“Things have been so scary lately with Russia,” states TikTok user @MojoX with dead earnestness in a post from early March, “that I went out and got myself a Gen X bomb shelter.”

Cut to a photograph of a school desk — an image that evokes, for generations of Americans through Gen Xers (of which I am one), memories of those farcical drills in which we prepared for inevitable nuclear annihilation at the hands of the Soviets by stuffing ourselves under our desks.

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine passed the month mark, and reports emerge that Russia’s nuclear forces have been placed on high alert, the culture of the late Cold War has made a swinging comeback. Think of it as Cultural Cold War 2.0, with Russia as stand-in for the former Soviet Union.

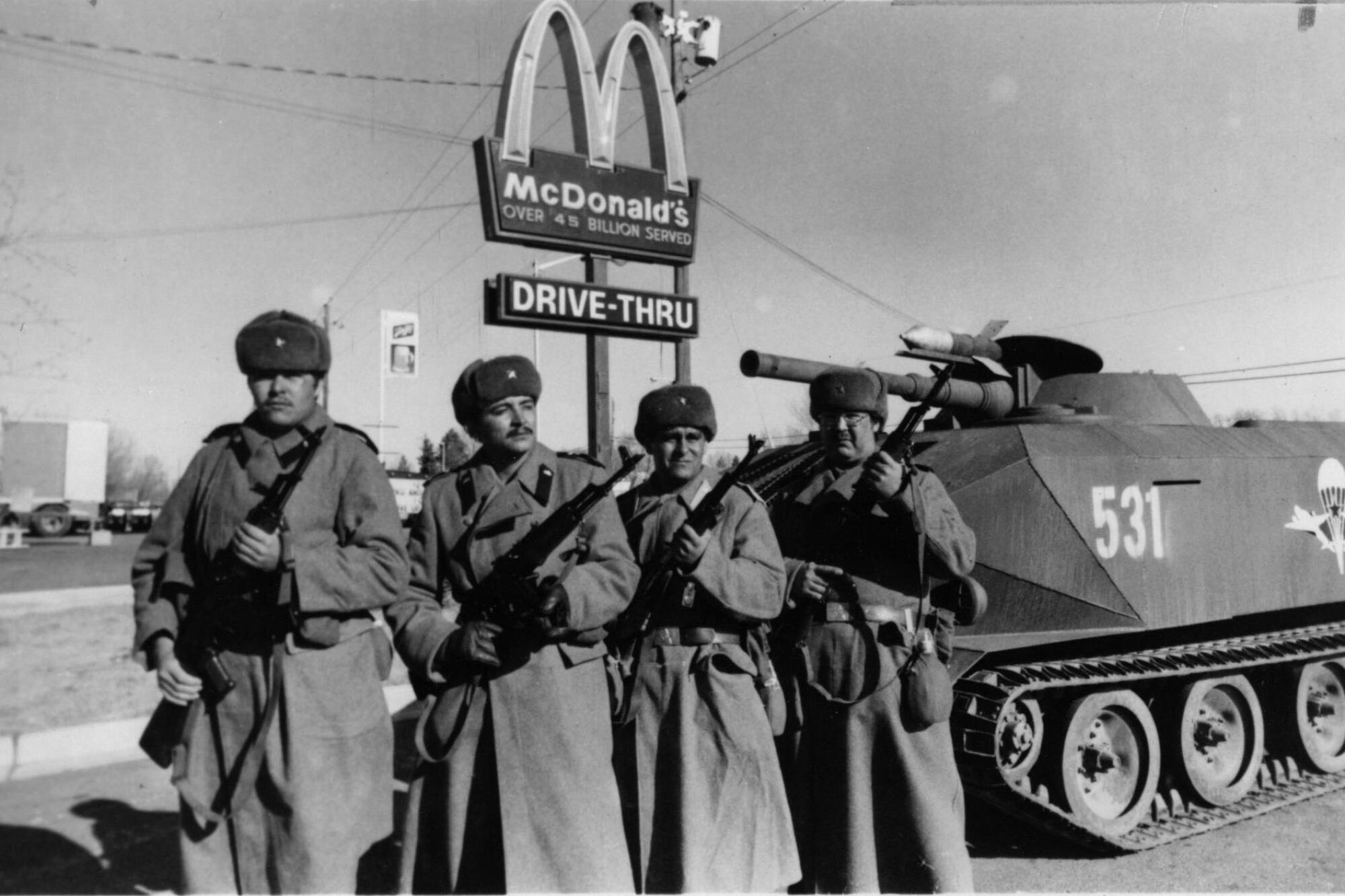

“Red Dawn,” the 1984 Patrick Swayze/Charlie Sheen/Jennifer Grey movie about a group of high school kids from small-town Colorado who fight off a Soviet land invasion with a few hunting rifles and can-do gumption, saw a surge in popularity on streaming services in the wake of the Russian invasion. Also enjoying a post-invasion boom is 1985’s “Rocky IV,” from Sylvester Stallone’s boxing franchise, in which the all-Italian-American hero fights off a machine-like Soviet aggressor, Ivan Drago, played by Swedish actor Dolph Lundgren in mean-mug mode.

References to these films have also materialized on TikTok in the wake of the invasion. “Don’t worry folks. Gen X has been prepared for this since we were kids,” goes one such post in tribute to “Red Dawn,” followed by the obligatory “WOLVERINES!” in all caps — a reference to the high school mascot that also serves as the battle cry for these high school guerrillas, who not only fight off the Soviets but also their pumped-up Nicaraguan allies. (“Red Dawn” is peak Reagan-era absurd.)

Also prominent are references to the 1983 made-for-TV movie “The Day After,” in which Jason Robards played a kindly doctor in Lawrence, Kan., struggling with the devastation wrought by a Soviet nuclear attack. The film, when it first aired on ABC, was a cultural event — drawing an unimaginably massive audience of 100 million people (at a time when the U.S. population was about 236 million) and terrorizing a generation of viewers with its scenes of abject devastation. When I was in junior high, we took an entire period out of social studies class to discuss it in earnest.

In the days following the Ukraine invasion, TikTok user @Vampslayin posted a vintage news report about the film’s social impact: “Who remembers watching this as a kid?”

“I do,” responds @chefmichelleagnew. “It was and is still frightening.”

“I was going to show some video,” says @diva_dee25 of the film in a post about the movie, “but then I realized, when I watched the videos again, it kind of retraumatized me because I felt like I was back on that day when I first watched that movie.”

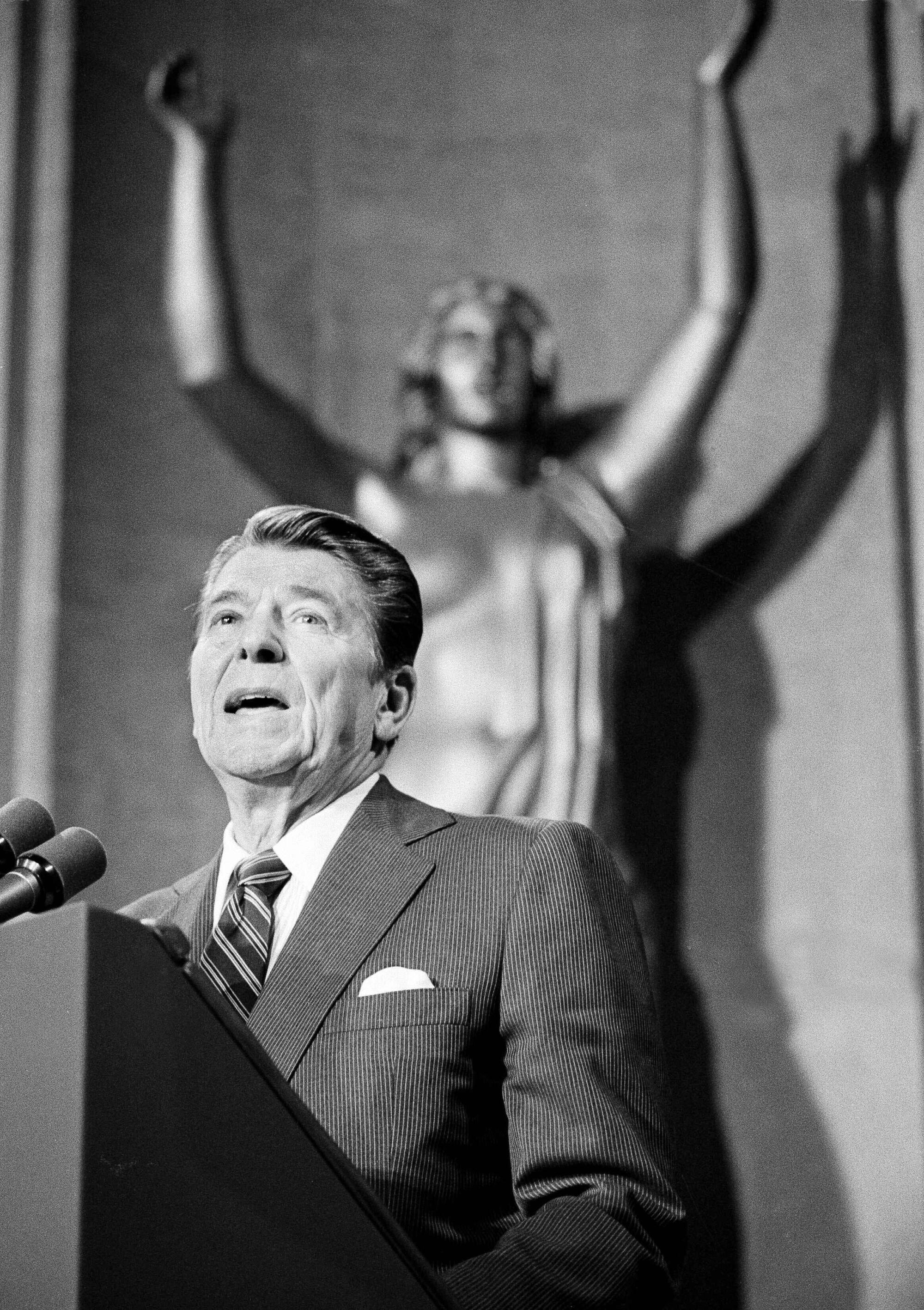

I was indeed rendered sleepless by “The Day After.” As NPR’s Neda Ulaby, who grew up in Lawrence and was around for the filming, noted in a report marking the film’s 20th anniversary, “The Day After” landed amid some intense Cold War bellicosity and anti-Soviet paranoia. The year in which it was released, President Ronald Reagan branded the Soviet Union an “evil empire,” and the Soviets shot down a Korean commercial airliner that had accidentally veered into their airspace.

On the radio, songs such as “99 Luftballons,” by the German synth-pop band Nena, imagined a devastating war triggered by the innocent release of a few helium balloons into the air. The song appears as the soundtrack to another gag on TikTok that shows an image of a school desk emblazoned with the phrase: “I bought a Gen-X bomb shelter today.”

Regardless of how Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine ends, it marks a turning point in history: a return to hostility between Russia and its neighbors.

In retrospect, “The Day After” is hokey. The film pummels its audience with an hour of heartfelt backstory before getting to the main event. When the nukes finally do arrive, the devastating effects of the bombs on people are rendered by showing outlines of their skeletons, as if they were cartoons.

If you want to experience some late Cold War dread, I recommend “Threads,” a British nuclear annihilation film that aired on the BBC in 1984. Combining elements of faux documentary and feature filmmaking, the movie tracks the lives (and grim deaths) of several individuals inhabiting the English city of Sheffield over the days, months and years following a nuclear attack. Starkly filmed — at times juxtaposing still images against the clinical delivery of unseen newscasters — it evokes elements of French director Chris Marker’s stylish and devastating “La Jetée.”

As with other late Cold War culture, “Threads” has also surfaced on TikTok.

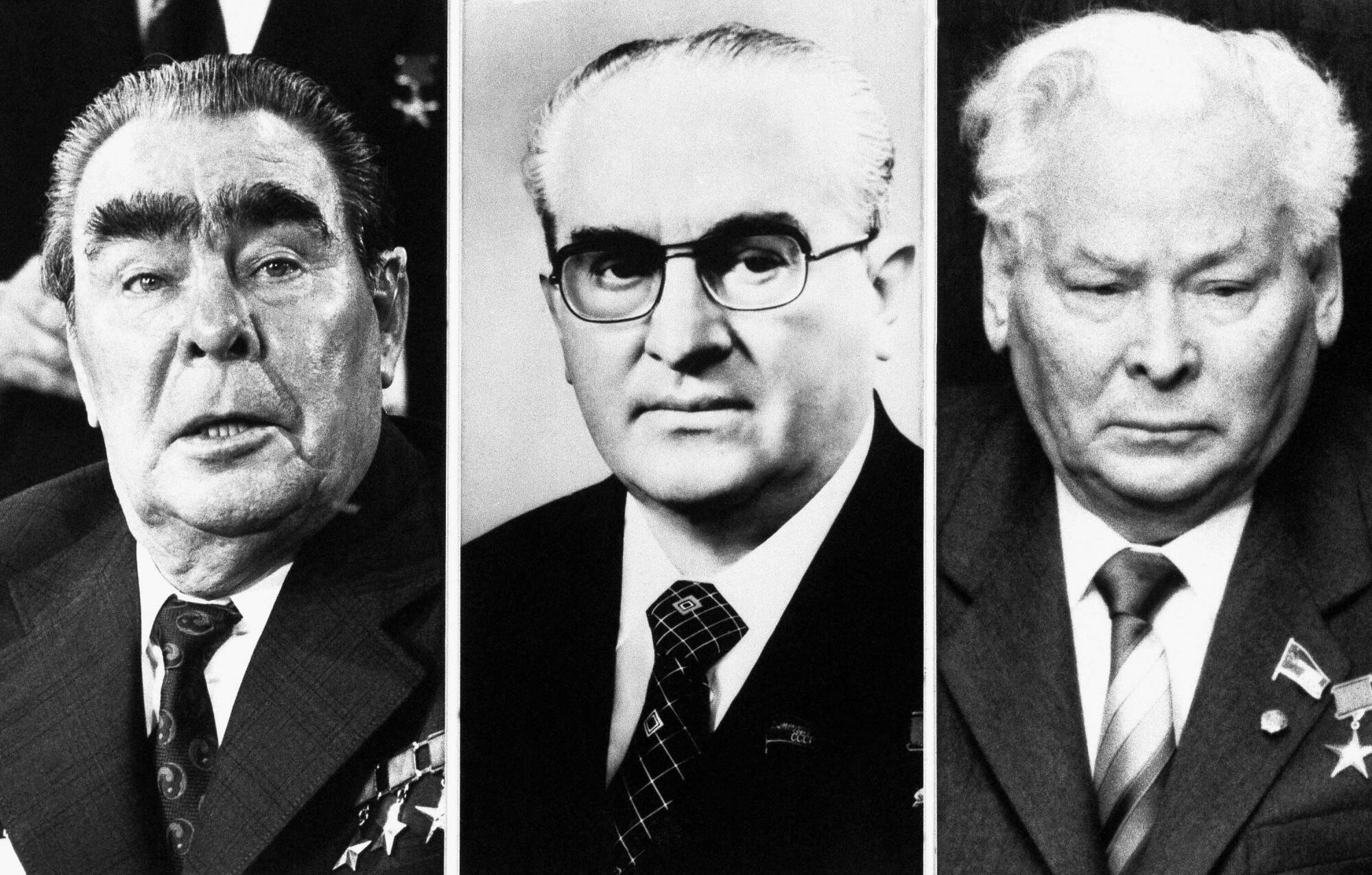

These cultural artifacts, along with the Ukrainian war itself, are now grist for the meme mill, often presented online through the lens of Gen X, the generation born between 1965 and 1980. A video posted to TikTok by @Kristanistan ascribes the disparities in leadership styles between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to generational differences.

Putin (born 1952) is the boomer: “He’s a gaslighting authoritarian who has zero economic policies,” goes the narration. “He’s outdated.”

Cut to images of Zelensky (born 1978) in his trademark olive garb, urging the citizens of Ukraine to take up arms against an invasion. “Then you’ve got this badass Gen Xer,” continues the narrator, “who is sick of this boomer s—.”

“Perhaps this is a plea,” the video concludes, “for old leadership to pass the reins to new leadership.”

Many social media posts describe Gen Xers as somehow uniquely suited to the Cold War 2.0 moment. Now uncomfortably middle-aged (I’m 50), we’ve been through the bomb drills, seen the anxiety-inducing movies and have events such as the “Miracle on Ice” occupying space in our brains. (That’d be the time, in 1980, when the U.S. hockey team unexpectedly beat the Soviets 4-3 at the Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, N.Y.)

What sets us apart from U.S. baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964), who also lived through the Cold War, is that, as a generation, we were too young to have a political hand in it. (I was 18 when the Berlin Wall fell.) Instead, in the U.S. at least, much of our memory consists of observing it helplessly from the sidelines while hoping that a delusional hawk with access to the button wouldn’t be the death of us all.

“This is why Gen X is taking this in stride,” reads the caption on a post by TikTok user @shelc21 as she listens to Alphaville’s “Forever Young” — another popular German synth-pop tune about the anxieties of living in a nuclear world. Sample lyrics: “Hoping for the best, but expecting the worst / Are you gonna drop the bomb or not?”

It was a song I slow-danced to in junior high.

The backdrop to some of Zelensky’s most urgent social media videos is an unusual piece of Kyiv architecture created by “a man who hated the dull, the safe, the easy.”

In one recent TikTok video, a millennial freaks out over the invasion: “I’m so f— tired of living through major historical events!” he rants. Meanwhile, in a reaction post, a Gen Xer who goes by the handle @thatcrazyaunt watches him, nonplussed, as she grabs a glass of orange juice. A caption materializes below her: “Don’t have a cow man. That’s the behavior that starts those historical events.”

In a tweet posted in late February (which has since circulated on TikTok), comedian Jay Black offered the following advice for millennials and zoomers dealing with their “first bout of World War III panic.” As he writes: “Find yourself a Gen X friend to see you through it.”

The idea that Gen Xers, my relentlessly scrutinized slacker generation, would come into their own amid Cold War 2.0 is morbidly amusing. As is the idea that a bunch of olds who watched “The Day After” on TV are somehow prepared to meet the moment — psychologically or otherwise. (The birth of Generation X, after all, largely coincides with the conversion of the military to an all-volunteer force in the U.S. in 1973, so I can’t speak for how well most of my generation would fare in an actual war.)

Generational divisions are always facile at best. (Syrian dictator Bashar Assad, after all, who was born in 1965, is technically a Gen Xer.) But collectively, the wave of social media posts marks a moment of history and culture circling in on itself into a familiar darkness of bloody proxy wars and grinding uncertainty. And as we know from the last time, hiding under our desks — well, it won’t save us from anything.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.