Remembering John Madden, the video game character

Football wasn’t the sport I gravitated toward as a kid. But John Madden certainly made the argument that it should be.

Madden, the coach and broadcaster who died Tuesday at age 85, is the reason I even understand the game. Well, to be perfectly accurate, the credit should go to the video games that presented his larger-than-life persona and his gregarious perspective toward the sport. But I always associated the approachability of the “Madden NFL” series, especially in its late 1980s beginnings and its mid-’90s stride, with the coach.

Today, the yearly “Madden” iterations, depending on how one opts to play, can be complex simulations that emphasize the modern, star-driven game. New releases zero in on tweaks that make the video game more realistic, such as refinements to tackling techniques that even account for the weights of individual players. But they’ll also contain game-changing power-ups that treat NFL players like superheroes.

These aren’t contradictions. They’ve always struck me as the continuation of a franchise associated with an impossible-to-ignore personality, a tone passed down from someone who loved the game in all its splendor, strategy and silliness.

Today, it’s common for video games to boast celebrities and lifelike re-creations of athletes. Then, Madden was one of the first to lend his name, voice and persona to the medium, a stroke of marketing genius that turned the football legend into a vital piece of video game intellectual property. It all worked so well because the early games, in which players could practically soar across the field for a few extra yards, felt like a love letter to football while gracing the name of someone who adored it probably more than anyone.

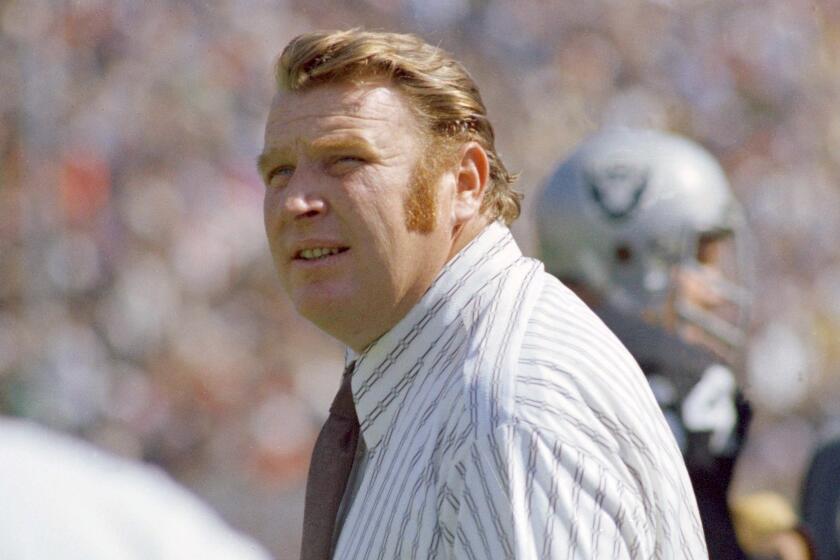

NFL star John Madden, who reached the top of his profession in coaching, announcing and video games, died unexpectedly Tuesday morning at age 85.

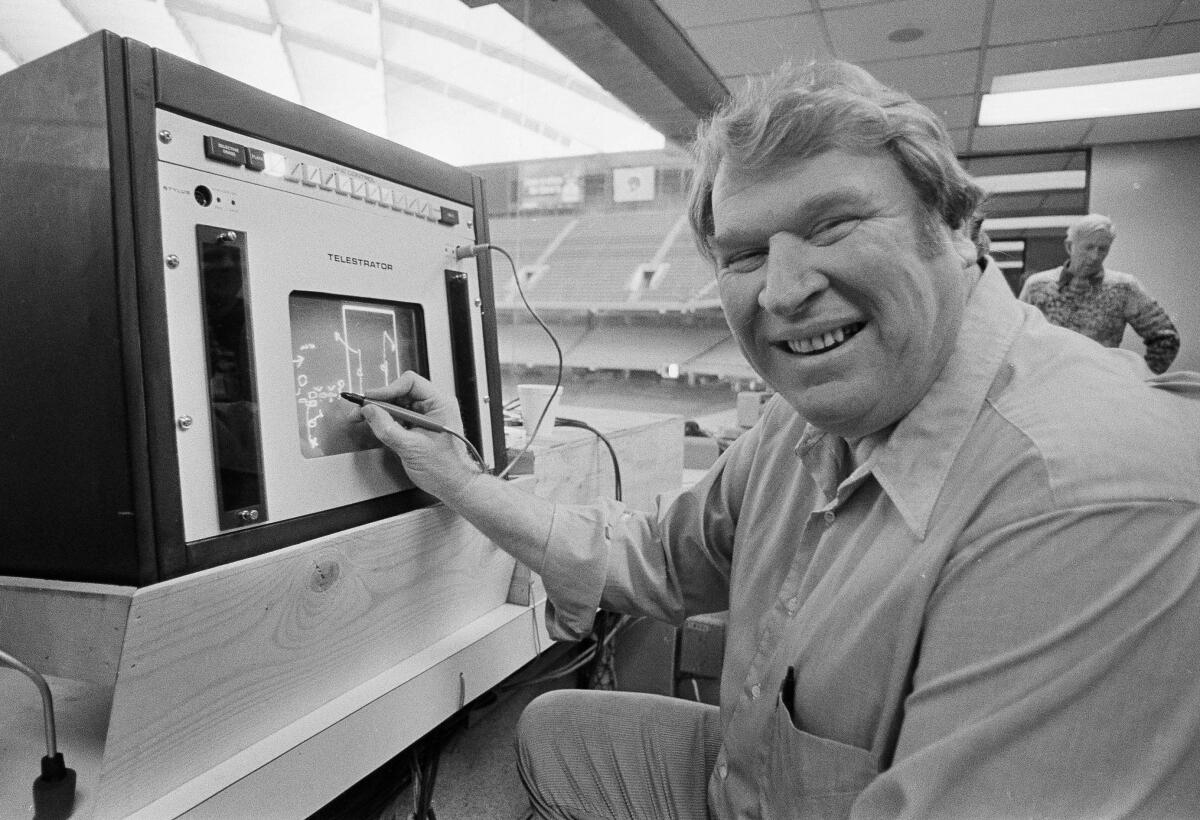

Natural fidelity was always the goal, of course, the latter a moving target based on technological limitations. And over the decades, the video game has influenced NFL broadcasts and their digital overlays. As our world has gotten more digital, video game makeovers are noticeable practically everywhere, and the lines, circles, skids of the “Madden” games today dominate almost every sport’s televised presentation. Circa 2022, the NFL looks more like a video game, and the video game inspired by it feels more true than ever.

But while today’s “Madden” games may not have the instant pick-up-and-play approach of the early years, they still present a digitization of the sport that makes it seem far more welcoming and congenial than practically anything we see or hear on Sundays. See the addition of this year’s feature called “Gameplay Momentum,” an arcade-like meter that aims to capture all the intangibles when a game involves actual humans.

It’s kind of a “luck” feature. But it’s also the sort of stuff that NFL broadcasters talk about and normalize and a realization that as much as we interact with a game, we’re also watching our decisions unfold. That’s an important distinction, because while Michael Jordan and Larry Bird would also lend their names to video games around the time the “Madden NFL” series was taking flight, we don’t ever see ourselves as superstar athletes. We are coaches and broadcasters — those directing and commenting on the action more than making it happen.

Madden wasn’t a gamer, but he knew this.

“I’m not very good,” he once told The Times. “I don’t play well enough to really test the game for a gamer. But I have games all over. I have games at home, games here in the office, games on my bus. I get more out of watching other people play, and then where I can watch a game like I’m watching on television.”

Although the games no longer use Madden’s commentary, they still posses a boisterous enthusiasm that can be traced to his broadcast style. Adult me appreciates that sort of liveliness in the modern games. Young me, however, found that tone to be something of a tutor. Again, by design.

“That’s one thing pro football has to watch out for — they’re not getting young kids,” Madden told The Times in 2002.

“If you get a kid, say between 8 and 15, he’ll be more of a video game fan than a fan of football,” Madden said. “It used to be that kids learned about football by playing it in the park or in their backyard. Now kids learn about it by playing the video game.”

That only worked because the game strove to make NFL playbooks understandable. Madden’s involvement in the game can be traced to a mid-’80s train ride, when then-Electronic Arts President Trip Hawkins, one of the game’s key architects, met with the football legend on a rail jaunt from Denver to Oakland.

To agree to be involved, Madden had requests. A USA Today article from 1989 runs down some of the key philosophies the coach wanted to bring to the game: “the paramount importance of matchups and field conditions, the caveat to avoid trick plays, and the wisdom of trusting the percentages.”

NFL legend John Madden was more than a star coach, broadcaster and video-game innovator. He was a funny, generous friend to everyone he met.

In the late ’80s, I would watch my dad and my cousins play a relatively rudimentary football game — “NFL Challenge” — at Christmas Eve gatherings, its Xs and O’s a world I didn’t understand. But it was a grown-up universe that looked appealing, one full of sarcastic jokes and camaraderie, dialogue that if I could remember any of it would probably make me or my mother cringe today.

The “Madden NFL” games provided a bridge to this world, allowing us to draw our own plays — never as good as those endorsed by the in-game Madden, of course — to see how a game of football would unfold. To understand, in other words, how those Xs and O’s transformed into people. But the games also understood that football needed its edges softened if its appeal would be forever widened.

As Hawkins told USA Today of that initial train ride: “Madden spent the whole day chewing on a huge cigar that must have been about a foot long. He never lit it, and by the end of the day it was pretty disgusting,” Hawkins recalled. “Madden is a real no-nonsense kind of guy, consistent and credible. In the TV ads, he’s almost like a cartoon character; he’s playing the character of John Madden. In fact, he’s not like that at all.”

The Madden I know is that cartoon character, to football what Mario and Luigi are to New York plumbers.

But that doesn’t make any one of them any less real. Every game or narrative is more relatable with an approachable personality at its core, and with one of the loudest and most jovial at its center, the “Madden NFL” franchise is now as material as the NFL itself.

‘Sable,’ ‘The Artful Escape,’ ‘Unpacking’ and more of 2021’s best games asked questions about our place in the world and how we define our lives.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.