, D.C., and Brooklyn during the 1950s. It was the first documentary film produced and directed by a Black woman.

Anderson also has been credited as the first U.S.-born Black woman to produce and direct a TV documentary, 1970’s “I Am Somebody,” about Black female hospital workers who went on strike for fair wages in Charleston, S.C. She went on to have a long career in public television via New York City’s public TV channel WNET, where she became a film editor, writer and a producer-director for the “Black Journal” series. She also helped to launch WHUT-TV at Howard University, one of the country’s first Black-owned public television stations.

Despite these illustrious credits — as well as a celebration of her work by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2017 — Anderson recalled toting reels in film cans to church auditoriums and her kids’ schools just to find an initial audience. “Most people don’t even know about me,” she said during a recent conversation from her Brooklyn home.

They will now.

Anderson’s trailblazing contributions to filmmaking history — and her film “I Am Somebody” — are displayed in the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures’ exhibition “Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971.” The exhibition, which opens on Aug. 21 and runs through April 9, highlights the work of Black creatives from filmmaking’s early days through the civil rights movement.

“Regeneration,” the second major temporary exhibition to be organized by the museum, takes a visitor through seven galleries, tackling themes including the representation of Black people in early cinema (1897-1915), the era of “race films” made by Black filmmakers for Black audiences (1910s-1940s), musical films and stories born of the civil rights movement.

The galleries include costumes, movie posters and such gems as tap shoes worn by the Nicholas Brothers, one of Louis Armstrong’s trumpets and Lena Horne’s dress from “Stormy Weather.”

The exhibition culminates with films made in 1971 — the same year photographer Gordon Parks’ action movie “Shaft,” starring Richard Roundtree as the coolest private detective in Manhattan, blasted onto the screen. With a budget of only $500,000, “Shaft” raked in about $12 million at the box office, proving Black talent could bring in big money and introducing Hollywood’s so-called Blaxploitation era.

So why not start the show in 1971, instead of ending there? The co-curators of the exhibition — Doris Berger, vice president of curatorial affairs at the Academy Museum, and Rhea Combs, director of curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery — found themselves more interested in exploring a little-known era of independent filmmaking in which Black artists told their own stories free from the influence of Hollywood racism and stereotyping.

The time frame also provides a framework to delve into the first generation of Black-owned film distribution companies as well as inclusion of “the Soundies,” three-minute musical films that screened on Panoram machines found in train stations, nightclubs and other public places. Black performers usually were placed at the end of a reel of eight Soundies, but it gave their performances wider exposure than they would get in live shows on the often segregated nightclub circuit. “Regeneration” includes a vintage Soundie machine where visitors may view a reel of eight films featuring Black artists.

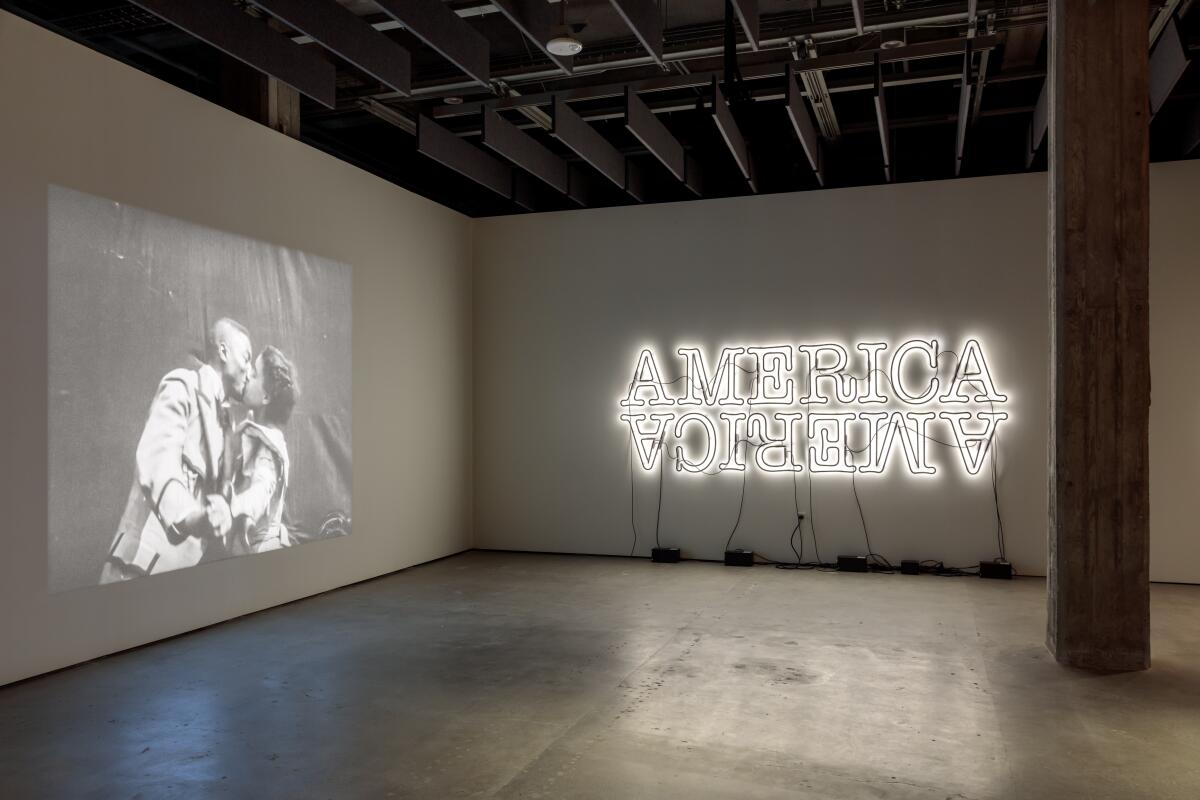

Berger cited the 1898 silent film “Something Good — Negro Kiss” — playing on a loop as the first image a visitor sees — as a first example of a film “presenting African American performance on screen in a dignified way.” The three-minute film, discovered at USC in 2017, features vaudeville performers Gertie Brown and Saint Suttle in a flirtatious courtship. As the exhibition notes, the film depicts perhaps the first onscreen example of African American intimacy.

Combs said that one reason the curators opted to include contributions from the year 1971, instead of stopping just before then, was to include the work of a lesser-known Black Los Angeles filmmaker, Robert Goodwin. His best-known film, “Black Chariot,” about a young man who joins a Black nationalist group, was released that year. Though “Black Chariot” sometimes gets lumped together with Blaxploitation movies, this independent film existed somewhere outside of the commercial wave that turned “Shaft” director Parks and director Melvin Van Peebles (1971’s “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song”) into Hollywood heavyweights during that era.

Recognizing independent filmmakers during this particular time period, Combs added, helps illustrate that “there was still a vibrant ecosystem of artists who were making a way out of no way, if you will, that were finding and creating opportunities for themselves … as well as artists looking beyond the boundaries of the United States, how they had to go internationally for some opportunities as well.”

Los Angeles film director Charles Burnett, 78 (“Killer of Sheep,” “My Brother’s Wedding,” “To Sleep With Anger”), who served on a team of advisors to the exhibition, said building his own confidence as a Black artist might have been easier had he known that the rich history of Black filmmaking dated back to 1898. “This has been eye-opening for me — I felt as though I was shortchanged,” he said. “I would have been a different person if I had understood that.”

Academy Museum President Jacqueline Stewart, named in July from her previous post as the museum’s chief artistic and programming officer, said “Regeneration” has been in development since 2017, but the opening is particularly timely. “I think it was really fortuitous that the museum opened when it did [in September 2021], after the pandemic, after so many delays,” she said. “The social and political contexts made the value of an institution so much more obvious. … We need to talk about these racial histories, and histories of class conflict and labor relations. These are the things that the studio system, and Hollywood, are dealing with.”

For her part, director Anderson said the movie business has come a long way since she and fellow Black filmmakers hand-delivered their movies to churches, schools and segregated theaters to find an audience. She won’t be coming to the opening of the exhibition because of her age and COVID-19 risks, but she’s open to long-distance networking in case Hollywood is listening.

“At 94, I’m making another film, and it’s a memoir film, and I’ve finished the development of it,” she said. “Now I’m back to where I was 60 years ago — looking for funding.”

'Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971'

Where: Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, 6067 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

When: Sundays-Thursdays 10 a.m.–6 p.m., Fridays-Saturdays 10 a.m.–8 p.m. Aug. 21 through April 9

Info: [email protected], (323) 930-3000

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.