Smell and sound: Artist Florian Hecker turns a historic Schindler home into a sensory experience

It is easy to describe a scent. For example, LAX in the 1970s smelled like jet fuel and stale cigarettes.

But how to describe the act of smelling? Does the jet fuel land sharply on your nostrils, or does it inundate the senses like a rising tide? Does the scent of a lit cigarette evoke earthy pungence or sickly vapor? Do the combined smells churn the stomach or trigger nostalgia for journeys taken long ago?

In case you are not among her several thousand followers on social media, Susan Orlean has been teaching herself kintsugi, the ancient Japanese art of mending broken pottery with gold.

A thousand people could give a thousand different answers since smell doesn’t lie in a scent’s source, but in the intensely personal archive of experience and sensation the smeller brings to the act.

This sensory space — between an object and its perception — is an area of interest to German-born artist Florian Hecker, who once created a book-length work inspired by the nature of timbre, the difficult-to-define resonances that allow the human ear to distinguish one sound from the next. A high C may be a high C, for example, but timbre is part of why a high C sung by Maria Callas might land on the ear differently from one sung by Kathleen Battle.

Hecker currently has an installation on smell and sound at Rudolph Schindler’s historic Fitzpatrick-Leland House in the Hollywood Hills. The show was organized by Ellie Lee and Matt Connolly of Equitable Vitrines, a roving arts nonprofit, with the assistance of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, which supplied the location.

“Resynthesizers” dwells on the aforementioned vagaries of perception. It also goes down intellectual rabbit holes related to synthesis, the history of fragrance chemistry and the nature of the space.

And what a space it is: Schindler’s 1936 structure consists of several interlocking geometric forms that cling to the crest of a hillside and frame views of Laurel Canyon.

Hecker does little to intervene in the Fitzpatrick-Leland House — at least visually. (While the work acknowledges the house, it was not directly inspired by it; some of these ideas are ones that Hecker has been exploring for decades.)

Spread out around the two-bedroom home, which occupies three levels on the side of the hill, viewers will find three industrial diffusers, three speaker stacks and three small electrophoretic displays (a.k.a. e-ink displays) — all of which come together to dispense bursts of scent, sound and text as you amble around.

An Apple store redo of Tower Theatre and the renovated William Randolph Hearst Herald Examiner building bring Broadway’s historic architecture back from the brink.

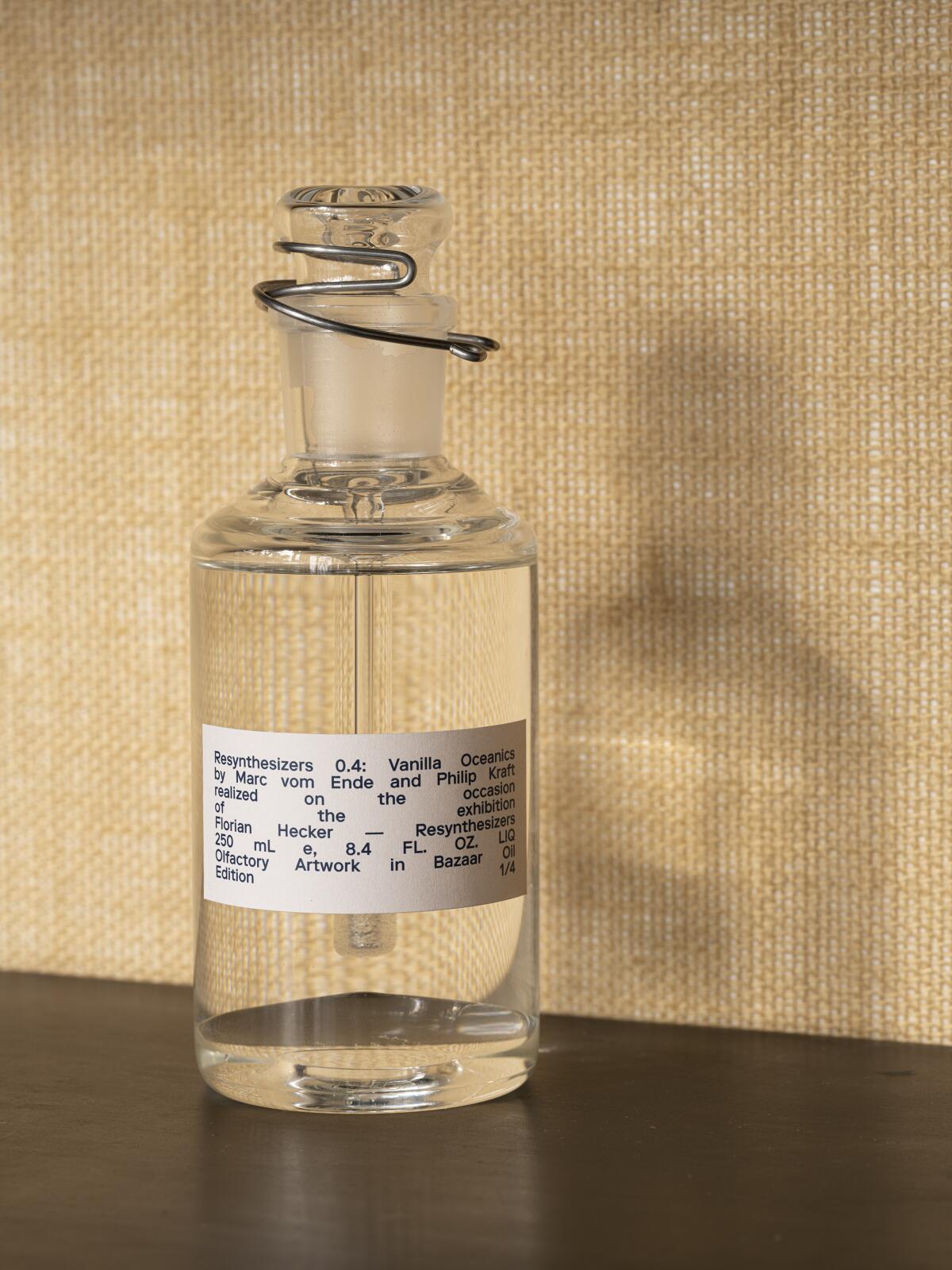

The three scents chosen for the project — all synthetic — each have a historical significance. The first, vanillin, is a synthetic vanilla extract devised by German scientists in the 19th century that became an important ingredient in what is widely regarded as the first modern perfume: Guerlain’s Jicky. Two other diffusers dispense Calone, a popular perfume ingredient devised in 1951 that evokes marine qualities with undertones of melon (think commercial “ocean breeze” products), and Flowerpool, an antiseptic scent that was trademarked this year — and is a smell truly worthy of a pandemic.

Like the scents, Hecker’s sound component is also a product of synthesis, the fusion of different elements into a different whole.

In fact, the artist, who now divides his time between Portugal and Germany, is known primarily for his sound work. In 2016, he produced an experimental binaural sound piece titled “Inspection” for the BBC that featured synthetic sounds and machine-read texts. And for years he has worked with Axel Roebel of Ircam, a Paris institute devoted to the study of music and sound, to produce computer-generated sounds that are then synthesized and resynthesized to create new sounds in the process. For the purpose of his L.A. installation, Hecker has arranged it so that these sounds rotate, in sequence, throughout the sets of speakers staggered around the house.

Accompanying scent and sound are the streams of text that materialize on the e-ink displays, which are presented like minimalist sculpture, leaning against walls. The text is a libretto by British philosopher Robin Mackay that brings together — one could say, synthesizes — texts about fragrance chemistry, synthetic sound, the architecture of the house and even the libretto itself. It also refers to elements of some of Hecker’s previous works.

Sample passage:

CALIFORNIATED EUPHORIA

OF RETURNING HOME

TO THE GREAT OUTDOORS

A CITY EVERTED

UNASSIGNABLE PARTS

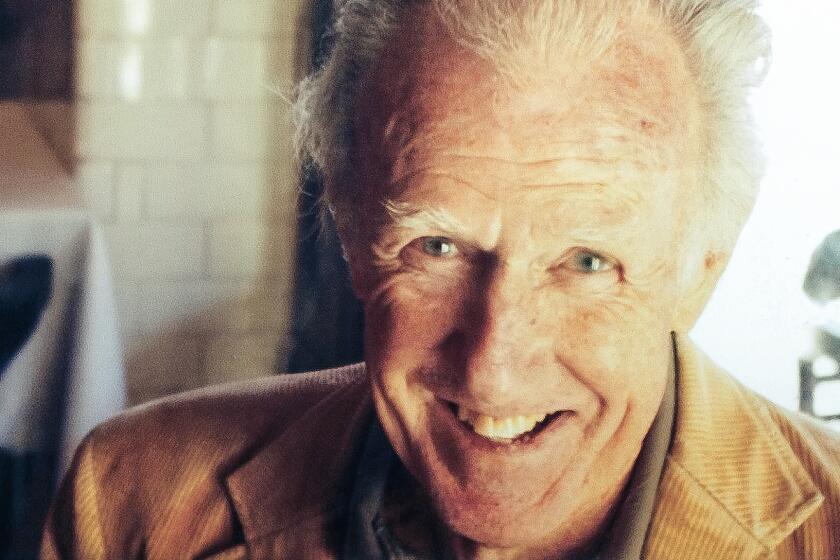

Eclectic designer Bernard Judge, who helped preserve the historic Schindler House and built South Pacific lodging for Marlon Brando, dies at 90.

“Resynthesizers” is like a Russian nesting doll of thought experiments — a synthesis of syntheses — one that is partly explained by a dense handout flyer printed in tiny sans-serif font.

The piece is also quite the cacophony.

Around the stairwell, where the rooms intersect, the scents come together to form a weird amalgam — the sort of smell one might imagine if the Yankee Candle Co., purveyor of sickly sweet scented candles, suddenly began manufacturing hospital cleaning supplies. At moments, it all comes together in a scent that evokes industrial plastics; at others, it’s a nightmare vanilla potpourri. But linger in the individual rooms themselves, and some of the individual scents come into sharper relief.

I particularly enjoyed Calone, diffused in the bedroom areas, which mingled with the breezes that penetrated the house. Was that the Calone? Or was it the actual breeze? The exact borders of any given scent can be impossible to define. But, in combination with Schindler’s architecture, the scent felt clean and comforting. It also felt familiar. That’s probably because Calone is employed as an ingredient in a vast array of colognes and perfumes, including scents by Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein and Christian Dior.

I had a similar experience with the sound elements, which for long stretches sounded simply like noise. At moments, however, I felt like I could make out recognizable contours through all the computer-generated racket: sounds that evoked the spray of water, a broken music box, the static of a vintage TV set in the days in which channels reverted to grainy fuzz after midnight.

At least, that’s what I heard. The thing about smelling and hearing is that our mind looks for patterns and fills in the rest. The sound of a broken music box to my ears could be a crashing piano to someone else.

Hecker’s art, therefore, doesn’t take place within the rooms of the house so much as within the synapses where we attempt to process the world around us. As I left the installation, Mackay’s textual display flashed on the screen at my feet:

THIS IS AN INTERNAL DRAMA

STITCHED INTO OTHER SPACES

It’s an astute observation. The piece is all internal: inside of you and inside of itself.

Each visitor to “Resynthesizers” gets to take home a package of scent sticks based on the scents employed by Hecker in the installation. Separately, they smell like sugary vanilla, clean breezes and pungent antiseptics — and, when I put them all together, they take me back to my hazy afternoon at the Fitzpatrick-Leland House. And that is a place that is always worth revisiting.

Florian Hecker: 'Resynthesizers'

Where: Fitzpatrick-Leland House, 8078 Woodrow Wilson Drive, Los Angeles

When: Through March 13, 2022

Admission: Admission is free, but advance reservations are required.

Info: equitablevitrines.com and makcenter.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.