Commentary: I’m still hyper-vigilant about COVID. Why do I feel so alone?

California recorded a million new cases of COVID last week, hospitals are overtaxed, and it feels like everybody has Omicron — or knows somebody who does — as sickness, ennui and burnout already are defining the new year. Could this last part explain why the current pandemic peak is being met with a collective shrug?

As an arts writer who has seen theaters and concert halls go dark for the better part of two years, in the name of public safety, but now is watching those same venues boldly open their doors to what many people are referring to as “the new normal,” I am flummoxed. With caseloads breaking records and death counts rising once again, why now? I want to share in the optimism but I can’t. In fact, I feel as if I’m being gaslighted.

For the first two years of the pandemic, “Don’t get sick” was the constant refrain. But now popular sentiment has shifted to some version of “It’s fine if you get sick, because if you’re boosted and vaccinated, symptoms will probably be mild. Better to just get it over with.”

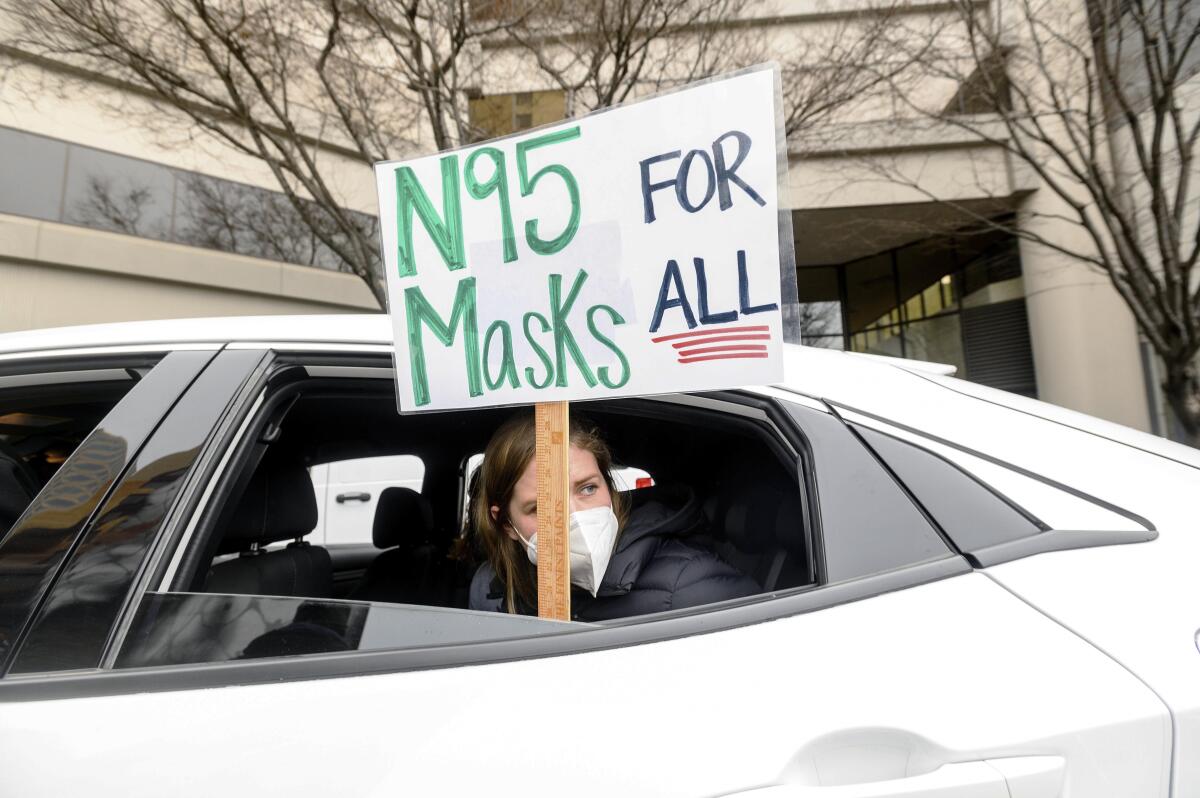

In this climate it’s easy to feel foolish if you choose to remain extra vigilant — as though everything you’ve come to believe about the virus is so much dramatic hand-wringing. When you walk by a gaggle of people at a crowded bar in your N95 mask, you see a collective look that says, “Lighten up.” Scrolling through social media can make you feel as if you’ve invented the pandemic from whole cloth.

Art fairs are logistically complicated events in the best of times. Why the LA Art Show, Frieze Los Angeles and others say the show must go on amidst the pandemic.

This is a vast oversimplification, but to my mind there are three basic tribes when it comes to pandemic caution. The first two are abundant: the paradoxical my-body-my-choice anti-vaxxers and anti-maskers, who have flouted basic health and safety precautions throughout the crisis; and the middle-of-the-road COVID believers who have masked up when necessary, dutifully gotten their vaccines and sometimes their boosters — but who also have been keen to reclaim their lives and to exercise situational flexibility to achieve a semblance of normalcy.

The third tribe, to which I claim membership, is what my father wryly calls “the COVID nuts.” I’m not thrilled with this moniker, but I’m a big girl with a droll sense of humor, so I’ll take it. Especially if people like me can be granted a bit of grace and understanding during this difficult and confusing time.

COVID nuts may have wiped down their groceries and let their mail mellow for a bit longer than the rest of you. But for the most part we try to fit in. The hallmark trait of a COVID nut is extreme caution. We are highly risk-averse, and we tend to believe deeply in the value of collective action and the power of communities working together to rein in the ravages of the pandemic. We threw ourselves behind the early pandemic rallying cry, “We’re all in this together!” and never quite stopped.

I have felt unfairly judged by certain op-eds that have come out post-vaccines, claiming that folks still wearing masks were doing so for reasons of blatant political partisanship. The insinuation — that continued COVID caution was a reverse “owning the libs” move aimed at agitating the far right — rankled me. For some of us, masks kept our hypochondria and extreme anxiety at bay.

It’s painful to recall the earliest days of the pandemic, when we didn’t know much about how the virus spread, and it felt like it could be everywhere and anywhere at all times. Plenty of youngish people like me were dying.

My daughters were 3 and 11 when the nightmare started, and the fear of not seeing them grow up left me in tears. I began checking in on my parents multiple times a day. If I didn’t hear back from them, my stomach would clench with worry and my palms would sweat. I couldn’t eat. I lost weight. Laughter did not come easily.

Until my family was vaccinated, we made life in a bubble work. My husband and I had the extreme privilege of working from home, and we were lucky to have a big backyard for our kids to play in, and for the occasional socially distanced visit.

Most people we knew were basically on the same page, but fractures began to appear post-vaccine. I still wasn’t completely comfortable letting my guard down. My younger daughter was not yet authorized to be vaccinated, and I fell into the extra-cautious-parent camp — still distancing and masking to reduce her risk. I told myself that when she finally got a shot, our family would make our grand entrance on the new world stage.

“Just a few months more” became my mantra as life in the pandemic dragged uncomfortably on — like the “Sex and the City” reboot.

My younger daughter was fully vaccinated the day after Thanksgiving — just in time for the Omicron surge. So the masks stayed on. The social circle remained minuscule. The sanitizer and rapid tests, abundant.

Too many vulnerable people are out there — the elderly, unvaccinated babies and toddlers, the immunocompromised, frontline and essential workers — to center only ourselves and what we anticipate will be a variant with mild symptoms. And while I do believe the virus is on its way to becoming endemic, it’s certainly not there yet, and likely won’t be until it has killed nearly 1 million Americans, maybe more. To give up the fight now, to let my guard down, seems like folly. Yet that is exactly what I’m being asked to do in the pandemic twilight of Omicron.

Omicron is being felt by the film and TV industry, as Hollywood productions delay the restart to work in the new year.

In some ways, the thought of succumbing to the virus sounds relieving —to open the door and let the boogeyman in. From what I’ve heard via many friends and family members who have come down with Omicron in the past month, it’s really not that scary after all.

But the thing is, I remember.

I remember the quavering fear in a young dancer’s voice when I interviewed her about the Metropolitan Opera closing down in March 2020. How she cried over the phone from her apartment in New York City when she began talking about holing up inside with her partner and small children as ambulance sirens wailed day and night and the hospital down the street erected a makeshift morgue.

I remember the traumatized family members I interviewed for a series of pandemic obituaries — the agony they expressed over their loved ones dying alone. The adult daughter who told me her father had just gone to the bank, then he got sick. And then he died. She recalled how she used to try to safeguard his health by monitoring the desserts he ate at family dinners. How he’d still manage to steal a cookie, and how it always made her laugh. How lost she sounded as she told that story.

I remember the shock and awe I felt when I received word that the Hollywood Bowl would go dark for the entire summer — the first time in its nearly 100-year history. A history that included the Great Depression and two world wars. The quiet numbness in the voices of the executives I interviewed. The implications — lost ticket revenue, lost jobs, lost sense of community and togetherness — that stretched as wide as the valley beyond the famous venue. The sickening feeling that we were in this disaster for much longer than we had anticipated.

I remember booking Zoom tours of kindergartens when my daughter turned 5. I remember taking her to the closed campus of a school that we thought she might like — how she peered at the empty playground through a chain-link fence, how we wiped dust off a window to look at barren hallways. The weeds in the schoolyards, the trash collecting in the breeze at the curb.

I remember these things happened. And I know they could happen again. What Greek letter comes after Omicron?

“Just a few more months,” I tell myself.

When hospitals aren’t overwhelmed, when sickness is not at crisis level, when I can be sure my parents will be OK if they are infected. Maybe then I’ll toss my mask and join the ebullient crowd.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.