If land can be said to contain history, a repository of all that occurs on its surface, then the granite boulder I find myself scrambling over on a very warm Tuesday morning could be said to be one of its important archival artifacts.

Situated next to a small spring in Topanga Canyon, not far from the whoosh of Malibu traffic on Topanga Canyon Boulevard, the boulder at first glance may not seem remarkable. But artist Mercedes Dorame guides my eye to an indentation on its surface: a palm-size carve-out that served as a bedrock mortar, the sort of tool that some of the Santa Monica Mountains’ original inhabitants, the Tongva and Chumash, would employ to grind acorns and other foodstuffs.

“Human hands made it,” says Dorame. “That’s why the grinding bowl is important to me.”

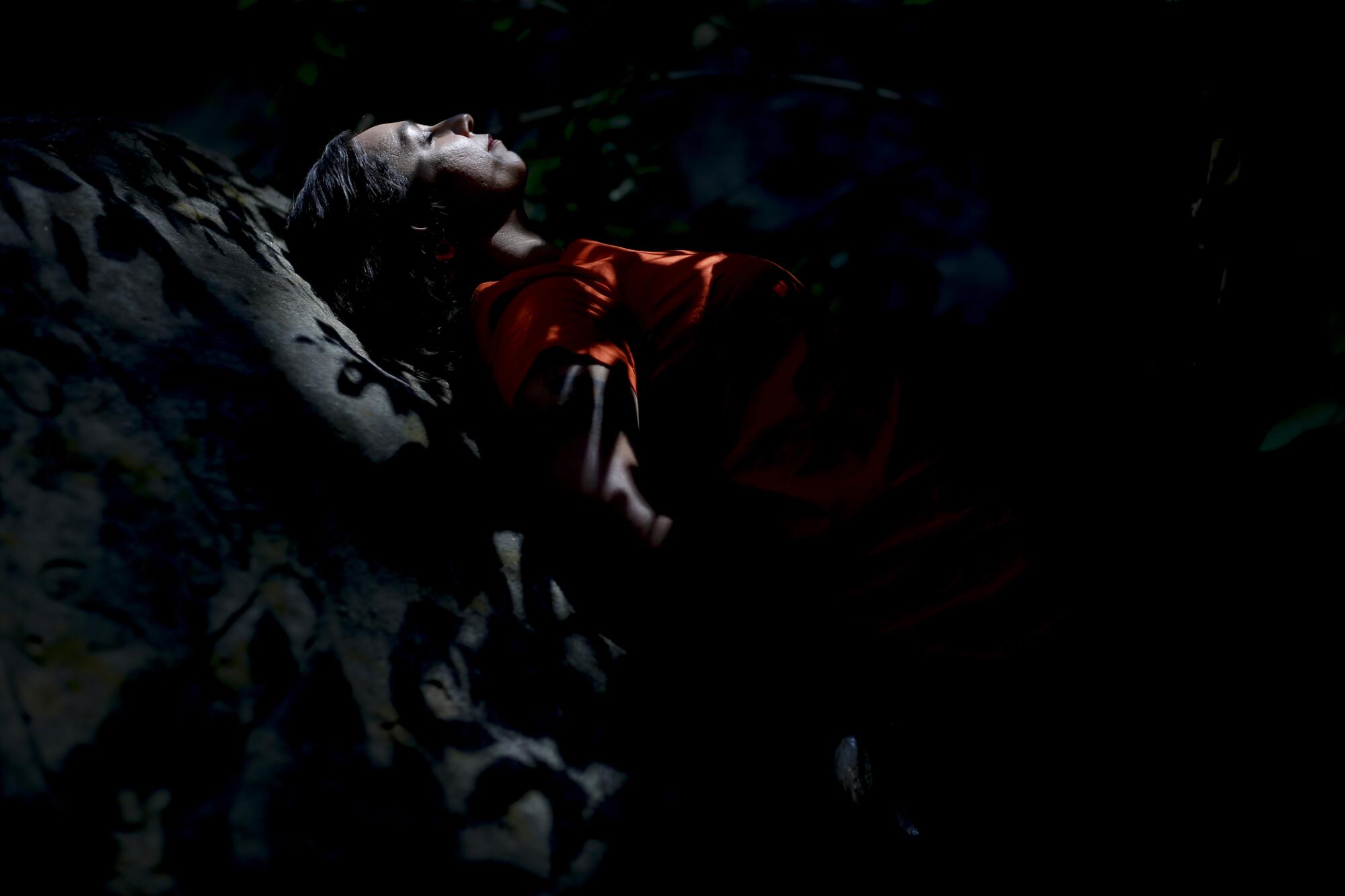

The grinding bowl is at the heart of a photograph she made in 2013 titled “Well of Moon and Sky — Kotuumot Kehaay,” currently on view in “Borderlands” at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino. In her image, the bowl is filled with water, reflecting the sky. Surrounding it are oak leaves as well as ghostly stencils of those leaves made with ocher and cinnamon. Nearby rests a portable metate (mortar and pestle) that once belonged to her grandmother.

If the granite in her image speaks to earthy permanence, the materials on its surface indicate something more evanescent. “The powdered pigments and cinnamon,” says Dennis Carr, the Huntington’s chief curator of American art, who organized the exhibition, “it feels like it could blow away.”

Dorame, 41, is a born and bred Angeleno of Tongva heritage on her father’s side and English, Scottish, French and German on her mother’s.

Her work, in quiet ways, illuminates how Indigenous life and thought remain present in Los Angeles and its landscapes. The spring she has taken me to is a spot that her father, Tongva elder Robert Dorame, took her to when she was a child. It is a place that was part of her family’s story and that is now her story, a story she will pass on to her daughter. That vitality, that lineage, is something she seeks to embody in her images.

The Tongva are not a federally recognized tribe and therefore do not have a territory of their own. So the artist, who works primarily in photography and installation, makes her images in the bits of L.A. landscape available to her: the city’s parks, the hills along the coast, the overlooked patches of land that occupy the spaces between all the concrete. To these settings, she adds objects of her own: a bundle of sage, an abalone shell, an animal skin, splashes of pigment, a red thread that winds through vegetation like the vaporous trails of a spirit.

“I could have gone and just taken pictures of the boulder,” Dorame says of her image of the bedrock mortar. “But for me, my intervention, why I make things myself, why I have my hand in it, it’s because it also reiterates: I’m Tongva. I’m here. I’m making now. I’m in relationship to these histories, not just looking at what people of the past made.

“It’s important that people know there is this cultural legacy that is still being passed.”

Dorame’s work has been steadily materializing throughout Los Angeles.

A cosmological installation by the artist was in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial in 2018, and one of her images appeared that same year in the group show “Matriarchs” at ESMoA, the nonprofit art laboratory formerly known as the El Segundo Museum of Art. Currently, she has photography in “Family Album: Dannielle Bowman, Janna Ireland and Contemporary Works From LACMA,” on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s satellite exhibition space at Charles White Elementary School in L.A.

Last year, in collaboration with designer Lilliana Castro, she created a temporary, site-specific installation for Clockshop at Los Angeles State Historic Park. Titled “Pulling the Sun Back — Xa’aa Peshii Nehiino Taamet,” it was broadly inspired by Indigenous architectures and cosmologies and featured an oculus that framed the sun.

But the Huntington photograph, which was acquired by the museum along with another photographic print — “Smoke to Water — Chyaar Paar ‘Apuuchen” from 2013 — is intriguing for the ways in which it is reimagines the institutional context in which it resides.

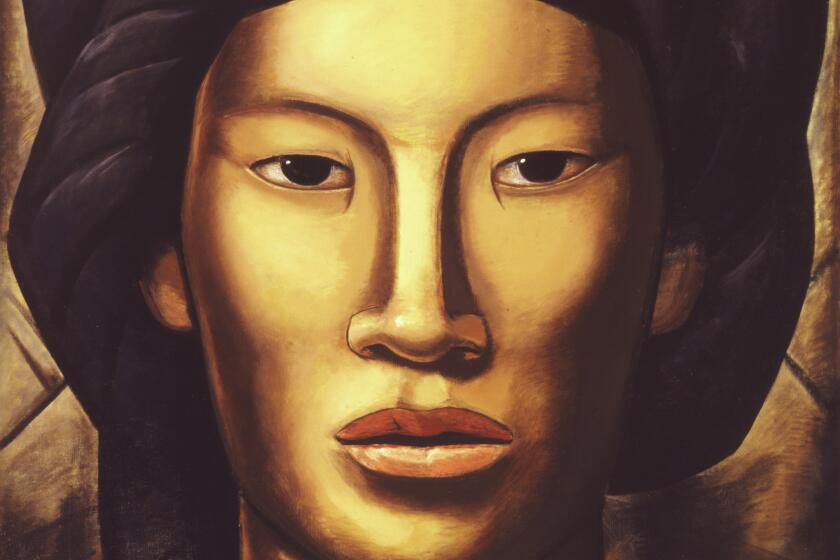

‘Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche’ at the Denver Art Museum reconsiders a foundational figure in Mexican national mythology.

Late last year, the Huntington reopened its American art galleries after their COVID-19 pandemic dormancy with a reinstallation of the permanent collection. “Borderlands,” as it’s titled, seeks to reframe the notion of what gets defined as “American” — especially in Southern California, with its sedimentary layers of Indigenous, Spanish, Mexican and U.S. histories.

Permanent collection installations of American art frequently open with early works by European settlers. Carr sought to upend that. Because the Huntington does not hold Tongva artifacts in its collection, the museum turned to contemporary artists.

In consultation with Los Angeles painter Enrique Martinez Celaya (a Huntington visual arts fellow) and Sandy Rodriguez (a Caltech-Huntington research fellow), the museum’s Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art were reconceived.

The idea, says Carr, was “to begin the story of American art through an Indigenous perspective. And to help our visitors understand the history of the land on which this institution sits.”

How artist Sandy Rodriguez tells today’s fraught immigration story with pre-Columbian painting tools

Riffle through Sandy Rodriguez’s dense rack of painting supplies and you’ll turn up feathers, withered plants and a container of cochineal powder, the fiery red tint produced by the insect that feeds on the leaves of the prickly pear cactus.

As part of this reconceptualization, visitors to the American art galleries are now greeted by works by contemporary artists that explore Indigenous themes. This includes a map painting by Rodriguez that features a wild Los Angeles basin with Indigenous place names, as well as a photographic print by Cara Romero, a citizen of the Chemehuevi tribe, that features an Indigenous girl in the California surf — a work that reimagines the trope of the California girl.

Hanging amid these works is Dorame’s poignant print of the grinding bowl.

The artist’s image, Carr says, “resurfaces histories that are really right in front of our eyes but [that] have not been widely recognized as part of the history of Southern California.”

The historical reframing extends beyond the Huntington’s galleries. Rodriguez is known for working with Indigenous materials that date to the pre-Columbian era, such as vegetable pigments she manufactures herself. In the Huntington’s gardens, she helped revise labels for plants connected to Indigenous knowledge — on each, indicating their Indigenous, Spanish, English and scientific Latinate names. The work even included, says Carr, “planting Indigenous species right in front of the galleries.”

Within the galleries, an education space relates Indigenous knowledge of color and the sources of pigments. “It’s the first time we’ve had an education space in the American galleries,” says Carr. “It helps our visitors think where color came from. Indigenous knowledge and appreciation of color is so profound.”

Father Serra Park in downtown Los Angeles will be renamed in consultation with Native American tribes.

That Dorame’s work features so prominently in an important art collection is unexpected, since she didn’t set out to be an artist.

Early on in her studies at Santa Monica College and later at UCLA, she thought she might become a photojournalist. But she found the pursuit constricting. “I had a hard time with all the rules around it,” she says. So she ended up completing an undergraduate degree in English literature instead.

For a time, she set the camera aside completely. But a fortuitous pit stop during a cross-country road trip after graduation reconnected her with the medium. Dorame was driving to New York and stopped to visit family in New Mexico. Her uncle gave her an old medium-format Rolleiflex camera — the sort that requires the photographer to peer down into the viewfinder rather than hoist the camera up to her face.

“It’s all manual. There is nothing automatic,” she says. “The pace completely changes. And I realized that’s what I liked.”

Seven years after graduating from UCLA, she received her master’s in fine arts at the San Francisco Art Institute. To this day, the medium-format film camera remains her tool of choice (although she now uses a Hasselblad).

Enrique Martínez Celaya is simultaneously staging exhibitions at USC, the Huntington, and UTA Artist Space — each of which provide a different glimpse into his provocative, thoughtful approach to art.

Dorame’s interest in art and photography intersected with a role she has occupied since she was 18: serving as a cultural consultant around the Los Angeles area when Indigenous artifacts and remains are unearthed during construction. It’s a role her father has long occupied and one in which he began to include her when she became an adult. (One of the most prominent cases Robert Dorame has worked on is that of an Indigenous burial site unearthed when a luxury housing development was being built in Playa Vista in the early 2000s — an event that triggered a five-year legal struggle over how to adequately re-inter the remains.)

“It’s super important,” Mercedes Dorame says of the role. “But you don’t have any power.

“My dad always said the job was to remind people of the humanity. That this is someone’s uncle or grandmother or child. Because of the history of Native people in museums — collected or displayed — you’re so objectified. ... It’s not even human to people. So he said to me, ‘Your job is to remind people of the human-ness of these remains, of these belongings.’”

This has led her to create work that bears witness to the Tongva experience. This includes highlighting the knowledge of the past — be it stories, tools or cosmography. “My ancestors were technologically advanced,” she says. “They could get to the Channel Islands in a ti’at — a wood-plank canoe — while using systems of navigation. Not a lot of people could do that. It’s quite sophisticated.”

But her work also includes articulating a contemporary presence — an affirmation that Indigenous people do not exist only in history books as some prequel to European colonization. And to do it in a way that rests lightly on the land.

“If you think about the land artists who are making these deep, permanent incisions, this statement of ‘I am here,’” Dorame says. “I want to think about what it means to make work on the land.”

The art, perhaps, doesn’t need to be permanently borne by the landscape. Perhaps the frame a photograph can put on it is enough.

“When I use the camera and take images, it’s this permanent record, and I’m able to control what the viewer sees,” Dorame says. “So much of the control of Native imagery was taken away from Native people. For me, it’s a reclaiming of that language.”

And for the rest of us, a spotlight on the Los Angeles that resides quite literally beneath our feet but that we often fail to see.

‘Borderlands’

Where: Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 1151 Oxford Road, San Marino

When: Closed Tuesdays. Reservations required on weekends

Admission: $13-$29; children younger than 4 are free

Info: (626) 405-2100, www.huntington.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.